Hilda Petrie facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hilda Petrie

|

|

|---|---|

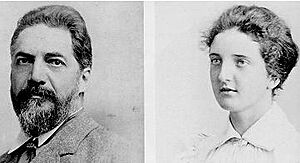

Hilda and Flinders Petrie, 1903.

|

|

| Born | 1871 Dublin, Ireland

|

| Died | 1957 (aged 85–86) London, England

|

| Spouse(s) | Flinders Petrie |

Hilda Mary Isabel Petrie (born Urlin; 1871–1957) was an amazing British Egyptologist. An Egyptologist is someone who studies ancient Egypt. She was married to Flinders Petrie, who is often called the "father of scientific archaeology." This means he helped make archaeology a more careful and scientific study.

Hilda studied geology, which is the study of Earth's rocks and minerals. When she was 25, Flinders Petrie hired her as an artist. She was very good at drawing and copying things accurately. This job led to their marriage and a partnership that lasted their whole lives. Hilda and Flinders Petrie traveled and worked together. They excavated (dug up) and recorded many ancient sites in Egypt, and later in Palestine. She even directed some excavations herself! She worked in tough and sometimes dangerous places to copy hieroglyphs (ancient Egyptian writing) from tombs and draw maps of sites. She also helped write reports for the Egypt Exploration Fund.

In 1905, Flinders Petrie started the British School of Archaeology in Egypt in London. Hilda became its secretary and helped raise money. This support allowed them to continue their important digs. Hilda took part in archaeological work throughout her married life, except when her two children were very young. Her work was published in books, and she also gave public talks in London and other places.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Hilda Mary Isabel Urlin was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1871. She was the youngest of five daughters. Her parents, Richard and Mary Urlin, were English but had lived in Ireland for a long time. When Hilda was four, her family moved back to London, England.

Hilda was taught at home by a governess, along with other children her age. As she grew up, she loved going on bicycle trips with her friend Beatrice Orme. They explored the countryside, visited old churches, and made brass rubbings. This is a fun way to copy designs from old brass plates, often found in churches. One of her childhood friends was Philippa Fawcett, whose mother, Dame Millicent Fawcett, was a leader in the women's right to vote movement. Philippa later became a very famous mathematician.

Hilda preferred the countryside and didn't like London at first. But as she got older, she enjoyed visiting its museums and art galleries. When she was a teenager, she was known for her red hair and was quite pretty. She even modeled for the painter Henry Holiday for some of his famous paintings. Hilda studied at King's College for Women. There, she took a geology course with Professor Harry Seeley. She would go on field trips with a notebook and a hammer, ready to explore rocks. She also took classes in drawing exact copies, a skill she was very good at.

When she was 25, Henry Holiday introduced her to Professor Flinders Petrie at University College London. He needed someone who could make very accurate copies, just like Hilda could. They got married on November 26, 1896, and left for Egypt the very next day!

The Petries had two children, John (born 1907) and Ann (born 1909). They lived in Hampstead, London. Today, there's a special blue plaque on their old home at 5 Cannon Place. Their son, John Flinders Petrie, became a mathematician. He even has a shape named after him, the Petrie polygon. Hilda passed away in 1957 from a stroke. She died across the street from where she and her husband had worked to create England's first training school for archaeologists.

Archaeological Adventures

Hilda first went to Egypt on November 25, 1896. After that, she joined her husband on almost every dig, except for a few years when their children were very young.

Digging in Egypt

After a few days in Cairo and a visit to Giza, the Petries traveled to Upper Egypt. They were part of an expedition to dig for the Egypt Exploration Fund. Their first big dig was in a cemetery behind the temple of Dendera, which is about 70 kilometers (43 miles) north of Luxor.

During this trip, Hilda worked deep inside the tombs. She would climb down rope ladders to copy scenes and writings found far underground. One huge stone coffin had about 20,000 hieroglyphs to record! Hilda spent many days lying on the ground to copy them all. She also drew pictures of pots, beads, scarabs (beetle-shaped amulets), and other small items found during the dig. Sometimes, she wrote the daily journal that was sent weekly to report their progress. She also helped Flinders Petrie write the final reports about their discoveries.

In 1898, Hilda helped survey the cemetery sites of Abadiyeh and Hu. She used special charts to identify the shapes of pots, slates, and flints. After Flinders recorded these finds on the map, Hilda wrote the grave number on each item. Flinders Petrie praised her work in his report that year. He wrote that his wife helped with surveying, cataloging, marking objects, and drawing all the tomb plans. Her work continued into 1898–99. She drew almost all the pottery marks and helped arrange the plates for publication. She also helped register and care for the pottery and number the skeletons. Hilda and Flinders also made a map of an ancient fort together.

In the winter of 1902, Hilda was given control of her own excavation at Abydos. Her team included Margaret Murray and an artist named Miss Hansard. They tried to dig a very difficult and dangerous site. The year before, they had found what looked like the entrance to a huge underground tomb. This deep dig was always at risk of caving in. When the wind blew, loose sand and shifting stones threatened the workers. The work was eventually stopped. The report to the Egypt Exploration Fund that year highlighted Hilda Petrie's contributions: "My wife was busy drawing almost all season; especially on the tiring work of nearly 400 flints, and the exact copies of inscriptions."

In 1904, Hilda Petrie helped with work at Ehnasya. She drew almost half of the pictures for the book about the site. The next year, she stayed at Saqqara to copy carvings in some ancient tombs. She then joined Flinders Petrie and Lina Eckenstein at a temple site on a hilltop at Serabit el-Khadim. There were many carved stones, statues, and stelae (stone slabs) there. Some of these had a new, unknown writing system, which was called Sinaitic. Hilda's skill at copying was very helpful. Hilda and Lina Eckenstein, who was 48 and knew many things, traveled across Sinai with just one guide. Eckenstein later wrote several books about her time in Sinai.

Working at the British School of Archaeology

When the British School of Archaeology in Egypt was started in London in 1905, Hilda became its secretary. She worked to raise money and find new supporters. This was also when her two children were born. She wrote to important and wealthy people to ask for support for Flinders Petrie's work. She also oversaw the publishing of their discoveries and gave public lectures in London and other parts of the UK.

More Work in Egypt

Hilda went back to Egypt in January 1913 to join Flinders Petrie at Kafr Ammar. Three painted tombs from the Twelfth Dynasty (an ancient Egyptian period) had been found nearby at Riqqeh. They needed to be recorded quickly. This work was again difficult and dangerous, but they managed it. Hilda published a chapter in the final report about these tombs. It included her plans and copies of the wall paintings and coffins.

During the First World War

When World War I began in 1914, Hilda focused on helping women's organizations. She used her fundraising skills as the Honorary Secretary of the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service. This group provided hospital care for the Serbian division of the Russian army. Later, she received the Serbian order of St Sava for her efforts. During this time, the Petries also studied ancient carvings made in the chalk hills of the UK.

In 1919, Hilda and Flinders started digging in Egypt again. In 1921, Hilda excavated a Coptic hermit's cell in the Western hills at Abydos. A Coptic hermit was a Christian who lived alone in the desert. Her plans and drawings of the cave were published in the excavation report that year. She also wrote a description of the cave and its painted decorations.

Digging in Palestine and Jerusalem

In 1926, the Petries' focus shifted to ancient fortresses in Palestine. This happened because new rules made it harder to dig up bodies in Egypt and export ancient items. These rules came after the famous discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922. Hilda arrived in Gaza on November 26, 1926. There, she managed, registered, and paid the excavation workers. However, she spent most of the next three years in England trying to raise money for the work. Sadly, the work in Palestine didn't attract as much support as their Egyptian digs.

The Petries' last excavation season in Gaza was in 1931. They thought the huge mound called Tell el Ajull would provide years of work. But this didn't happen. Problems with the excavations caused their work to stop.

By 1933, the Petries had moved to Jerusalem. For two seasons between 1935 and 1937, they dug at the mound of Sheikh Zoweyd. This had been a frontier fortress between Egypt and Asia. A planned dig in 1939 was canceled when bandits attacked and robbed their camp.

Later Years and Publications

Flinders Petrie passed away on July 29, 1942. Hilda Petrie spent the rest of the war living at the American School of Palestine. She worked on editing his papers, which she planned to send to the new library of the Department of Antiquities in Khartoum.

In 1947, Hilda returned to Hampstead, England. She finished up the business of the British School. In 1952, she was finally able to publish the tomb carvings she had copied way back in 1905 at Saqqara. She passed away in 1957.

Published Works

- Egyptian Hieroglyphs of the first and second dynasties, drawn by Hilda Petrie, Quaritch, London 1927

- Seven Memphite tomb chapels, Inscriptions by Margaret A[lice] Murray. Drawings by F. Hansard, F. Kingsford, and L. Eckenstein. Drawings and plans by H. F. Petrie, British School of Egyptian Archaeology and Quaritch, London 1952

- Side Notes on the Bible: From Flinders Petrie's Discoveries, Search Publishing Company Limited, London 1933.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Hilda Petrie para niños

In Spanish: Hilda Petrie para niños