Old Assyrian period facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Old Assyrian period

ālu Aššur

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2025 BC–c. 1364 BC | |||||||||

| Capital | Assur | ||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian, Sumerian and Amorite | ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Notable kings | |||||||||

|

• c. 2025 BC

|

Puzur-Ashur I (first) | ||||||||

|

• c. 1974–1935 BC

|

Erishum I | ||||||||

|

• c. 1920–1881 BC

|

Sargon I | ||||||||

| Legislature | Ālum | ||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||

|

• Assur becomes independent from the Third Dynasty of Ur

|

c. 2025 BC | ||||||||

|

• Conquest by Shamshi-Adad I

|

c. 1808 BC | ||||||||

|

• Collapse of Shamshi-Adad's kingdom

|

c. 1776–1765 BC | ||||||||

|

• Foundation of the Adaside dynasty

|

c. 1700 BC | ||||||||

|

• Subjugation under Mitanni

|

c. 1430–1360 BC | ||||||||

|

• End of the reign of Eriba-Adad I

|

c. 1364 BC | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

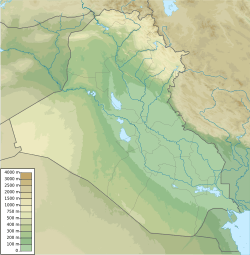

| Today part of | Iraq | ||||||||

The Old Assyrian period was an important time in the history of Assyria. It covers the period when the city of Assur became an independent city-state around 2025 BC. This era ended around 1363 BC when Assyria grew into a larger kingdom. This period saw the start of a unique Assyrian culture, different from other parts of Mesopotamia.

During this time, Assur was often a small city-state. Its leaders were called Išši'ak Aššur, meaning "governor of the god Ashur", not "king". They worked with a city assembly called the Ālum, made up of important citizens. Even though Assur wasn't a military superpower, it became a major trading hub. From about 1974 BC, it was part of a huge trade network. This network stretched from the Zagros Mountains to central Anatolia. Assyrian traders even set up colonies, like the one at Kültepe.

The first Assyrian royal family, started by Puzur-Ashur I, ended around 1808 BC. This happened when the city was taken over by Shamshi-Adad I, an Amorite ruler. He created a short-lived kingdom called the Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia. After his death around 1776 BC, there was a period of conflict. Assur eventually became independent again around 1700 BC under the Adaside dynasty. Later, around 1430 BC, Assur became a vassal (a state controlled by another) of the Mitanni kingdom. However, it broke free in the early 14th century BC. This led to Assyria becoming a powerful territorial state.

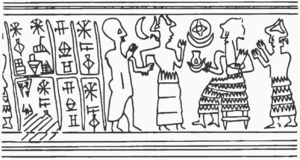

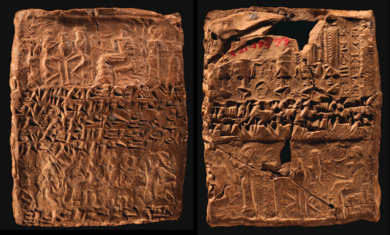

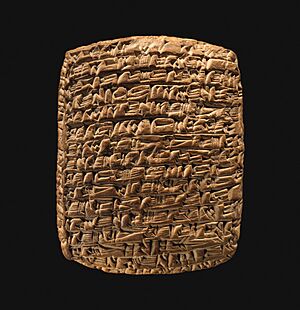

We know a lot about the Old Assyrian period from over 22,000 clay tablets. These tablets were found at the trading colony in Kültepe. They tell us about their culture, language, and society. Like many ancient societies, they had slaves. Men and women had similar legal rights. They could own property, make wills, and even start divorce proceedings. The main god they worshipped was Ashur, who was also the name of their city.

Contents

What is Old Assyrian?

Historians divide ancient Assyrian history into different stages. "Old Assyrian" is one of these stages. It describes the earliest time when we have enough information to call the culture "Assyrian." This term refers to the city of Assur and its unique culture. It covers its history, politics, economy, religion, and language. Assur was much older than this period, but before it, it wasn't an independent city.

History of Assur

Early Kings and Trade

Assur likely became an independent city-state under Puzur-Ashur I around 2025 BC. We don't know much about how he came to power. His family said he rebuilt the city walls. Assur became independent when the Third Dynasty of Ur in the south lost control. Not many old buildings from Assur survive from this time. Most records talk about building projects.

Puzur-Ashur and his family didn't call themselves "kings." They used the title Išši'ak, meaning "governor." They believed the god Ashur was the true king. Assur was a small city then, with only about 5,000 to 8,000 people. It didn't have a strong army or control other cities.

Shalim-ahum, Puzur-Ashur's son, built a temple for Ashur. His son, Ilu-shuma, was the first Assyrian king to get involved in foreign trade. He claimed to have opened trade with southern Mesopotamia, selling copper. This shows Assur was producing a lot of copper. Ilu-shuma also built wells for water and brick-making.

His son, Erishum I (around 1974–1934 BC), was even more successful. He started a system of free trade. Private bankers funded trade, taking most of the risks and profits. Assur quickly became a major trading city. Erishum earned money from tolls, which he used to expand Assur. He rebuilt Ashur's temple and built a new one for the god Adad.

Ikunum (around 1934–1921 BC), Erishum's son, rebuilt the city walls. This project needed money from Assur and its trading colonies. His son, Sargon I (around 1920–1881 BC), had a very successful reign. Assyrian trade reached its highest point. However, later kings faced threats from foreign enemies.

Trading Posts and Networks

Even though we have few records from Assur itself, we have many from Kültepe in central Anatolia. Kültepe, also known as Kanesh, was a city-state with its own kings. Assyrians set up a trade colony, or karum, there. Archaeologists found about 22,000 cuneiform clay tablets in Kültepe. These tablets show a huge Assyrian trade network. Assur was the center of this network.

Historians once thought these tablets meant Assyria had a large empire in Anatolia. But now, they believe it was a trade network, not an empire. Assyrian traders lived in Kültepe, but their homes looked like local ones. This suggests they lived as foreign residents, not as conquerors. The colony was also a place for making pottery and metal objects.

The Assyrians in Kültepe had their own government and court. They followed Assyrian law and often got orders from Assur. The tablets also show how traders communicated with their wives back home. Wives often helped gather materials for trade.

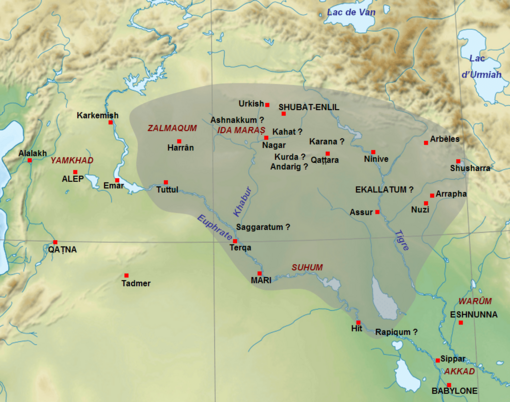

Around 1836 BC, the Kültepe colony was burned down, which helped preserve the tablets. It was rebuilt soon after. During this time, about 25 tons of silver went to Assur from Anatolia. In return, about 100 tons of tin and 100,000 textiles went to Anatolia. Assyrians also sold livestock and other goods. Many goods came from far away, like textiles from southern Mesopotamia and tin from the Zagros Mountains.

A trip between Assur and Kültepe (about 1,000 km or 620 miles) took six weeks by donkey caravan. Traders paid taxes along the way, but their profits were huge. They often sold goods for double the price they paid in Mesopotamia. Assur's importance as a trade center declined in the 19th century BC. This was likely due to more conflicts between states, which reduced overall trade.

Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia

From the 19th century BC, Assur often came under the control of larger foreign states. A lot of information from this time comes from records found in Mari. This period includes the rule of Shamshi-Adad I (around 1808–1776 BC) and his sons. Shamshi-Adad was an Amorite king from Ekallatum. Around 1808 BC, he took over Assur, removing the last king of Puzur-Ashur I's family.

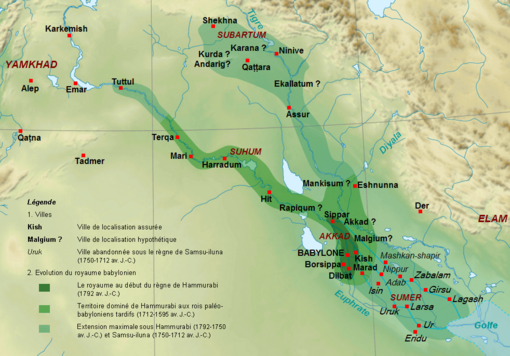

Shamshi-Adad then conquered many cities, including Mari. His kingdom, sometimes called the Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia, covered most of northern Mesopotamia. He made Shubat-Enlil his capital. He put his sons in charge of different parts of the kingdom. His elder son, Ishme-Dagan, ruled Ekallatum and Assur.

Under Shamshi-Adad, Assur remained a distinct city and continued trading. Shamshi-Adad rebuilt temples in Assur, showing respect for the city. However, he was a foreign ruler and kept his capital elsewhere. Assur's strong city assembly might have made it less appealing as a main capital.

Kingdom's Collapse and a "Dark Age"

Shamshi-Adad's kingdom was surrounded by powerful rivals. Its survival depended on his military success. When he died around 1776 BC, his kingdom quickly fell apart. Local rulers regained power. His son, Ishme-Dagan, only kept control of Ekallatum and Assur.

Around 1772 BC, Eshnunna invaded Ishme-Dagan's kingdom, taking Assur. Ishme-Dagan fled to the Old Babylonian Empire. He later returned with help from Babylon. Northern Mesopotamia was invaded again by an army from Elam. This invasion was pushed back by an alliance. Assur eventually came under the control of the Old Babylonian Empire under Hammurabi around 1761 BC. Hammurabi respected Assur's traditions.

The time after Shamshi-Adad's kingdom fell until the 14th century BC is often called an Assyrian "Dark Age." This is because we have very few historical records from this period. It seems Assur became an independent city-state again at some point. The Assyrian King List names a continuous line of rulers, but it might not be fully accurate for this uncertain time. Different groups fought for control of Assur.

Around 1700 BC, Bel-bani founded the Adaside dynasty. This family ruled Assyria for about a thousand years. Later Assyrian kings looked up to Bel-bani as a restorer of peace. The Assyrian King List is considered more reliable for the kings from Bel-bani onwards.

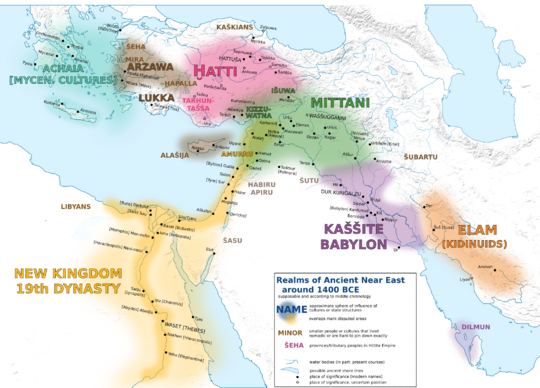

Rise of Assyria

A major event for Assyria was the invasion of Mesopotamia by the Hittite king Mursili I around 1595 BC. This destroyed the Old Babylonian Empire, creating a power vacuum. This led to the rise of the Kassite kingdom in the south and the Hurrian Mitanni state in the north. Assur also became more prominent during this time.

Assyrian rulers from about 1520 to 1430 BC were more assertive. Puzur-Ashur III (around 1521–1498 BC) was the first Assyrian king mentioned in a text about border disputes with Babylonia. This suggests Assyria was starting to deal with other major powers. Assyrian kings also exchanged gifts with Egyptian pharaohs.

Assur was prosperous from the late 16th to early 15th century BC. Kings like Puzur-Ashur III repaired and expanded many city buildings. The city walls were extended, showing a growing population. A "new city" was added to the "inner city."

Around 1430 BC, Assur became a vassal of Mitanni for about 70 years. Assyrian kings still had some freedom. They built projects, traded with Egypt, and signed agreements. The Mitanni kingdom weakened due to wars with the Hittites. This allowed Assyria to break free.

Assyria's independence came under King Ashur-uballit I (around 1363–1328 BC). He conquered nearby lands, marking the start of the Middle Assyrian period. Ashur-uballit I was the first native Assyrian ruler to call himself "king." He even claimed to be a "great king," like the pharaohs and Hittite kings.

Daily Life and Society

Population and Culture

Unique burial practices in Assur suggest a distinct Assyrian identity formed early on. Frequent contact with foreigners through trade might have strengthened this identity. An old rule stated that "Assyrians can sell gold among each other but... no Assyrian... shall give gold to an Akkadian, Amorite or Subaraean." This shows Assyrians saw themselves as a separate group.

Men and women in Old Assyrian society had similar legal rights. They could inherit property, trade, own houses and slaves, make wills, and divorce. Society was divided into two main groups: slaves (subrum) and free citizens (awīlum or "sons of Ashur"). Among free citizens, there were "big" and "small" members of the city assembly.

Old Assyrian Families

Marriages were usually arranged by the groom's family and the bride's parents. They often happened when the bride became an adult. Gifts were common, and engagements could be broken if no gifts were given. The bride's dowry belonged to her and was passed to her children. Wives moved in with their husbands, who provided them with clothes and food.

Most marriages were monogamous (one husband, one wife). If a wife couldn't have children after two or three years, a husband could buy a female slave to have heirs. This slave was not considered a second wife. Families sometimes hired wet nurses to care for babies. If a mother died, other family members, like grandparents, took care of young children.

Boys and girls were raised differently. Girls stayed with their mothers, learning to spin and weave. Boys learned to read and write and often traveled with their fathers to learn trade. The oldest daughter might become a priestess for a god, which meant she couldn't marry but became financially independent.

When traders were away, their wives managed the household in Assur. They oversaw food, house repairs, and clothing for children. Sometimes, they lived with their in-laws, which wasn't always easy. Traders in Anatolia could take a second wife there. There were rules for this: the wives had to have different statuses and live in different regions. Both wives had to be provided for. Children from the second wife might have had fewer inheritance rights.

Most divorces were agreed upon by both sides. High fines for divorce (up to 5 minas of silver) had to be paid by both. Both could remarry. If a man disliked his wife, he could send her back to her family but had to pay compensation. If a wife behaved badly, the husband could take her possessions and send her away. Divorces were more common for second wives in Anatolia.

If a husband died, his children inherited his goods and cared for their mother. If there were no children, the wife kept her dowry and could remarry. If the husband had a will, his wife could also inherit. Sons were responsible for paying their father's debts before inheriting. Daughters were not responsible for debts. Both sons and daughters cared for elderly parents and arranged funerals. After death, it was believed the deceased lived as ghosts in the Ancient Mesopotamian underworld. Families honored them with prayers and offerings, often burying them under their homes.

Slavery in Old Assyria

Slavery was common in the Ancient Near East. The Akkadian word wardum was used for slaves, but it could also mean free servants or soldiers. Many people called wardum in Old Assyrian texts managed property, so they might have been free servants. However, some wardum were bought and sold. Other words for slaves also had other meanings.

There were two main types of slaves:

- Chattel slaves: These were usually foreigners, captured in war or kidnapped.

- Debt slaves: These were free people who couldn't pay their debts. Sometimes, Assyrian children were sold into slavery if their parents couldn't pay debts. Children born to slave women automatically became slaves.

Owning slaves showed wealth. A male slave cost about 30 shekels of silver, and a female slave 20 shekels. Slaves from Anatolia were cheaper than those from Mesopotamia. Both men and women owned slaves. Female slaves cleaned, cooked, and helped raise children. Some men had children with their female slaves if their wives couldn't have children. Male slaves sometimes worked in trade caravans. City institutions, like the city hall, also owned slaves for maintenance. Slaves could be sold to pay debts or taken as security for debts.

Economy and Trade

Many Old Assyrians were involved in international trade, often through family businesses. Each family member had specific tasks. The boss, usually staying in Assur, was called abum ("father"). Partners were aḫum ("brothers"), and employees were ṣūḫārū (younger family members). Businesses were called bētum ("house").

Trade involved many jobs: porters, guides, donkey drivers, agents, traders, bakers, and bankers. The eldest son often moved to Kültepe, while the father stayed home. Other sons helped transport goods. Women were important too, especially by weaving textiles that their male relatives sold. Women received payment for these textiles and could represent their husbands in deals. Sons could inherit their father's business or start their own.

Loan contracts are common among the Kültepe tablets. These were loans of silver, often with interest (30% yearly for Assyrians, higher for locals). Loans usually had to be paid back within a year.

Food and Drink

We don't have much information about what people in Assur ate. Letters mention wives buying barley and making bread and beer. Women usually prepared food. Records from Kültepe show that bread and beer were the main foods and drinks. They ate two types of bread: sourdough and plain bread. Animal fat and sesame oil were used for cooking. They used honey as a sweetener and spices like salt, cumin, coriander, and mustard.

Meat, often grilled or in stews, included sheep, oxen, pork, shrimp, and fish. Animals were often killed at home, but pre-cut meat could be bought.

Wine was a luxury drink, made from grapes in Cappadocia and other areas. When drinking beer, Assyrians often ate beer bread made from barley. Beer was consumed in specific situations, like buying an animal or crossing a river. Guards and toll officials were often paid with beer. Wine was also used in religious rituals, like swearing oaths to a god.

Language and Writing

The language in the Assyrian tablets from Anatolia is called Old Assyrian. It's a Semitic language, related to modern Hebrew and Arabic. It's a dialect of the Akkadian language, spoken in southern Mesopotamia. Ancient writers saw Assyrian and Babylonian as separate languages.

Most Old Assyrian texts are from the early part of the period, before the "Dark Age." The writing signs were simpler than later forms of the language. There were only about 150–200 unique signs, mostly for syllables. Letters sometimes have mistakes, suggesting people wrote them themselves, not professional scribes. Some letters by women show that at least some women could read and write. Old Assyrian is easier for modern researchers to read because of its simpler signs.

Calendar System

The Old and Middle Assyrian calendar had twelve months. Each month was linked to three constellations. The months had names like Ab sharrāni and Ti'inātum. Some names show the calendar's connection to stars. For example, Tanmarta was also the name for the rising of the star Sirius. The calendar likely started in autumn, when farmers plowed fields.

The calendar had some issues. An extra week, called ḫamuštum, was added to the 30-day months. An extra full month was added every four years. Also, the start of the year didn't always match the start of the eponym year (named after an official). This meant seasons slowly shifted through the months. In the 13th century BC, King Shalmaneser I had to fix the calendar to put the months back in place.

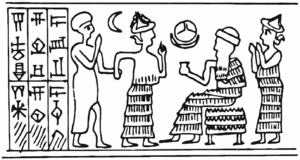

Religion and Beliefs

Assyrians worshipped the same gods as the Babylonians. Most Old Assyrian texts are about trade, so we don't know as much about their religion as in later periods. The main god was Ashur, who was also the name of their city. It's believed Ashur was a god who represented the city itself. His role changed over time. In Old Assyrian times, he was seen as a god of death, revival, and agriculture.

Ashur was also a god of justice. People believed that if you lied in court, "Ashur's dagger" would strike you down. Assyrians swore oaths on this dagger. Women swore oaths on the "tambourine (huppum) of Ishtar". These were likely physical symbols of the gods in Assur.

Ashur is often mentioned in texts. Assyrians swore oaths by "the City and the prince" or "the City and the lord," meaning Ashur. Family members in Assur would tell traders in Kültepe to "come and see the eye of Ashur." This suggests the god didn't like his people leaving the city for too long just for money. Women were very religious, making offerings and reminding their husbands of their duties to the gods.

Besides Ashur, other important gods included the weather-god Enlil and the Semitic weather-god Adad. Adad's name was part of many people's names. The moon-god Sîn was also very important. His name was also common in people's names. The goddess Ishtar was worshipped in Assur even before this period. She was probably the city's original main deity.

Few purely religious texts from this time survive. One poem describes an evil demon, the daughter of the sky-god Anu. Another text talks about a demon shaped like a black dog that waited for merchant caravans. This demon might have been linked to the water-god Enki and represented thirst.

Images for kids

See also

- History of Mesopotamia

- List of Mesopotamian dynasties

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |