Sargon II facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sargon II |

|

|---|---|

|

|

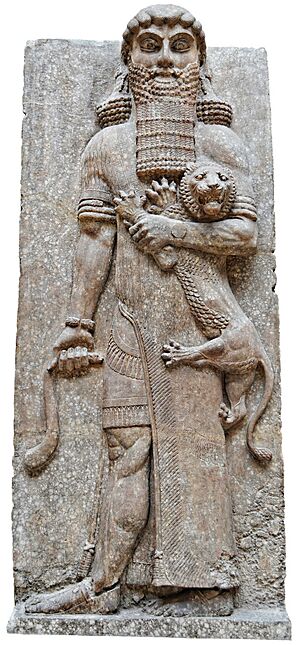

Alabaster bas-relief depicting Sargon II, from his palace in Dur-Sharrukin

|

|

| King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire | |

| Reign | 722–705 BC |

| Predecessor | Shalmaneser V |

| Successor | Sennacherib |

| Born | c. 770–760 BC |

| Died | 705 BC (aged c. 55–65) Tabal (modern-day Turkey) |

| Spouse | Ra'īmâ Atalia |

| Issue | Sennacherib Ahat-abisha At least four others |

| Akkadian | Šarru-kīn |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Tiglath-Pileser III (?) |

| Mother | Iaba (?) |

Sargon II (whose name in the ancient Akkadian meant "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was a powerful ruler of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. He was king from 722 BC until he died in battle in 705 BC.

Sargon was likely the son of Tiglath-Pileser III, a previous Assyrian king. Many historians believe Sargon became king by taking the throne from Shalmaneser V, who was probably his brother. Sargon is often seen as the founder of a new royal family line, called the Sargonid dynasty.

Sargon wanted to be like ancient rulers such as Sargon of Akkad and Gilgamesh. He dreamed of conquering the known world and bringing about a "golden age." During his 17 years as king, Sargon greatly expanded Assyrian lands. He also made important changes to the government and the army. Sargon was a skilled warrior and military planner. He personally led his soldiers into battles. By the end of his rule, most of his main enemies were defeated.

Some of Sargon's biggest achievements included making sure Assyria controlled the Levant (an area in the Middle East). He also weakened the northern kingdom of Urartu and took back control of Babylonia. From 717 BC to 707 BC, Sargon built a new capital city named after himself, Dur-Sharrukin (meaning 'Fort Sargon'). He made it his official home in 706 BC.

Sargon believed he was chosen by the gods to ensure fairness and justice. Like other Assyrian kings, he sometimes used strict punishments against his enemies. However, there are no known stories of him harming regular people. He worked to include conquered people into his empire. He gave them the same rights and duties as native Assyrians. Sargon also forgave defeated enemies many times. He kept good relationships with foreign kings and leaders in the lands he conquered. He also gave more power and importance to women and scribes in his royal court.

In 705 BC, Sargon went on his last military trip to Tabal in Anatolia. He was killed in battle. The Assyrian army could not get his body back, so he could not have a traditional burial. Ancient beliefs said that without a proper burial, his spirit would wander forever. Sargon's death was a big shock for the Assyrians and hurt his reputation. His son, Sennacherib, was very upset and thought his father must have done something very wrong. Because of this, Sennacherib tried to distance himself from Sargon. Sargon was rarely mentioned in later writings and was almost completely forgotten. This changed when the ruins of Dur-Sharrukin were found in the 1800s. He was not fully recognized as a real king by historians until the 1860s. Today, Sargon is seen as one of the most important Assyrian kings because of his conquests and changes.

Contents

Sargon's Early Life and Becoming King

From Humble Beginnings to the Throne

We do not know much about Sargon II's life before he became king. He was probably born around 770 BC, or no later than 760 BC. Before Sargon, Tiglath-Pileser III and his son Shalmaneser V ruled. Even though Sargon started a new royal family, the Sargonid dynasty, he was likely related to the old ruling family.

Sargon grew up during a tough time for the Neo-Assyrian Empire. There were many rebellions and diseases. Assyria's power had greatly decreased. But things got better under Tiglath-Pileser. He reduced the power of officials, improved the army, and made the empire much bigger. Not much is known about Shalmaneser's short rule.

Kings usually talked about their family history in their writings. But Sargon said that the Assyrian god Ashur had chosen him to be king. In only two known writings, Sargon called himself Tiglath-Pileser's son. He also mentioned his "royal fathers." Most historians think Sargon was Tiglath-Pileser's son but not the rightful heir after Shalmaneser. If he was Tiglath-Pileser's son, his mother might have been Queen Iaba.

Some historians think Sargon came from a different branch of the royal family. This branch might have been from the western part of the empire. In Babylonia, Sargon and his successors were called part of the "dynasty of Hanigalbat" (a western area). Earlier Assyrian kings were called part of the "dynasty of Baltil" (the oldest part of the capital city, Assur).

The Babylonian Chronicles say that Shalmaneser died in January 722 BC. Sargon became king in the same month. He was between 40 and 50 years old. We are not sure exactly how he became king. Some historians believe Sargon became king legally. But most scholars think he took the throne by force. One idea is that Sargon killed Shalmaneser and took power in a palace coup. Sargon rarely mentioned the kings before him. When he became king, he faced a lot of opposition within Assyria. Shalmaneser probably had sons who could have become king.

Sargon did not blame Shalmaneser for all the problems in Assur. He wrote that many of these problems started long ago. Tiglath-Pileser, not Shalmaneser, had forced people in Assur to work for the state. Sargon changed several of Shalmaneser's policies. For example, Hullî, a king in Tabal who Shalmaneser had removed, was put back on his throne by Sargon. Sargon also reversed Shalmaneser's efforts to reduce trade with Egypt.

Why Sargon Chose His Name

Sargon II was the first king in over a thousand years to use the name Sargon. Before him, there were two other Mesopotamian kings with the same name. One was Sargon I, a minor Assyrian king from the 19th century BC. The other was the very famous Sargon of Akkad from the 24th–23rd century BC. Sargon of Akkad conquered large parts of Mesopotamia and founded the Akkadian Empire.

Sargon II likely chose "Sargon" as his regnal name (a special name taken by a ruler). In ancient Mesopotamia, royal names were chosen carefully. They set the tone for a king's rule. Sargon II probably chose the name because of Sargon of Akkad. In later Assyrian texts, the names of Sargon II and Sargon of Akkad are written the same way. Sargon II is sometimes even called the "second Sargon." Even though people had forgotten the exact details of the ancient Sargon's conquests, he was still remembered as a "conqueror of the world." Sargon II also worked hard to expand his own empire.

Besides the historical connection, Sargon linked his name to justice. His name, Šarru-kīn, is often understood to mean "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king." This might have been chosen because Sargon was not the rightful heir to the throne. The ancient Sargon of Akkad also became king by taking power. The modern version of the name, Sargon, probably comes from the spelling in the Hebrew Bible.

Sargon's Reign

Early Challenges and Rebellions

Sargon's rule started with a lot of resistance in the heart of Assyria. These problems were quickly stopped. But this instability caused some distant regions to become independent again. In early 721 BC, Marduk-apla-iddina II, a Chaldean leader, took control of Babylon. He brought back Babylonian independence after eight years of Assyrian rule. He also made an alliance with the eastern kingdom of Elam. Sargon thought Marduk-apla-iddina taking Babylonia was unacceptable. However, Sargon's attempt to defeat him in battle near Der in 720 BC failed.

At the same time, Yahu-Bihdi of Hama in Syria gathered several smaller states in the northern Levant. They wanted to fight against Assyrian rule. Sargon also had to deal with conflicts left over from Shalmaneser's rule. Around the 720s BC, the Assyrians captured Samaria after a long siege. This ended the Kingdom of Israel. Sargon claimed he conquered the city. But it is more likely that Shalmaneser captured it. Both the Babylonian Chronicles and the Hebrew Bible say Israel's fall was a key event of Shalmaneser's reign. Sargon might have claimed it because the city was captured again after Yahu-Bihdi's revolt.

Either Shalmaneser or Sargon ordered the people of Samaria to be moved across the Assyrian Empire. This was a common Assyrian policy. This specific move led to the loss of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Sargon said in his writings that he moved 27,280 Israelites. While this was likely upsetting for the people, Assyrians valued these moved people for their work. They were generally treated well and moved safely with their families and belongings.

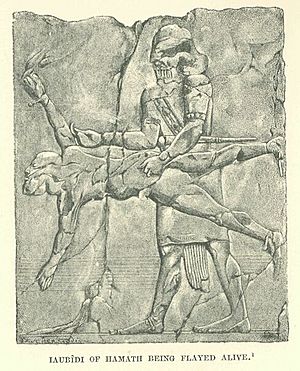

Soon after failing to take back Babylonia in 720 BC, Sargon fought against Yahu-Bihdi. Yahu-Bihdi's supporters included the cities of Arpad, Damascus, Sumur, and Samaria. Three of these cities were not vassal states; their lands had become Assyrian provinces. The revolt threatened to undo the Assyrian system in Syria. The rebels killed all local Assyrians they could find.

Sargon fought Yahu-Bihdi and his allies at Qarqar on the Orontes. Yahu-Bihdi was defeated and fled into Qarqar. Sargon besieged and captured the city. Sargon's army destroyed Qarqar and the surrounding lands. Yahu-Bihdi was first sent to Assyria with his family. Then, he was harshly punished. Hama and the other rebel cities were taken back by Assyria. Many people from Syria were moved to other parts of the empire. Sargon also moved some people to Syria, including 6,300 "guilty Assyrians." These were likely Assyrians who had fought against Sargon when he became king but were spared. Sargon called their resettlement an act of mercy.

Around the same time, Hanunu of Gaza in the south also rebelled. After defeating Yahu-Bihdi, Sargon marched south. He captured other cities, likely including Ekron and Gibbethon. The Assyrians defeated Hanunu, whose army had help from Egypt, at Rafah. Despite the rebellion, Gaza remained a semi-independent vassal state. This was perhaps because its location, near Egypt, was very important strategically.

Dealing with Rivals and Smaller Conflicts

A major concern for Sargon was the kingdom of Urartu in the north. Urartu was not as strong as it once was, but it was still a rival to Assyria. Many smaller northern states looked to Urartu for leadership. In 718 BC, Sargon got involved in Mannea, one of these states. This was both a military and a diplomatic effort. King Iranzu of Mannea had been an Assyrian ally for over 25 years. He asked Sargon for help. A rebellion by the Urartu-backed noble Mitatti had taken half of Iranzu's kingdom. But Sargon helped put down Mitatti's uprising.

Soon after this victory, Iranzu died. Sargon helped Iranzu's son, Aza, become king of Mannea. Another son, Ullusunu, challenged his brother. He was supported by Rusa I of Urartu in his efforts.

Another important enemy of Sargon was the powerful King Midas of Phrygia in central Anatolia. Sargon worried about a possible alliance between Phrygia and Urartu. He also worried about Midas using other groups to cause rebellions among Assyrian allies. Sargon could not fight Midas directly. Instead, he had to deal with uprisings by his allies among the Syro-Hittite states. Most of these were in remote mountain areas. It was vital to control the regions of Tabal and Quwê. This would stop Midas and Rusa from communicating. Tabal was especially important because it had many natural resources like silver.

Sargon campaigned against Tabal in 718 BC. He mostly fought against Kiakki of Shinuhtu, who had stopped paying tribute and was working with Midas. Sargon could not conquer Tabal because it was isolated and had difficult terrain. Instead, Shinuhtu was given to a rival Tabalian ruler, Kurtî of Atunna. Kurtî later worked with Midas but then stayed loyal to Sargon.

Sargon returned to Syria in 717 BC to defeat an uprising led by Pisiri of Carchemish. Pisiri had supported Sargon before but was now plotting with Midas to overthrow Assyrian power. The uprising was defeated. The people of Carchemish were moved, and Assyrians replaced them. The city and its lands became an Assyrian province. An Assyrian palace was built there. This conquest might have inspired Sargon to build his own new capital city, Dur-Sharrukin. He could pay for it with the silver taken from Carchemish. Sargon took so much silver that it started to replace copper as the main money in the empire. Even with Sargon's many victories in the west, the Levant was not completely stable.

In 716 BC, Sargon set up a new trading post near the Egyptian border. He staffed it with people moved from conquered lands. He placed it under the local Arab ruler Laban, an Assyrian ally. In later writings, Sargon falsely claimed he had also conquered Egypt that year. In reality, Sargon had diplomatic talks with Pharaoh Osorkon IV, who gave Sargon twelve horses as a gift.

In 716 BC, Sargon campaigned between Urartu and Elam. This was likely part of a plan to weaken these enemies. Passing through Mannea, Sargon attacked Media. He probably wanted to control this area and remove it as a threat before facing Urartu or Elam. The local Medes were not united and were not a serious threat to Assyria. After Sargon defeated them and set up Assyrian provinces, he let the local lords continue to rule their cities as allies. Replacing them and fully integrating the lands would have been too costly and time-consuming due to their distance.

As part of this eastern campaign, Sargon defeated some local rebels. These included Bag-dati of Uishdish and Bel-sharru-usur of Kisheshim. In Mannea, Ullusunu had taken the throne from his brother Aza. Instead of removing Ullusunu, Sargon accepted his surrender and supported him as king. He forgave Ullusunu's rebellion and gained his loyalty.

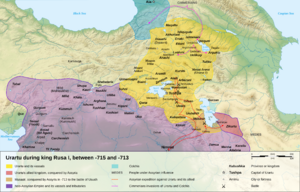

The War with Urartu

Urartu remained Sargon's main rival in the north. In 715 BC, Urartu was greatly weakened by a failed trip against the Cimmerians. The Cimmerians were a nomadic people from the central Caucasus. They defeated the Urartian army and raided Urartian lands. Ullusunu of Mannea had switched his loyalty to Assyria. Rusa took some of Ullusunu's fortresses and replaced him with Daiukku as the new king. Months later, Sargon invaded Mannea. He recaptured Ullusunu's fortresses and put him back on the throne. Rusa tried to push Sargon back, but his army was defeated. Sargon also received tribute from Ianzu, king of Nairi, another former Urartian ally.

To prepare for a campaign against Rusa, Sargon defeated some smaller rebels in Media. In Anatolia, Urik of Quwê switched his loyalty from Sargon to Midas of Phrygia. He began sending messages to Rusa. To stop a northern alliance from forming, Sargon attacked Quwê. He defeated Urik and recaptured some cities that Midas had taken. Quwê was no longer a vassal kingdom and was taken over by Assyria.

Rusa suspected an Assyrian invasion. He kept most of his army near Lake Urmia, close to the Assyrian border. This area was already fortified against Assyrian attacks. The shortest way from Assyria to the heart of Urartu was through a mountain pass. One of the most important places in Urartu, the holy city Musasir, was just west of this pass. It was protected by strong defenses. Rusa ordered the building of a new fortress called the Gerdesorah on a hill. The Gerdesorah was still being built when the Assyrians invaded.

Sargon left the Assyrian capital of Nimrud in July 714 BC. He did not take the shortest route through the mountain pass. Instead, Sargon marched his army through valleys for three days. He stopped near Mount Kullar. Sargon chose a longer route through Kermanshah. He probably knew the Urartians expected him to attack through the pass. The longer route meant crossing mountains and more distance. The campaign had to finish before October, when snow would block the mountain passes. This meant a full conquest would not be possible.

Sargon reached Gilzanu, near Lake Urmia, and set up camp. The Urartian forces regrouped and built new defenses west and south of Lake Urmia. Sargon's army had received supplies from his allies in Media. But his troops were tired and almost ready to rebel. When Rusa arrived, the Assyrian army refused to fight. Sargon gathered his bodyguards and led them in a charge against the nearest part of the Urartian forces. Sargon's army followed him. They defeated the Urartians and chased them far west of Lake Urmia. Rusa left his forces and fled into the mountains.

On their way home, the Assyrians destroyed the Gerdesorah. They captured and looted Musasir after its local ruler, King Urzana, refused to welcome Sargon. A huge amount of treasure was taken back to Assyria. Urzana was forgiven and allowed to continue ruling Musasir as an Assyrian ally. Urartu remained strong, and Rusa took back Musasir. But the 714 BC campaign ended direct fights between Urartu and Assyria for the rest of Sargon's rule. Sargon considered this campaign one of the most important events of his reign. It was described in great detail in his writings. Many carvings in his palace showed scenes of the looting of Musasir.

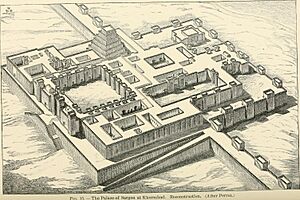

Building Dur-Sharrukin: Sargon's New Capital

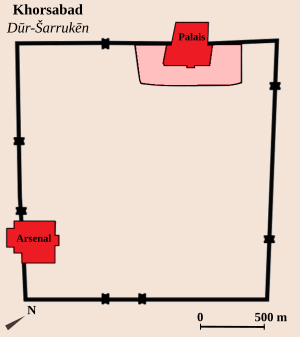

The building of Dur-Sharrukin ("fortress of Sargon") began in 717 BC. This new city was built between the Husur river and Mount Musri. It was near the village of Magganabba, about 16 kilometers northeast of Nineveh. The city could use water from Mount Musri. But otherwise, the location did not have clear practical or political benefits. In one of his writings, Sargon said he liked the foothills of Mount Musri. He wrote, "following the prompting of my heart, I built a city at the foot of Mount Musri, in the plain of Nineveh, and named it Dur-Sharrukin."

No buildings had ever been constructed at this spot before. So, Sargon did not have to worry about existing structures. He designed the new city as an "ideal city." Its design was based on mathematical harmony. There were many number and shape connections between different parts of the city. Dur-Sharrukin's city walls formed a nearly perfect square.

Many records about the city's construction still exist. These include writings carved on the buildings' walls and carvings showing the building process. There are also over a hundred letters and other documents describing the work. The main person in charge was Tab-shar-Ashur, Sargon's chief treasurer. But at least 26 governors from across the empire also helped with the building. Sargon made the project a team effort for the whole empire.

Sargon took a very active interest in the progress. He often got involved in almost every part of the work. This included commenting on building details, overseeing material transport, and hiring workers. Sargon's frequent input and efforts to encourage more work probably helped the city be finished so quickly and efficiently. Sargon's encouragement was sometimes gentle, especially when workers complained. But at other times, he used threats.

Dur-Sharrukin showed how Sargon saw himself and how he wanted the empire to see him. At about three square kilometers, the city was one of the largest in ancient times. The city's palace, which Sargon called a "palace without rival," was built on a huge artificial platform on the north side of the city. It had its own fortified wall. At 100,000 square meters, it was the largest Assyrian palace ever built. It was richly decorated with carvings, statues, colorful bricks, and stone lamassus (human-headed bulls).

Other important buildings in the city included temples, a building in the southwest called the arsenal, and a large park. The park had exotic plants from all over the empire. The city's surrounding wall was 20 meters high and 14 meters thick. It had over two hundred bastions (strong parts of the wall) every 15 meters. The inner wall was named Ashur, and the outer wall was named Ninurta. The city's seven gates were named after gods: Shamash, Adad, Enlil, Anu, Ishtar, Ea, and Belet-ili.

More Conflicts and Battles

After the campaign against Rusa, Sargon worked to keep his northern allies loyal. He also tried to limit the influence of Elam. Elam itself was not a threat to Assyria. But Sargon knew he could not take back Babylonia without breaking Marduk-apla-iddina's alliance with the Elamites. In 713 BC, Sargon campaigned in the Zagros Mountains again. He defeated a revolt in the land of Karalla, met with Ullusunu, and received some tribute. In the same year, Sargon sent his turtanu (commander-in-chief) to help Talta of Ellipi. Ellipi was an Assyrian ally beyond the Zagros Mountains. Sargon likely thought it was important to keep good relations with Ellipi. It was a key buffer state between Assyria and Elam. Talta was threatened by a revolt, but with Assyrian help, he kept his throne.

Rusa still wanted to expand Urartu's influence into southern Anatolia, despite Sargon's 714 BC victory. In 713 BC, Sargon campaigned against Tabal in southern Anatolia again. He wanted to secure the kingdom's natural resources (mainly silver and wood, needed for Dur-Sharrukin's construction). He also wanted to stop Urartu from gaining control and contacting Phrygia. Sargon used a "divide and rule" method in Tabal. He divided territory among different Tabalian rulers. This stopped any one of them from becoming too strong. Sargon also encouraged the strongest Tabalian state, Bit-Purutash, to have loose control over the other Tabalian rulers. The king of Bit-Purutash, Ambaris, was given Sargon's daughter Ahat-Abisha in marriage. He also received more territory. This plan did not work. Ambaris started plotting with the other rulers of Tabal, and with Rusa and Midas. Sargon removed Ambaris from power, sent him to Assyria, and took over Tabal.

The Philistine city of Ashdod rebelled under its king Azuri in 713 BC. Sargon or one of his generals quickly crushed the rebellion. Azuri was replaced by Ahi-Miti as king. In 712 BC, the allied king Tarhunazi of Kammanu in northern Syria rebelled against Assyria. He sought to ally with Midas. Tarhunazi had been placed on his throne during Sargon's 720 BC campaign in the Levant. Sargon's commander-in-chief dealt with this revolt. Tarhunazi was defeated, and his lands were taken over. His capital, Melid, was given to Mutallu of Kummuh. Mutallu was a trusted ally. The kings of Kummuh had long had good relations with the Assyrian court. After the Assyrian army defeated a revolt by the kingdom of Gurgum in 711 BC and took it over, Sargon's control of southern Anatolia became quite stable.

Soon after Sargon's victory, Ashdod rebelled again. The locals removed Ahi-Miti and made a noble named Yamani king instead. In 712 BC, Yamani tried to form an alliance with Judah and Egypt. But the Egyptians refused Yamani's offer, keeping good relations with Sargon. After the Assyrians defeated Yamani in 711 BC and Ashdod was destroyed, Yamani escaped to Egypt. He was later sent back to Assyria by Pharaoh Shebitku in 707 BC.

Taking Back Babylonia

In 710 BC, Sargon decided to take back Babylonia. To justify this, Sargon announced that the Babylonian god Marduk had told him to free the south from the evil Marduk-apla-iddina. Even though Babylonia and Elam were still friendly, their military alliance had broken apart. Sargon used diplomacy to convince cities and tribes in Babylonia to betray Marduk-apla-iddina. Through secret talks, several tribes and cities in northern Babylonia agreed to support Sargon. These included the city of Sippar and the tribes Bit-Dakkuri and Bit-Amukkani.

Sargon invaded Babylonia by marching along the eastern bank of the Tigris river. He reached the city of Dur-Athara, which Marduk-apla-iddina had fortified. But it was quickly defeated and renamed Dur-Nabu. Sargon created a new province around the city, called Gambulu. Dur-Athara might have been taken specifically to stop the Elamites from sending much help to Marduk-apla-iddina. Sargon stayed at Dur-Athara for some time. He sent his soldiers on trips to the east and south to convince cities and tribes to submit to his rule. Sargon's forces defeated a group of Aramean and Elamite soldiers near a river called the Uknu.

Once Sargon crossed the Tigris and a branch of the Euphrates and arrived at the city Dur-Ladinni, near Babylon, Marduk-apla-iddina became scared. He may have had little support from the people and priests of Babylon. Or he might have lost most of his army at Dur-Athara. Marduk-apla-iddina fled to Elam. There, he unsuccessfully asked King Shutruk-Nahhunte II for help.

After Marduk-apla-iddina left, Sargon faced little resistance on his march south. The people of Babylon happily opened their gates, and Sargon entered triumphantly. Historians think Sargon might have made a deal with the city's priests. They might have preferred Assyrian rule over a Chaldean king. After some ceremonies in the city, Sargon moved his army to Kish to continue the war and stop any remaining resistance. Marduk-apla-iddina returned to Mesopotamia. He settled in his home city of Dur-Yakin and continued to resist.

Dur-Yakin was fortified. A large ditch was dug around its walls. The surrounding countryside was flooded by a canal dug from the Euphrates. Protected by the flooded land, Marduk-apla-iddina set up his camp outside the city walls. His forces were defeated by Sargon's army, which crossed the flooded land without problems. Marduk-apla-iddina fled into the city as the Assyrians collected treasures from his fallen soldiers. Sargon besieged Dur-Yakin but could not take the city. As the siege continued, talks began. In 709 BC, it was agreed that the city would surrender and tear down its outer walls. In return, Sargon would spare Marduk-apla-iddina's life. Marduk-apla-iddina, his family, and supporters were allowed to go to Elam to live in exile.

Sargon's Final Years

After taking Babylon in 710 BC, Sargon was declared king of Babylon by the city's people. He spent the next three years in Babylon, living in Marduk-apla-iddina's palace. During these years, Sargon's son Sennacherib managed affairs in Assyria. Sargon took part in the yearly Babylonian New Year festival. He received gifts from rulers as far away as Bahrain and Cyprus. Sargon also got involved in local matters in Babylonia. He dug a new canal from Borsippa to Babylon. He defeated a group called the Hamaranaeans who had been robbing caravans near Sippar. In Sargon's writings from this time, he used some traditional Babylonian titles. He often mentioned gods popular in Babylonia rather than those popular in Assyria. Some Assyrians, even royal family members, disagreed with Sargon's pro-Babylonian attitude.

While Sargon was away, his officials and generals handled events in the rest of the empire. Midas of Phrygia remained a threat to Assyrian interests. To keep communication and trade open to Assyrian allies in Anatolia, the Assyrians watched him carefully. In 709 BC, the Assyrian governor of Quwê, Ashur-sharru-usur, decided to end the Phrygian threat. His raids into Phrygia and the capture of a mountain fortress scared Midas. Midas then willingly became Sargon's ally.

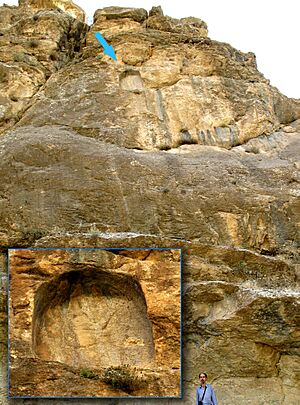

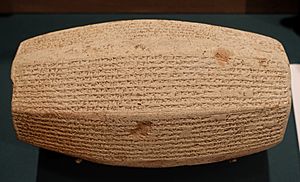

In 709 BC, Assyria sent an expedition to Cyprus. This was the first time the Assyrians learned much about the island. Sargon did not personally join the campaign. The Assyrians relied on their allies in the Levant for transport. Because Cyprus was far away, actually controlling the island would have been hard. But the campaign led to several Cypriot rulers paying tribute to Sargon. After the expedition left, the Cypriots, likely with help from an Assyrian stonemason, created the Sargon Stele. This stone monument showed the boundary of the Assyrian king's power. It marked Cyprus as part of the Assyrians' "known world." Since it had the king's image and words, it represented Sargon and acted as if he were present.

In 709 BC, one of Sargon's officers besieged the Phoenician city of Tyre. Its leader had refused to ally with Assyria. This turned out to be one of Sargon's few military mistakes. The city resisted the Assyrians for several years until Sargon's death. After that, the Assyrian army left. In 708 BC, Mutallu of Kummuh stopped paying tribute to Assyria for unknown reasons. He allied with the new Urartian king Argishti II. Sargon sent one of his officers to capture Kummuh. The Assyrians heavily looted Kummuh and took over its lands. Mutallu survived, probably escaping to Urartu.

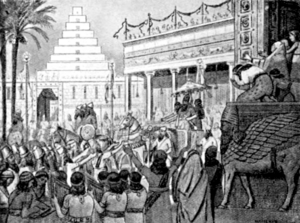

Dur-Sharrukin was finished in 707 BC after ten years of building. Sargon returned to Assyria to prepare for the city's opening. A year later, he moved the royal court to Dur-Sharrukin. The opening began with Sargon "inviting the gods" to Dur-Sharrukin. He placed statues of various gods in the city's temples. Sargon invited "princes of (all) countries, the governors of my land, scribes and superintendents, nobles, officials and elders of Assyria" to a great feast. The common people who helped build the city were also invited to the celebration. They dined in the same hall as the king. Soon after its opening, the new capital was already very populated.

Sargon's Last Campaign and Death

Few records describe Sargon's last campaign and death. Based on historical lists and chronicles, Sargon likely went to fight against Tabal in early summer 705 BC. Tabal had rebelled against him. This campaign was the last of several attempts to bring Tabal under Assyrian control. It is not clear why Sargon decided to lead this trip himself. He had many officials and generals who could lead campaigns. Tabal was not a real threat to the Assyrian Empire. Some historians believe Sargon saw the trip as an interesting break from the quiet court life in Dur-Sharrukin.

Sargon's final campaign ended badly. Somewhere in Anatolia, Gurdî of Kulumma, a little-known figure, attacked the Assyrian camp. Gurdî is thought to have been a local ruler in Anatolia or a Cimmerian tribal leader. The Cimmerians were allied with the rebels in Tabal at this time. In the battle, Sargon was killed. The Assyrian soldiers fleeing the attack could not get the king's body back. Sargon died just over a year after Dur-Sharrukin was opened.

Sargon's Family and Children

Sargon had a younger brother named Sin-ahu-usur. By 714 BC, he was the commander of Sargon's royal cavalry guard. After Dur-Sharrukin was opened in 706 BC, he was given his own home in the new capital. He seems to have held the important position of grand vizier.

We know of two wives of Sargon: Ra'ima and Atalia. Atalia was Sargon's queen. Her tomb was found in Nimrud in 1989. Historians generally think that Assyrian kings could have many wives. But only one woman at a time could be recognized as queen. Sennacherib was once thought to be Atalia's son. But we now know he was the son of Ra'ima. A stone carving from Assur, translated in 2014, clearly says Ra'ima was his mother. There is no proof that Ra'ima was ever Sargon's queen. Atalia is believed to have lived longer than Sargon. Her remains show she was about 30–35 years old when she died. Ra'ima must have been much older than Atalia, as she gave birth to Sennacherib around 745 BC. It is possible that Ra'ima also lived longer than Sargon. A writing by Sennacherib in 692 BC mentions her, though it might have been written after her death.

Sargon had at least two sons before Sennacherib was born. However, they died before Sennacherib's birth. This is shown by Sennacherib's name, Sîn-ahhī-erība, which means "[the god] Sîn has replaced the brothers." Like Sennacherib, the older sons were likely Ra'ima's children. Sennacherib, who became king after Sargon (705–681 BC), was an adult when Sargon became king. He was named crown prince early in Sargon's reign. He helped his father run the empire, including collecting and summarizing reports from the Assyrian spy network. Sargon had at least two children younger than Sennacherib, but their names are unknown. Their existence is mentioned in a letter from Sargon's time. It talks about "Sennacherib, the crown prince ... [and all] the princes/children of the king (who are) [in] Assyria." Sargon's only known daughter was Ahat-Abisha. She married Ambaris of Tabal. When Sargon removed Ambaris from power in 713 BC, Ahat-Abisha likely returned to Assyria.

Sargon's Character and Rule

A Warrior-King and Strategist

Sargon II was a warrior-king and conqueror. He personally led his armies and dreamed of conquering the world, like Sargon of Akkad. Sargon used traditional Mesopotamian titles related to world domination. These included "king of the universe" and "king of the four corners of the world." He also used titles like "great king" and "mighty king." Assyrian kings' titles often followed a pattern. But they usually added special descriptions to show their unique qualities. Sargon's descriptions made him seem like an unbeatable warlord. For example, "mighty hero, clothed with terror, who sends forth his weapon to bring low the foe, brave warrior, since the day of whose (accession) to rulership, there has been no prince equal to him, who has been without conqueror or rival." Sargon wanted to be seen as an ever-present and eager fighter. He probably did not fight on the front lines in all campaigns. This would have been too risky for the empire. But it is clear he was more interested in war than the kings before and after him. He did eventually die in battle.

Sargon was a very successful military strategist. He used a large spy network, which was helpful for government and military activities. He also used well-trained scouts to gather information during campaigns. Even though the Assyrian Empire was much stronger than any of its enemies, these enemies surrounded the empire. Because only one target could be attacked at a time, enemies had to be chosen wisely to avoid disaster. Sargon outsmarted his enemies many times. For example, he took an unexpected route in the war with Urartu. Sargon's ability to quickly react and adapt to problems set him apart from earlier kings.

Sargon also made the Assyrian army stronger. He was the first Assyrian king to understand the power of cavalry (soldiers on horseback). He made many improvements. These included choosing certain horse breeds, developing new ways of harnessing horses, and hiring mercenary cavalry. Based on his letters, Sargon seemed to ensure discipline through fear rather than inspiration. When gathering troops, he sometimes threatened them with the same punishments used against Assyria's worst enemies if they disobeyed him.

Unlike the many records of such punishments against Assyrian enemies, there is no proof that Sargon's threats were carried out. It is unlikely they ever were. Because soldiers often took part in punishing enemies, the threats themselves were probably enough. Despite this approach, Sargon was not unpopular with the military. There are no records of army rebellions against him or of officers plotting against him. It is also likely that the main reason Assyrians served in the army was not the king's threats. Instead, it was the frequent spoils of war they could take after victories.

A King Seeking Lasting Fame

Almost all Assyrian kings wanted to do better than the kings before them. They wanted to be remembered as glorious rulers. Sargon wanted to surpass all previous kings, even Sargon of Akkad. He created his own cult of personality. For example, he had stone slabs made with his image as a powerful king. He placed these across the empire, often in very visible places. In his palace in Dur-Sharrukin, Sargon decorated the walls with carvings showing himself and his achievements. He hoped that future generations would see him as one of the greatest kings.

Sargon's desire for fame is also seen in Dur-Sharrukin. The city was likely built mainly to make a statement, since its location had no clear benefits. Perhaps inspired by Sargon of Akkad, who was credited with founding the city of Akkad, Sargon II built Dur-Sharrukin for his own glory. He intended the city and his other building projects to preserve his memory for generations. The writings in Dur-Sharrukin show Sargon's wish to start a golden age and a new world order. They also warned against anyone who would destroy Sargon's works. They encouraged future kings to honor his memory.

Besides Sargon of Akkad, another figure Sargon II admired was the ancient Sumerian ruler Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh was mainly known in Sargon's time through the Epic of Gilgamesh. In several surviving texts, Sargon II's achievements were compared to the legend. In Sargon's writings, the campaign against Urartu includes parts where it seems Sargon is fighting not only the Urartians but also the land itself. A section describes mountains rising like swords and spears to stop Sargon's advance. This would have reminded Assyrian readers of a similar part in the Epic of Gilgamesh. It suggested that Sargon faced dangers equal to those of the ancient hero. A giant carving at Dur-Sharrukin shows a strong man holding a lion to his chest. Although there is no writing to prove it, scholars generally believe it shows Gilgamesh. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh does not become truly immortal. But he achieves a kind of immortality by building an impressive wall around Uruk. This building work would last longer than him and keep his memory alive.

A Guardian of Justice

Sargon called himself a "guardian of justice." He believed he was chosen by the gods to "maintain justice and right." He also aimed to "give guidance to those who are not strong" and "not to injure the weak." Sargon worked to protect and secure the people under his rule.

Under Tiglath-Pileser, Assyria began to include and integrate conquered foreign peoples. Sargon continued and expanded this policy. He put foreigners on the same level as the original Assyrian population. Sargon's accounts of conquests clearly state that he placed the same taxes on people in new territories as he did on people in the Assyrian heartland. Sargon also encouraged people to blend cultures and learn Assyrian ways of life, rather than forcing them.

The power and influence of women at the royal court increased during Sargon's reign. He created new military units that served the queen. These units grew in size and variety under Sargon's successors. These units were part of the empire's military strength and took part in campaigns. Sargon's reasons are not known. But perhaps he wanted to reduce the power of strong officials. He might have done this by giving authority to trusted relatives, including women. The office of turtanu (commander-in-chief) was split into two. One was assigned to the queen's forces.

In Assyrian royal beliefs, the Assyrian king was the god Ashur's chosen representative on Earth. The king was seen as having a moral duty to expand Assyria. Lands outside Assyria were thought to be uncivilized and a threat to the order within the Assyrian Empire. So, expansion was seen as a moral duty to bring civilization out of chaos. Unlike almost all other Assyrian kings, Sargon did not only rule through aggression. He kept good relations with several foreign ruling classes and kings. He rewarded loyal allies. And he sometimes spared and forgave enemies who surrendered.

Sargon saw himself as very intelligent, more so than any king before him. He probably received the usual education of the Assyrian upper class. He learned both Akkadian and Sumerian, as well as some arithmetic. Sargon might also have been educated in art or literature. He built a library in his palace and decorated the palace walls with artwork. Sargon strongly promoted writing and scholarly culture. Court scholars became more important during Sargon's reign than before or after. Over a thousand clay tablets with letters are known from Sargon's time. This is more than from the reigns of his three successors combined.

Sargon's Legacy

Sargon Forgotten by History

Sargon's reputation in ancient Assyria was badly damaged by how he died. Especially, the failure to get his body back was a big shock for Assyria. The shock and religious meaning of his death affected the reigns of his successors for decades. Ancient Assyrians believed that unburied dead people became ghosts. These ghosts could come back and haunt the living. Sargon was thought to be doomed to a terrible afterlife. His ghost would wander the Earth, always restless and hungry.

Soon after news of Sargon's death reached Assyria, an important advisor and scribe copied a part of the Epic of Gilgamesh. This part describes a situation eerily similar to Sargon's death. It details the miserable consequences, which must have deeply troubled the scribe. In the Levant, Sargon's pride was mocked. It is believed that a foreign ruler criticized in the Biblical Book of Isaiah is based on Sargon.

Sennacherib was horrified by his father's death. Historians believe Sennacherib was so affected that he might have suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder. Sennacherib could not accept what had happened. Sargon's dishonorable death in battle and lack of burial was seen as a sign. It meant he must have committed some serious sin that made the gods completely abandon him. Sennacherib concluded that Sargon had perhaps offended Babylon's gods by taking control of the city.

Sennacherib did everything he could to distance himself from Sargon. He never wrote or built anything to honor Sargon's memory. One of his first building projects was restoring a temple dedicated to Nergal, the god of the underworld. This was perhaps meant to calm a god possibly involved with Sargon's fate. Sennacherib also moved the capital to Nineveh. This was despite Dur-Sharrukin being brand new and built for the royal court. Given that Sargon based parts of his rule on Gilgamesh, it is possible that Sennacherib abandoned Dur-Sharrukin because of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The angry and hungry spirit of a mighty king might have made Sennacherib fear holding court there. Sennacherib spent a lot of time and effort to remove Sargon's images and works from the empire. Images Sargon had created at the temple in Assur were covered up. Sargon's queen Atalia was buried quickly when she died. This was done without following traditional burial practices, and in the same coffin as another woman. Despite this, Sennacherib tried to avenge his father. He sent an expedition to Tabal in 704 BC to kill Gurdî and perhaps get Sargon's body back. We do not know if it was successful.

After Sennacherib's reign, Sargon was sometimes mentioned as an ancestor of later kings. Assyria fell in the late 7th century BC. While the local people of northern Mesopotamia never forgot ancient Assyria, knowledge of Assyria in Western Europe came from classical writers and the Bible. Because of Sennacherib's efforts, Sargon was poorly remembered when these works were written. Sargon was not well-known in the study of Assyria until Dur-Sharrukin was rediscovered in the 1800s. His name appears only once in the Bible (Isaiah 20.1). He is not mentioned in classical sources. Historians were puzzled by his name in the Bible. They often thought it was a second name for one of the better-known kings, like Shalmaneser, Sennacherib, or Esarhaddon.

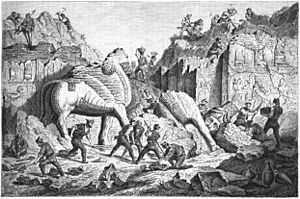

Sargon Rediscovered

European explorers and archaeologists began digging in northern Mesopotamia in the early 1800s. Around this time, some scholars started to think Sargon was a distinct king between Shalmaneser and Sennacherib. Dur-Sharrukin was found by chance. Paul-Émile Botta was digging at Nineveh when he heard about it from locals in 1843. Botta and his assistant Victor Place excavated almost the entire palace. They also dug up parts of the surrounding town. In 1847, the first exhibition of Assyrian sculptures was held in the Louvre. It featured finds from Sargon's palace. Botta's report on his findings, published in 1849, created great interest. Much of what was dug up at Dur-Sharrukin was left in place. But carvings and other artifacts have been shown around the world. These include the Louvre, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, and the Iraq Museum.

In 1845, Isidore Löwenstern was the first to suggest that Sargon built Dur-Sharrukin. However, his idea was based on incorrect readings of ancient writings. After ancient cuneiform writing was understood, archaeologist Adrien Prévost de Longpérier confirmed the king's name was Sargon in 1847. Discussions and debates continued for several years. Sargon was not fully accepted by historians as a distinct king until the 1860s.

Because of the many records left from his time, Sargon is better known than many kings before and after him. He is also better known than the ancient Sargon of Akkad. Modern historians consider Sargon to be one of the most important Assyrian kings. This is because he greatly expanded Assyrian territory and made important changes to the government and military. Sargon left behind a stable and strong empire. However, it proved difficult for his successors to control. Sennacherib had to face several revolts against his rule. Some of these were because of how Sargon died. But all were eventually defeated. In 2017, historian Josette Elayi called Sargon "the real founder of the empire." She said he "succeeded in everything in his life, but completely failed in his death." Since the early 1900s, Sargon has also been a common name among modern Assyrian people.

Titles

See also

In Spanish: Sargón II para niños

In Spanish: Sargón II para niños

- List of Assyrian kings

- Military history of the Neo-Assyrian Empire

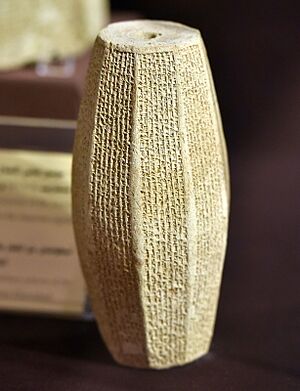

- Sargon II's Prisms

- Annals of Sargon II