Tetrabiblos facts for kids

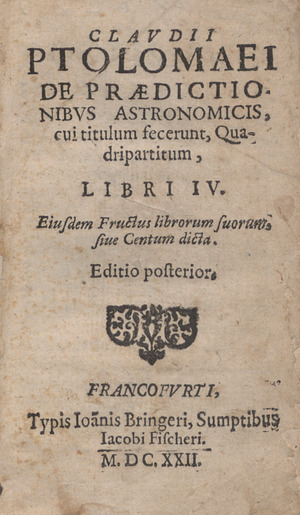

Opening page of Tetrabiblos: 15th-century Latin printed edition of the 12th-century translation of Plato of Tivoli; published in Venice by Erhard Ratdolt, 1484.

|

|

| Author | Claudius Ptolemy |

|---|---|

| Original title | Apotelesmatika |

| Language | Greek |

| Subject | Astrology |

|

Publication date

|

2nd century |

Tetrabiblos is a famous ancient book about astrology. The name means "Four Books" in Greek. It was written in the 2nd century by a well-known scholar from Alexandria named Claudius Ptolemy. In Latin, the book was called the Quadripartitum, which also means "Four Parts."

Ptolemy also wrote a very important book on astronomy called the Almagest. The Tetrabiblos was meant to be a companion to it. While the Almagest studied the movement of stars and planets, the Tetrabiblos explained how these movements were thought to affect life on Earth.

For over 1,500 years, the Tetrabiblos was the most important book on astrology in Europe and the Middle East. It was so respected that it was even studied in universities during the Renaissance. The book helped people see astrology as a natural and serious subject.

Contents

Who Was Claudius Ptolemy?

Claudius Ptolemy lived around 90 to 168 AD. He was a brilliant Greek scholar who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, which was part of the Roman Empire. He was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer, and astrologer.

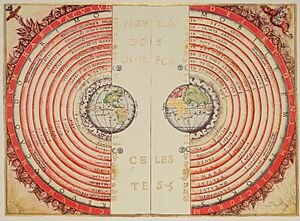

Ptolemy is famous for his scientific books that were used for centuries. His book Geography was a guide to the world's geography. His astronomy book, the Almagest, described a model of the universe with the Earth at the center. This geocentric model was believed for more than 1,400 years. Because he was such a respected scientist, his book on astrology, the Tetrabiblos, was also taken very seriously.

An Important Book for Over 1,000 Years

The Tetrabiblos was incredibly influential. After it was written, it was copied and studied by many scholars. In the 9th century, it was translated into Arabic and became a key text for astrologers in the Islamic world.

Later, in the 12th century, the book was translated into Latin. This brought Ptolemy's ideas to Europe. Thinkers like Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas connected Ptolemy's astrology with Christian beliefs. This allowed astrology to be taught in famous universities, often as part of medical studies.

The book laid down the main rules for astrology during the Renaissance. Even today, people who study the history of science and philosophy read the Tetrabiblos to understand ancient ideas.

Ptolemy tried to explain astrology using the science and philosophy of his time. He used ideas from the philosopher Aristotle, such as the four qualities: hot, cold, wet, and dry. He wanted to show that astrology was a logical and natural study, not just superstition.

What's Inside the Tetrabiblos?

The Tetrabiblos is divided into four books, each covering different topics. Ptolemy organized everything in a systematic way, which was one reason the book was so popular.

Book I: The Basics of Astrology

The first book explains the basic principles of astrology. Ptolemy describes the planets, the stars, and the twelve signs of the zodiac. He explains the "powers" of each planet. For example, he described Mars as hot and dry, while Jupiter was seen as warm and moist.

He also explains how the planets and signs are connected to the four seasons. This book sets up all the rules that are used in the rest of the Tetrabiblos. Ptolemy's goal was to create a logical system for understanding astrology.

Book II: Astrology for Whole Countries

The second book is about what was called "mundane astrology." This was the use of astrology to make predictions for entire nations, cities, or groups of people.

Ptolemy explained how different regions of the world were connected to different zodiac signs. He also wrote about how events like eclipses and the appearance of comets were thought to predict major events like wars, famines, or even changes in the weather.

Book III: Your Personality and Health

The third book focuses on individuals. It explains how to create and interpret a natal chart, or a map of the stars at the moment a person is born. This is often called a horoscope.

This book covers topics that are part of a person from birth. This includes family, physical appearance, and natural talents. It also discusses health and how a person's body might be affected by different planetary influences. Ptolemy also wrote about the "soul," which included a person's mind, thoughts, and feelings.

Book IV: Your Life's Journey

The fourth book continues with predictions for an individual's life. It deals with events and circumstances that happen after birth.

This book covers topics like wealth, social standing, and what kind of job a person might have. It also discusses marriage, friendships, and travel. Ptolemy explained how astrologers could compare the birth charts of two people to see if they would get along.

The Seven Ages of Life

At the end of Book IV, Ptolemy describes the "seven ages of life." He connected each stage of a person's life to one of the seven classical planets (the Sun, Moon, and the five planets visible without a telescope).

Here is a simple summary of his idea:

- The Moon (first 4 years): Babyhood, a time of growth and change.

- Mercury (next 10 years): Childhood, when the mind and ability to speak develop.

- Venus (next 8 years): Youth, a time of strong emotions and friendships.

- The Sun (next 19 years): Young adulthood, a time for ambition and taking on responsibility.

- Mars (next 15 years): Middle age, a time of hard work and challenges.

- Jupiter (next 12 years): Maturity, a time for wisdom, respect, and looking back on life.

- Saturn (the final years): Old age, a time of rest and reflection.

A Book That Traveled the World

No original copies of the Tetrabiblos written by Ptolemy himself have survived. We know about the book because it was carefully copied by hand for centuries. It was also translated into many different languages.

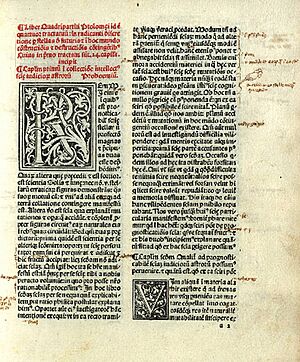

The book was first translated from Greek into Arabic in the 9th century. From Arabic, it was translated into Latin in the 12th century. These translations helped spread Ptolemy's ideas throughout the Islamic world and Europe. The first printed edition of the Greek text appeared in 1535. Because it was copied and translated so many times, there are small differences between some versions of the book.

Images for kids

-

Joachim Camerarius (1500–1574). He translated the first printed Greek edition of the Tetrabiblos.

See also

- Babylonian astronomy

- Greek astronomy

- Ptolemy's world map

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |