Memphis, Egypt facts for kids

Memphis was an important ancient city in Egypt. It was the capital city for a long time, especially during the Old Kingdom of Egypt. This was from when it was built until about 2200 BC. Later, it was also a capital for shorter times during the New Kingdom. Memphis was always a major center for ruling the country throughout ancient history.

Its old Egyptian name was Ineb Hedj, which means "The White Walls." The name "Memphis" comes from the Greek way of saying the Egyptian name of Pepi I's pyramid, which was Men-nefer. This name later became Menfe in Coptic. Today, towns like Mit Rahina, Dahshur, Saqqara, Abusir, Abu Gorab, and Zawyet el'Aryan are all located where ancient Memphis used to be. These places are south of Cairo (29°50′58.8″N 31°15′15.4″E / 29.849667°N 31.254278°E).

Memphis was also known as Ankh Tawy in Ancient Egypt. This means "That which binds the Two Lands." The city got this name because it was in a perfect spot between Upper and Lower Egypt. This made it a very important place.

The ruins of Memphis are about 20 kilometers (12 miles) south of Cairo. They are on the west side of the Nile River. In the Bible, Memphis is called Moph or Noph.

History of Memphis

How Memphis Was Founded

A Greek historian named Herodotus said that the city was started around 3100 BC. He believed it was founded by a king named Menes. Menes was said to have united the two parts of Egypt into one kingdom. Some experts think King Menes might be a legendary figure, like Romulus and Remus who founded Rome.

It is more likely that Egypt became one country slowly over time. Different areas developed strong cultural ties and traded with each other. However, it is still believed that Memphis was the first capital of ancient Egypt. Many Egyptologists now think that the legendary Menes was actually a historical king named Narmer. The Palette of Narmer shows him conquering the Nile Delta in Lower Egypt. This event is from around 3100 BC, which fits with the story of Egypt becoming united.

How Many People Lived in Memphis?

It's hard to know exactly how many people lived in Memphis. Some experts, like T. Chandler, believe that Memphis had about 30,000 people. This would have made it the largest city in the world from its founding until about 2250 BC. It was also very large again from 1557 to 1400 BC.

However, other experts, like K. A. Bard, think the population was smaller. They estimate that about 6,000 people lived in Memphis during the Old Kingdom.

Why Memphis Was Important

Memphis was the capital of Ancient Egypt for many years during the Old Kingdom. It became very famous and powerful during the 6th Dynasty. This was because it was the main center for worshipping Ptah. Ptah was the Egyptian god of creation and art.

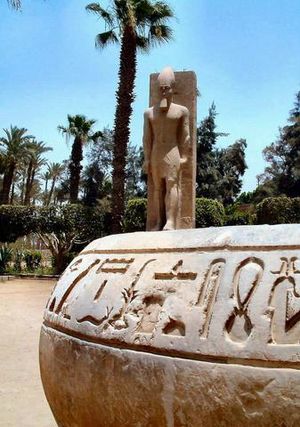

A huge alabaster sphinx, weighing about 80 tons, still stands guard at the Temple of Ptah. This sphinx reminds us of how powerful and important the city once was. Memphis became less important after the 18th Dynasty. This was when Thebes grew in power and the New Kingdom began.

Later, Memphis became important again under Persian rulers. But then, when Alexandria was founded, Memphis became the second most important city. Under the Roman Empire, Alexandria remained the top city. Memphis stayed the second city of Egypt until the city of Fustat was built in 641 AD. After that, Memphis was mostly left empty. Its stones were often taken to build other nearby settlements. By the 12th century, it was still an impressive ruin. But soon, it became just low mounds and scattered stones.

What Remains of Memphis Today

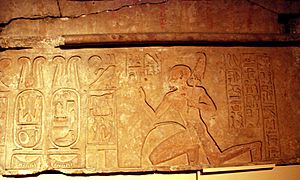

During the New Kingdom, especially under the Nineteenth dynasty, Memphis grew a lot in power and size. It even competed with Thebes in politics and architecture. A chapel built by Seti I for Ptah shows this growth. After more than a hundred years of digging, archaeologists have slowly figured out how the ancient city was laid out.

The Great Temple of Ptah

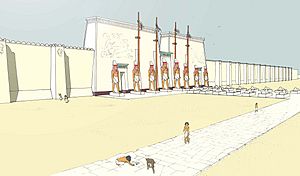

The Hout-ka-Ptah was the biggest and most important temple in ancient Memphis. Its name means "Castle of the ka of Ptah." It was built to worship the god Ptah, who was believed to be the creator god. This temple was a very important building in the city. It took up a large area in the city's center.

Over many centuries, people added to the temple and worshipped there. It became one of the three most important places of worship in Ancient Egypt. The other two were the great temples of Horus in Heliopolis and Amun in Thebes.

Most of what we know about this ancient temple comes from the writings of Herodotus. He was a Greek historian who visited the site long after the New Kingdom had ended. Herodotus said that King Menes himself had founded the temple. He also wrote that only priests and kings were allowed inside the main part of the building. However, he did not describe what the temple looked like.

Archaeological digs over the last century have slowly uncovered the temple's ruins. They show a huge walled area with several large gates. These gates were on the south, west, and east walls.

The remains of the great temple are now an open-air museum. It is near the giant colossus (large statue) of Ramesses II. This statue originally marked the southern entrance of the temple. In this same area, a large sphinx statue was found in the 1800s. It is from the Eighteenth dynasty, probably made during the time of Amenhotep II or Thutmose IV. It is one of the best examples of this type of statue still in its original place.

The outdoor museum also has many other statues, large figures, sphinxes, and parts of buildings. However, most of the things found here have been sold to major museums around the world. Many of them can be seen at the Cairo Museum.

We don't know exactly what the temple looked like. We only know about the main entrances to its outer walls. Recently, giant statues that decorated the gates or towers have been found. These statues are from the time of Ramesses II. This pharaoh also built at least three smaller shrines inside the temple area. These shrines were for worshipping specific gods.

Temple of Ptah of Ramesses II

This smaller temple was next to the southwest corner of the larger Temple of Ptah. It was built for the deified Ramesses II, meaning Ramesses II was worshipped as a god. It also honored three main gods: Horus, Ptah, and Amun. Its full name was the Temple of Ptah of Ramesses, Beloved of Amun, God, Ruler of Heliopolis.

Archaeologist Ahmed Badawy found its ruins in 1942. Rudolf Anthes dug it up in 1955. The digs uncovered a religious building with a tower, a courtyard for offerings, and a porch with columns. Behind that was a hall with pillars and a three-part holy room. All of this was surrounded by walls made of mud bricks. The newest outer parts of the temple are from the New Kingdom era.

The temple faced east, towards a paved path with other religious buildings. Digs in this area show that the southern part of the city had many religious buildings. They were especially dedicated to the god Ptah, who was the main god of Memphis.

Temple of Ptah and Sekhmet of Ramesses II

This small temple is located further east, near the great statue of Ramesses. It is from the Nineteenth dynasty. It seems to have been built for Ptah and his wife, the goddess Sekhmet. It also honored Ramesses II, who was worshipped as a god. Its ruins are not as well preserved as others nearby. This is because its limestone foundations seem to have been taken for other uses after the city was abandoned.

Two giant statues from the Middle Kingdom originally stood at the front of this temple. They faced west. These statues are now in the Museum of Memphis. They show the pharaoh walking, wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt, called the Hedjet.

Temple of Ptah of Merneptah

In the southeast part of the Great Temple complex, Merneptah built a new shrine. Merneptah was a pharaoh from the Nineteenth dynasty. He built it to honor Ptah, the city's main god. William Matthew Flinders Petrie discovered this temple in the early 1900s. He found a carving that he thought showed the Greek god Proteus, mentioned by Herodotus.

Clarence Stanley Fisher dug at the site during World War I. The digging started in the front part of the temple. This part is a large courtyard, about 15 square meters. It opens to the south with a big door that has carvings of the pharaoh's name and titles for Ptah. Only this part of the temple has been uncovered. The rest of the building still needs to be explored further north.

During the digs, archaeologists found the first signs of a building made of mud brick. This turned out to be a large palace for ceremonies, built next to the temple. Some important stone pieces from the temple were given by Egypt to the museum at the University of Pennsylvania. This museum helped pay for the dig. Other pieces stayed at the Museum in Cairo.

The temple was used throughout the rest of the New Kingdom. This is shown by records of people joining the temple during the reigns of later pharaohs. After that, it was slowly left empty and used for other things by regular people. The city's activity gradually buried it. Studies of the ground layers show that by the Late Period, it was already in ruins. Soon, new buildings covered it.

Temple of Hathor

This small temple for the goddess Hathor was found south of the great wall of the Hout-Ka-Ptah. Abdullah al-Sayed Mahmud discovered it in the 1970s. It also dates from the time of Ramesses II. It was built for Hathor, who was called "Lady of the Sycamore." Its design is similar to small temple-shrines found especially at Karnak.

Based on its size, it doesn't seem to be a major temple for the goddess. But it is the only building found so far in the city's ruins that was dedicated to her.

Experts believe this shrine was mainly used for parades during big religious festivals. A larger temple for Hathor, perhaps one of the most important in the country, is thought to have existed elsewhere in the city. However, it has not been found yet. A dip in the ground, similar to one near the great temple of Ptah, might show where it is. Archaeologists think it could hold the remains of a wall and a large monument. Ancient writings support this idea.

Other Temples in Memphis

Herodotus described a temple of Astarte. It was located in the area where Phoenicians lived when Herodotus visited the city. A temple for the goddess Neith was said to be north of the Temple of Ptah. Neither of these temples has been found yet.

Memphis likely had many other temples for gods who were connected to Ptah. Some of these holy places are mentioned in ancient hieroglyphs. But they have not yet been found among the city's ruins. Surveys and digs are still happening near Mit Rahina. These will probably help us learn more about the layout of the ancient religious city.

Also, a temple for Mithras from the Roman period has been found north of Memphis.

Temple of Sekhmet

A temple for the goddess Sekhmet, who was Ptah's wife, has not been found yet. But Egyptian writings confirm it existed.

It might be inside the area of the Hout-ka-Ptah. This is suggested by several discoveries made in the ruins of the complex in the late 1800s. These include a stone block mentioning a "great door" with Sekhmet's title. Also, a column has an inscription from Ramesses II calling himself "beloved of Sekhmet." The Great Harris Papyrus also shows that a statue of Sekhmet was made with statues of Ptah and their son, Nefertem. This was during the reign of Ramesses III, for the gods of Memphis in the main temple.

Temple of Apis

The Temple of Apis in Memphis was the main temple for worshipping the bull Apis. Apis was believed to be a living form of the god Ptah. Famous historians like Herodotus, Diodorus, and Strabo wrote about it. But its exact location has not been found among the ruins of the ancient capital.

Herodotus said that the temple's courtyard had many columns and giant statues. He believed it was built during the time of Psammetichus I.

The Greek historian Strabo visited the site with Roman soldiers after their victory against Cleopatra. He wrote that the temple had two rooms: one for the bull and one for its mother. He said it was all built near the temple of Ptah. At the temple, Apis was used as an oracle. People believed his movements could predict the future. His breath was thought to cure sickness, and his presence was believed to bring strength. He had a window in the temple where people could see him. On special holidays, he was led through the city streets, decorated with jewelry and flowers.

In 1941, archaeologist Ahmed Badawy found the first remains in Memphis that showed the god Apis. This site was inside the area of the great temple of Ptah. It turned out to be a special room for preparing the sacred bull's body for burial. A stone tablet found at Saqqara shows that Nectanebo II had ordered this building to be repaired. Pieces from the Thirtieth dynasty have been found in the northern part of the room. This confirms when that part of the temple was rebuilt. It is likely that this room was part of the larger Temple of Apis mentioned by ancient writers. This sacred part of the temple might be the only part that has survived. It would confirm what Strabo and Diodorus said, that the temple was near the temple of Ptah.

Most of the Apis statues we know about come from burial places called Serapeum. These are located northwest of Memphis, at Saqqara. The oldest burials found there are from the time of Amenhotep III.

Temple of Amun

During the Twenty-first dynasty, a shrine for the great god Amun was built by Siamun. It was located south of the temple of Ptah. This temple (or temples) was probably for the Theban Triad. This group included Amun, his wife Mut, and their son Khonsu. This was the Upper Egyptian version of the Memphis Triad (Ptah, Sekhmet, and Nefertem).

Temple of Aten

A temple for Aten in Memphis is mentioned in hieroglyphs. These were found in the tombs of important people from Memphis at the end of the Eighteenth dynasty. These tombs were found at Saqqara. One of these tombs belonged to Tutankhamun. He started his career under Akhenaten as a "steward of the temple of Aten in Memphis."

Since the first digs in Memphis in the late 1800s and early 1900s, items have been found in different parts of the city. These items suggest there was a building for worshipping the sun disc. The exact location of this building is unknown. Different ideas have been suggested based on where the items from the Amarna period were found.

Statues of Ramesses II

The ruins of ancient Memphis have given us many sculptures of the pharaoh Ramesses II.

Inside the museum in Memphis, there is a giant statue of the pharaoh. It is made of huge limestone and is about 10 meters (33 feet) long. Italian archaeologist Giovanni Caviglia found it in 1820 near the southern gate of the temple of Ptah. Because the bottom part of the statue is broken, it is now displayed lying on its back. Some of its original colors are still partly visible. The statue's beauty comes from its perfect details of the human body.

Caviglia offered the statue to Leopold II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. This was done with the help of Ippolito Rosellini. Rosellini told the Duke about the huge costs of moving it. He even thought it would be necessary to cut the giant statue into pieces. The British viceroy Muhammad Ali offered to give it to the British Museum. But the museum said no because it would be too hard to ship such a huge statue to London. So, it stayed in the archaeological area of Memphis, in a museum built to protect it.

This giant statue was one of a pair that once stood at the entrance to the Temple of Ptah and Sekhmet. The other statue was found in the same year by Caviglia. It was put back together in the 1950s to its full standing height of 11 meters (36 feet). It was first displayed in Bab Al-Hadid square in Cairo, which was then renamed Ramses Square. It was decided that this was not a good place for it. So, in 2006, it was moved to a temporary spot in Giza. It is currently being restored there. It is planned to be shown at the entrance of the Grand Egyptian Museum, which is set to open soon. A copy of the statues stands in the Heliopolis area of Cairo.

Images for kids

-

Memphis and its burial ground Saqqara as seen from the International Space Station

-

Ritual object showing the god Nefertem, who was mainly worshipped in Memphis, The Walters Art Museum

-

The famous stepped Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, the Memphis necropolis

-

James Rennell's map of Memphis and Cairo in 1799, showing how the Nile river changed course

-

Museum worker cleaning the Rameses II colossus

-

Picture of Ptah found on the walls of the Temple of Hathor

-

The alabaster sphinx found outside the Temple of Ptah

See also

In Spanish: Menfis para niños

In Spanish: Menfis para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |