Samaria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Samaria |

|

|---|---|

Hills near the ruins of Samaria

|

|

| Coordinates | 32°16′30″N 35°11′24″E / 32.275°N 35.190°E |

| Part of | West Bank, Palestine |

| Highest point – elevation |

Tall Asur (Ba'al Hazor) 1,016 m (3,333 ft) |

| Geology | Region |

| Designation | السامرة, שֹׁומְרוֹן |

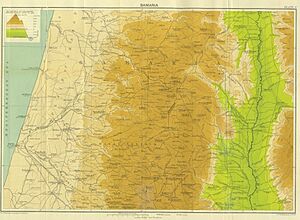

Samaria is a historic region in the central part of Israel. Its name comes from the Hebrew word "Shomron." People in Palestine also call it Samirah or Mount Nablus. To the south, it borders Judea, and to the north, it borders Galilee.

An ancient historian named Josephus said Samaria stretched from the Mediterranean Sea in the west to the Jordan River in the east. This area mostly matches the lands given to the tribe of Ephraim and half of the Manasseh tribe in the Hebrew Bible. It includes most of the land that was once the ancient Kingdom of Israel, which was north of the Kingdom of Judah. The border between Samaria and Judea is around the city of Ramallah.

The name "Samaria" comes from the ancient city of Samaria. This city used to be the capital of the northern Kingdom of Israel. The region likely started being called Samaria after the city became the capital. It was first officially recorded after the Neo-Assyrian Empire took over the land and made it a province called Samerina.

In 1947, the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine used "Samaria" to describe the northern middle part of the land. After the Six-Day War in 1967, Israeli officials started using the term "Samaria" for the area north of Jerusalem District in the West Bank. In 1988, Jordan gave up its claim to this area to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In 1994, Israel transferred control of some areas (called 'A' and 'B') to the Palestinian Authority. The Palestinian Authority and many other countries don't use the term "Samaria" today. They usually refer to this land as part of the West Bank.

Contents

What's in a Name?

According to the Hebrew Bible, the Hebrew name "Shomron" comes from a person or family named Shemer. King Omri (who ruled around 880-870 BCE) bought a hill from Shemer and built his new capital city, Shomron, there.

The mountain might have been called Shomeron even before Omri bought it. This could mean the name comes from a Semitic word meaning "guard." So, its first meaning might have been "watch mountain." In older writings, Samaria was called "Bet Ḥumri" ("the house of Omri"). But later, during the time of Tiglath-Pileser III (who ruled 745-727 BCE), it was called Samirin, which is its Aramaic name, Shamerayin.

Where is Samaria?

The area known as the hills of Samaria is surrounded by other regions. To the north is the Jezreel Valley. To the east is the Jordan Rift Valley. The Carmel Ridge is to the northwest, and the Sharon plain is to the west. To the south are the Jerusalem mountains.

The Samarian hills are not very tall, usually less than 800 meters high. The weather in Samaria is nicer than in the areas further south. There isn't a clear border between the mountains of southern Samaria and northern Judea.

A Look Back in Time

Over many centuries, different groups have controlled the Samaria region. These include the Canaanites, Israelites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Seleucids, Hasmoneans, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Crusaders, and Ottoman Turks.

Israelite Tribes and Kingdoms

According to the Hebrew Bible, the Israelites took the Samaria region from the Canaanites. They gave this land to the Tribe of Joseph. The southern part of Samaria was then called Mount Ephraim. After King Solomon died around 931 BC, the northern tribes, including Ephraim and Menashe, broke away. They formed their own country, the Kingdom of Israel.

At first, their capital was Tirzah. Then, King Omri (around 884 BC) built the city of Samaria and made it his capital. Samaria was the capital of the northern Kingdom of Israel until the Assyrians conquered it in the 720s BC. Hebrew prophets criticized Samaria for its "ivory houses" and fancy palaces filled with riches from other religions.

Archaeological findings show that Samaria grew a lot in the Iron Age II (from about 950 BC). Experts believe there were 400 sites, up from 300 in the earlier Iron Age I (around 1200 BC). People lived in small villages, farms, forts, and cities like Shechem, Samaria, and Tirzah. One expert, Zertal, estimated that about 52,000 people lived in the Manasseh Hill area of northern Samaria before the Assyrians moved them away. Botanists say that most of Samaria's forests were cut down during the Iron Age II to make way for farms. Since then, only a few oak forests have grown back.

Assyrian Period

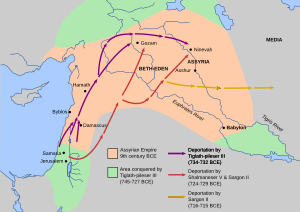

In the 720s BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire conquered Samaria. This included a three-year siege of the capital city of Samaria. The Assyrians then made the land into a province called Samerina. The siege likely happened around 725 or 724 BC and ended in 722 BC. The first time the province of Samerina is mentioned is during the rule of Sargon II, who took over after Shalmaneser V. This is also the first time a name from "Samaria," the capital city, was used for the whole region, though people probably did this earlier.

After the Assyrian conquest, Sargon II wrote that he moved 27,280 people to different parts of his empire. Many went to Guzana in the Assyrian heartland, and others went to cities in the land of the Medes (modern-day Iran). Moving people was a common way the Assyrians dealt with defeated enemies. The people who were moved were generally treated well and brought their families and belongings with them. At the same time, people from other parts of the empire were moved into the less populated Samerina. This event is also known as the Assyrian captivity in Jewish history and is part of the story of the Ten Lost Tribes.

Babylonian and Persian Periods

Many experts say that archaeological digs at Mount Gerizim show a Samaritan temple was built there in the first half of the 5th century BCE. It's not clear when the Samaritans and Jews fully separated, but by the early 4th century BCE, they seemed to have different practices. Much of the negative writing about Samaritans in the Hebrew Bible and other old texts comes from this time.

Hellenistic Period

During the Hellenistic period, Samaria was mostly split into two groups. One group, based in the town of Samaria, followed Greek ways. The other group, in Shechem and nearby rural areas, was very religious and led by the High Priest.

Samaria was mostly self-governing, but it was officially part of the Seleucid Empire. However, the region slowly became weaker as the Maccabean movement and Hasmonean Judea grew stronger. For example, three districts of Samaria—Ephraim, Lod, and Ramathaim—were given to Judea in 145 BCE. This showed Samaria's decline. Around 110 BCE, Hellenistic Samaria was completely weakened when the Jewish Hasmonean ruler John Hyrcanus destroyed the cities of Samaria and Shechem, as well as the city and temple on Mount Gerizim. Today, only a few stone pieces of the Samaritan temple remain.

Roman Period

In 6 CE, Samaria became part of the Roman province of Iudaea, after the death of King Herod.

Southern Samaria had the most settlements during the early Roman period (63 BCE–70 CE). This was partly because the Hasmonean dynasty had encouraged people to settle there. The effects of the Jewish–Roman wars can be seen in Jewish areas of southern Samaria. Many sites were destroyed and left empty for a long time. After the First Jewish–Roman War, the Jewish population in the area dropped by about 50%. After the Bar Kokhba revolt, the Jewish population was completely gone in many places. According to Klein, the Roman authorities replaced the Jews with people from nearby Roman provinces like Syria, Phoenicia, and Arabia. A new wave of settlement growth in southern Samaria, likely by non-Jews, can be seen in the late Roman and Byzantine times.

Byzantine Period

After the bloody Samaritan revolts (mostly in 525 CE and 555 CE) against the Byzantine Empire, many Samaritans died, were moved, or changed to Christianity. This caused the Samaritan population to drop a lot. In the central parts of Samaria, nomads moved into the empty areas left by Samaritans and slowly settled down.

The Byzantine period is seen as the time when Samaria had the most settlements. Based on old writings and archaeological finds, experts believe that Samaria's population during the Byzantine period included Samaritans, Christians, and a small number of Jews. The Samaritan population mostly lived in the Nablus valleys and north to Jenin. They did not settle south of the Nablus-Qalqiliya line. Christianity slowly spread in Samaria, even after the Samaritan revolts. Except for Neapolis, Sebastia, and a few monasteries in central and northern Samaria, most people in the rural areas remained non-Christian. In southwestern Samaria, many churches and monasteries were found. Some were built on top of old forts from the late Roman period. Magen suggested that many of these were used by Christian pilgrims and filled empty spaces in the region where the Jewish population had been wiped out during the Jewish–Roman wars.

Early Muslim, Crusader, Mamluk, and Ottoman Periods

After the Muslim conquest of the Levant, and throughout the early Islamic period, Samaria became more Muslim. This happened as many remaining Samaritans converted, and Muslims moved into the area. Evidence suggests that many Samaritans converted during the rule of the Abbasids and Tulunids. This was due to droughts, earthquakes, religious attacks, high taxes, and disorder. By the middle of the Middle Ages, the Jewish writer Benjamin of Tudela estimated that only about 1,900 Samaritans were left in Palestine and Syria.

Ottoman Period

During the Ottoman period, the northern part of Samaria was part of the Turabay Emirate (1517–1683). This emirate also included the Jezreel Valley, Haifa, Jenin, Beit She'an Valley, northern Jabal Nablus, Bilad al-Ruha/Ramot Menashe, and the northern Sharon plain. The areas south of Jenin, including Nablus itself and its surrounding land up to the Yarkon River, formed a separate district called the District of Nablus.

British Mandate

During the Great War (World War I), the British army took control of Palestine from the Ottoman Empire. After the war, the United Kingdom was given the job of managing Palestine as a League of Nations mandated territory. Samaria was the name of one of the administrative districts of Palestine during part of this time. The 1947 UN partition plan suggested that the Arab state should have several parts, and the largest part was described as "the hill country of Samaria and Judea."

Jordanian Period

After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, most of the territory was taken by Jordan. It was then managed as part of the West Bank (the land west of the Jordan river).

Israeli Administration

The West Bank, which was held by Jordan, was captured and occupied by Israel after the 1967 Six-Day War. Jordan gave up its claims in the West Bank (except for some rights in Jerusalem) to the PLO in November 1988. This was later confirmed by the Israel–Jordan Treaty of Peace in 1994. In the 1994 Oslo accords, the Palestinian Authority was created. It was given responsibility for managing some areas of the West Bank (called Areas 'A' and 'B').

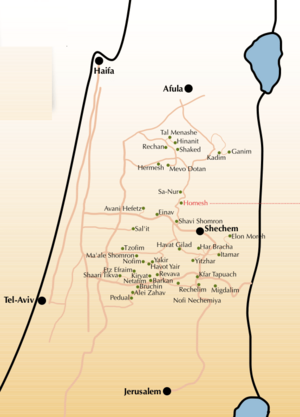

Samaria is one of the standard statistical districts used by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. This group also collects information on the rest of the West Bank and the Gaza District, covering things like population, jobs, and trade. However, the Palestinian Authority uses Nablus, Jenin, Tulkarm, Qalqilya, Salfit, Ramallah, and Tubas governorates as administrative centers for the same region.

The Shomron Regional Council is the local government that manages the smaller Israeli towns (called settlements) in the area. This council is part of a network of regional governments across Israel. Elections for the head of the council happen every five years, and all residents over 17 can vote. In August 2015, Yossi Dagan was elected as the head of the Shomron Regional Council.

Most of the international community considers Israeli settlements in the West Bank to be against international law. However, some, including the United States and Israeli governments, disagree. In September 2016, the Town Board of Hempstead, New York, led by Councilman Bruce Blakeman, partnered with the Shomron Regional Council, led by Yossi Dagan. This was part of a campaign against the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement.

Ancient Discoveries

Ancient City of Samaria/Sebaste

The ancient site of Samaria-Sebaste is on a hillside overlooking the village of Sebastia in the West Bank. Remains have been found from many different time periods, including the Canaanite, Israelite, Hellenistic, Roman (including Herodian), and Byzantine eras.

Archaeological finds from the Roman-era Sebaste, which was rebuilt and renamed by Herod the Great in 30 BC, include a street with columns, a temple-filled hilltop, and a lower city. It is believed that John the Baptist was buried in the lower city.

The Harvard excavation of Samaria started in 1908 and was led by Egyptologist George Andrew Reisner. They found writings in Hebrew, Aramaic, cuneiform, and Greek, as well as pottery, coins, sculptures, and other artifacts. A joint British-American-Hebrew University excavation continued from 1931–35. During this time, they figured out some of the dates of the findings. For example, the round towers on the hilltop were from the Hellenistic period, the street of columns was from the 3rd-4th century, and 70 inscribed pottery pieces were from the early 8th century.

Between 1908 and 1935, remains of fancy furniture made of wood and ivory were found in Samaria. These are the most important collection of ivory carvings from the early first millennium BC in the area. Even though some think they came from Phoenicia, some of the letters used as marks on them are in Hebrew.

By 1999, three sets of coins had been found that confirm Sinuballat was a governor of Samaria. Sinuballat is known as an enemy of Nehemiah from the Book of Nehemiah, where he is said to have sided with Tobiah the Ammonite and Geshem the Arabian. All three coins show a warship on the front, likely copied from older coins from Sidon. The back of the coins shows the Persian King facing a lion standing on its back legs.

Other Ancient Sites

- The Bull Site: An ancient worship site from the Iron Age I.

- Tel Dothan: Near Jenin, believed to be the biblical Dothan.

- Khirbet Kheibar: In Meithalun, an ancient mound inhabited from the Middle Bronze Age to Medieval times.

- Khirbet Kurkush: Site of an ancient Samaritan or Jewish settlement with a notable burial ground.

- Khirbet Samara: Site of a notable ancient Samaritan synagogue.

- Nablus area:

- Mount Gerizim: The most important religious place for Samaritanism, with an ancient Samaritan temple and Samaritan and Byzantine ruins.

- Mount Ebal site: Iron Age remains on Mount Ebal, seen by many experts as an early Israelite worship site.

- Tell Balata: Identified as the biblical city of Shechem.

- Khirbet Seilun/Tel Shiloh: Identified with Shiloh (biblical city).

- Tell el-Far'ah (North): Identified with biblical Tirzah, which was the third capital of the northern Kingdom of Israel.

Who are the Samaritans?

The Samaritans (in Hebrew, Shomronim) are a group of people named after and descended from ancient people who lived in Samaria. According to the Bible (2 Kings 17) and the historian Josephus, they are descendants of the ancient Semitic inhabitants of Samaria who remained after the Assyrian exile of the Israelites.

Religiously, Samaritans follow Samaritanism, which is a religion similar to Judaism. Based on the Samaritan Torah, Samaritans believe their way of worship is the true religion of the ancient Israelites, preserved by those who stayed behind after the Babylonian exile. Their temple was built on Mount Gerizim in the mid-5th century BCE. It was destroyed by the Hasmonean king John Hyrcanus of Judea in 110 BCE. However, their descendants still worship among its ruins today.

The disagreements between Samaritans and Jews are important for understanding Bible stories like the "Samaritan woman at the well" and the "Parable of the Good Samaritan" in the New Testament. However, modern Samaritans see themselves as equally connected to the Israelite heritage through the Torah, just like Jews, and they are not enemies with Jews today.

See Also

- Archevites

- Samaritan Revolts

- List of burial places of biblical figures

- Ahwat

- Judea and Samaria Area

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |