Sennacherib facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sennacherib |

|

|---|---|

|

|

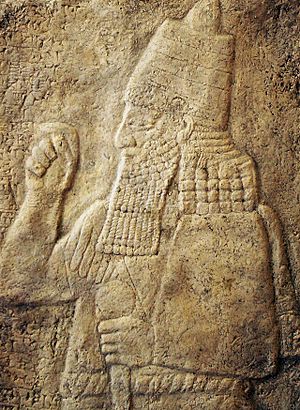

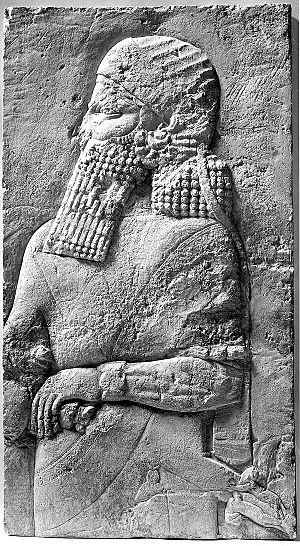

Cast of a rock relief of Sennacherib from the foot of Mount Judi, near Cizre

|

|

| King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire | |

| Reign | 705–681 BC |

| Predecessor | Sargon II |

| Successor | Esarhaddon |

| Born | c. 745 BC Nimrud (?) |

| Died | 20 October 681 BC (aged c. 64) Nineveh |

| Spouse | Tashmetu-sharrat Naqi'a |

| Issue Among others |

Ashur-nadin-shumi Arda-Mulissu Esarhaddon |

| Akkadian | Sîn-ahhī-erība Sîn-aḥḥē-erība |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Sargon II |

| Mother | Ra'īmâ |

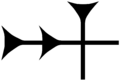

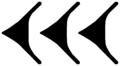

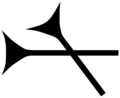

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Sîn-ahhī-erība or Sîn-aḥḥē-erība, meaning "Sîn has replaced the brothers") was a powerful king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. He ruled from 705 BC to 681 BC, taking over after his father, Sargon II, died. Sennacherib was the second king of the Sargonid dynasty.

Sîn-ahhī-erība or Sîn-aḥḥē-erība, meaning "Sîn has replaced the brothers") was a powerful king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. He ruled from 705 BC to 681 BC, taking over after his father, Sargon II, died. Sennacherib was the second king of the Sargonid dynasty.

He is well-known because his story appears in the Hebrew Bible, which talks about his military campaign in the Levant. During his rule, he also destroyed the city of Babylon in 689 BC. He also worked hard to rebuild and expand Nineveh, which became the last great capital of Assyria.

Even though Sennacherib was a very strong king, he had a lot of trouble controlling Babylonia, which was a southern part of his empire. A tribal leader named Marduk-apla-iddina II often caused problems. He had been Babylon's king before Sennacherib's father defeated him. When Sennacherib became king, Marduk-apla-iddina took Babylon back and teamed up with the Elamites.

Sennacherib fought back and took control of the south again in 700 BC. But Marduk-apla-iddina kept causing trouble, possibly encouraging other areas to rebel. This led to a big war in the Levant in 701 BC. Later, the Babylonians and Elamites captured and killed Sennacherib's oldest son, Ashur-nadin-shumi, who was ruling Babylon for his father. Because Babylon had caused so many problems and led to his son's death, Sennacherib destroyed the city in 689 BC.

In the war in the Levant, some states, especially the Kingdom of Judah under King Hezekiah, were hard to defeat. The Assyrians invaded Judah. The Bible says that an angel stopped Sennacherib's attack on Jerusalem by destroying his army. However, it's unlikely the Assyrians were completely defeated, as Hezekiah later gave in to Sennacherib. Other historical records from that time don't mention the Assyrians losing at Jerusalem.

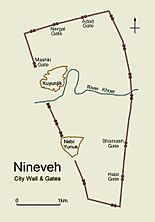

Sennacherib moved the capital of Assyria to Nineveh, where he had lived as a crown prince. He wanted to make Nineveh a grand capital, so he started huge building projects. He made the city bigger, built strong walls, many temples, and a royal garden. His most famous building was the Southwest Palace, which he called his "Palace without Rival."

After his oldest son, Ashur-nadin-shumi, died, Sennacherib first chose his second son, Arda-Mulissu, to be the next king. But in 684 BC, for reasons we don't know, he changed his mind and picked his younger son, Esarhaddon. Arda-Mulissu tried many times to get his position back, but Sennacherib ignored him. In 681 BC, Arda-Mulissu and his brother Nabu-shar-usur killed Sennacherib, hoping to become king themselves. People in Babylonia and the Levant were happy about his death, seeing it as a punishment from the gods. But in Assyria, people were likely shocked and upset. Arda-Mulissu's plan didn't work out. Esarhaddon gathered an army, took control of Nineveh, and became king, just as Sennacherib had planned.

Contents

Sennacherib's Early Life

Family and Childhood

Sennacherib was the son of Sargon II, who was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Sargon ruled Assyria from 722 to 705 BC and Babylon from 710 to 705 BC. We are not sure who Sennacherib's mother was. For a long time, people thought it was Sargon's wife Ataliya. However, it's now believed his mother was another of Sargon's wives, Ra'īmâ. A stone tablet found in 1913 clearly calls her the "mother of Sennacherib."

Sennacherib was probably born around 745 BC in a city called Nimrud. If his father Sargon was truly the son of King Tiglath-Pileser III, then Sennacherib grew up in the royal palace. Sargon lived in Nimrud for many years as king. Later, he moved to Babylon and then to his new capital, Dur-Sharrukin.

By the time Sargon moved to Babylon, Sennacherib was already living in Nineveh. Nineveh was the special home for the Assyrian crown prince, the son who would become king. Sennacherib also owned land in a place called Tarbisu. He and his brothers and sisters were taught by a royal teacher named Hunnî. They likely learned how to read, write, and do math in both Sumerian and Akkadian.

Sennacherib had several brothers and at least one sister. His name, Sîn-aḥḥē-erība, means "Sîn (the moon-god) has replaced the brothers." This probably means he wasn't Sargon's first son, but his older brothers had died before he was born. In Assyria, it was against the law to name a common person Sennacherib after he became king. This was because his name was considered very special.

As a Young Prince

As the crown prince, Sennacherib helped his father rule the empire. Sometimes, he even ruled alone when Sargon was away fighting wars. When Sargon was gone for a long time, Sennacherib's home in Nineveh became the center of the Assyrian government. He had many important jobs, showing that his father trusted him a lot.

Sennacherib's main duties included talking with Assyrian governors and generals. He also managed the empire's spy network. He kept Sargon updated on building projects and handled gifts and payments from other rulers. After giving out these resources, he would write letters to his father to explain his choices.

Letters show that Sennacherib respected his father and they were friends. He always obeyed Sargon. For some reason, Sargon never took Sennacherib with him on military campaigns. Some historians think Sennacherib might have been upset about this, as he missed out on the fame of winning battles. But Sennacherib never tried to take the throne from his father, even though he was old enough to be king.

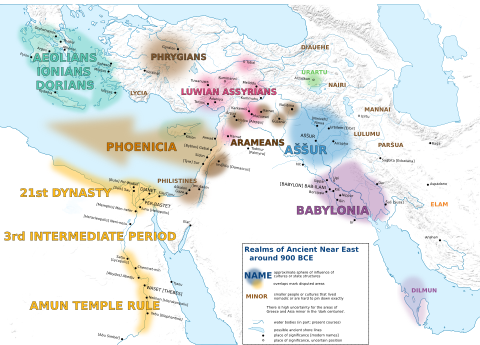

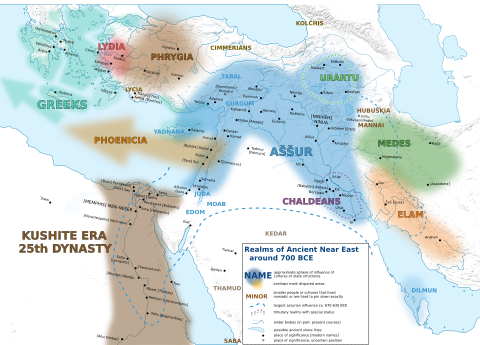

Assyria and Babylonia

By the time Sennacherib became king, the Neo-Assyrian Empire had been the strongest power in the Near East for over 30 years. This was mostly because of its large and well-trained army. Babylonia, to the south, had also been a big kingdom. But it was usually weaker than Assyria because of internal fights and a less organized army.

Babylonia had different groups of people who often disagreed. Native Babylonians lived in cities like Kish, Ur, Uruk, and Babylon itself. But Chaldean tribes, led by chiefs who often argued, controlled most of the southern land. Arameans lived on the edges and were known for raiding nearby areas. Because of these internal conflicts, Babylonia was often an easy target for Assyrian attacks.

Assyria and Babylonia had been rivals for centuries. By the 8th century BC, Assyria usually won. As Assyria grew into a huge empire, it conquered many kingdoms. Some became Assyrian provinces, while others became vassal states (meaning they had to obey Assyria). Babylon was special. Because Assyrians respected Babylon's long history and culture, it was kept as a full kingdom. It was ruled either by a local king chosen by Assyria or by the Assyrian king himself.

Assyria and Babylonia shared the same language, Akkadian. Their relationship was like a family bond; Assyrian writings sometimes called Assyria the "husband" and Babylon its "wife." One historian said, "the Assyrians were in love with Babylon, but also wished to dominate her." Babylon was seen as the source of civilization, but it was expected to stay quiet in politics. This was something Babylon often refused to do.

Sennacherib's Reign as King

Becoming King and First Challenges

In 705 BC, King Sargon II, who was probably in his sixties, led his army against King Gurdî in Anatolia. The battle was a disaster. The Assyrian army was defeated, and Sargon was killed. His body was taken away by the Anatolians. This made the defeat much worse, as Assyrians believed the gods had punished Sargon for something bad he had done.

Sennacherib was about 35 years old when he became king in August 705 BC. He had a lot of experience ruling because he had been crown prince for so long. His reaction to his father's death was to distance himself from Sargon. Sennacherib seemed to avoid thinking about what happened to Sargon. He immediately left Sargon's new capital city, Dur-Sharrukin, and moved the capital to Nineveh. One of his first acts as king was to rebuild a temple for the god Nergal, who was linked to death and war, in Tarbisu.

Sennacherib was also very religious and spent a lot of time asking his priests what Sargon might have done wrong to suffer such a fate. He wondered if Sargon had angered Babylon's gods by taking control of their city. Sennacherib also worked hard to remove images of Sargon from the empire. He raised the ground level in a temple in Assur, making Sargon's carvings invisible. Sargon is never mentioned in Sennacherib's own writings.

First War in Babylonia

After Sargon II died, many parts of the Assyrian Empire rebelled. Sargon had ruled Babylonia since 710 BC, after defeating Marduk-apla-iddina II. When Sennacherib became king, he also took the titles of both Assyria and Babylonia. But his rule in Babylonia was not as steady. Unlike previous rulers, Sennacherib called himself Babylon's king directly. He also did not perform the traditional ceremony of "taking the hand" of the Statue of Marduk, which was a way to honor Babylon's main god.

Because of this disrespect, revolts broke out in Babylonia in 704 or 703 BC. First, a man named Marduk-zakir-shumi II took the throne. But then Marduk-apla-iddina, the same leader who had fought Sargon, removed him after only a few weeks. Marduk-apla-iddina gathered many Babylonians and Chaldean tribes to fight for him. He also got soldiers from the nearby land of Elam.

Sennacherib was slow to react, which gave Marduk-apla-iddina time to place his troops in cities like Kutha and Kish. In 703 BC, Sennacherib gathered his army and attacked. His main commander first attacked near Kish but failed. However, Sennacherib realized his enemies were divided. He then led his entire army to destroy the forces at Kutha. After that, he attacked Kish and won again. Marduk-apla-iddina ran away. Sennacherib's records say he captured over 200,000 prisoners.

Sennacherib then marched to Babylon. The city surrendered without a fight. Babylon was punished with a small looting, but its people were not harmed. Sennacherib then moved through southern Babylonia, putting down all remaining resistance. Since his previous way of ruling had failed, Sennacherib tried something new. He appointed a Babylonian named Bel-ibni, who had grown up in the Assyrian palace, to be his vassal king in the south.

War in the West

After the war in Babylonia, Sennacherib's next campaign was in the Zagros Mountains. There, he defeated the Yasubigallians and the Kassites. Sennacherib's third campaign was against the kingdoms and cities in the Levant. This war is very well-known and is the most documented event in the history of Israel during the First Temple Period.

In 705 BC, Hezekiah, the king of Judah, stopped paying his yearly tribute to the Assyrians. He started to act aggressively, possibly encouraged by the rebellions happening across the empire. Hezekiah teamed up with Egypt and Sidqia, the king of Ashkelon. Hezekiah then attacked Philistine cities that were loyal to Assyria. He even captured Padi, the king of Ekron, and put him in prison in his capital, Jerusalem. In the northern Levant, cities that used to be Assyrian vassals joined Luli, the king of Tyre and Sidon. Marduk-apla-iddina, Sennacherib's old enemy, also encouraged these anti-Assyrian feelings.

In 701 BC, Sennacherib first attacked the cities in the north. Luli, like many rulers before him, ran away by boat to avoid the Assyrians. Sennacherib then made Ethbaal the new king of Sidon and his vassal. Many nearby cities quickly surrendered to Sennacherib to avoid being punished. These included Budu-ilu of Ammon, Kamusu-nadbi of Moab, Mitinti of Ashdod, and Malik-rammu of Edom.

The resistance in the southern Levant was harder to stop, so Sennacherib had to invade that area. The Assyrians first took Ashkelon and defeated Sidqia. Then they surrounded and captured many cities. As the Assyrians were getting ready to take Ekron, Hezekiah's ally, Egypt, sent help. But the Assyrians defeated the Egyptian army in a battle near Eltekeh. They then took Ekron and Timnah. Judah was left alone, and Sennacherib focused on Jerusalem.

While some of Sennacherib's troops prepared to block Jerusalem, Sennacherib himself marched on the important Judean city of Lachish. The blockade of Jerusalem and the siege of Lachish probably stopped more Egyptian help from reaching Hezekiah. It also scared the kings of other small states. The siege of Lachish lasted so long that the defenders eventually used arrowheads made of bone because they ran out of metal. To capture the city, the Assyrians built a huge ramp of earth and stone to reach the top of Lachish's walls. After destroying the city, the Assyrians sent the survivors to the Assyrian Empire. Some were forced to work on Sennacherib's building projects, and others joined his personal guard.

Sennacherib at Jerusalem's Gates

Sennacherib's own account of what happened at Jerusalem says: "As for Hezekiah... like a caged bird I shut up in Jerusalem his royal city. I barricaded him with outposts, and exit from the gate of his city I made taboo for him." This means Jerusalem was blocked off, but it probably wasn't a full siege because there wasn't enough military equipment for that. The Bible says an Assyrian official called Rabshakeh stood outside the city walls and demanded Jerusalem surrender.

Sennacherib's records might make it seem like he was there in person, but it's never clearly stated. Carvings show Sennacherib sitting on a throne in Lachish, not directing the attack on Jerusalem. The Bible says the Assyrian messengers returned to Sennacherib to find him fighting near the city of Libnah.

The way Jerusalem was blocked was different from the large sieges described in Sennacherib's records and shown in his palace carvings, which focus on the successful siege of Lachish. Even though Jerusalem wasn't fully besieged, it's clear a huge Assyrian army was camped nearby, probably on the north side.

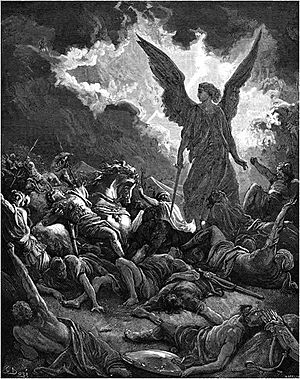

It's not clear how the blockade of Jerusalem ended without a big fight. The Bible says that while Hezekiah's soldiers were ready to defend the city, a destroying angel sent by Yahweh wiped out Sennacherib's army, killing 185,000 Assyrian soldiers outside Jerusalem's gates. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus said the Assyrians failed because "field-mice" ate their weapons, leaving them defenseless. This mouse story might mean a disease, like the septicemic plague, hit the Assyrian camp. Another idea is that an army from Egypt helped lift the blockade. It's unlikely the Assyrians were completely defeated, especially since Babylonian records, which usually like to mention Assyrian failures, don't say anything about it.

Despite the unclear end to the Jerusalem blockade, the campaign in the Levant was mostly an Assyrian victory. After the Assyrians took many of Judah's strong cities and destroyed towns, Hezekiah realized his actions against Assyria were a big mistake. He submitted to the Assyrians again. He had to pay a much higher tribute, plus a penalty for not sending tribute earlier. Sennacherib also gave large parts of Judah's land to the nearby kingdoms of Gaza, Ashdod, and Ekron.

Solving the Babylonian Problem

By 700 BC, the situation in Babylonia was bad again, and Sennacherib had to invade to regain control. Bel-ibni, the vassal king Sennacherib had appointed, was now facing rebellions from two tribal leaders: Shuzubu (who later became king as Mushezib-Marduk) and the elderly Marduk-apla-iddina. Sennacherib first removed Bel-ibni from the throne, either because he was bad at his job or because he was involved in the revolts. Bel-ibni was sent back to Assyria and is not heard from again.

The Assyrians searched for Shuzubu in the northern marshes of Babylonia but couldn't find him. Sennacherib then hunted for Marduk-apla-iddina so intensely that he and his people fled across the Persian Gulf to the Elamite city of Nagitu. Sennacherib won this fight. He then tried another way to rule Babylonia: he appointed his son Ashur-nadin-shumi as the new vassal king.

Ashur-nadin-shumi was also called māru rēštû, which could mean "pre-eminent son" or "firstborn son." Making him king of Babylon and giving him this title suggests that Ashur-nadin-shumi was being prepared to become the next king of Assyria. Assyrians usually followed the rule that the oldest son inherits the throne. Sennacherib even built a palace for Ashur-nadin-shumi in Assur, just like he would later do for Esarhaddon. Being an Assyrian king of Babylon was a very important and tricky job, and it would have given Ashur-nadin-shumi valuable experience for ruling the entire Neo-Assyrian Empire.

For the next few years, Babylonia was relatively peaceful. Sennacherib fought in other places. In 699 BC, he raided villages near Mount Judi. His generals also led smaller campaigns without him, like one in 698 BC against a revolting governor in Cilicia, and another in 695 BC against the city of Tegarama. In 694 BC, Sennacherib invaded Elam, specifically to find Marduk-apla-iddina and the other Chaldean refugees.

The Elamite War and Revenge

To attack Elam, Sennacherib built two large fleets of ships on the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. The Tigris fleet was moved overland to a canal that connected to the Euphrates. The two fleets then joined and sailed down to the Persian Gulf. A storm hit their camp at the head of the Persian Gulf, forcing the soldiers onto their ships. They then sailed across the Persian Gulf, a difficult journey that involved many sacrifices to Ea, the god of the deep.

The Assyrians successfully landed on the Elamite coast and attacked the Chaldean refugees. Both Babylonian and Assyrian records say this went well for the Assyrians. Sennacherib's accounts describe it as a "great victory" and list several cities they captured and looted. Sennacherib finally got his revenge on Marduk-apla-iddina, but his old enemy had already died of natural causes before the Assyrians arrived.

The war then took an unexpected turn. The king of Elam, Hallutash-Inshushinak I, took advantage of the Assyrian army being far away. He invaded Babylonia. With help from surviving Chaldean troops, Hallutash-Inshushinak captured the city of Sippar. There, he also captured Ashur-nadin-shumi, Sennacherib's son, and took him back to Elam. Ashur-nadin-shumi was never heard from again and was likely killed. In his place, a Babylonian named Nergal-ushezib became Babylon's king.

The Assyrian army, now surrounded by Elamites in southern Babylonia, managed to kill Hallutash-Inshushinak's son in a small fight but remained trapped for at least nine months. Nergal-ushezib, wanting to secure his power, captured and looted the city of Nippur. Some months later, the Assyrians attacked and captured the southern city of Uruk. Nergal-ushezib was scared and asked the Elamites for help. Just seven days after taking Uruk, the Assyrians and Babylonians fought near Nippur. The Assyrians won a huge victory, defeating the Elamite-Babylonian army and capturing Nergal-ushezib. The Assyrian army was finally free from being trapped in the south. Sennacherib had managed to slip past the enemy forces earlier and was not present at this final battle. He was probably on his way from Assyria with more troops. By the time he rejoined his army, the war with Babylonia was already won.

Soon after, a revolt broke out in Elam. Hallutash-Inshushinak was removed from power, and Kutur-Nahhunte became king. Sennacherib was determined to end the threat from Elam. He retook the city of Der, which Elam had occupied, and moved into northern Elam. Kutur-Nahhunte couldn't organize a good defense and ran away to a mountain city. Soon after, bad weather forced Sennacherib to go back home.

The Destruction of Babylon

Even though Nergal-ushezib was defeated and the Elamites fled, Babylonia did not surrender to Sennacherib. The rebel Shuzubu, whom Sennacherib had hunted in 700 BC, reappeared as Mushezib-Marduk and became king of Babylon. He seemed to have no foreign support at first. It's possible Sennacherib accepted his rule for a short time. There was also a change in Elam, where Kutur-Nahhunte was replaced by Humban-menanu. Humban-menanu started to gather an anti-Assyrian alliance again. Mushezib-Marduk got Humban-menanu's support by paying him. Assyrian records thought Humban-menanu's decision to help Babylonia was foolish.

Sennacherib fought his enemies near the city of Halule. Humban-menanu and his commander, Humban-undasha, led the Babylonian and Elamite forces. The result of the Battle of Halule is not clear, as both sides claimed a great victory. Sennacherib said Humban-undasha was killed and the enemy kings ran away. But Babylonian records said the Assyrians retreated. If the Babylonians won, it must have been a small victory, because Babylon was under siege by late summer 690 BC.

In 690 BC, Humban-menanu had a stroke and couldn't speak. Sennacherib used this chance to start his final campaign against Babylon. The Babylonians had some early success, but it didn't last. By the same year, the siege of Babylon was well underway. Babylon was likely in a very bad state when it fell to Sennacherib in 689 BC, after being under siege for over 15 months.

Sennacherib had once worried about his father taking Babylon and how it might have angered the city's gods. But by 689 BC, his feelings had changed. He decided to destroy Babylon. Some historians believe Sennacherib wanted to get revenge for his son's death and was tired of a city within his own empire constantly rebelling. He might have felt that Babylon's gods had encouraged their people to attack him. Sennacherib's own account of the destruction says:

Into my land I carried off alive Mušēzib-Marduk, king of Babylonia, together with his family and officials. I counted out the wealth of that city—silver, gold, precious stones, property and goods—into the hands of my people; and they took it as their own. The hands of my people laid hold of the gods dwelling there and smashed them; they took their property and goods.

I destroyed the city and its houses, from foundation to parapet; I devastated and burned them. I razed the brick and earthenwork of the outer and inner wall of the city, of the temples, and of the ziggurat; and I dumped these into the Araḫtu canal. I dug canals through the midst of that city, I overwhelmed it with water, I made its very foundations disappear, and I destroyed it more completely than a devastating flood. So that it might be impossible in future days to recognize the site of that city and its temples, I utterly dissolved it with water and made it like inundated land.

Even though he destroyed the city, Sennacherib still seemed a bit afraid of Babylon's ancient gods. He mentioned that the temples of the Babylonian gods had given money to his enemies. When he described taking the gods' property and destroying some statues, he used "my people" instead of "I." This might mean he wanted to put the blame for the temples' fate on the temple staff and the Assyrian people, not just himself.

During the destruction, Sennacherib destroyed temples and images of gods, except for Marduk's statue, which he took to Assyria. This upset people in Assyria, who respected Babylon and its gods. Sennacherib tried to explain his actions to his own people through religious messages. He even created a story where Marduk was put on trial before Ashur, the god of Assyria, and found guilty. Sennacherib described his defeat of the Babylonian rebels using the language of the Babylonian creation myth, comparing Babylon to an evil demon-goddess and himself to Marduk. Ashur replaced Marduk in the New Year's festival, and Sennacherib placed a symbolic pile of rubble from Babylon in the festival temple. In Babylonia, Sennacherib's actions created a deep hatred among the people.

Sennacherib wanted to completely erase Babylonia as a separate country. Some northern Babylonian areas became Assyrian provinces. But the Assyrians didn't try to rebuild Babylon itself. Records from that time in the south call it the "kingless" period, meaning there was no king in the land.

Rebuilding Nineveh

After the final war with Babylon, Sennacherib spent his time improving his new capital, Nineveh. He didn't go on many big military campaigns. Nineveh had been an important city for thousands of years. When Sennacherib made it his capital, he started one of the most ambitious building projects in ancient history. He completely changed the city, which had been a bit neglected before his rule. His father's new capital, Dur-Sharrukin, was just like the old capital, Nimrud. But Sennacherib wanted Nineveh to be so grand that it would amaze the whole world.

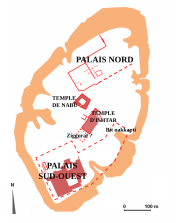

The first writings about the Nineveh building project are from 702 BC. They talk about building the Southwest Palace, a huge home in the southwestern part of the city's fortress. Sennacherib called this palace the ekallu ša šānina la išu, meaning "Palace without Rival." During construction, a smaller palace was torn down. A stream that was eroding the palace mound was moved, and a high platform was built for the new palace. Even though early writings made it sound like the palace was finished, this was a common way to write about building projects in ancient Assyria. The Nineveh described in Sennacherib's early accounts was a city that only existed in his mind at that point.

By 700 BC, the walls of the Southwest Palace's throne room were being built, followed by many carvings to decorate it. The last step was putting up huge statues of bulls and lions, which were common in Assyrian buildings. Some stone statues have been found, but the huge statues made of precious metals mentioned in the writings are still missing. The palace roof was made from cypress and cedar wood brought from western mountains. The palace had many windows and was decorated with silver and bronze pegs inside and shiny bricks outside. The whole building, based on its platform, was 450 meters long and 220 meters wide. A writing on a stone lion in the area of Sennacherib's queen, Tashmetu-sharrat, wishes that the king and queen would live long and healthy lives in the new palace. The writing is very personal and says:

And for the queen Tashmetu-sharrat, my beloved wife, whose features Belet-ili has made more beautiful than all other women, I had a palace of love, joy and pleasure built. [...] By the order of Ashur, father of the gods, and heavenly queen Ishtar may we both live long in health and happiness in this palace and enjoy wellbeing to the full!

Sennacherib's palace and its artwork were different from his father Sargon's palace. Sargon's carvings usually showed the king close to other important Assyrians. But Sennacherib's art often showed him much taller than everyone else, riding in a chariot. His carvings showed bigger scenes, sometimes from a high-up view. The art also looked more realistic. For example, Sargon's huge bull statues had five legs so that four could be seen from any side. Sennacherib's bulls all had four legs.

Sennacherib built beautiful gardens at his new palace. He brought in many different plants and herbs from all over his empire and beyond. Even Cotton plants might have come from as far away as India. Some people think the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, were actually these gardens in Nineveh. However, one historian thinks this is unlikely because Babylon itself had impressive royal gardens.

Besides the palace, Sennacherib worked on other building projects in Nineveh. He built a large second palace on the city's southern mound. This palace was used as a storage place for military equipment and as living quarters for part of the Assyrian army. Many temples were built and repaired, especially on the Kuyunjik mound (where the Southwest Palace was). This included a temple for the god Sîn, whose name was part of the king's own name. Sennacherib also greatly expanded the city to the south and built huge new city walls, surrounded by a moat. These walls were up to 25 meters high and 15 meters thick.

Plot, Murder, and New King

When his oldest son and first chosen heir, Ashur-nadin-shumi, disappeared (likely killed), Sennacherib chose his oldest living son, Arda-Mulissu, to be the new crown prince. Arda-Mulissu held this important position for several years. But in 684 BC, Sennacherib suddenly replaced him with his younger brother, Esarhaddon. We don't know why Arda-Mulissu was removed, but he was very disappointed. Esarhaddon's powerful mother, Naqi'a, might have helped convince Sennacherib to choose Esarhaddon. Even after being removed, Arda-Mulissu remained popular, and some leaders secretly supported him.

Sennacherib made Arda-Mulissu promise loyalty to Esarhaddon. But Arda-Mulissu kept asking his father to make him heir again. Sennacherib noticed Arda-Mulissu's growing popularity and worried about Esarhaddon. So, he sent Esarhaddon to the western provinces. Esarhaddon's absence put Arda-Mulissu in a difficult spot. He was popular but couldn't do anything to his brother. To take advantage of the situation, Arda-Mulissu decided he had to act fast and take the throne by force. He made a secret agreement with another younger brother, Nabu-shar-usur. On October 20, 681 BC, they attacked and killed their father in one of Nineveh's temples, possibly the one dedicated to Sîn.

The murder of Sennacherib, the ruler of one of the world's strongest empires, shocked everyone at the time. People across the Near East reacted with strong and mixed feelings. People in the Levant and Babylonia celebrated, saying it was a punishment from the gods for Sennacherib's harsh wars against them. But in Assyria, people were likely upset and horrified. Many historical sources recorded the event, including the Bible, where Arda-Mulissu is called Adrammelech.

Even though their plot succeeded, Arda-Mulissu couldn't become king. The murder made some of his own supporters turn against him, which delayed his crowning. Meanwhile, Esarhaddon had gathered an army. The armies of Arda-Mulissu and Nabu-shar-usur met Esarhaddon's forces in Hanigalbat, a western part of the empire. There, most of their soldiers left and joined Esarhaddon. Esarhaddon then marched on Nineveh without anyone stopping him and became the new king of Assyria. Soon after becoming king, Esarhaddon executed all the people who had plotted against his father and other political enemies, including his brothers' families. Every servant who was supposed to guard the royal palace in Nineveh was also killed. Arda-Mulissu and Nabu-shar-usur survived this purge and escaped as exiles to the northern kingdom of Urartu.

Family and Children

Like other Assyrian kings, Sennacherib had many wives. We know the names of two of his wives: Tashmetu-sharrat (Tašmetu-šarrat) and Naqi'a (Naqiʾā). It's not clear if both were queens at the same time. Historical records suggest that even if a king had many wives, usually only one was recognized as the main queen. For most of Sennacherib's reign, the queen was Tashmetu-sharrat, whose name means "Tashmetum is queen." Writings suggest Sennacherib and Tashmetu-sharrat had a loving relationship. The king called her "my beloved wife" and praised her beauty.

It's unclear if Naqi'a was ever officially queen. She was called the "queen mother" during Esarhaddon's reign. Since she was Esarhaddon's mother, she might have received this title late in Sennacherib's reign or from Esarhaddon himself. Even though Tashmetu-sharrat was queen for longer, Naqi'a is more famous today because of her role during Esarhaddon's rule. When she became one of Sennacherib's wives, she took the Akkadian name Zakûtu (Naqi'a is an Aramaic name). Having two names might mean Naqi'a was born outside Assyria, perhaps in Babylonia or the Levant, but there's no strong proof for this.

Sennacherib had at least seven sons and one daughter. We only know that Esarhaddon was Naqi'a's son. We don't know which of Sennacherib's wives were the mothers of his other children. Tashmetu-sharrat was likely the mother of at least some of them. Their names were:

- Ashur-nadin-shumi (Aššur-nādin-šumi) – Probably Sennacherib's oldest son. He was made king of Babylon and crown prince in 700 BC. He ruled until he was captured and killed by the Elamites in 694 BC.

- Ashur-ili-muballissu (Aššur-ili-muballissu) – Likely Sennacherib's second oldest son. He is mentioned as having a role in the priesthood. His father gave him a house in Assur and a valuable vase.

- Arda-Mulissu (Arda-Mulišši) – Sennacherib's oldest living son after Ashur-nadin-shumi died. He was crown prince from 694 BC until 684 BC. For unknown reasons, he was replaced by Esarhaddon. He planned Sennacherib's murder in 681 BC to take the throne. After his troops were defeated, he escaped to Urartu.

- Ashur-shumu-ushabshi (Aššur-šumu-ušabši) – His place among Sennacherib's children is unknown. Sennacherib gave him a house in Nineveh. Bricks found there suggest he might have died before the house was finished.

- Esarhaddon (Aššur-aḫa-iddina) – A younger son who was crown prince from 684–681 BC. He became king of Assyria after Sennacherib's death, ruling from 681 to 669 BC.

- Nergal-shumu-ibni (Nergal-šumu-ibni) – The name of another son, though parts of his name are missing in records. He had many servants. He might have been crown prince alongside Arda-Mulissu, possibly meant to rule Babylonia, but this is not certain.

- Nabu-shar-usur (Nabû-šarru-uṣur) – A younger son who joined Arda-Mulissu in the plot to kill Sennacherib and take power. He escaped with Arda-Mulissu to Urartu.

- Shadditu (Šadditu) – Sennacherib's only known daughter by name. She is mentioned in land sale documents. She was likely Naqi'a's daughter, as she remained part of the royal family during Esarhaddon's reign. She or another daughter married an Egyptian noble in 672 BC.

A small tablet found in Nineveh lists names of ancient heroes and some personal names. Since Ashur-ili-muballissu's name is on it, along with names that might be Ashur-nadin-shumi and Esarhaddon, it's possible the other names on the list were also Sennacherib's sons.

Sennacherib's Character

We learn about Sennacherib's personality mostly from his royal inscriptions. These were written by his scribes and were like propaganda, making the king seem better than all other rulers. Assyrian royal writings usually only talk about wars and building projects and are very similar from king to king. But by looking closely at Sennacherib's writings and comparing them, we can guess some things about him.

Like other Assyrian kings, his writings show pride and high self-esteem. For example, he wrote: "Ashur, father of the gods, looked steadfastly upon me among all the rulers and he made my weapons greater than (those of) all who sit on (royal) daises." His great intelligence is often mentioned, like in the line: "the god Ninshiku gave me wide understanding equal to (that of) the sage Adapu (and) endowed me with broad knowledge." Many writings call him "foremost of all rulers" and a "perfect man."

Sennacherib chose to keep his birth name when he became king, which was unusual. Most kings took a new throne name. This suggests he was very confident. He also used new titles never used by other Assyrian kings, like "guardian of the right" and "lover of justice." This shows he wanted to make his own mark on the empire.

When Sennacherib became king, he was already an adult and had served as crown prince for over 15 years. He understood how the empire worked. Unlike many kings before and after him, Sennacherib didn't present himself as a conqueror who wanted to take over the whole world. Instead, his writings often focused on his huge building projects as the most important parts of his rule. Most of his military campaigns were not about conquering new lands. They were about stopping rebellions, getting back lost areas, and finding treasure to pay for his building projects. The fact that his generals led some campaigns, not the king himself, shows he wasn't as interested in fighting as earlier kings. The harsh punishments described in his records for Assyria's enemies might not always be exactly true. They also served as a way to scare people and spread propaganda.

Even though he didn't seem interested in world domination, Sennacherib used the traditional titles that meant he ruled the whole world: "king of the universe" and "king of the four corners of the world." Other titles, like "strong king" and "mighty king," showed his power. He also used descriptions like "virile warrior" and "fierce wild bull." Sennacherib described all his campaigns, even the ones that weren't successful, as victories in his own accounts. This was important because his people would see a failed campaign as a sign that the gods no longer supported him. Sennacherib truly believed the gods supported him and thought all his wars were right for this reason.

Some historians think Sennacherib might have suffered from stress because of his father's terrible death. It seems that bad news easily made Sennacherib angry, and he might have developed serious emotional problems. His son Esarhaddon later wrote that a "demon" affected Sennacherib, and none of his priests dared to tell the king they saw signs of this demon.

One historian believes Sennacherib might have been a "feminist" in some ways. Female members of the royal court had more power and privileges during his reign than under previous kings. We don't know why he treated his female relatives this way. He might have wanted to shift power away from powerful generals to his own family. He might also have been influenced by strong Arab queens who made their own decisions and led armies. There are more writings about Assyrian queens from Sennacherib's time, and there's proof that his queens had their own military units, just like the king. Female gods were also shown more often during Sennacherib's time.

Despite his religious beliefs and fear about his father's fate, some historians think Sennacherib might have been a bit skeptical about religion. His destruction of Babylon, including its temples, was a very disrespectful act. He also seemed to ignore temples in Assyria until he rebuilt the temple of Ashur late in his reign.

Sennacherib's Legacy

How People Remembered Him

For thousands of years after Sennacherib's death, people mostly saw him in a bad light. This was mainly because of two reasons: first, the Bible shows him as an evil conqueror who tried to take Jerusalem; second, he destroyed Babylon, one of the most famous ancient cities. This negative view of Sennacherib continued until modern times. He was often seen as a cruel attacker, like a "wolf on the fold" in the famous 1815 poem The Destruction of Sennacherib by Lord Byron:

The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold,

And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold;

And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea,

When the blue wave rolls nightly on deep Galilee.—Lord Byron (1815), first stanza.

Historians say Sennacherib's attack on Jerusalem in 701 BC was a "world event." It brought together the fates of many different groups. It affected Assyrians, Israelites, Babylonians, Egyptians, Nubians, and others. This event is talked about not only in old records but also in later stories and traditions. These include Aramaic folklore, ancient Greek and Roman histories, and tales from medieval Syriac Christians and Arabs.

Sennacherib's campaign in the Levant is a very important event in the Bible. It's mentioned in many places, especially in 2 Kings and 2 Chronicles. A large part of the Bible's account of King Hezekiah's rule is about Sennacherib's campaign, making it the most important event of Hezekiah's time. In Chronicles, the story focuses on Sennacherib's failure and Hezekiah's success. The Assyrian campaign is shown as an act of aggression that was meant to fail from the start. The story says that no enemy, not even the powerful king of Assyria, could defeat Hezekiah because the Judean king had God on his side. The conflict is shown as a holy war: God's war against the pagan Sennacherib.

Even though Assyria had over a hundred kings, Sennacherib (along with his son Esarhaddon and grandsons Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin) was one of the few kings remembered in Aramaic and Syriac stories long after the empire fell. An old Aramaic story, the story of Ahikar, shows Sennacherib as a kind supporter of Ahikar, while Esarhaddon is shown more negatively. Medieval Syriac stories describe Sennacherib as a typical pagan king who was killed in a family fight, and whose children later became Christians. The legend of the 4th-century Saints Behnam and Sarah says Sennacherib, called Sinharib, was their royal father. After Behnam became Christian, Sinharib ordered him to be killed. But later, Sinharib got a dangerous disease that was cured when he was baptized by Saint Matthew. Grateful, Sinharib then became Christian and built an important monastery near Mosul.

Sennacherib also plays different roles in later Jewish traditions. In Midrash, which are studies of the Old Testament and later stories, the events of 701 BC are often explored in detail. These stories often describe huge armies sent by Sennacherib and how he kept asking astrologers for advice, which delayed his actions. In these stories, Sennacherib's armies are destroyed when Hezekiah recites special psalms on the night before Passover. The event is often shown as an apocalyptic scenario, with Hezekiah as a messianic figure and Sennacherib and his armies representing evil forces. Because of his role in the Bible, Sennacherib remains one of the most famous Assyrian kings today.

Discoveries by Archaeologists

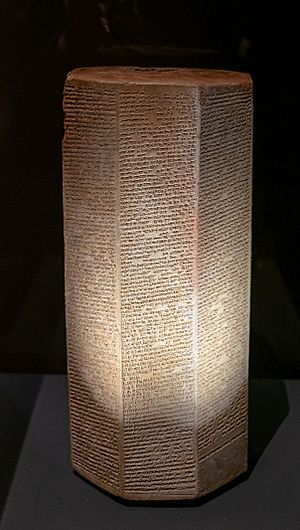

When Sennacherib's own writings were found in the 19th century, his already fierce reputation grew even more. Today, many of his writings are known. Most are kept in museums like the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin and the British Museum in London. Some large objects with Sennacherib's writings are still in Nineveh, and some have even been reburied. Sennacherib's own accounts of his building projects and military campaigns, called his "annals," were often copied many times and shared throughout the Neo-Assyrian Empire during his rule. For the first six years of his reign, they were written on clay cylinders. Later, he started using clay prisms, probably because they had more space for writing.

Fewer letters from Sennacherib's time have been found compared to those from his father's time or his son Esarhaddon's time. Most of the letters we have are from when Sennacherib was crown prince. Other types of writings from his reign, like administrative and economic documents, are more common.

Besides written records, many artworks from Sennacherib's time have survived. These include the king's carvings from his palace in Nineveh. They usually show his conquests, sometimes with short texts explaining the scene. The British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard first found and dug up these carvings from 1847 to 1851. The discovery of carvings showing Sennacherib's siege of Lachish in the Southwest Palace was the first time an event described in the Bible was confirmed by archaeology.

Other archaeologists continued to dig at the Southwest Palace. Among the many writings found, George Smith discovered a broken account of a great flood, which caused a lot of excitement. Since Smith's time, the site has been dug up and studied many times. Many of Sennacherib's carvings are now shown in museums around the world.

The old negative view of Sennacherib as a cruel conqueror has changed in modern studies. Historians now see Sennacherib as a king who was open-minded and thought ahead. He handled problems well and even used them to create a stable empire. Some believe the Assyrian Empire's collapse within 70 years of Sennacherib's death was partly because later kings ignored his ideas and changes. Another historian concluded that Sennacherib was different from both the traditional negative image and the perfect image he wanted to show. She believes Sennacherib was "certainly intelligent, skillful, with an ability of adaptation," but his religious beliefs were "contradictory." He destroyed gods' statues and temples in Babylon but also consulted and prayed to gods before acting. She thinks Sennacherib's biggest flaw was his "irascible, vindictive and impatient character," meaning he could be easily angered, seek revenge, and make quick, emotional decisions.

In 2011, a huge slope with a multi-step staircase was found in Erbil. A cuneiform text on one of the bricks mentioned King Sennacherib's name. During French excavations, many other cuneiform inscriptions were found. Most of them mention one of the king's titles and talk about building a wall and a palace in the city.

Titles of Sennacherib

Sennacherib used many grand titles. Here are some examples from his early writings about his campaign in Babylonia in 703 BC:

Sennacherib, great king, mighty king, king of Assyria, king without rival, righteous shepherd, favorite of the great gods, prayerful shepherd, who fears the great gods, protector of righteousness, lover of justice, who lends support, who comes to the aid of the cripple and aims to do good deeds, perfect hero, mighty man, first among all kings, neckstock that bends the insubmissive, who strikes the enemy like a thunderbolt, Ashur, the great mountain, has bestowed upon me an unrivalled kingship and has made my weapons mightier than the weapons of all other rulers sitting on daises.

This version of his titles was used in a writing from the Southwest Palace in Nineveh after his Babylonian campaign in 700 BC:

Sennacherib, the great king, the mighty king, king of the universe, king of Assyria, king of the four quarters (of the world); favorite of the great gods; the wise and crafty one; strong hero, first among all princes; the flame that consumes the insubmissive, who strikes the wicked with the thunderbolt. Assur, the great god, has intrusted to me an unrivaled kingship, and has made powerful my weapons above (all) those who dwell in palaces. From the upper sea of the setting sun to the lower sea of the rising sun, all princes of the four quarters (of the world) he has brought in submission to my feet.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Senaquerib para niños

In Spanish: Senaquerib para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |