Herod the Great facts for kids

Herod I (born around c.73/75–4 BC), also known as Herod the Great, was a powerful king of Judea. He ruled from 37 BC to 4 BC. During his time, Judea was like a partner country to the mighty Roman Empire. Herod was known for being a very good leader and manager during his 33 years as king.

Contents

How Herod Became King

Herod was born around 73 or 75 BC. His father, Antipater the Idumaean, and his mother, Cyprus, were important people. His father and grandfather were both political leaders in Judea. They had strong connections with the Romans.

Herod became powerful mostly because his father had good ties with Julius Caesar. Caesar was a famous Roman general and leader. He trusted Antipater to manage things in Judea. In 47 BC, Antipater made his oldest son, Phasael, the governor of Jerusalem. He made Herod the governor of Galilee. As governor, Herod impressed the Romans by handling local rebellions. However, some of his actions were criticized by the Jewish council called the Great Sanhedrin.

Herod's Rule as King

Herod was friends with Octavian and Mark Antony. In 40 BC, the Roman Senate decided Herod should be the next king of Judea. Herod went to the Temple of Jupiter to thank the Roman gods. When the current king of Judea was killed in 37 BC, Herod officially became king.

In his early years as king, Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt, kept taking small parts of Herod's kingdom. This happened because she was allied with Mark Antony. But then, Octavian defeated Antony and Cleopatra in a big battle in 31 BC. Herod quickly made a new alliance with Octavian.

Herod became known for his strict taxes. However, he managed to keep peace in the region. He sent expensive gifts to Rome but did not have to pay regular taxes. By 30 BC, he had gotten back all the land Cleopatra and the Hasmoneans had taken. He also expanded his rule into northern Galilee. He helped resettle several areas. By giving generous gifts to Athens and supporting the Olympic Games, he made Judea more important in the Mediterranean world.

Herod's Major Projects

Herod saw himself as a perfect, sophisticated king. Even though some Bible writers called him a tyrant, he was very interested in Greco-Roman culture and philosophy. He sometimes neglected Jewish laws and state affairs. He needed the approval of the Pharisees (Jewish religious leaders) to rule. He tried many ways to get their support, but he never fully won them over.

For example, he built the city of Caesarea Maritima (between 22 and 10 BC). He built it to honor his patron, Caesar Augustus. But the pagan symbols in his cities upset the Jewish leaders. He also organized gladiator fights every five years, which further angered them.

In 20 BC, Herod started rebuilding the Second Temple, also known as Herod's Temple. He wanted the temple to be a magnificent monument to the Jewish faith. However, he used Greek architects. He also allowed moneylenders to work in the temple courtyard. This made many Jews very angry.

One of his biggest religious scandals was digging up King David's Tomb. He hoped to find a treasure there, as rumors suggested. He had spent a lot of money on his other projects. He thought secretly robbing the tomb would help him get money. But when he opened the tomb, there was no treasure.

Herod started many huge building projects. Around 19 BC, he began a massive expansion of the Temple Mount. He completely rebuilt and enlarged the Second Jewish Temple. He also made the platform it stood on much bigger. Herod also used the latest technology to build the harbor at Caesarea Maritima. This included special hydraulic cement for underwater construction.

Herod's passion for building changed Judea. But his reasons were not always selfless. He built strong fortresses like Masada, Herodium, and Machaerus. These were places where he and his family could hide if there was a rebellion. But these huge projects also aimed to gain support from the Jews. They also improved his reputation as a leader. Herod also built cities like Sebaste with pagan features. He wanted to appeal to the many non-Jewish people living in the country.

To pay for these projects, Herod used a taxation system that heavily burdened the people of Judea. However, these projects also created jobs and opportunities. In some cases, Herod helped his people during hard times. For example, he provided for them during a severe famine in 25 BC.

Herod's Death

Herod died in Jericho after a serious illness. This illness was later called "Herod's Evil."

Who Ruled After Herod

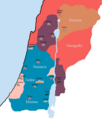

Augustus, the Roman emperor, respected Herod's will. Herod's will said his kingdom should be divided among three of his sons. Augustus recognized Herod's son Herod Archelaus as the ruler of Judea, Samaria, and Idumea from about 4 BC to 6 CE. Later, Augustus decided Archelaus was not a good ruler. He removed him from power. He then combined Samaria, Judea, and Idumea into a larger Roman province called Iudaea province. This province was ruled by a prefect until 41 CE.

Herod's other sons also ruled parts of the kingdom. Herod Antipas was the ruler of Galilee and Peraea from Herod's death until 39 CE. He was then removed from power and sent away. Philip became the ruler of lands north and east of the Jordan River. These included Iturea, Trachonitis, and Batanea. He ruled until his death in 34 CE.

Herod's Tomb

The location of Herod's tomb is written about by the historian Josephus. He wrote that Herod's body was carried "two hundred furlongs, to Herodium, where he had given order to be buried." Professor Ehud Netzer, an archaeologist from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, used Josephus's writings to search for the tomb. He focused his search near a large pool at Herodium.

An article in the New York Times described the area:

Lower Herodium has the remains of a large palace, a race track, and other buildings. One large building's purpose is still a mystery. Ehud Netzer, who dug at the site, thought it might be Herod's mausoleum (a grand tomb). Next to it is a pool, almost twice the size of modern Olympic-size pools.

On May 7, 2007, an Israeli team of archaeologists from Hebrew University, led by Netzer, announced they had found the tomb. The site was exactly where Josephus said it would be. It was on top of tunnels and water pools, on a flat desert spot. It was halfway up the hill to Herodium, about 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) south of Jerusalem. The tomb contained a broken sarcophagus (a stone coffin) but no body remains.

Not all experts agree with Netzer's discovery. In an article, archaeologist David Jacobson wrote that "these finds are not conclusive on their own and they also raise new questions." In October 2013, archaeologists Joseph Patrich and Benjamin Arubas also questioned if it was truly Herod's tomb. They said the tomb was too simple for Herod and had some strange features. Roi Porat, who took over the excavation after Netzer's death, still believes it is Herod's tomb.

The Israel Nature and Parks Authority and the Gush Etzion Regional Council plan to rebuild the tomb using a light plastic material. This idea has received strong criticism from many Israeli archaeologists.

How People Remember Herod

Historians say that Herod the Great "is perhaps the only figure in ancient Jewish history who has been disliked equally by Jewish and Christian people." Both Jews and Christians often describe him as a tyrant and a cruel ruler.

Herod's religious policies received mixed reactions from the Jewish people. Even though Herod saw himself as king of the Jews, he also showed that he represented non-Jews in Judea. He built temples for other religions outside the Jewish areas of his kingdom.

However, Herod was also praised for his work. He is considered the greatest builder in Jewish history. He was seen as someone who "knew his place and followed the rules." What remains of his building projects are now popular tourist attractions in the Middle East. Many people value them as both historical and religious sites.

Images for kids

-

Distinctive Herodian masonry at the Western Wall in Jerusalem

-

The Division of Herod's Kingdom: Territory under Herod Archelaus Territory under Herod Antipas Territory under Philip the Tetrarch Jamnia under Salome I.

-

Herod's sarcophagus, displayed at the Israel Museum

-

Bronze coin of Herod the Great, minted at Samaria.

See also

In Spanish: Herodes I el Grande para niños

In Spanish: Herodes I el Grande para niños