E. A. Wallis Budge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir E. A. Wallis Budge

|

|

|---|---|

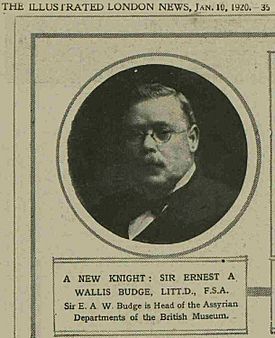

Article announcing Budge's knighthood, 1920

|

|

| Born |

Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge

27 July 1857 |

| Died | 23 November 1934 (aged 77) London, UK

|

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Egyptology, philology |

Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge (born July 27, 1857 – died November 23, 1934) was a British expert in Egyptology (the study of ancient Egypt), Orientalism (the study of Eastern cultures), and Philology (the study of languages). He worked for the famous British Museum and wrote many books about the ancient Near East.

Budge traveled often to Egypt and Sudan for the British Museum. He helped the museum collect many ancient items like cuneiform tablets, old writings (manuscripts), and papyrus scrolls. He wrote many books about ancient Egypt, which helped more people learn about these amazing discoveries. In 1920, he was made a knight for his important work in Egyptology and for the British Museum.

Early Life and Education

E. A. Wallis Budge was born in 1857 in Bodmin, Cornwall, England. He moved to London as a young boy and lived with his aunt and grandmother.

Budge became interested in languages before he was ten years old. At age twelve, in 1869, he started working as a clerk at a company called WHSmith, which sold books. In his free time, he studied Biblical Hebrew and Syriac with a volunteer teacher.

In 1872, Budge became interested in learning the ancient Assyrian language. He also started spending a lot of time at the British Museum. His teacher introduced him to important experts there, like Samuel Birch and George Smith. These experts helped Budge with his studies. Birch even let him study ancient clay tablets called cuneiform in his office.

Budge studied Assyrian in his free time from 1869 to 1878. He often studied during his lunch breaks at St. Paul's Cathedral. The organist there, John Stainer, noticed how hard Budge worked. Stainer wanted to help Budge achieve his dream of becoming a scholar. He contacted important people like W. H. Smith and former Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. They helped raise money for Budge to attend the University of Cambridge.

Budge studied at Cambridge from 1878 to 1883. He learned several Semitic languages like Hebrew, Syriac, Geʽez, and Arabic. He also continued to study Assyrian on his own. During these years, he worked closely with William Wright, a well-known language scholar.

In 1883, he married Dora Helen Emerson. She passed away in 1926. Budge was made a knight in 1920 for his important work in Egyptology and for the British Museum. In the same year, he published his autobiography, By Nile and Tigris. He retired from the British Museum in 1924 and continued to write books until his death in 1934.

Working at the British Museum

In 1883, Budge began working at the British Museum in the Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities. He first worked in the Assyrian section but soon moved to the Egyptian section. He studied the Egyptian language with Samuel Birch until Birch's death in 1885. Budge then continued his studies with the new head of the department, Peter le Page Renouf, until Renouf retired in 1891.

Between 1886 and 1891, the British Museum asked Budge to investigate why ancient clay tablets from their sites in Iraq were appearing in London shops. The museum was buying its "own" tablets at very high prices. Budge's job was to find out how this was happening and to stop it. He also aimed to connect with local dealers in Iraq to buy items at lower prices. Budge also traveled to Istanbul to get permission from the Ottoman Empire to restart excavations at the Iraqi sites.

During his time at the British Museum, Budge also worked to build relationships with local antiquities dealers in Egypt and Iraq. This allowed the museum to buy ancient items directly from them, which was easier and cheaper than digging them up. This was a common way for museums to collect items in the 1800s.

Budge returned from his many trips to Egypt and Iraq with huge collections. These included many cuneiform tablets, Syriac, Coptic, and Greek writings, and important collections of hieroglyphic papyri. Some of his most famous finds were the Papyrus of Ani (a Book of the Dead), a copy of Aristotle's lost Constitution of Athens, and the Amarna letters. Budge's smart and successful collecting helped the British Museum get some of the best Ancient Near East collections in the world. At that time, European museums were all trying to build the biggest and best collections.

In 1900, another expert, Archibald Sayce, told Budge: "You have completely changed the Oriental Department of the Museum! It is now like a real history of civilization shown through objects."

Budge became an assistant keeper in his department after Renouf retired in 1891. He was made the head keeper in 1894 and held this job until 1924, focusing on Egyptology. Budge and other museum collectors in Europe saw having the best collection of Egyptian and Assyrian items as a matter of national pride. There was a lot of competition among them. Museum officials sometimes used special ways to get items, like sending them in diplomatic bags or asking friends in the Egyptian Service of Antiquities to let their boxes pass without being checked. During his time as keeper, Budge was known for being kind and patient when teaching young visitors at the British Museum.

Budge's time as keeper was not without disagreements. In 1893, he had a public dispute with Hormuzd Rassam. Budge had written that Rassam had used his family to take ancient items out of Nineveh and had only sent "rubbish" to the British Museum. Rassam was very upset by these claims. This disagreement became a legal case, and while the judge supported Rassam, the jury did not. After Rassam's death, some people claimed that even though Rassam found most of the ancient items, staff at the British Museum, like Austen Henry Layard, took the credit.

Writing and Social Life

Budge was also a very busy writer. He is especially remembered today for his books on ancient Egyptian religion and his guides to hieroglyphs. Budge believed that the religion of Osiris came from people who lived in Africa.

He wrote in his 1911 book, Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection: "There is no doubt that the beliefs here are from Africa, from the Nile or Sudan regions. I have tried to explain them using evidence from the religions of modern people living along the great rivers of East, West, and Central Africa. If we look at modern African religions, we find their basic beliefs are almost the same as those of ancient Egypt. Since they didn't get these ideas from the Egyptians, it means these beliefs naturally developed in the religious minds of people in certain parts of Africa, remaining similar over time."

Budge's idea that Egyptian religion came from similar religions in northeastern and central Africa was not accepted by most other scholars at the time. Most experts, like Flinders Petrie, believed that ancient Egyptian culture came from an invading group that conquered Egypt long ago.

Budge's books were read by many educated people and those interested in comparing different cultures. For example, James Frazer used some of Budge's ideas about Osiris in his famous book on comparative religion, The Golden Bough. Although Budge's books are still widely available, our understanding of ancient Egypt has improved a lot since his time. Modern translations and dating methods are much more accurate. Also, the way scholars write today is different; they make a clear difference between opinions and proven facts. According to Egyptologist James Peter Allen, Budge's books "were not very reliable when they first came out and are now very old-fashioned."

Budge was also interested in the paranormal and believed in spirits and hauntings. He had friends in the Ghost Club, a group in London that studied ancient beliefs and the spirit world. He often told his friends funny stories about hauntings and strange experiences. Many people in his time who were interested in the occult and spiritualism found his works very important, especially his translation of the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Writers like the poet William Butler Yeats and James Joyce studied this work and were influenced by it. Budge's books on Egyptian religion have always been available since they became public domain.

Budge was a member of the Savile Club in London, a literary and open-minded club. His friend H. Rider Haggard suggested him for membership in 1889. Budge was a popular dinner guest in London because of his funny stories. He enjoyed spending time with wealthy people, many of whom he met when they brought their scarabs and statues bought in Egypt to the British Museum. Budge was always invited to country houses in the summer or fancy townhouses during the London social season.

See also

- Gebelein predynastic mummies

- Mike the cat, companion of Wallis Budge, who guarded the courtyard of the British Museum for twenty years

- List of Egyptologists

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |