Hormuzd Rassam facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hormuzd Rassam

ܗܪܡܙܕ ܪܣܐܡ |

|

|---|---|

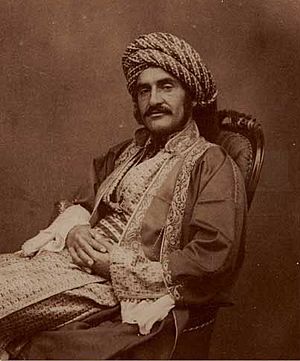

Hormuzd Rassam in Mosul c. 1854

|

|

| Born | October 3, 1826 |

| Died | September 16, 1910 (aged 83) Hove, England

|

| Occupation | Archaeologist, Assyriologist activist, author |

Hormuzd Rassam (Arabic: هرمز رسام; Syriac: ܗܪܡܙܕ ܪܣܐܡ; 1826 – 16 September 1910) was a famous archaeologist and writer. An archaeologist studies human history by digging up old cities and objects. Rassam was also an Assyriologist, meaning he studied the ancient Assyrian people and their language. He made many important discoveries between 1877 and 1882. These included the clay tablets that told the story of the Epic of Gilgamesh. This is one of the oldest known stories in the world!

Hormuzd Rassam is thought to be the first known Middle Eastern and Assyrian archaeologist from the Ottoman Empire. He later moved to the United Kingdom and became a British citizen. He also worked as a diplomat for the British government. He even helped free British diplomats who were held captive in Ethiopia.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Beginnings

Hormuzd Rassam was born in 1826 in Mosul, a city in what is now northern Iraq. At that time, it was part of the Ottoman Empire. His family was Assyrian. His brother was a British Vice-Consul in Mosul. This connection helped Hormuzd get his start in archaeology.

In 1846, when he was 20, Rassam began working for British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard. Layard was on his first expedition in the area. He hired Rassam as a paymaster at Nimrud, an ancient Assyrian site nearby. Layard was very impressed with Rassam's hard work. They became lifelong friends. Layard even helped Rassam travel to England to study at Magdalen College, Oxford for 18 months. After his studies, Rassam joined Layard on his second expedition to Iraq from 1849 to 1851.

Discovering Ancient Stories

After Layard left archaeology for a political career, Rassam continued digging. From 1852 to 1854, he worked at Nimrud and Nineveh. Here, he made some very important discoveries on his own.

One of his most famous finds was a collection of clay tablets. These tablets were later translated by George Smith. They told the story of the Epic of Gilgamesh. This is the world's oldest known written story! The tablets also described a great flood myth. This story was written 1,000 years before the earliest record of the Biblical story of Noah. This discovery caused a lot of discussion at the time about ancient history.

Working as a Diplomat

Rassam later returned to England. With Layard's help, he started a new career in government. He worked for the British Consulate in Aden. He quickly became the First Political Resident there. He helped make many agreements between the British and local leaders.

In 1866, a big problem happened in Ethiopia. British missionaries were taken hostage by Emperor Tewodros II. England decided to send Rassam as an ambassador. He carried a message from Queen Victoria. The hope was to solve the problem peacefully.

Rassam was delayed for about a year. Finally, the Emperor allowed him to enter Ethiopia. Rassam had to take a long route because of rebellions. He eventually met Emperor Tewodros. At first, things looked good. The Emperor gave Rassam many gifts. He also sent the British consul and other hostages to Rassam's camp.

However, the Emperor suddenly changed his mind. He made Rassam a prisoner too. The British hostages were held for two years. Finally, in 1868, English and Indian troops arrived. They were led by Robert Napier, 1st Baron Napier of Magdala. They defeated the Emperor's army and freed the captives.

Some newspapers unfairly criticized Rassam. They said he was not effective in dealing with the Emperor. This showed some unfair ideas people had at the time about people from the "Orient." But Rassam had many supporters, especially in the government. Queen Victoria herself gave him £5,000 for his service as her envoy.

Rassam went back to his archaeological work. But he also did other tasks for the British government. During the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78), he investigated the conditions of Christian communities in Anatolia and Armenia.

More Amazing Discoveries

From 1877 to 1882, Rassam led four expeditions for the British Museum. He made many important discoveries. Many valuable items were sent to the museum. This was possible because of an agreement Layard had made with the Ottoman Sultan. The agreement allowed Rassam to continue excavations and send any finds to England. A representative of the Sultan was present at the digs to check the objects.

In Assyria, Rassam found the Ashurnasirpal temple in Nimrud. He also found the cylinder of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh. He discovered two unique bronze strips from the Balawat Gates. He believed the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon were located at a mound called Babil. He also dug up a palace of Nebuchadnezzar II at Borsippa.

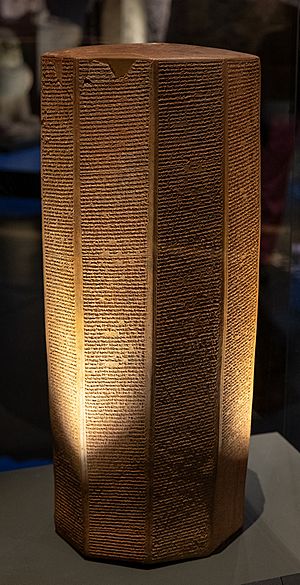

In March 1879, at the site of the Esagila in Babylon, Rassam found the Cyrus Cylinder. This is a famous declaration by Cyrus the Great. It was made in 539 BCE to celebrate the Achaemenid Empire's takeover of Babylonia.

In 1881, at Abu Habba, Rassam discovered the temple of the sun at Sippar. There, he found a Cylinder of Nabonidus. He also found a stone tablet of Nabu-apla-iddina of Babylon. This tablet had a special carving and inscription. Besides these, he found about 50,000 clay tablets that contained records of the temple.

After 1882, Rassam lived mostly in Brighton, England. He wrote books about his archaeological explorations. He also wrote about the ancient Christian peoples of the Near East.

Rassam's Legacy

Hormuzd Rassam's discoveries gained worldwide attention. The Italian Royal Academy of Sciences in Turin gave him a prize of 12,000 francs. He was also chosen as a member of important groups like the Royal Geographical Society.

Some people, like Sir Henry Rawlinson, who helped understand ancient cuneiform writing, argued about who deserved credit for some discoveries. Rawlinson claimed Rassam was just a "digger" who oversaw the work. But Layard defended Rassam, saying he was "one of the honestest and most straightforward fellows I ever knew."

Rassam felt that some of his discoveries were credited to others at the British Museum. In 1893, Rassam sued E. A. Wallis Budge, a keeper at the British Museum, for saying bad things about him. Budge had claimed Rassam used his relatives to sneak antiquities out of Nineveh and only sent "rubbish" to the museum. Rassam was very upset by these claims. The courts supported Rassam. Later archaeological evidence also backed up Rassam's side of the story. By the end of his life, Rassam's achievements were getting more recognition from his fellow archaeologists.

Published Works

- The British Mission to Theodore, King of Abyssinia (1869) - his memories of the mission.

- The Garden of Eden and Biblical Sages (1895)

- Asshur and the Land of Nimrod (1897)

Personal Life

Hormuzd Rassam married an Englishwoman named Anne Eliza Price. They had seven children. Their oldest daughter, Theresa Rassam, born in 1871, became a professional singer. She performed with the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company.

Hormuzd Rassam passed away on September 8, 1910. He was buried in Hove Cemetery. Some of his personal items, like the chains he wore when he was held captive in Ethiopia, were given to Hove Museum. They were on display there for many years.

See also

- List of Assyriologists

- Cyrus Cylinder

- Epic of Gilgamesh