Flinders Petrie facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir

Flinders Petrie

|

|

|---|---|

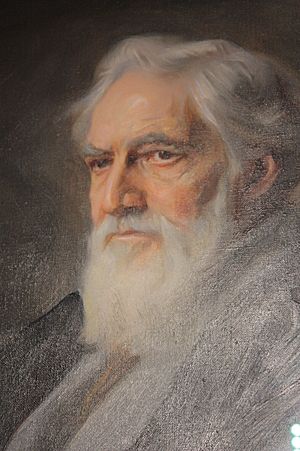

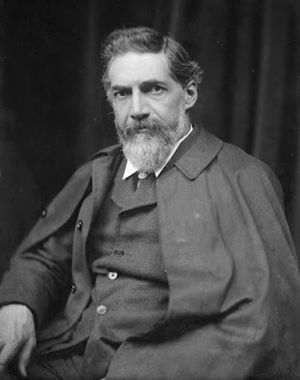

Petrie in 1903

|

|

| Born |

William Matthew Flinders Petrie

3 June 1853 |

| Died | 28 July 1942 (aged 89) |

| Resting place | Mount Zion Cemetery |

| Known for | Proto-Sinaitic script, Merneptah Stele, pottery seriation |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Egyptology |

| Doctoral students | Howard Carter |

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (born June 3, 1853 – died July 28, 1942), often called Sir Flinders Petrie, was a British Egyptologist. He was a pioneer in how archaeologists systematically study and preserve ancient objects. He held the first professor job for Egyptology in the United Kingdom. He excavated many important ancient sites in Egypt with his wife, Hilda Urlin.

Many people think his most famous discovery was the Merneptah Stele. Petrie himself agreed with this. Another very important find was in 1905. He correctly identified the Proto-Sinaitic script. This ancient writing system is the ancestor of almost all alphabetic scripts we use today.

Petrie created a way to date archaeological layers. He did this by studying pottery and ceramic finds. He is also known for his controversial views about different groups of people. He believed that people from Northern Europe were better than those from Southern Europe.

Contents

Early Life and First Discoveries

Petrie was born on June 3, 1853, in Charlton, England. His father, William Petrie, was an electrical engineer. His mother, Anne, was the daughter of Captain Matthew Flinders. Captain Flinders was famous for sailing around Australia.

Petrie was taught at home and did not go to a formal school. His father taught him how to survey land very accurately. This skill was very important for his later work in archaeology. When he was eight, he learned French, Latin, and Greek.

At age eight, he also shared his first archaeological idea. He heard about people digging up a Roman villa. He was upset that they were digging roughly. He said the earth should be removed "inch by inch." This way, everything could be seen exactly as it was found. He later wrote that all his future work came from this early idea.

Becoming a Professor

In 1892, a special job was created at University College London. It was called the Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology. This job was funded by Amelia Edwards, who was a big supporter of Petrie. She wanted him to be the first person to hold this position.

Even after becoming a professor, Petrie kept digging in Egypt. He also trained many future archaeologists. In 1904, Petrie wrote a book called "Methods and Aims in Archaeology." This book explained his ideas about how archaeology should be done. He believed that an archaeologist needed to know a lot and be very curious.

In 1913, Petrie sold his large collection of Egyptian artifacts to University College, London. This collection is now in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. One of his students, Howard Carter, later became famous for discovering the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922.

Archaeological Expeditions

Exploring British Sites

As a teenager, Petrie studied ancient British monuments. He started with a Roman-British camp near his home. When he was 19, he made the most accurate survey of Stonehenge.

Surveying the Giza Pyramids

In 1880, Petrie traveled to Egypt. He wanted to make an accurate survey of Giza. He was the first to properly study how the pyramids were built. Many theories existed, but none were based on real observations.

Petrie's reports on his Giza survey were very accurate. They disproved many old theories. His work still provides important information about the pyramid area today. He was shocked by how quickly ancient monuments were being destroyed. He felt it was his duty to save as much as he could.

Working with the Egypt Exploration Fund

After returning to England, Petrie met Amelia Edwards. She was a journalist and supported the Egypt Exploration Fund. She was impressed by his scientific methods. In 1884, Petrie went back to Egypt to start new excavations.

Digging at Tanis and Tell Nebesheh

He first worked at Tanis, a site from the New Kingdom. He changed the way digs were run. He took full control himself, instead of relying on foremen. This meant workers could take more time and find smaller, important objects.

In 1886, he excavated at Tell Nebesheh. Here, he found a royal sphinx. This sphinx is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Discoveries Along the Nile

Petrie ran out of money for a while. So, in 1887, he cruised the Nile River. He took many photographs to record sites. He also climbed cliffs at Sehel Island to draw and photograph thousands of ancient Egyptian writings. These writings recorded things like trips to Nubia and times of famine.

Uncovering Fayum Burials

His funding was renewed, and he went to the burial site at Fayum. He was interested in burials from after 30 BC. He found tombs that were still sealed and 60 famous mummy portraits. He learned that these mummies were kept with their families for generations before burial.

He sent half of these portraits to the Egyptian department of antiquities. But when he saw they were being damaged, he demanded them back. He sent 48 portraits to London for a special display at the British Museum.

Work in Palestine

In 1890, Petrie began working in Palestine. His excavation of Tell el-Hesi was the first scientific dig in the Holy Land. He also surveyed tombs in Jerusalem. There, he found that two different units of length had been used in ancient times.

Amarna Discoveries

From 1891, he worked at the temple of Aten in Tell-el-Amarna. He found a large painted floor showing gardens and hunting scenes. Tourists damaged this floor, so Petrie's copies are important for knowing what it looked like.

Finding the Merneptah Stele

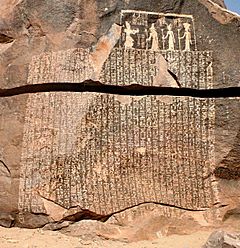

In 1896, Petrie and his team were digging at a temple in Luxor. They found a large stone slab, over ten feet tall. It had writing on it. When they turned it over, they found an inscription by King Merneptah. It described his victories.

A German expert, Wilhelm Spiegelberg, read the text. He was puzzled by one name: "I.si.ri.ar?" Petrie quickly realized it meant "Israel!" This was the first time the word "Israel" was found in an ancient Egyptian text. Petrie predicted this discovery would become very famous, and it did.

Later Excavations

From 1889 to 1899, Petrie led a team excavating many cemeteries between Hu and Abadiya, Egypt. They found graves from different time periods, including Predynastic, Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, and Roman times.

Discovering the Proto-Sinaitic Script

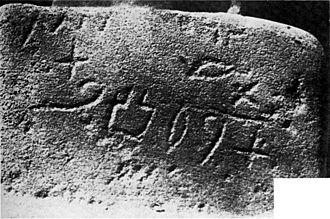

In 1905, Petrie and his wife Hilda were digging in the Sinai Peninsula. At Serabit el-Khadim, an ancient turquoise mine, Petrie found inscriptions. He saw that they had hieroglyphic characters. But he realized the writing was fully alphabetic, not a mix of pictures and sounds like Egyptian hieroglyphs.

He thought the miners had created this script themselves. They used signs borrowed from hieroglyphs. He published his findings the next year. He had found and correctly identified the Proto-Sinaitic script. This script is the ancestor of almost all alphabetic writing systems used today.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1923, Petrie was made a knight for his important work in British Archaeology and Egyptology.

Focus on Palestine

After 1926, his work mainly focused on Palestine. He excavated several important sites there, including Tell Jemmeh and Tell el-Ajjul. He discovered the ruins of ten cities at Tell el-Hesi.

New Excavation System

In 1928, while digging a large cemetery at Luxor, he created a new excavation system. This system included comparison charts for finds. It is still used by archaeologists today.

Moving to Jerusalem and Death

In 1933, Petrie retired from his professorship. He moved permanently to Jerusalem with Lady Petrie. Sir Flinders Petrie died in Jerusalem on July 28, 1942. He was buried in the Protestant Cemetery on Mount Zion.

He had wanted to donate his head to the Royal College of Surgeons of London for study. During World War II, his head was delayed in transit. It was stored in a jar, and its label fell off. For a time, no one knew whose head it was. It was eventually identified and is now stored at the Royal College of Surgeons.

Personal Life

Petrie married Hilda Urlin in London in 1896. They had two children, John and Ann. The family lived in Hampstead, London. John Flinders Petrie became a famous mathematician.

His Impact on Archaeology

Scientific Digging Methods

Flinders Petrie's careful way of recording and studying artifacts set new standards. He believed in noting and comparing even the smallest details.

Dating with Pottery

He was the first to use a method called seriation in Egyptology. This meant linking different pottery styles to specific time periods. It was a new way to figure out the age of a site.

Teacher and Guide

Petrie also taught and trained many archaeologists, including Howard Carter. In 1953, his wife Hilda created a scholarship for students to travel to Egypt.

Artifacts in Museums

Thousands of artifacts found by Petrie are now in museums around the world.

The Petrie Medal

The Petrie Medal was created to celebrate his 70th birthday. It is given every three years for important work in archaeology. Petrie himself received the first medal in 1925.

Controversial Views

Petrie held controversial views about different groups of people. He believed that some groups were naturally superior to others. These ideas influenced his academic opinions. For example, he thought that ancient Egyptian culture came from an invading group of people. He believed this group conquered the native people and brought in a higher civilization. These views are now seen as wrong and harmful.

Palestinian Archaeology

His work in Palestinian archaeology was featured in an exhibition called "A Future for the Past: Petrie's Palestinian Collection."

Memorial

In 2012, over a hundred people gathered at Petrie's grave to mark 70 years since his death. His headstone has only his name and an ankh symbol, which means "life" in ancient Egypt.

Published Works

Petrie published a total of 97 books. Many of his discoveries were shared with the Royal Archaeological Society.

- Tel el-Hesy (Lachish). London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- "The Tomb-Cutter's Cubits at Jerusalem," Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly, 1892 Vol. 24: 24–35.

Some of His Books

- Naukratis, Pt. I, Egypt Exploration Fund, 1886.

- Tanis, Pt. I, Egypt Exploration Fund, 1889.

- Egyptian decorative art, London, 1895.

- The Religion of Ancient Egypt (1906)

- Migrations, Anthropological Inst. of Great Britain and Ireland, 1906.

- Janus in Modern Life, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1907.

- Eastern Exploration – Past and Future London: Constable and Company Ltd., 1918.

- Some Sources of Human History, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1919.

- The Status of the Jews in Egypt, G. Allen & Unwin, 1922.

- The Revolutions of Civilization, Harper & Brothers, 1922.

Images for kids

-

Flinders Petrie, painted by George Frederic Watts, 1900.

See also

In Spanish: William Matthew Flinders Petrie para niños

In Spanish: William Matthew Flinders Petrie para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |