Ptolemy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ptolemy

|

|

|---|---|

| Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαῖος | |

Portrait of Ptolemy by Justus van Gent and Pedro Berruguete (1476)

|

|

| Born | c. AD 100 Unknown

|

| Died | 160s/170s Alexandria, Egypt, Roman Empire

|

| Citizenship | possibly Roman |

| Known for |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

Claudius Ptolemy, often just called Ptolemy, was a brilliant ancient Greek-Roman scholar. He lived around 100 to 170 AD. He was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer, and even a music expert! Ptolemy wrote many important books. Three of his most famous works shaped science for over a thousand years.

His first major book was about astronomy, called the Almagest. It was like a huge textbook explaining how the universe worked. His second big work was the Geography. This book taught people how to make maps and described the world as it was known back then. The third important book was the Tetrabiblos. In this, Ptolemy explored how the stars and planets might influence life on Earth, trying to explain it using the science of his time.

Ptolemy's ideas, especially his model of the universe with Earth at the center, were widely accepted for a very long time. Even though his models were complex, they helped people understand and predict the movements of celestial bodies for centuries.

Contents

Who Was Ptolemy?

Ptolemy's exact birthday and where he was born are a mystery. We know he lived in Alexandria, a famous city in Egypt. At that time, Egypt was part of the powerful Roman Empire.

Because his name included "Claudius," it's thought he was a Roman citizen. He studied the ideas of Greek thinkers. He also used ancient observations from Babylon to help with his own studies of the Moon.

Ptolemy passed away in Alexandria. The exact year is not known, but historians believe it was sometime between 160 and 175 AD.

His Name and Background

The name "Ptolemy" was common in ancient times. Many kings of Egypt after Alexander the Great were also named Ptolemy. However, our Ptolemy was not part of that royal family. He was a scholar, not a king!

His full name, Claudius Ptolemaeus, shows he was likely a Roman citizen. This was a special status back then. He wrote all his books in Koine Greek, the common language of scholars in that era.

Ptolemy's Amazing Astronomy

Ptolemy spent a lot of his time studying the stars and planets. About half of his surviving books are all about astronomy!

The Almagest: A Universe Explained

Ptolemy's most famous book is the Almagest. It's the only complete ancient book on astronomy that we still have today. It was like the ultimate guide to the universe for over a thousand years.

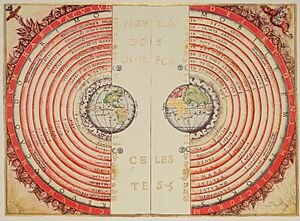

In the Almagest, Ptolemy explained his model of the Solar System. He believed that Earth was at the center, and the Sun, Moon, and planets revolved around it. This idea is called the geocentric model. He used clever geometric models to explain how the celestial bodies moved.

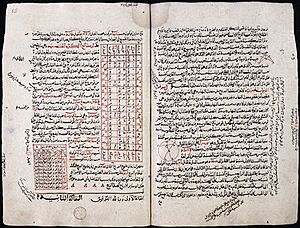

He also created tables to help predict where planets would be in the future or where they were in the past. The Almagest even included a star catalogue, listing many constellations. This catalogue was based on earlier work by another astronomer named Hipparchus.

For centuries, people across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa relied on the Almagest. It was the main textbook for understanding the cosmos until new ideas, like the heliocentric model (Sun at the center), came along during the Scientific Revolution.

How Science Evolves: Checking Old Data

Modern scientists love to study ancient works like the Almagest. They use today's technology to check Ptolemy's observations. Sometimes, they find small differences or patterns of errors.

For example, some scientists noticed that Ptolemy's measurements seemed a bit off. This led to discussions about how accurate his observations truly were.

However, science is always growing and changing! In 2022, exciting new fragments of Hipparchus's lost star catalogue were found. These discoveries helped show that Ptolemy used many sources, including his own observations, to create his star catalogue. This means he didn't just copy others. It reminds us that understanding history and science is a continuous journey of discovery!

Handy Tables: Quick Calculations

Ptolemy also created the Handy Tables. These were like quick reference guides for astronomers and astrologers. They contained all the numbers needed to calculate the positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets. They also helped predict eclipses. These tables were very useful for making astronomical calculations easier.

Planetary Hypotheses: The Universe's Structure

In his book Planetary Hypotheses, Ptolemy described the universe as a series of nested spheres. Imagine giant, invisible spheres, one inside the other, carrying the planets. He even tried to calculate the size of the universe based on his models. He estimated the Sun was about 1,210 Earth radii away! (Today, we know it's much further, about 23,450 radii).

This book also explained how to build models to show the planets' movements. These models were like ancient versions of an orrery, helping people visualize the geocentric universe.

Other Astronomical Discoveries

Ptolemy wrote other shorter works too:

- The Analemma: This book showed how to find the Sun's position using special diagrams.

- The Phaseis: This was a star calendar or almanac. It listed when stars would appear and disappear throughout the year.

- The Planisphaerium: This work explained how to project celestial circles onto a flat surface. This was important for making maps of the sky.

He also left an inscription at a temple in Canopus, Egypt. It described his main ideas about how the universe worked. More recently, in 2023, archaeologists found a manuscript with instructions for building an astronomical tool called a meteoroscope. Scientists believe Ptolemy wrote these instructions!

Other Important Books by Ptolemy

The Geography: Mapping the Ancient World

Ptolemy's Geography is his second most famous work. It was a guide on how to draw maps of the world. He used geographical coordinates to place cities and features accurately.

He built upon the work of earlier mapmakers. Ptolemy's big contribution was creating a huge list of about 8,000 places. For many of these, he provided coordinates like latitude and longitude. This allowed people to create detailed maps.

Ptolemy's maps showed the known world, from the Atlantic Ocean to parts of China. He knew he was only mapping a small part of the entire globe. His work helped shape how maps were made for centuries.

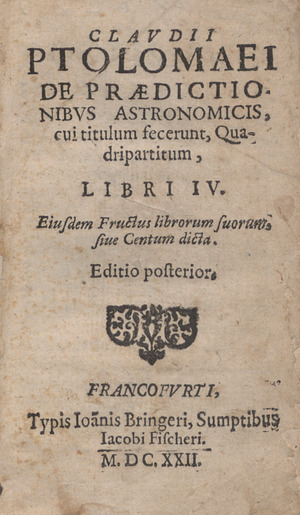

The Tetrabiblos: Stars and Human Life

Ptolemy also wrote a book called the Tetrabiblos, which means "Four Books." This book was about astrology. In ancient times, many people believed that the positions of stars and planets could influence events on Earth and human lives.

Ptolemy tried to explain these ideas in a logical way, using the science of his time. He explored how planets might affect things like temperature and moisture.

Much of the Tetrabiblos came from older sources. Ptolemy used ideas from the philosopher Aristotle, such as the four qualities: hot, cold, wet, and dry. He wanted to show that astrology was a logical and natural study, not just superstition.

The Tetrabiblos was incredibly influential. After it was written, it was copied and studied by many scholars.

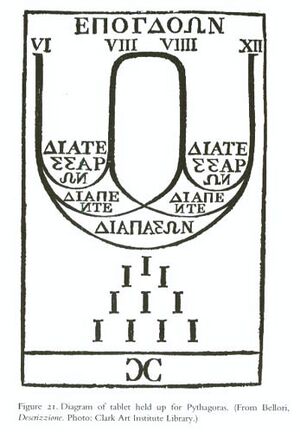

The Harmonics: The Math of Music

Ptolemy was also interested in music! His book Harmonics explored the mathematics behind music. He studied how different musical notes and scales are related through numbers and ratios.

He even built a special instrument called a monochord. This tool helped him measure and test musical pitches. He showed how different mathematical ratios create sounds that we find pleasant. Ptolemy's work helped us understand the science of sound and music.

The Optics: How We See

Ptolemy's book Optics was about how we see things. He wrote about reflection (like in a mirror) and refraction (how light bends when it passes through water or glass).

He tried to explain why objects appear to have different sizes or shapes. For example, he discussed why the Moon looks bigger when it's near the horizon. This book was an important step in understanding how our eyes work and how light behaves.

Things Named After Ptolemy

Ptolemy was such an important figure that many things are named in his honor:

- There's a large crater on the Moon called Ptolemaeus.

- There's also a crater on Mars named Ptolemaeus.

- An asteroid in space is called 4001 Ptolemaeus.

- A beautiful group of stars, Messier 7, is sometimes known as the Ptolemy Cluster.

- In mathematics, there's Ptolemy's theorem, which helps us understand distances in certain shapes.

- The Ptolemy Project at the University of California, Berkeley, is a modern research project. It focuses on designing complex computer systems.

Images for kids

-

An old drawing (1508) of Ptolemy being guided by Urania, the Greek goddess of astronomy.

See also

In Spanish: Claudio Ptolomeo para niños

In Spanish: Claudio Ptolomeo para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |