Babylonian astronomy facts for kids

Babylonian astronomy was how people in ancient Mesopotamia studied and kept records of objects in the sky. They used a special number system called sexagesimal, which was based on sixty instead of ten (like our modern decimal system). This system made it easier to work with very big or very small numbers.

Around 800 to 600 BC, Babylonian sky-watchers started a new way of studying the sky. They began to use careful observation and logic to predict how planets would move. This was a big step for astronomy and how people thought about science. Some experts even call it a "scientific revolution." This new way of thinking influenced Greek and Hellenistic astrology later on. People often called these wise sky-watchers "Chaldeans." They were like priests and scribes who specialized in understanding the stars and predicting the future. Babylonian astronomy helped create modern astrology and spread it across the ancient Greek and Roman world. They divided the sky into 360 degrees, then into 12 sections of 30 degrees each, creating the 12 zodiac signs.

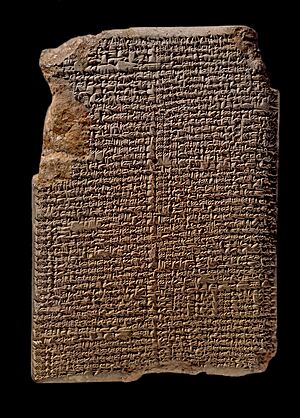

Most of what we know about Babylonian astronomy comes from broken pieces of clay tablets. These tablets contain daily records, tables of planet positions (called ephemerides), and instructions. Even though much is missing, these pieces show that Babylonian astronomy was the first to use math to describe what happens in the sky. All later scientific astronomy, from the Greeks to India, Islamic cultures, and the West, built on what the Babylonians started.

Contents

Early Babylonian Sky-Watching

An interesting object called the ivory prism was found in the ancient city of Nineveh. At first, people thought it was for a game. But later, they figured out it was a tool to help calculate how celestial bodies and constellations moved.

Babylonian astronomers were the first to create the zodiac signs. They divided the sky into three parts, each with thirty degrees, and named them after the star groups found in those sections.

The MUL.APIN is a collection of tablets that lists stars and constellations. It also includes ways to predict when planets would rise and set with the sun. It even describes how to measure the length of daylight using water clocks, gnomons (like sundials), shadows, and adding extra days to the calendar. Another text, the Babylonian GU, arranged stars in "strings" to measure their positions and time intervals.

Understanding Planets

The Babylonians were the first known civilization to have a working idea of how planets moved. The oldest surviving text about planets is the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa. This tablet, copied in the 7th century BC, lists observations of the planet Venus. These observations might go back as far as 2000 BC! Babylonian sky-watchers also laid the groundwork for what became Western astrology. The Enuma anu enlil, written around 700 BC, lists predictions and how they relate to things happening in the sky, including planet movements.

What They Believed About the Universe

We don't know much about what ancient Babylonian astronomers believed about the universe itself. This is because many of their writings are broken, and their astronomy was often separate from their ideas about how the world was created. However, we can find some clues about their beliefs in their stories and myths.

Sky Predictions (Omens)

People in Mesopotamia believed that gods could show future events to humans through signs, called omens. Sometimes these signs came from animal insides, but most often, they believed omens could be read from the sky. Since sky omens happened without human help, they were seen as very powerful. But people also believed that the bad events these omens predicted could be avoided.

The Omen Compendia, a Babylonian text, tells us that ancient Mesopotamians thought omens could be prevented. This text also describes special Sumerian rituals to stop evil, called "nam-bur-bi" (later "namburbu" in Akkadian). The god Ea was believed to send these omens. Eclipses were seen as the most dangerous omens.

The Enuma Anu Enlil is a series of clay tablets that shows different sky omens observed by Babylonian astronomers. The Sun and Moon were thought to have great power as omens. Records from Nineveh and Babylon (around 2500-670 BC) show lunar omens. For example, "When the moon disappears, evil will befall the land. When the moon disappears out of its reckoning, an eclipse will take place."

Ancient Astrolabes

The astrolabes (not the later tool for measuring stars) are some of the earliest cuneiform tablets that talk about astronomy. They date back to the Old Babylonian Kingdom (around 1800 to 1100 BC). These tablets list thirty-six stars connected to the months of the year. No complete texts have been found, but experts have put together information from different fragments.

The thirty-six stars in the astrolabes likely came from the sky-watching traditions of three Mesopotamian city-states: Elam, Akkad, and Amurru. Each region followed twelve stars, which together make up the thirty-six stars in the astrolabes. These twelve stars also matched the months of the year. During the time of King Hammurabi, these three traditions were combined. This led to a more scientific way of studying the sky, as the old traditions became less important. The increased use of science is shown by how the stars from these three regions were arranged according to the paths of the gods Ea, Anu, and Enlil, a system also found in the MUL.APIN.

The MUL.APIN Tablets

MUL.APIN is a set of two clay tablets (Tablet 1 and Tablet 2) that describe Babylonian astronomy. They record things like the movement of celestial bodies and notes on solstices (the longest and shortest days) and eclipses. Each tablet is divided into smaller sections. These tablets were created around the same time as the astrolabes and the Enuma Anu Enlil, as they share similar ideas and math.

Tablet 1 contains information similar to astrolabe B. This suggests that the authors used the same sources for some of their information. This tablet has six lists of stars that relate to sixty constellations in the charted paths of the three Babylonian star groups: Ea, Anu, and Enlil. It also adds to the paths of Anu and Enlil, which are not found in astrolabe B.

Calendar, Math, and Sky-Watching

Studying the Sun, Moon, and other sky objects helped shape Mesopotamian culture. Looking at the sky led to the creation of a calendar and advanced math. While the Egyptians in North Africa also developed a calendar (based on the sun), the Babylonian calendar was based on the moon. Some historians think the Babylonians might have adopted a simple leap year idea from the Egyptians. The Babylonian leap year was different from ours; it involved adding a thirteenth month to help the calendar match the growing seasons better.

Babylonian priests were responsible for developing new math to better calculate how sky objects moved. One of the first known Babylonian astronomers was a priest named Nabu-rimanni. He was a priest for the moon god and is known for writing tables to calculate lunar and eclipse events, along with other complex math. His work was later used by astronomers during the Seleucid dynasty.

Strange Red Skies

Scientists at the University of Tsukuba studied ancient Assyrian clay tablets. These tablets reported unusual red skies, which might have been aurorae (like the Northern Lights) caused by geomagnetic storms between 680 and 650 BC.

Later Babylonian Astronomy

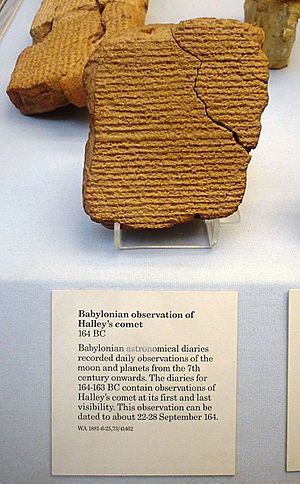

Later Babylonian astronomy refers to the sky-watching done by Chaldean astronomers during the Neo-Babylonian, Achaemenid, Seleucid, and Parthian periods. Their careful records in Babylonian astronomical diaries helped them notice a repeating 18-year cycle of lunar eclipses, known as the Saros cycle.

Math and Shapes in the Sky

Even though we don't have many complete writings on later Babylonian planet theories, it seems most Chaldean astronomers focused on tables of planet positions rather than deep theories. It was thought that their models for predicting planet movements were mostly based on observations and math, without much use of geometry or complex ideas about the universe. However, recent studies of newly found clay tablets (from 350 to 50 BC) show that Babylonian astronomers sometimes used geometric methods to describe how Jupiter moved over time. This was a very advanced idea for their time.

Babylonian astronomy was mostly separate from their ideas about the universe. Unlike Greek astronomers who preferred perfect circles for orbits, Babylonian astronomers did not have such a strong preference.

Important discoveries by Chaldean astronomers during this time include finding eclipse cycles and saros cycles, and making many very accurate observations. For example, they noticed that the Sun's movement along the ecliptic (its path in the sky) was not always the same speed. They didn't know why, but today we know it's because Earth moves in an elliptic orbit around the Sun, speeding up when closer and slowing down when farther away.

The Idea of a Sun-Centered System

The only known planet model from the Chaldean astronomers is from Seleucus of Seleucia (born 190 BC). He supported the Greek idea of heliocentrism, which means the Sun is at the center of the universe. Seleucus is mentioned by ancient writers like Plutarch. The Greek geographer Strabo listed Seleucus as one of the most important astronomers from the Hellenistic city of Seleuceia. Their original works were in the Akkadian language and later translated into Greek.

Seleucus was unique because he was the only one known to support the idea that the Earth rotated on its own axis and also revolved around the Sun. According to Plutarch, Seleucus even proved this idea using logic, though we don't know his exact arguments.

Some historians believe his arguments might have been related to tides. Seleucus correctly thought that tides were caused by the Moon, although he believed the Earth's atmosphere played a role. He noticed that tides changed in different parts of the world. According to Strabo, Seleucus was the first to say that tides are due to the Moon's pull, and their height depends on the Moon's position relative to the Sun.

Another historian, Bartel Leendert van der Waerden, suggests Seleucus might have proved the sun-centered theory by figuring out the math for a geometric model and developing ways to calculate planet positions using it. He might have used trigonometry, a type of math available at his time.

None of Seleucus's original writings have survived, but a small part of his work exists in an Arabic translation, mentioned by the Persian philosopher Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi.

How Babylonians Influenced Greek Astronomy

Many writings from ancient Greek and Hellenistic scholars (like mathematicians, astronomers, and geographers) have been saved. However, the amazing achievements in these fields by earlier civilizations, especially in Babylonia, were forgotten for a long time. After important ancient sites were discovered in the 1800s, many cuneiform writings on clay tablets were found, some of them about astronomy. Most of these astronomical tablets have been studied and published. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus wrote that the Greeks learned things like the gnomon (for telling time by shadows) and the idea of dividing the day into two halves of twelve hours from the Babylonians.

Influence on Hipparchus and Ptolemy

In 1900, a scholar named Franz Xaver Kugler showed that Ptolemy, a famous Greek astronomer, wrote that Hipparchus (another Greek astronomer) improved his knowledge of the Moon's cycles by comparing his own observations with those made earlier by "the Chaldeans." Kugler found that the Moon's cycles Ptolemy credited to Hipparchus were already being used in Babylonian tables of planet positions. It seems Hipparchus simply confirmed the accuracy of what he learned from the Chaldeans with his own observations. Later, a 2nd-century papyrus (an ancient paper) was found that contained calculations for the Moon using the same Babylonian system, but written in Greek.

Historians have found clues that people in Athens during the late 5th century BC might have known about Babylonian astronomy. For example, the writer Xenophon recorded that Socrates told his students to study astronomy enough to tell the time of night from the stars. This skill is also mentioned in a poem by Aratos, which talks about telling time using the zodiac signs.

See also

- Babylonian astrology

- Babylonian calendar

- Babylonian mathematics

- Babylonian star catalogues

- Egyptian astronomy

- History of astronomy (Section on Mesopotamia)

- MUL.APIN

- Pleiades

- Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |