Margaret Murray facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Margaret Murray

|

|

|---|---|

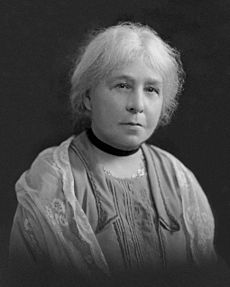

Murray in 1928

|

|

| Born |

Margaret Alice Murray

13 July 1863 |

| Died | 13 November 1963 (aged 100) Welwyn, Hertfordshire, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University College London |

| Occupation | Egyptologist, archaeologist, anthropologist, folklorist |

| Employer | University College London (1898–1935) |

| Parent(s) | James Murray, Margaret Murray |

Margaret Alice Murray (born July 13, 1863 – died November 13, 1963) was a British scholar who studied ancient Egypt, dug up old sites, and explored human cultures and folklore. She was the first woman in the United Kingdom to become a lecturer in archaeology. She taught at University College London (UCL) from 1898 to 1935. Later in life, she was the President of the Folklore Society from 1953 to 1955. She wrote many books and articles throughout her long career.

Margaret Murray was born in Calcutta, British India, to a well-off English family. She spent her childhood in India, Britain, and Germany. She trained as a nurse and a social worker. In 1894, she started studying Egyptology at UCL. There, she became good friends with the head of the department, Flinders Petrie. He helped her publish her first academic papers and made her a Junior Professor in 1898.

In 1902–03, she joined Petrie's digs in Abydos, Egypt. She discovered the Osireion temple there. The next year, she explored the Saqqara cemetery. These discoveries made her well-known in Egyptology. To earn more money, she taught public classes at the British Museum and Manchester Museum. In 1908, at the Manchester Museum, she publicly unwrapped a mummy named Khnum-nakht. This was the first time a woman had done this in public. Murray also wrote several books about ancient Egypt for everyone to read.

Murray was also involved in the early movement for women's rights. She joined the Women's Social and Political Union. She worked hard to improve the status of women at UCL. During World War I, she couldn't go back to Egypt. So, she focused on her "witch-cult hypothesis." This was a theory that the witch trials were an attempt to destroy an old, pre-Christian religion that worshipped a Horned God. Even though scholars later disagreed with her theory, it became very popular. It also greatly influenced the new religion of Wicca.

From 1921 to 1931, Murray dug at ancient sites in Malta and Menorca. This deepened her interest in folklore. She received an honorary doctorate in 1927. She became an Assistant Professor in 1928 and retired from UCL in 1935. After retiring, she helped with digs in Palestine and Jordan. She continued to give lectures and publish books until she died at 100 years old.

Her work in Egyptology and archaeology was highly praised. People called her "The Grand Old Woman of Egyptology." However, after her death, her contributions were often overshadowed by Petrie's. On the other hand, her ideas about witchcraft and folklore are not accepted by scholars today. But her witch-cult theory had a big impact on religion and literature. She is even called the "Grandmother of Wicca."

Contents

Her Early Life

Growing Up in India and Europe

Margaret Murray was born on July 13, 1863, in Calcutta, British India. She was from a British family living in India. She lived in Calcutta with her parents, James and Margaret Murray, her older sister Mary, and her grandmother and great-grandmother. Her father, James, was a successful businessman. Her mother, Margaret, was a missionary who taught Indian women.

Even though they lived in the European part of Calcutta, Margaret met Indian people through her family's servants and during holidays. A historian named Amara Thornton thinks that Murray's childhood in India influenced her whole life. She believes Murray had a mixed identity, being both British and Indian. Margaret never went to a formal school as a child. She was proud that she never had to take an exam before going to university.

In 1870, Margaret and Mary went to Britain to live with their uncle John. He was a vicar. He gave them a strong Christian education. He also believed that women were not as good as men, but Margaret later disagreed with these ideas. However, he sparked Margaret's interest in archaeology by taking her to see local ancient sites. In 1873, their mother came to Europe and took them to Bonn, Germany. There, both girls learned to speak German very well.

They returned to Calcutta in 1875 and stayed until 1877. Then they moved back to England, settling in Sydenham, South London. They often visited The Crystal Palace. In 1880, Margaret returned to Calcutta for seven years. She became a nurse at the Calcutta General Hospital. She helped during a cholera outbreak. In 1887, she moved back to England, to Rugby. She became a social worker, helping people who were struggling. When her father retired, she lived with him in Bushey Heath until he died in 1891. In 1893, she visited her sister in Madras, India.

Starting Her Studies at UCL

Her mother and sister encouraged Margaret to enroll at the new Egyptology department at University College London (UCL). This department was started with money from Amelia Edwards, who helped create the Egypt Exploration Fund. The famous archaeologist Sir William Flinders Petrie led the department. Murray started her studies at UCL in January 1894, at age 30. Most of her classmates were women or older men. She took classes in Ancient Egyptian and Coptic languages.

Murray quickly got to know Petrie. She became his copyist and illustrator, drawing for his excavation reports. He helped her write her first research paper, published in 1895. Murray became Petrie's unofficial assistant. She started teaching some language classes when others were away. In 1898, she became a Junior Lecturer, teaching language courses in the Egyptology department. This made her the first female archaeology lecturer in the UK. She worked at UCL two days a week and spent the other days caring for her sick mother. Over time, she also taught courses on Ancient Egyptian history, religion, and language. Many of her students became important Egyptologists. She also taught evening classes at the British Museum to earn more money.

Discoveries in Egypt and Feminism

Uncovering Ancient Secrets

Murray had no experience digging in the field. So, in 1902–03, she went to Egypt to join Petrie's excavations at Abydos. Petrie and his wife, Hilda Petrie, had been digging there since 1899. Murray first joined as a nurse. But Petrie taught her how to excavate and gave her a senior role. This caused some problems with the male excavators, who didn't like taking orders from a woman. This experience, and talking with other female excavators, made Murray openly support women's rights.

While digging at Abydos, Murray found the Osireion. This was a temple for the god Osiris, built by Pharaoh Seti I. She wrote a report about her findings in 1904, called The Osireion at Abydos. In it, she studied the writings found at the site to understand what the building was used for.

In 1903–04, Murray returned to Egypt. Petrie asked her to explore the Saqqara cemetery, which was from the Old Kingdom. Murray didn't have official permission to dig. Instead, she copied the writings from ten tombs that had been found in the 1860s. She published her findings in 1905 as Saqqara Mastabas I. She didn't publish the translations until 1937. Both The Osireion at Abydos and Saqqara Mastabas I were very important in the Egyptology community. Petrie recognized how much Murray helped his own work.

Fighting for Women's Rights

When she returned to London, Murray became very active in the women's rights movement. She gave her time and money to the cause. She took part in protests and marches, like the Mud March of 1907. She kept her actions quiet to maintain her good reputation in academia. Murray also pushed for women to have more opportunities in her own career. She helped other women in archaeology and in universities.

Because women couldn't use the men's common room at UCL, she successfully campaigned for a common room for women. Later, she made sure a bigger, better room was used for this purpose. It was later named the Margaret Murray Room. She became friends with another female lecturer, Winifred Smith. Together, they worked to improve the status of women at the university. Murray was especially annoyed by female staff who were afraid to ask for what they deserved. She also believed students should have healthy and affordable lunches. For many years, she served on the UCL Refectory Committee.

Exploring British Folklore

Museums across the UK asked Murray for advice on their Egyptian collections. She cataloged artifacts in Dublin, Edinburgh, and for the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. She was even made a Fellow of the latter. Petrie had connections with the Egyptology section of Manchester Museum. Many of his finds were kept there. Murray often traveled to the museum to catalog these items. She also lectured there regularly in 1906–07.

In 1907, Petrie found the Tomb of the Two Brothers, which held two Egyptian priests. It was decided that Murray would publicly unwrap one of the mummies, Khnum-nakht. This happened at the museum in May 1908. It was the first time a woman had led a public mummy unwrapping. Over 500 people watched, and it got a lot of attention from the press. Murray wanted to show how important the unwrapping was for understanding ancient Egyptian burial practices. She criticized people who thought it was wrong. She said that "every trace of ancient remains must be carefully studied... without fear of the outcry of the ignorant." She later wrote a book about her study of the two bodies, The Tomb of the Two Brothers. This book remained important for understanding Middle Kingdom mummification.

Murray believed in public education. She wanted to combine the public's interest in ancient Egypt with real academic knowledge. So, she wrote several books for a general audience. In 1905, she published Elementary Egyptian Grammar. In 1911, she published Elementary Coptic (Sahidic) Grammar. In 1913, she wrote Ancient Egyptian Legends. She was very happy when Howard Carter found the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun in 1922, as it increased public interest in Egyptology.

From 1911 until his death in 1940, Murray was a close friend of the anthropologist Charles Gabriel Seligman. They wrote many papers together about Egyptology for an anthropological audience. Many of these were published in Man. Seligman suggested she become a member of the Institute in 1916.

In 1914, Petrie started an academic journal called Ancient Egypt. Since he was often away digging, Murray often acted as the editor. She also published many articles and book reviews in the journal.

When World War I started in 1914, Petrie and other staff couldn't go to Egypt to dig. Instead, they spent time organizing the artifacts they had collected. To help with the war, Murray volunteered as a nurse in France. After getting sick, she recovered in Glastonbury, Somerset. There, she became interested in Glastonbury Abbey and the old stories about King Arthur and the Holy Grail. She wrote a paper called "Egyptian Elements in the Grail Romance." However, few people agreed with her ideas, and some scholars criticized it.

Later Life and Big Ideas

Her Witch-Cult Theory

When I suddenly realised that the so-called Devil was simply a disguised man I was startled, almost alarmed, by the way the recorded facts fell into place, and showed that the witches were members of an old and primitive form of religion, and the records had been made by members of a new and persecuting form.

Murray's interest in folklore led her to study the witch trials in Europe. In 1917, she published a paper where she first shared her "witch-cult theory." She argued that the witches who were persecuted were actually followers of "a definite religion with beliefs, ritual, and organization." She wrote more about this in her 1921 book, The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. This book got both criticism and support. Many academic reviews were critical, saying she had misunderstood historical records. However, the book was still very influential.

Because of her work, she was asked to write the entry on "witchcraft" for the 1929 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. She used this chance to spread her witch-cult theory. She didn't mention other theories by other scholars. Her entry stayed in the encyclopedia until 1969, making her ideas widely known. People interested in the supernatural liked her ideas about an ancient secret society. Murray joined the Folklore Society in 1927.

She repeated her witch-cult theory in her 1933 book, The God of the Witches. This book was for a general audience, not just scholars. In this book, she made the witch-cult sound more positive, calling it "the Old Religion." She also left out or softened some of the more unpleasant parts she had mentioned before.

Digging in Malta and Menorca

From 1921 to 1927, Murray led archaeological digs on Malta. She was helped by Edith Guest and Gertrude Caton Thompson. She excavated Bronze Age megalithic monuments that were in danger from a new airport. Her three-volume report on these digs became an important publication in Maltese archaeology. During these digs, she also became interested in Malta's folklore. This led to her 1932 book, Maltese Folktales, which included many translated stories. In 1932, Murray returned to Malta to help catalog Bronze Age pottery.

Because of her work in Malta, Louis C. G. Clarke invited her to lead digs on the island of Menorca from 1930 to 1931. With Guest's help, she dug at ancient sites and published Cambridge Excavations in Minorca. Murray also continued to write books about Egyptology for a general audience, like Egyptian Sculpture (1930) and Egyptian Temples (1931). These books received good reviews. In 1925, she led a small dig in Stevenage, but she never published a report about it.

In 1924, UCL made Murray an assistant professor. In 1927, she received an honorary doctorate for her work in Egyptology. That year, she guided Mary of Teck, the Queen, around the Egyptology department during her visit to UCL. Teaching became less demanding, allowing Murray to travel more. She visited Egypt in 1920 and South Africa in 1929. In the early 1930s, she traveled to the Soviet Union to visit museums. In late 1935, she gave lectures in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Estonia.

Even though she reached retirement age in 1927, Murray was reappointed each year until 1935. She then retired from UCL. In 1933, Petrie had retired from UCL and moved to Jerusalem. Murray took over as editor of the Ancient Egypt journal, renaming it Ancient Egypt and the East. The journal stopped publishing in 1935, perhaps because of Murray's retirement. Murray then spent time in Jerusalem, helping the Petries with their dig at Tall al-Ajjul.

Retirement and Continued Work

During her 1935 trip to Palestine, Murray visited Petra in Jordan. She was very interested in the site. In 1937, she returned to do a small dig in some cave dwellings there. She later wrote a report and a guidebook about Petra. Back in England, from 1934 to 1940, Murray helped catalog Egyptian antiquities at Girton College, Cambridge. She also lectured in Egyptology at the university until 1942. Her interest in folklore continued. She wrote an introduction to a book on Lincolnshire folklore, where she discussed how women were better folklorists than men.

During World War II, Murray moved to Cambridge to avoid the bombings in London. She volunteered for a group that educated military personnel for post-war life. She also researched the town's history, but she never published her findings.

After the war, she returned to London. She lived in a small room near UCL and the UCL Institute of Archaeology. She continued to be involved with UCL and used the Institute's library. Most days, she visited the British Museum library. Twice a week, she taught adult classes on Ancient Egyptian history and religion.

Murray continued to make Egyptology popular. In 1949, she published Ancient Egyptian Religious Poetry. That same year, she also published The Splendour That Was Egypt, which brought together many of her UCL lectures. The book suggested that Egypt influenced Greek and Roman society, and thus modern Western society. The book received mixed reviews from archaeologists.

Her Personal Side

Historian Rosalind M. Janssen said that Murray was "remembered with gratitude and immense affection by all her former students." She was a "wise and witty teacher." Murray often socialized with her students outside of class. Archaeologist Ralph Merrifield described her as a "diminutive and kindly scholar, who radiated intelligence and strength of character." Another friend noted that at meetings, she would seem to be dozing, but then suddenly make a sharp, relevant comment. Folklorist Juliette Wood said that many members of the Folklore Society "remember her fondly." She was "especially keen to encourage younger researchers."

One of Murray's friends, E. O. James, said she was "a mine of information and a perpetual inspiration." He added that she was always ready to share her knowledge, even if it went against what other experts believed. Another friend said she was "not at all assertive" and "never thrust her ideas on anyone." She acted like someone who was part of a secret group but never argued about it in public. Archaeologist Glyn Daniel observed that Murray remained mentally sharp even in old age.

Murray never married. She dedicated her life to her work. Historian Kathleen L. Sheppard said that Murray was very committed to sharing knowledge with the public, especially about Egyptology. She "wanted to change the means by which the public obtained knowledge about Egypt's history." Travel was one of her favorite activities, but she couldn't do it often because of time and money limits.

She was raised as a Christian and taught Sunday School. But after becoming an academic, she rejected organized religion. She was known among the Folklore Society as a skeptic and a rationalist. She was critical of organized religion, but she still believed in a higher power. She wrote that she believed in "an unseen over-ruling Power," which science calls Nature and religion calls God.

She also believed in and practiced magic. She would perform curses against people she felt deserved it. In one case, she cursed a fellow academic because she felt his promotion was unfair. She was also said to have made a wax image of Kaiser Wilhelm II and melted it during the First World War. Historian Ruth Whitehouse suggests that these actions might have been more for "mischief" than a real belief in the spells.

Margaret Murray's Legacy

Impact on Archaeology

Historian Ronald Hutton noted that Murray was one of the first women to "make a serious impact upon the world of professional scholarship." Archaeologist Niall Finneran called her "one of the greatest characters of post-war British archaeology." When she died, Daniel called her "the Grand Old Woman of Egyptology." Hutton said that Egyptology was "the core of her academic career." In 2014, Amara Thornton called her "one of Britain's most famous Egyptologists."

However, according to archaeologist Ruth Whitehouse, Murray's work in archaeology and Egyptology was often overlooked. Her work was overshadowed by Petrie's. People often thought of her mainly as Petrie's assistant, not as a scholar in her own right. Whitehouse believes that Murray's reputation declined after her death. This was partly because her witch-cult theory was rejected. Also, women archaeologists were often forgotten in the male-dominated history of the field.

No British folklorist can remember Dr Margaret Murray without embarrassment and a sense of paradox. She is one of the few folklorists whose name became widely known to the public, but among scholars, her reputation is deservedly low; her theory that witches were members of a huge secret society preserving a prehistoric fertility cult through the centuries is now seen to be based on deeply flawed methods and illogical arguments.

In his obituary for Murray, James said her death was "an event of unusual interest and importance" for the Folklore Society and beyond. However, later folklorists like Jacqueline Simpson have called Murray and her witch-cult theory an embarrassment to their field. Simpson suggested that Murray's position as President of the Society might have made historians mistrust folkloristics. Catherine Noble also stated that "Murray caused considerable damage to the study of witchcraft."

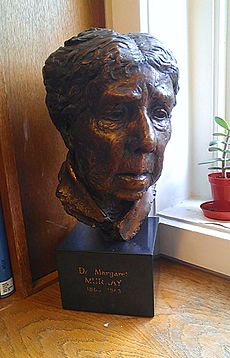

In 1935, UCL started the Margaret Murray Prize. It is given to the student who writes the best dissertation in Egyptology. It is still given out today. In 1969, UCL named a common room after her, but it was changed into an office in 1989. In 1983, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother visited the room and received a copy of Murray's book My First Hundred Years. UCL also has two busts (sculptures of her head and shoulders) of Murray. One is in the Petrie Museum, and the other is in the UCL Institute of Archaeology library.

In 2013, on the 150th anniversary of Murray's birth, Ruth Whitehouse described Murray as "a remarkable woman" whose life was "well worth celebrating."

Influence on Wicca

Margaret Murray's witch-cult theories became the foundation for the modern religion of Wicca. She is often called the "Grandmother of Wicca." Scholar Ethan Doyle White said that her theory "formed the historical narrative around which Wicca built itself." When Wicca appeared in England in the 1940s and 1950s, it claimed to be a survival of this ancient witch-cult.

Wicca's beliefs, with a Horned God and Mother Goddess, came from Murray's ideas. Wiccan groups are called covens, and their meetings are called esbats, both words Murray made popular. Like Murray's witch-cult, Wiccans join through an initiation ceremony. Murray's idea that witches wrote down their spells in a book might have influenced Wicca's Book of Shadows. Wicca's early system of seasonal festivals also came from Murray's ideas.

Historian Philip Heselton suggested that the New Forest coven – an early Wiccan group – was formed around 1935 by people who knew about Murray's theory. Gerald Gardner, who claimed to be part of the New Forest coven, helped make Wicca popular. According to Simpson, Gardner was the only member of the Folklore Society who fully accepted Murray's theory. Murray and Gardner knew each other. Murray wrote the introduction to Gardner's 1954 book Witchcraft Today.

As the religion [of Wicca] emerged, many practitioners saw those who suffered in the [witch trials of the Early Modern] as their forebears, thus adopting the Murrayite witch-cult hypothesis which provided Wicca with a history stretching back far into the reaches of the ancient past. As historians challenged and demolished this theory in the 1960s and 1970s, many Wiccans were shocked.

Murray's theories also influenced other Wiccan traditions. The prominent Wiccan Doreen Valiente searched for other groups that might be survivors of Murray's witch-cult. Valiente continued to believe in Murray's theory even after scholars rejected it. In the US, Murray's writings were used by Aidan A. Kelly to create his Wiccan tradition. They were also used by Zsuzsanna Budapest to establish her feminist-focused tradition of Dianic Wicca.

Over time, many Wiccans learned that scholars did not accept the witch-cult theory. So, belief in its literal truth decreased. Many Wiccans started to see it as a myth that held symbolic truths. Others said that the historical origins didn't matter. They believed Wicca was valid because of the spiritual experiences it gave them. However, some practitioners still strongly defended Murray's theory.

Her Ideas in Books and Movies

Simpson noted that when Murray's theory was published in the Encyclopædia Britannica, it became available to "journalists, film-makers popular novelists and thriller writers." They adopted it with excitement. It influenced the work of writers like Aldous Huxley and Robert Graves. Murray's ideas also shaped how paganism was shown in the historical novels of Rosemary Sutcliff. The American horror author H. P. Lovecraft also used The Witch-Cult in Western Europe in his stories about the fictional cult of Cthulhu.

The author Sylvia Townsend Warner said that Murray's work influenced her 1926 novel Lolly Willowes. Warner even sent a copy of her book to Murray. While Murray described an organized pre-Christian cult, Warner showed a vague family tradition that was explicitly Satanic. In 1927, Warner lectured on witchcraft, showing a strong influence from Murray's work.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Margaret Murray para niños

In Spanish: Margaret Murray para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |