Military history of the Neo-Assyrian Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Assyrian Army |

|

|---|---|

Assyrian soldiers, from a plate in THE HISTORY OF COSTUME by Braun & Schneider (c. 1860).

|

|

| Leaders | King of Assyria |

| Dates of operation | 911 BC – 605 BC |

| Headquarters | Kalhu (Nimrud), Assur, Nineveh, Harran, Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad) |

| Active regions | Mesopotamia, parts of the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt and western Persia |

| Size | capable of 300,000+ men |

| Part of | Assyrian Empire |

| Opponents | Babylon, Elam, Media, Egypt, Urartu, Archaic Greece, Arameans, Arabs, Scythia, Persia, Cimmeria, Mushki, Israel, Neo-Hittites |

The Neo-Assyrian Empire grew strong in the 10th century BC. King Ashurnasirpal II was known for his smart war plans. He wanted to protect his borders and also gain wealth. He would raid lands far away, especially in the Levant, to get resources. This way, the wealth from these areas helped power the Assyrian army.

After Ashurnasirpal II, Shalmaneser III became king. He fought wars for 31 of his 35 years as ruler. But he did not conquer as much land as Ashurnasirpal II. When he died, Assyria became weak again.

Assyria got strong once more under Tiglath-Pileser III. His changes made Assyria the most powerful force in the Near East. It became the first true empire of its kind. Later kings like Shalmaneser V, Sargon II, and Sennacherib continued to attack enemies. Their goal was not just to conquer, but to stop enemies from challenging Assyrian power. These battles were tough and cost many Assyrian soldiers. Esarhaddon conquered lower Egypt. His son, Ashurbanipal, then took the southern part of Egypt.

However, by the end of Ashurbanipal's rule, the Assyrian Empire seemed to be weakening. It never fully recovered. Many costly battles and constant rebellions likely used up too many soldiers. When outer regions were lost, foreign troops also left. By 605 BC, records of the Neo-Assyrian Empire disappear from history.

Contents

How the Assyrian Army Grew

The Assyrian Empire is often called the "first military superpower in history." Mesopotamia was where some of the earliest battles ever recorded happened. For example, the first known battle was between Lagash and Umma around 2450 BC. The ruler of Lagash, Eanatum, was said to be inspired by a god to attack Umma. Even though Eanatum won, he was hit in the eye by an arrow. He set up the Stele of the Vultures to celebrate his victory.

The Middle Assyrian Period

Under kings like Shamshi-Adad I (1813–1791 BC) and Ishme-Dagan (1790–1754 BC), Assyria became a strong regional empire. It controlled northern Mesopotamia and parts of Asia Minor and Syria. From 1365 to 1076 BC, Assyria grew into a major world power, as strong as Egypt. Kings such as Ashur-uballit I and Tiglath-Pileser I built an empire. At its largest, it stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the Caspian Sea. It also reached from the Caucasus mountains to Arabia.

The 11th and 10th centuries BC were a difficult time for the whole Near East. There were many changes and large movements of people. Despite this, Assyria remained a strong nation with good defenses. Its warriors were considered among the best. Assyria had a stable government and secure borders. This made it stronger than rivals like Egypt, Babylonia, and Elam.

It is hard to find much information about the Assyrian army during this time. The Assyrians gained their independence twice. This happened during the Old Assyrian Empire and the Middle Assyrian Empire. The Middle Assyrian Empire even reached Babylon in its conquests. However, armies were mostly made up of farmers. These farmers would fight for the king after planting their fields. They had to return home for harvest time. This meant that military campaigns only lasted a few months each year. Armies could not conquer huge areas without resting. They also could not keep many soldiers in conquered lands for long.

How the Military Was Organized

The Assyrian army's structure was like other armies in Mesopotamia at that time. The King, believed to be chosen by the gods, was the top commander. He would sometimes pick senior officers to lead campaigns in his place. The Neo-Assyrian Empire used many different types of military tools and machines. These included chariots, cavalry (soldiers on horseback), and siege engines.

Before the Big Changes

Before Tiglath-Pileser III made his changes, the Assyrian army was similar to other Mesopotamian armies. Most soldiers were farmers. They had to go back to their farms for harvest. Only a few professional soldiers existed. These were bodyguards for the King or other important people. They were not usually sent into battle unless it was an emergency.

Assyrian armies could be very large. Shalmaneser III once said he had 120,000 men for his campaigns in Syria. To get so many men, soldiers were taken from conquered peoples. A large army also needed a lot of food and supplies. The Assyrians planned for these needs before they started a campaign.

Getting Ready for a Campaign

To prepare for a new campaign, troops first gathered at a special base. In Assyria, these places included Nineveh, Kalhu, or Khorsabad. Sometimes, the meeting points changed based on the campaign's target. Governors were told to gather grain, oil, and war material. They also had to call up the needed soldiers. Vassal states (kingdoms under Assyrian rule) had to provide troops as a tax to the Assyrian king. If they failed to do so, it was seen as an act of rebellion.

When the King and his bodyguards arrived, the army would begin its march. The army marched in good order. The standards of the Gods came first, showing that the Assyrian Kings served their main God, Assur. Next came the King, surrounded by his bodyguards. Behind them were the main chariot and cavalry divisions, who were the army's best fighters. In the back was the infantry (foot soldiers). First came the Assyrian troops, then soldiers from conquered lands. After them were the siege train (machines for attacking cities), supply wagons, and then camp followers. This formation would have been weak to an attack from the rear. Some groups of soldiers could march 30 miles a day. This speed helped to surprise and scare enemies into giving up.

Tiglath-Pileser III's Army Reforms

Soon, the Assyrian army's weaknesses became clear. Many soldiers died in battles. Also, the changing seasons meant soldiers had to return to their farms. This stopped them from making big conquests. By the mid-8th century BC, the Assyrian army, made of farmers, could not handle the needs of a huge empire. This empire often stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the Persian Gulf.

Everything changed when Tiglath-Pileser III became king in 745 BC. He made the Assyrian government more efficient. Then, he changed the army. The most important change was creating a standing army. This army had more foreign soldiers mixed with Assyrian soldiers. These foreign soldiers could be given by vassal states as tribute or when the King asked. They received Assyrian equipment and uniforms. This made them look the same, perhaps to help them fit in. The foot soldiers in the standing army had many foreigners, including Aramaeans and even Greeks. However, Assyrian cavalry and charioteers were still mostly Assyrians. There were some exceptions. As more soldiers were lost, extra troops were welcome. Sargon II said he added 60 Israelite chariot teams to his army.

Travel and Communication

As the Assyrian Empire grew, new ways of travel and communication were needed. Before the Neo-Assyrian Empire, roads in Mesopotamia were just paths. But this was not enough for an empire whose armies were always moving. The Assyrians were the first to build and keep up a system of roads across their empire. They set up a state communication system. It had regular stations where messengers could rest or change horses. Later, the Persians used this system as a base to build their own empire's roads.

They cut through rough mountains, which made travel much faster. Engineers built nice stone paths leading to the great cities of Assur and Nineveh. This was to impress foreigners with Assyria's wealth. By 2000 BC, wooden bridges were built across the Euphrates. By 1000 BC, Nineveh and Assur had stone bridges. This showed how rich the kingdom of Ashur was. Building roads and improving transport meant that goods could move more easily. This helped supply the Assyrian war effort. Of course, roads that sped up Assyrian troops also sped up enemy troops.

Using Camels

The Assyrians were the first to use camels to carry supplies for their military campaigns. Camels were more useful than donkeys. They could carry five times more weight but needed less water. Camels were not tamed until just before 1000 BC, around the time the Neo-Assyrian Empire began. The first camel to be tamed was the dromedary.

Wheeled Vehicles

The Sumerians are usually given credit for inventing the wheel before 3000 BC. However, some evidence suggests it might have come from the Black Sea region of Ukraine. The Assyrians were the first to make metal tires for wheels. These were made from copper, bronze, and later iron. Metal-covered wheels were much stronger and lasted longer.

Weapons Used by Soldiers

- Spears: These had a wooden shaft and a sharp iron tip. They were about 5 feet long.

- Iron swords: Used for close-up fighting.

- Daggers: Smaller knives for combat.

- Javelins: Lighter spears thrown from a medium distance to break shields.

- Slings: Used to throw stones at enemies from a distance.

- Bow and arrow: A long-range weapon for attacking from far away.

Chariots in Battle

Chariots were a very important part of the Assyrian army. They were fast and could move easily. Chariots were used to attack the enemy's sides, making them break apart or run away. Chariots usually had two or three horses, a platform with two wheels, and two soldiers. One soldier steered the horses, while the other shot arrows at enemy troops. Chariots worked best on flat battlegrounds.

Ancient Egyptians and Sumerians also used war chariots. They used them as moving platforms for shooting or as mobile command posts. From a chariot, a general could see how the battle was going. Because chariots were fast, they were also used to send messages on the battlefield. They were also a fancy way for Assyrian kings to show their wealth and power.

However, as cavalry (soldiers on horseback) became more common in the 1st millennium BC, chariots changed. By the 7th century BC, chariots were mainly used for fighting. Lighter chariots with two or three horses were later made heavier under King Ashurbanipal. These new chariots had four horses and could carry up to four men. Heavier chariots also had new jobs. They would crash into enemy lines, scattering the foot soldiers. The Assyrian cavalry and infantry could then attack the gaps and defeat the enemy, taking control of the battlefield.

Cavalry: Soldiers on Horseback

The use of cavalry came about because the Assyrians fought different enemies in rough, mountainous areas. Chariots could not work well on uneven ground. So, a new way of fighting was needed. Cavalry units were like the chariot corps. They were a scary, well-armored, elite group of soldiers who could control the battlefield. Cavalry soldiers had light armor, spears or lances, and bows and arrows.

In the 9th century BC, cavalry units worked much like chariots. Two horses carried two soldiers. One soldier controlled the reins, while the other used a ranged weapon. Over almost two centuries, the Assyrians became very skilled with cavalry. But they faced some problems. Horse archers could not use their bows and hold the reins at the same time. So, cavalry under Ashurnasirpal are shown in pairs. One rider held both reins, and the other shot with a bow.

The Assyrians had fewer problems when cavalry were used as lancers (soldiers with long spears). Under Tiglath-Pileser III, Assyrian cavalry still rode in pairs. But this time, each warrior held his own lance and controlled his own horse. By the 7th century BC, mounted Assyrian warriors were well-armed with a bow and a lance. They wore lamellar armour, and their horses had fabric armor. This gave them some protection in close combat and against arrows. Cavalry became the main part of later Assyrian armies. Cavalry could dominate battles. But their weakness when trying to break enemy lines was long spears. Long spears could stop cavalry from a safe distance, letting enemy troops hold their ground.

Cavalry were rarely used by the Assyrians or other Mesopotamians until the 9th century BC. Their use is first mentioned during the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta II. Before then, many nomads or steppe warriors who raided Assyrian lands used cavalry. The Assyrians had to find a way to fight this fast style of warfare. So, they learned to beat their opponents, especially the Iranians, at their own game. The Iranian Medes likely had a big influence. Their raids helped Assyria build a cavalry army to destroy the Kingdom of Elam.

The Assyrians needed large cavalry units. Some units had hundreds or even a thousand horsemen. Without a steady supply of horses, the Assyrian war machine would have failed. As the empire lost many soldiers in Ashurbanipal's conquests, the rebellions after his death might have led to the empire's fall. Fewer vassal states were available to provide horses and other war materials. Horses were a very important war resource. The Assyrian king himself made sure there was a good supply of horses. Horses came from three main sources:

- Raids to steal horses from enemies, like the Scythians.

- Tribute paid by vassal states.

- High-ranking state officers who managed horse production and reported to the King.

Horses were brought from distant provinces and trained with new recruits for war.

Infantry: Foot Soldiers

While cavalry were expensive and elite, infantry were cheaper and more numerous. Often, they were also more effective, especially in siege warfare. In sieges, the speed of horsemen was not useful. Assyrian infantry included both native Assyrians and foreigners. They served as auxiliaries, spearmen, slingers, shield bearers, or archers. Archers were the most common in Assyrian armies.

From the time of Ashurnasirpal, archers had a shield bearer with them. Slingers might have tried to make the enemy lower their shields to protect against stones. This would allow archers to shoot over their shield walls and hit enemies. Even in siege warfare, arrows were used to push defenders away from the wall. This allowed engineers to move forward against the city's defenses.

The Assyrians used many different types of bows. These included Akkadian, Cimmerian, and their own "Assyrian" type. However, these were likely just different versions of the powerful composite bow. Depending on the bow, an archer could shoot anywhere from 250 to 650 meters. Many arrows were used in battle. So, many arrows were made before a war. There were also places that traveled with the army's supplies to make more arrows during a campaign.

Lancers (infantry with lances) were added under Tiglath-Pileser III. Pictures of infantry with special bronze scale metal protection are rare. Reconstructions show that even the smallest vests weighed about 20 pounds (9 kg). Full armored suits reaching the ankles could weigh three times that amount in metal and leather.

War Plans and Battle Moves

Battle Tactics

Assyrian frontal assaults were meant to shock and surprise the enemy. But they were also used when there was no time to plan:

The tired troops of Ashur, who had come a long way, very weary, slow to respond, who had crossed and re-crossed countless steep mountains, very hard to climb up and down, their spirits turned rebellious. I could not ease their tiredness, nor give water to quench their thirst; I could not set up a camp, nor build defenses

—Sargon II

Despite these problems, Sargon II's quick thinking saved the day. He led his exhausted troops in a surprise attack against his Urartian enemies. The Urartians broke because of the speed and surprise of the attack. The battle was so fierce that the Urartian King left behind his officials, governors, 230 royal family members, many cavalry and infantry, and even the capital city itself.

Overall War Strategy

Mesopotamia was a flat, fertile land with few natural defenses. This meant that defending was hard. Only a strong attack could protect these valuable places. The cities of Assur and Nineveh were both located between rivers. Nineveh was more protected by the Tigris river. Assur was close to the Tigris but far from the Euphrates. So, both cities had some natural protection. However, rivers would not stop a determined army. Therefore, attacking and destroying their enemies' ability to fight was the best way to keep Assyria safe. To do this, the Assyrians aimed for a decisive battle that would crush their enemies' armies.

Settling New Lands: The Assyrians also sent some of their own people into foreign lands to live there as colonists. Their main goal was to create a loyal power base. Taxes, food, and troops could be gathered from these areas as reliably as from their homeland. Also, their presence would bring many benefits. They could resist other conquerors, help stop native rebellions, and assist Assyrian governors in keeping vassal states loyal.

Destroying Cities: We should be careful before saying the Assyrians used "total war." However, it is known that the Assyrians would violently destroy what they could not take or hold. This was part of their plan to weaken enemies and get revenge. About the Assyrian conquest of Elam, Ashurbanipal wrote:

For a distance of a month and twenty-five days' journey I devastated the provinces of Elam. Salt and sihlu I scattered over them... The dust of Susa, Madaktu, Haltemash and the rest of the cities I gathered together and took to Assyria... The noise of people, the tread of cattle and sheep, the glad shouts of rejoicing, I banished from its fields. Wild asses, gazelles and all kinds of beasts of the plain I caused to lie down among them, as if at home.

—Ashurbanipal

Psychological Warfare

The Assyrians understood how to use fear to control their enemies. To save soldiers and quickly deal with problems, the Assyrians preferred enemies to surrender. If not, they would destroy their ability to fight back. This helps explain their attacking strategies and tactics.

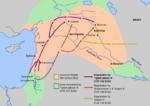

Mass Movements of People

It is not known if the Assyrians were the first to move large groups of people. But since no one before them ruled the Fertile Crescent as they did, they likely were the first to do it on a large scale. The Assyrians began using mass-deportation as a punishment for rebellions in the 13th century BC. The reasons for moving people included:

1) Scaring Enemies: The idea of being moved would have terrified people. 2) Mixing People: Having many different groups of people in each region would have reduced strong national feelings. This made ruling the Empire smoother. 3) Saving People: Instead of being killed, people could work as laborers or soldiers in the army.

By the 9th century BC, the Assyrians regularly moved thousands of rebellious people to other lands. Moving these people to the Assyrian homeland would have weakened the empire if they rebelled again. So, Assyrian deportation involved moving one enemy group and settling them among another. Here are some examples of people moved by Assyrian Kings:

- 744 BC: Tiglath Pileser III moved 65,000 people from Iran to the Assyrian-Babylonian border.

- 742 BC: Tiglath Pileser III moved 30,000 people from Hamath, Syria, to the Zagros mountains.

- 721 BC: Sargon II (he claimed) moved 27,290 people from Samaria, Israel. He spread them throughout the Empire. However, his dead predecessor, Shalmaneser V, likely ordered this.

- 707 BC: Sargon II moved 108,000 Chaldeans and Babylonians from the Babylonian region.

- 703 BC: Sennacherib moved 208,000 people from Babylon.

Tiglath Pileser III brought back large-scale deportations. He moved tens, even hundreds of thousands of people. These movements were also combined with settling new lands, as mentioned before.

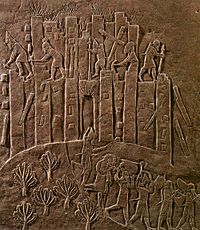

Siege Warfare: Attacking Cities

In 647 BC, the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal destroyed the city of Susa. This happened during a war where the people of Susa had sided with Assyria's enemies. A clay tablet found in 1854 by Austen Henry Layard in Nineveh shows Ashurbanipal as an "avenger." He sought revenge for the insults the Elamites had caused Mesopotamians over centuries. Ashurbanipal described Assyrian revenge after his successful attack on Susa:

Susa, the great holy city, home of their gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were gathered... I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I turned the temples of Elam to nothing; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their old and new kings I ruined, I exposed them to the sun, and I carried their bones to the land of Ashur. I destroyed the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt.

—Ashurbanipal

The flat, fertile lands of Mesopotamia were good for warfare and also attracted wars. Raiders from many nations wanted Assyrian lands. These included Scythians from the north, Syrians, Arameans, and Cimmerians from the west. Elamites were to the east, and Babylonians to the south. The Babylonians, in particular, often rebelled against Assyrian rule.

To protect settlements from chariots and cavalry, walls were built. These were often made of mud or clay because stone was expensive and hard to find. To defeat their enemies, these cities had to be captured. So, the Assyrians became masters of siege warfare. Esarhaddon claimed to have captured Memphis, the capital of Egypt, in less than a day. This shows how fierce and skilled Assyrian siege tactics were at this time:

I fought daily, without stopping, against Taharqa, King of Egypt and Ethiopia, who was cursed by all the great gods. Five times I hit him with my arrows, wounding him so he would not recover. Then I laid siege to Memphis, his royal home, and conquered it in half a day using mines, breaches, and assault ladders

—Esarhaddon

Sieges cost many soldiers, especially if an attack was launched to take the city by force. The siege of Lachish cost the Assyrians at least 1,500 men. Their bodies were found in a mass grave near Lachish. Before standing armies, a city's best hope was that the harvest would force the enemy to return to their fields. This would make them abandon the siege. However, with Tiglath Pileser III's reforms, Assyria had its first standing army. This army could blockade a city until it surrendered. Still, Assyrians always preferred to take a city by direct attack rather than a long blockade. An attack would be followed by killing or moving the people. This would scare other enemies of Assyria into surrendering.

Siege Weapons

The simplest and cheapest siege weapon was the ladder. But ladders are easy to knock over. So, the Assyrians would shoot many arrows at their enemies to provide cover. These archers were protected by shield bearers. Other ways to weaken enemy defenses included mining. A 9th-century Assyrian carving shows soldiers using ladders to climb walls. Others use spears to scrape mud and clay from the walls. A soldier is also shown under a wall. This suggests that mining was used to dig under foundations and make walls fall.

The battering ram seems to be one of the best Assyrian inventions for siege warfare. They were like a tank, with a wooden frame on four wheels. There was a small tower on top for archers to shoot from as the machine moved forward. When it reached the wall, its main weapon, a large spear, was used to smash and chip away pieces of the enemy wall. This would not have worked well against stone walls. But most walls were made of mud, not stone. Even when dry, these mud walls could be attacked with such machines. Walls were made stronger over time. The Assyrians responded by building larger machines with bigger "spears." Eventually, they looked like a large, long log with a metal tip. Even stone would not stand up to pounding by a larger weapon. Bigger machines held more archers. To protect against fire (which both sides used at the Siege of Lachish), the battering ram was covered in wet animal skins. These could be watered during battle if they dried out.

I captured 46 towns... by building ramps to bring up battering rams, by infantry attacks, mines, breaches and siege engines

—Sennacherib

Siege towers, even ones that could float, were used when a wall faced a river.

- Video on The Assyrian assault on Lachish and a water tunnel in Jerusalem.

Key Dates in Assyrian Military History

3rd and 2nd Millennia BC

- 2340–2284 BC Sargon of Akkad conquered much of Mesopotamia.

- 1230 BC Battle of Nairi took place.

- 1170 BC Nineveh reached its greatest power and influence.

9th Century BC

- Cavalry use was first recorded by Tukulti Ninurta II.

- 883 BC Ashurnasirpal II became king and began expanding Assyria.

- 877 BC Ashurnasirpal II led Assyrian troops to the Mediterranean and Mount Lebanon for the first time.

- 858 BC Shalmaneser III made Bit Adini a vassal state.

- 853 BC After taking Aleppo, Shalmaneser III was stopped at the Battle of Qarqar.

- 851 BC Shalmaneser III defeated a Chaldean revolt in Babylon.

- 849, 845 and 841 BC Shalmaneser III tried three times to take Syria but failed.

- 840 BC Shalmaneser III failed to defeat Urartu.

- 832 BC Shalmaneser III failed to capture Damascus in a siege.

- 824 BC Shalmaneser III died, and Assyria entered a period of weakness.

8th Century BC

- 780–756 BC Argistis I ruled Assyria. Lake Urmia was lost to Urartu.

- 745 BC Tiglath Pileser III took power in a coup; the Assyrian Army was reformed.

- 744 BC Tiglath Pileser III moved many Iranians.

- Unknown date: Tiglath Pileser III defeated Babylon.

- 743 BC Tiglath Pileser III decisively defeated Urartu and besieged Arpad.

- 741 BC Arpad fell to Tiglath Pileser III.

- 734–732 BC Syro-Ephraimite War: Rebellions in Syria and Palestine were crushed. Damascus fell in 732 BC.

- 732 BC Babylon was conquered by Assyria after a Chaldean took the throne. Lands around Babylon were destroyed during three years of fighting.

- 724–722 BC Shalmaneser V besieged and then captured Samaria.

- 721 BC A coup by Sargon II led to the Samaria revolt; it was quickly crushed.

- 721 BC Sargon II defeated a Babylonian rebellion.

- 717–716 BC Sargon II took Carchemish to secure trade routes in the north.

- 714 BC A major military disaster hit Urartu; Sargon II destroyed Urartu's ability to fight forever.

- 713 BC Rumors of an anti-Assyrian alliance led Sargon II to take Tabal.

- 710–707 BC Another Babylonian revolt was crushed by Sargon II.

- 709 BC Assyrian forces sent by Sargon II forced Midas to seek peace.

- 703 BC Another Chaldean-backed Babylon revolt was crushed by Sennacherib, just one year after he became king.

- 701 BC Sennacherib moved down the Mediterranean coast to control Syria and Israel. Lachish was taken after bloody fighting, while Egyptian aid was pushed back. The Siege of Jerusalem failed.

7th Century BC

- 694 BC Sennacherib attacked Elam. Elam attacked Babylon, which was then unguarded by the Assyrian army.

- 693 BC Battle of Diyala River: Assyrian attack on Elam was called back due to a Babylonian revolt.

- 692 BC Battle of Halule: An alliance of Elamites, Babylonians, Chaldeans, and Aramaic and Zagros tribes fought off the Assyrians.

- 691 BC Sennacherib won a costly victory against Elam. However, he crushed the Babylon revolt.

- 681 BC Sennacherib was murdered by two of his sons; another son Esarhaddon got revenge and ruled Assyria.

- 679 BC An alliance of Cimmerians and Scythians was defeated by Esarhaddon's forces.

- 679 BC Esarhaddon's troops took Arzani and reached the Egyptian border.

- 676 BC Esarhaddon launched an attack to counter growing Iranian power.

- 675 BC An attack on Egypt was pushed back.

- 671 BC Another Assyrian attack into Egypt was a success.

- 669 BC Memphis was sacked by Assyrian troops.

- 668 BC Ashurbanipal became king after Esarhaddon. He was the last King of Assyria to expand its borders beyond Mesopotamia.

- 665 BC A ten-year campaign against Media began.

- 665 BC Elam attacked Babylon, but failed.

- 663 BC Ashurbanipal lifted an Egyptian siege of Memphis and destroyed Thebes in the south.

- 655 BC Elam attacked Babylon. At the same time, Egypt launched another attack. The Elamite attack was stopped by a large Assyrian army gathered by Ashurbanipal.

- Unknown date (possibly 655 BC) Ashurbanipal drove Elamite forces across the River Ulai in the plain of Susa.

- 653 BC Median invasion was stopped by a Scythian attack.

- 652 BC Babylon revolted again.

- 651 BC Ashurbanipal left Egypt to focus on Elamite attacks; the Assyrian army showed signs of being spread too thin.

- 648 BC Babylon was completely destroyed by Assyria; Elamite civil war meant no help from Elam.

- 647 BC Battle of Susa: Susa was completely destroyed by Ashurbanipal.

- 639 BC Ashurbanipal devastated the lands of Elam. The Elamite kingdom never recovered.

The Fall of Assyria

- 635 BC Egypt, unchecked since 651 BC, stormed Ashdod.

- 627 BC Ashurbanipal died. The fall of Assyria sped up.

- 622 BC An Assyrian expedition may have been launched west of the Euphrates; lack of Assyrian records suggests a likely Assyrian defeat.

- 616 BC Nabopolassar, King of Babylon since 626 BC, drove out Assyrian troops from Babylonia.

- 615 BC Median invasion of Assyria resulted in the capture of Arrapha.

- 614 BC Assur, the first capital of Assyria, was sacked by the Medes under King Cyaxares.

- 612 BC Battle of Nineveh (612 BC): Nineveh was destroyed by an alliance of Medians and Babylonians after only a 3-month siege.

- 609 BC Battle of Megiddo (609 BC): Egyptians unsuccessfully tried to help the Assyrians.

- 609 BC Fall of Harran: The newly established Assyrian capital at Harran was destroyed by pursuing Median and Babylonian forces.

See also

- Ancient warfare

- Assyrian Levies

- List of artifacts significant to the Bible

- Military history of Egypt

- Military history of Iran

- Military history of Iraq

- Syro-Ephraimite War

- Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |