Howard Carter facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Howard Carter

|

|

|---|---|

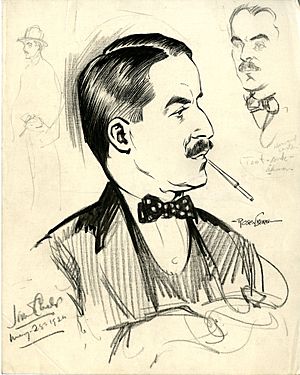

Carter in 1924

|

|

| Born | 9 May 1874 Kensington, England

|

| Died | 2 March 1939 (aged 64) Kensington, England

|

| Known for | Discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Archaeology and Egyptology |

| Signature | |

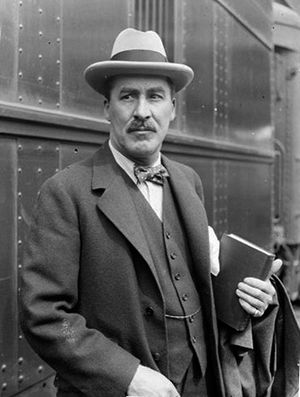

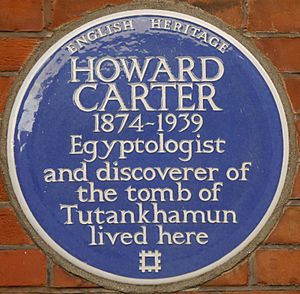

Howard Carter (May 9, 1874 – March 2, 1939) was a British archaeologist and Egyptologist. He is famous for discovering the amazing tomb of the young Pharaoh Tutankhamun in November 1922. This tomb was found in the Valley of the Kings and was the most complete ancient Egyptian tomb ever found.

Contents

Early Life and Training

Howard Carter was born in Kensington, England, on May 9, 1874. He was the youngest of eleven children. His father, Samuel John Carter, was an artist who helped Howard develop his drawing skills.

Howard spent much of his childhood in Swaffham, a town in Norfolk. He did not have much formal schooling. However, he showed a great talent for art. Near Swaffham was Didlington Hall, a large house with many Egyptian artifacts. These sparked Carter's interest in ancient Egypt. In 1891, a lady named Lady Amherst was impressed by his art. She helped him join the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF). He went to Egypt to help Percy Newberry record drawings from ancient tombs at Beni Hasan.

Even at 17, Carter found new ways to copy tomb decorations. In 1892, he worked with Flinders Petrie at Amarna. From 1894 to 1899, he worked with Édouard Naville at Deir el-Bahari. There, he drew the wall carvings in the temple of Queen Hatshepsut.

Working for Egyptian Antiquities

In 1899, Carter became an Inspector of Monuments for Upper Egypt. This was part of the Egyptian Antiquities Service (EAS). He was based in Luxor. He looked after many digs and restoration projects in nearby Thebes. In the Valley of the Kings, he oversaw the work of American archaeologist Theodore M. Davis. Carter was praised for making excavation sites safer and easier to visit. He also created a new system for finding tombs.

In 1905, Carter left the Antiquities Service. This happened after a disagreement with French tourists and Egyptian site guards. Carter supported the Egyptian staff. He refused to apologize when the French complained. He then moved back to Luxor. For almost three years, he had no official job. He made money by painting watercolors for tourists. He also worked as a freelance artist for Theodore Davis.

Discovering Tutankhamun's Tomb

In 1907, Carter started working for Lord Carnarvon. Lord Carnarvon hired him to supervise excavations of nobles' tombs near Thebes. Gaston Maspero, who led the Egyptian Antiquities Service, suggested Carter. He knew Carter used modern archaeological methods. Carter and Lord Carnarvon soon became good friends and worked well together.

In 1914, Lord Carnarvon got permission to dig in the Valley of the Kings. Carter led this work. He planned to search carefully for any tombs that earlier expeditions had missed. He especially wanted to find the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun. However, the First World War soon interrupted their work. Carter spent the war years working for the British government. He eagerly went back to digging in late 1917.

By 1922, Lord Carnarvon was getting tired of not finding much. He thought about stopping the funding. But after talking with Carter, he agreed to pay for one more season of work.

The Great Discovery

Carter returned to the Valley of the Kings. He decided to investigate a line of ancient huts he had left a few seasons earlier. His crew cleared the huts and the rocks beneath them. On November 4, 1922, a young water boy accidentally tripped on a stone. It turned out to be the top of a staircase cut into the rock. Carter had the steps partly dug out. They found the top of a mud-plastered doorway. It had oval seals with hieroglyphic writing, called cartouches. Carter ordered the stairs to be refilled. He sent a telegram to Lord Carnarvon, who arrived from England on November 23. Lord Carnarvon brought his daughter, Lady Evelyn Herbert.

On November 24, 1922, the full staircase was cleared. A seal with Tutankhamun's cartouche was found on the outer doorway. This door was removed. The rubble-filled corridor behind it was cleared. This revealed the door of the tomb itself. On November 26, Carter, with Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn, and assistant Arthur Callender, made a small hole in the top left corner of the doorway. He used a chisel his grandmother had given him. He peered inside with a candle. He saw many gold and ebony treasures still in place. He wasn't sure if it was a tomb or just a storage place. But he saw another sealed doorway between two statues. Lord Carnarvon asked, "Can you see anything?" Carter famously replied: "Yes, wonderful things!" Carter had, in fact, discovered Tutankhamun's tomb (known as KV62).

The tomb was then secured. The next day, it was to be entered with an official from the Egyptian Department of Antiquities. However, that night, Carter, Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn, and Callender secretly entered the tomb. They were the first people in modern times to go inside. Some stories say they also entered the inner burial chamber.

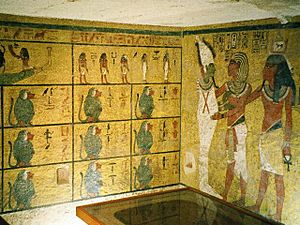

The next morning, November 27, the tomb was inspected with an Egyptian official. Callender set up electric lights. They lit up a huge collection of items. These included gilded couches, chests, thrones, and shrines. They also saw signs of two more rooms. One was the sealed doorway to the inner burial chamber, guarded by two life-size statues of Tutankhamun. Even though there was evidence of ancient break-ins, the tomb was almost untouched. It would eventually be found to contain over 5,000 items.

On November 29, the tomb was officially opened. Many important people and Egyptian officials were there.

Carter realized how big the job would be. He asked for help from the Metropolitan Museum's team. They were working nearby. They agreed to lend staff, including Arthur Mace and photographer Harry Burton. The Egyptian government also loaned chemist Alfred Lucas. The next few months were spent listing and preserving the items. This work was done under the supervision of Pierre Lacau, director general of the Department of Antiquities.

On February 16, 1923, Carter opened the sealed doorway. He confirmed it led to a burial chamber. Inside was the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun. The tomb was considered the best preserved pharaonic tomb ever found. The discovery was big news around the world. Lord Carnarvon sold exclusive reporting rights to The Times newspaper. Only Arthur Merton from that paper was allowed on site. His vivid stories helped make Carter famous with the British public.

In late February 1923, a disagreement between Lord Carnarvon and Carter stopped the excavation for a short time. Work started again in early March after Lord Carnarvon apologized. Later that month, Lord Carnarvon got sick while staying in Luxor. He died in Cairo on April 5, 1923. Lady Carnarvon kept her late husband's permission to dig. This allowed Carter to continue his work.

Carter's careful work of listing and preserving thousands of objects took almost ten years. Most items were moved to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. There were several breaks in the work. One break lasted almost a year in 1924–25. This was due to a dispute over how much control the Egyptian Antiquities Service had. The Egyptian authorities eventually agreed that Carter should finish clearing the tomb. This continued until 1929, with some final work lasting until February 1932.

Despite his amazing discovery, Carter did not receive any special honor from the British government. However, in 1926, he received the Order of the Nile, third class, from King Fuad I of Egypt. He also received an honorary degree from Yale University.

Carter wrote several books about Egyptology. These included Five Years' Exploration at Thebes, co-written with Lord Carnarvon in 1912. He also wrote a three-volume popular account of finding Tutankhamun's tomb. He gave many lectures about the excavation. In 1924, he toured Britain, France, Spain, and the United States. His lectures in New York and other US cities drew large crowds. This sparked a craze for ancient Egypt in America, called Egyptomania. President Calvin Coolidge even asked for a private lecture.

Later Life and Death

After the tomb was fully cleared in 1932, Carter stopped excavation work. He continued to live in his house near Luxor in winter. He also kept a flat in London. As interest in Tutankhamun faded, he lived a quiet life with few close friends.

For many years, he had worked part-time as a dealer for collectors and museums. He continued this role, working for the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Carter died at his London flat on March 2, 1939, at age 64. He had Hodgkin's disease. He was buried in Putney Vale Cemetery in London on March 6. Only nine people attended his funeral.

His love for Egypt remained strong. His gravestone has a quote from Tutankhamun's Wishing Cup: "May your spirit live, may you spend millions of years, you who love Thebes, sitting with your face to the north wind, your eyes beholding happiness" and "O night, spread thy wings over me as the imperishable stars".

See also

In Spanish: Howard Carter para niños

In Spanish: Howard Carter para niños