List of Assyrian kings facts for kids

Quick facts for kids King of Assyria |

|

|---|---|

| Iššiʾak Aššur šar māt Aššur |

|

Symbol of Ashur, the ancient Assyrian national deity

|

|

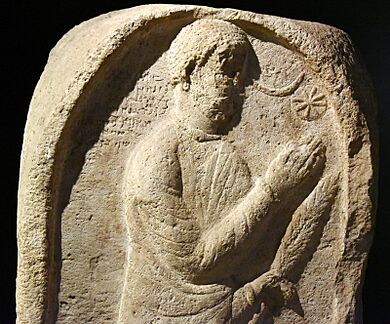

Relief depicting Ashurbanipal (r.669–631 BC) engaged in a lion hunt, a royal ritual meant to symbolically represent the Assyrian king's duty to bring order to the world

|

|

| Details | |

| First monarch | Tudiya (legendary) Puzur-Ashur I (independent city-state) Ashur-uballit I (first to use 'king') |

| Last monarch | Ashur-uballit II |

| Formation | 21st century BC |

| Abolition | 609 BC |

The king of Assyria was the ruler of the ancient kingdom of Assyria in Mesopotamia. This kingdom started in the late 21st century BC and ended in the late 7th century BC. For a long time, Assyria was just a small city-state centered around the city of Assur. But from the 14th century BC, powerful warrior kings helped Assyria grow. It became one of the biggest powers in the Ancient Near East. In its final centuries, it was the largest empire the world had ever seen.

Ancient Assyrian history is usually split into three main parts: the Old, Middle, and Neo-Assyrian periods. Each period had times when Assyria was strong and times when it declined.

The Assyrians did not believe their king was a god. Instead, they saw him as the special representative of their main god, Ashur. They believed Assyria was a place of order and peace. Lands not ruled by the Assyrian king (and by Ashur) were seen as chaotic. So, it was the king's job to expand Assyria's borders. This would bring order and civilization to lands they thought were wild.

As Assyria grew, its rulers took on grander titles. Early kings used the title Iššiʾak Aššur, meaning "representative of Ashur." They believed Ashur was the true king. From the time of Ashur-uballit I (14th century BC), rulers started using the title šar, meaning "king." Later, they added even bigger titles like "king of Sumer and Akkad" and "king of the Universe." These titles showed their control over all of Mesopotamia.

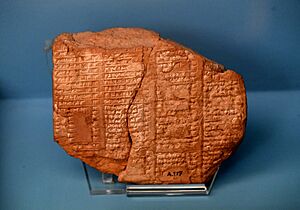

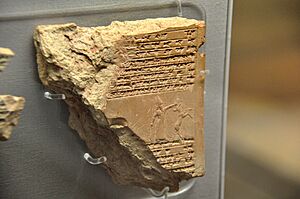

Most modern lists of Assyrian kings come from the Assyrian King List. This list was created and updated by the ancient Assyrians themselves over many centuries. Some parts of the list might be made up. However, it matches well with king lists from the Hittites, Babylonians, and ancient Egyptians. It also matches what archaeologists have found. So, it's generally considered a reliable record.

The line of Assyrian kings ended when Assyria's last king, Ashur-uballit II, was defeated. This happened in 609 BC by the Neo-Babylonian Empire and the Median Empire. After this, Assyria was no longer an independent country. However, the Assyrian people survived. They kept their culture and traditions, even becoming Christian later on.

Contents

Understanding the Kings of Assyria

How We Know About Them

Historians have found parts of king lists in three main ancient Assyrian cities: Assur, Dur-Sharrukin, and Nineveh. These lists are mostly the same. They were all copies of one original list. They were based on yearly appointments of officials called limmu. These officials were chosen by the king to lead the New Year festival. Because the lists are consistent, experts believe the years mentioned for each king are mostly correct.

There are some small differences in the lists, especially for kings before Ashur-dan I (around 1178 BC). After his time, the lists are identical. These king lists generally match records from other ancient kingdoms like the Hittites and Babylonians. They also match what archaeologists have discovered.

It's clear that some parts of the list might be fictional. Some known kings are not on the list, and some listed kings haven't been proven to exist independently. The oldest surviving list stops at Tiglath-Pileser II (967–935 BC). The newest list stops at Shalmaneser V (727–722 BC).

One challenge with the Assyrian King List is that it might have been created for political reasons. It might not always be perfectly accurate about dates. For example, during times of trouble, the list always shows a single line of kings. It probably ignored other people who tried to claim the throne. Also, there are some differences between the list and actual writings by Assyrian kings. These differences are often about family relationships. For instance, the list says Ashur-nirari II was the son of his predecessor, Enlil-Nasir II. But other writings show he was actually the son of Ashur-rabi I and brother of Enlil-Nasir.

Royal Titles and What They Meant

Assyrian royal titles often followed traditions from the Akkadian Empire (around 2334–2154 BC). This was an older civilization in Mesopotamia. When the central government of Ur collapsed, many new rulers didn't call themselves "king" (šar). Instead, they gave that title to their main gods. For Assyria, this god was Ashur. That's why most early Assyrian kings used the title Iššiʾak Aššur, meaning "governor of Assyria."

Unlike Babylonian kings, who focused on being protectors, Assyrian kings often used titles that showed their strength and power. Assyrian titles also often highlighted the king's family tree. They talked about the king's good qualities.

Assyrian royal titles could change depending on where they were displayed. A king might have different titles in Assyria than in conquered lands. Kings who controlled Babylon used a mix of Assyrian and Babylonian titles. This helped them show their control over Babylon. Titles like "chosen by the god Marduk" and "favourite of the god Ashur" showed they were legitimate rulers in both places.

Here's an example of a title from King Esarhaddon (681–669 BC), when Assyria ruled all of Mesopotamia:

The great king, the mighty king, king of the Universe, king of Assyria, viceroy of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, son of Sennacherib, the great king, the mighty king, king of Assyria, grandson of Sargon, the great king, the mighty king, king of Assyria; who under the protection of Assur, Sin, Shamash, Nabu, Marduk, Ishtar of Nineveh, Ishtar of Arbela, the great gods, his lords, made his way from the rising to the setting sun, having no rival.

The King's Important Role

Ancient Assyria was an absolute monarchy. This means the king had all the power. Assyrians believed their king was chosen directly by their chief god, Ashur. They thought the king was the link between the gods and the human world. So, the king's main job was to find out what the gods wanted and then make it happen. This often involved building temples or going to war. To help the king, there were priests at the royal court. They were trained to read signs from the gods.

The Assyrians believed their homeland was a perfect place of order. But lands ruled by other powers were seen as chaotic. The people in these "outer" lands were thought to be uncivilized. Because the king was connected to the gods, it was his duty to spread order throughout the world. He did this by conquering these chaotic countries. So, expanding the empire wasn't just about gaining land. It was also about bringing divine order and creating civilization.

Some ancient writings show that the god Ashur directly ordered kings to expand Assyria's borders. A text from King Tukulti-Ninurta I (around 1243–1207 BC) says the king was told to "broaden the land of Ashur." A similar writing from King Ashurbanipal (668–631 BC) commanded him to "extend the land at his feet."

The king also had to protect his own people. He was often called a "shepherd." This meant defending them from enemies and dangerous wild animals. For Assyrians, the most dangerous animal was the lion. Lions were seen as symbols of chaos. To prove they were strong protectors, Assyrian kings took part in special lion hunts. Only royalty could hunt lions. These hunts were public events, often held in parks near cities. Sometimes, they even used captive lions in an arena.

How Kings Gained Power

Unlike some other ancient kingdoms, like ancient Egypt, the Assyrian king was not thought to be a god himself. But he was believed to be chosen by the gods. Most kings showed their right to rule through their family connections to previous kings. They were legitimate because they were related to the great kings chosen by Ashur.

Sometimes, people who were not related to the previous kings took the throne. These were called usurpers. They usually either lied about being the son of a former king. Or, they claimed that Ashur had chosen them directly.

Two famous examples of such usurpers were Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC) and Sargon II (722–705 BC). Their writings don't mention family ties to past kings. Instead, they emphasized that Ashur himself had appointed them. They used phrases like "Ashur called my name" or "Ashur placed me on the throne."

Assyrian Kings Through History

Early Rulers and Dynasties

The Assyrian King List includes many rulers before the first kings we know for sure existed. Modern experts think some of these early names might be made up. This is because their names often rhyme, and they aren't found in other records. Also, some rulers known to have been in Assur before this time are missing from the list.

The earliest rulers are described as "kings who lived in tents." If they were real, they might have been nomadic tribal leaders, not kings of Assur itself. Like in the Sumerian King List, some names might have been rivals, not kings who ruled one after another. Some historians even think these names are just tribal names with no real link to Assyria.

Puzur-Ashur Dynasty (2025–1809 BC)

The dynasty started by Puzur-Ashur is called the 'Puzur-Ashur dynasty'. Puzur-Ashur I is generally seen as the founder of Assyria as an independent city-state around 2025 BC. These kings took power after the Neo-Sumerian Empire, which had ruled Assyria, collapsed.

| (Portrait) | Name | Reign | Succession and notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Assyrian period, 2025–1364 BC | ||||

| Puzur-Ashur I Puzur-Aššur |

Uncertain | Possibly first independent ruler of Assur | ||

| Shalim-ahum Šallim-aḫḫe |

Uncertain | Son of Puzur-Ashur I | ||

| Ilu-shuma Ilu-šūma |

Uncertain | Son of Shalim-ahum | ||

|

Erishum I Erišum |

c. 1974 – 1935 BC (40 years) |

Son of Ilu-shuma | |

| Ikunum Ikūnum |

c. 1934 – 1921 BC (14 years) |

Son of Erishum I | ||

|

Sargon I Šarru-kīn |

c. 1920 – 1881 BC (40 years) |

Son of Ikunum | |

| Puzur-Ashur II Puzur-Aššur |

c. 1880 – 1873 BC (8 years) |

Son of Sargon I | ||

|

Naram-Sin Narām-Sîn |

c. 1872 – 1829/1819 BC (54 or 44 years) |

Son of Puzur-Ashur II | |

| Erishum IIErišum | c. 1828/1818 – 1809 BC (20 or 10 years) |

Son of Naram-Sin | ||

Shamshi-Adad Dynasty (1808–1736 BC)

This dynasty was founded by Shamshi-Adad I. He took power from the Puzur-Ashur dynasty. Shamshi-Adad I and his family were from the south. They brought a new, more absolute style of kingship to Assyria, inspired by Babylon. Shamshi-Adad I was also the first Assyrian king to use the title 'king of the Universe'.

| (Portrait) | Name | Reign | Succession and notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shamshi-Adad I Šamši-Adad |

c. 1808 – 1776 BC (33 years) |

Usurper, not related to previous kings | |

| Ishme-Dagan I Išme-Dagān |

c. 1775 – 1765 BC (11 years) |

Son of Shamshi-Adad I | ||

| Mut-Ashkur Mut-Aškur |

Uncertain | Son of Ishme-Dagan I | ||

| Rimush Rimuš |

Uncertain | Uncertain relation | ||

| Asinum Asīnum |

Uncertain | Grandson (?) of Shamshi-Adad I | ||

Non-Dynastic Usurpers (1735–1701 BC)

These kings took the throne without being part of the main royal families.

| Name | Reign | Succession and notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Puzur-Sin Puzur-Sîn |

Uncertain | Usurper, not related to previous kings | |

| Ashur-dugul Aššur-dugul |

Uncertain (6 years) |

Usurper, not related to previous kings | |

| Ashur-apla-idi Aššur-apla-idi |

Uncertain | Usurper, not related to previous kings | |

| Nasir-Sin Nāṣir-Sîn |

Usurper, not related to previous kings | ||

| Sin-namir Sîn-nāmir |

Usurper, not related to previous kings | ||

| Ipqi-Ishtar Ipqi-Ištar |

Usurper, not related to previous kings | ||

| Adad-salulu Adad-ṣalulu |

Usurper, not related to previous kings | ||

| Adasi Adasi |

Usurper, not related to previous kings |

Adaside Dynasty (1700–722 BC)

This dynasty, started by Bel-bani, ruled Assyria for most of its history. It's also known as the Adasi dynasty. In Babylonia, it was called the "Baltil dynasty," after the oldest part of Assur city.

| (Portrait) | Name | Reign | Succession and notes | Ref | |

| Bel-bani Bēlu-bāni |

c. 1700 – 1691 BC (10 years) |

Son of Adasi | |||

| Libaya Libaia |

c. 1690 – 1674 BC (17 years) |

Son of Bel-bani | |||

| Sharma-Adad I Šarma-Adad |

c. 1673 – 1662 BC (12 years) |

Son of Libaya | |||

| Iptar-Sin Ibtar-Sîn |

c. 1661 – 1650 BC (12 years) |

Son of Sharma-Adad I | |||

| Bazaya Bāzā[y]a |

c. 1649 – 1622 BC (28 years) |

Son of Bel-bani | |||

| Lullaya Lulā[y]a |

c. 1621 – 1616 BC (6 years) |

Unrelated to other kings, possibly a usurper | |||

| Shu-Ninua Šu-Ninua |

c. 1615 – 1602 BC (14 years) |

Son of Bazaya | |||

| Sharma-Adad II Šarma-Adad |

c. 1601 – 1599 BC (3 years) |

Son of Shu-Ninua | |||

| Erishum III Erišum |

c. 1598 – 1586 BC (13 years) |

Son of Shu-Ninua | |||

| Shamshi-Adad II Šamši-Adad |

c. 1585 – 1580 BC (6 years) |

Son of Erishum III | |||

| Ishme-Dagan II Išme-Dagān |

c. 1579 – 1564 BC (16 years) |

Son of Shamshi-Adad II | |||

| Shamshi-Adad III Šamši-Adad |

c. 1563 – 1548 BC (16 years) |

Son of Shamshi-Adad II | |||

| Ashur-nirari I Aššur-nārāri |

c. 1547 – 1522 BC (26 years) |

Son of Ishme-Dagan II | |||

| Puzur-Ashur III Puzur-Aššur |

c. 1521 – 1498 BC (24 years) |

Son of Ashur-nirari I | |||

| Enlil-nasir I Enlīl-nāsir |

c. 1497 – 1485 BC (13 years) |

Son of Puzur-Ashur III | |||

| Nur-ili Nur-ili |

c. 1484 – 1473 BC (12 years) |

Son of Enlil-nasir I | |||

| Ashur-shaduni Aššur-šaddûni |

c. 1473 BC (1 month) |

Son of Nur-ili | |||

| Ashur-rabi I Aššur-rabi |

c. 1472 – 1453 BC (20 years) |

Son of Enlil-nasir I, took the throne from his nephew | |||

| Ashur-nadin-ahhe I Aššur-nādin-ahhē |

c. 1452 – 1431 BC (22 years) |

Son of Ashur-rabi I | |||

| Enlil-nasir II Enlīl-nāsir |

c. 1430 – 1425 BC (6 years) |

Son of Ashur-rabi I, took the throne from his brother | |||

| Ashur-nirari II Aššur-nārāri |

c. 1424 – 1418 BC (7 years) |

Son of Ashur-rabi I | |||

| Ashur-bel-nisheshu Aššūr-bēl-nīšēšu |

c. 1417 – 1409 BC (9 years) |

Son of Ashur-nirari II | |||

| Ashur-rim-nisheshu Aššūr-rem-nīšēšu |

c. 1408 – 1401 BC (8 years) |

Son of Ashur-nirari II | |||

| Ashur-nadin-ahhe II Aššur-nādin-ahhē |

c. 1400 – 1391 BC (10 years) |

Son of Ashur-rim-nisheshu | |||

| Eriba-Adad I Erība-Adad |

c. 1390 – 1364 BC (27 years) |

Son of Ashur-bel-nisheshu | |||

| Middle Assyrian Empire, 1363–912 BC | |||||

| Ashur-uballit I Aššur-uballiṭ |

c. 1363 – 1328 BC (36 years) |

Son of Eriba-Adad I, first to use the title šar māt Aššur (king of Assyria) | |||

| Enlil-nirari Enlīl-nārāri |

c. 1327 – 1318 BC (10 years) |

Son of Ashur-uballit I | |||

| Arik-den-ili Arīk-den-ili |

c. 1317 – 1306 BC (12 years) |

Son of Enlil-nirari | |||

| Adad-nirari I Adad-nārārī |

c. 1305 – 1274 BC (32 years) |

Son of Arik-den-ili | |||

| Shalmaneser I Salmānu-ašarēd |

c. 1273 – 1244 BC (30 years) |

Son of Adad-nirari I | |||

|

Tukulti-Ninurta I Tukultī-Ninurta |

c. 1243 – 1207 BC (37 years) |

Son of Shalmaneser I | ||

| Ashur-nadin-apli Aššūr-nādin-apli |

c. 1206 – 1203 BC (4 years) |

Son of Tukulti-Ninurta I, took the throne from his father | |||

| Ashur-nirari III Aššur-nārāri |

c. 1202 – 1197 BC (6 years) |

Son of Ashur-nadin-apli | |||

| Enlil-kudurri-usur Enlīl-kudurri-uṣur |

c. 1196 – 1192 BC (5 years) |

Son of Tukulti-Ninurta I | |||

| Ninurta-apal-Ekur Ninurta-apal-Ekur |

c. 1191 – 1179 BC (13 years) |

Great-great-great-grandson of Adad-nirari I, took the throne from his distant cousin | |||

| Ashur-dan I Aššur-dān |

c. 1178 – 1133 BC (46 years) |

Son of Ninurta-apal-Ekur | |||

| Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur Ninurta-tukultī-Aššur |

c. 1132 BC (less than a year) |

Son of Ashur-dan I | |||

| Mutakkil-Nusku Mutakkil-Nusku |

c. 1132 BC (less than a year) |

Son of Ashur-dan I, took the throne from his brother | |||

| Ashur-resh-ishi I Aššur-rēša-iši |

1132 – 1115 BC (18 years) |

Son of Mutakkil-nusku | |||

|

Tiglath-Pileser I Tukultī-apil-Ešarra |

1114 – 1076 BC (39 years) |

Son of Ashur-resh-ishi I | ||

| Asharid-apal-Ekur Ašarēd-apil-Ekur |

1075 – 1074 BC (2 years) |

Son of Tiglath-Pileser I | |||

| Ashur-bel-kala Aššūr-bēl-kala |

1073 – 1056 BC (18 years) |

Son of Tiglath-Pileser I; a century-long period of decline followed Ashur-bel-kala's death | |||

| Eriba-Adad II Erība-Adad |

1055 – 1054 BC (2 years) |

Son of Ashur-bel-kala | |||

| Shamshi-Adad IV Šamši-Adad |

1053 – 1050 BC (4 years) |

Son of Tiglath-Pileser I, took the throne from his nephew | |||

| Ashurnasirpal I Aššur-nāṣir-apli |

1049 – 1031 BC (19 years) |

Son of Shamshi-Adad IV | |||

| Shalmaneser II Salmānu-ašarēd |

1030 – 1019 BC (12 years) |

Son of Ashurnasirpal I | |||

| Ashur-nirari IV Aššur-nārāri |

1018 – 1013 BC (6 years) |

Son of Shalmaneser II | |||

| Ashur-rabi II Aššur-rabi |

1012 – 972 BC (41 years) |

Son of Ashurnasirpal I | |||

| Ashur-resh-ishi II Aššur-rēša-iši |

971 – 967 BC (5 years) |

Son of Ashur-rabi II | |||

| Tiglath-Pileser II Tukultī-apil-Ešarra |

966 – 935 BC (32 years) |

Son of Ashur-resh-ishi II | |||

| Ashur-dan II Aššur-dān |

934 – 912 BC (23 years) |

Son of Tiglath-Pileser II, began to reconquer lost territory | |||

| Neo-Assyrian Empire, 911–609 BC | |||||

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details and notes | Ref |

| Adad-nirari II Adad-nārārī |

911 – 891 BC (21 years) |

Son of Ashur-dan II | |||

| Tukulti-Ninurta II Tukultī-Ninurta |

890 – 884 BC (7 years) |

Son of Adad-nirari II | |||

|

Ashurnasirpal II Aššur-nāṣir-apli |

884 – 859 BC (25 years) |

Son of Tukulti-Ninurta II | Changed the Assyrian capital to Nimrud. Campaigned to the Mediterranean. First Assyrian king to make extensive use of reliefs. Died a natural death. | |

|

Shalmaneser III Salmānu-ašarēd |

859 – 824 BC (35 years) |

Son of Ashurnasirpal II | Fully restored Assyia's ancient borders. Died a natural death. | |

|

Shamshi-Adad V Šamši-Adad |

824 – 811 BC (13 years) |

Son of Shalmaneser III, defeated his brother Ashur-danin-pal in a civil war | Conquered Babylon, but it became independent again later. Died relatively young. | |

|

Adad-nirari III Adad-nārārī |

811 – 783 BC (28 years) |

Son of Shamshi-Adad V. His mother Shammuramat may have ruled with him when he was young. | His later reign is less known. Assyrian officials gained much power. Probably died of natural causes. | |

| Shalmaneser IV Salmānu-ašarēd |

783 – 773 BC (10 years) |

Son of Adad-nirari III | His fate is unclear due to missing records. | ||

| Ashur-dan III Aššur-dān |

773 – 755 BC (18 years) |

Son of Adad-nirari III | His fate is unclear due to missing records. | ||

| Ashur-nirari V Aššur-nārāri |

755 – 745 BC (10 years) |

Son of Adad-nirari III | His fate is unclear, possibly removed from power by Tiglath-Pileser III. | ||

|

Tiglath-Pileser III Tukultī-apil-Ešarra |

745 – 727 BC (18 years) |

Son of either Adad-nirari III or Ashur-nirari V. Took the throne in unclear circumstances. | Made the Assyrian Empire very powerful in the Near East. Conquered Babylon. Died a natural death. | |

|

Shalmaneser V Salmānu-ašarēd |

727 – 722 BC (5 years) |

Son of Tiglath-Pileser III | Removed from power and killed by Sargon II in a palace coup. | |

Sargonid Dynasty (722–609 BC)

This was the last major dynasty of Assyrian kings.

| Portrait | Name | Reign | Succession | Life details and notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sargon II Šarru-kīn |

722 – 705 BC (17 years) |

Claimed to be son of Tiglath-Pileser III. Took the throne from Shalmaneser V. | Changed the Assyrian capital to Dur-Sharrukin. Killed in battle in Anatolia. | |

|

Sennacherib Sîn-aḥḥē-erība |

705 – 681 BC (24 years) |

Son of Sargon II | Changed the Assyrian capital to Nineveh. Murdered by his eldest son. | |

|

Esarhaddon Aššur-aḫa-iddina |

681 – 669 BC (12 years) |

Son of Sennacherib. Fought a civil war against his brother to become king. | Expanded Assyria to its largest size ever. Was often sick. Died of natural causes while going to fight in Egypt. | |

|

Ashurbanipal Aššur-bāni-apli |

669 – 631 BC (38 years) |

Son of Esarhaddon. His brother ruled Babylonia, but Ashurbanipal took full control after a civil war. | Considered the last great Assyrian king. His fate is unclear, probably died a natural death. | |

| Aššur-etil-ilāni Aššur-etil-ilāni |

631 – 627 BC (4 years) |

Son of Ashurbanipal | His fate is unclear due to missing records. | ||

|

Sîn-šumu-līšir Sîn-šumu-līšir (usurper) |

626 BC (3 months) |

A powerful general. Rebelled when Sîn-šar-iškun became king. Ruled only northern Babylonia. | The only eunuch to claim the Assyrian throne. Defeated by Sîn-šar-iškun. | |

| Sîn-šar-iškun Sîn-šar-iškun |

627 – 612 BC (15 years) |

Son of Ashurbanipal, became king after Aššur-etil-ilāni's death | Killed by the forces of the Babylonians and Medes when Nineveh fell. | ||

| Aššur-uballiṭ II Aššur-uballiṭ |

612 – 609 BC (3 years) |

Possibly son of Sîn-šar-iškun. Led resistance against the Medes and Babylonians at Harran. | Defeated by the Babylonians at the Siege of Harran. His fate after that is unknown. | ||

Assyria After the Empire

A New Chapter for Assyria

The defeat of Ashur-uballit II in 609 BC marked the end of the ancient Assyrian monarchy. It was never brought back. The Assyrian Empire's land was divided between the Neo-Babylonian and Median empires. The Assyrian people survived, but Assyria became a less important region.

However, under the Seleucid and Parthian empires, Assyria saw a remarkable recovery. In the last two centuries of Parthian rule, many new settlements appeared. The region became as populated as it was during the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

A semi-independent city-state formed around Assur, Assyria's oldest capital. This happened around the end of the 2nd century BC. The ancient city thrived. Old buildings were restored, and new ones, like a palace, were built. The ancient temple dedicated to the god Ashur was also restored in the 2nd century AD. They even used a religious calendar almost identical to the one from the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Stelae (stone slabs with carvings) made by the local rulers of Assur during this time looked like those made by the old Assyrian kings. These rulers used the title maryo of Assur, meaning "master of Assur." They seemed to see themselves as continuing the old Assyrian royal tradition. This period of Assyrian cultural growth in Assur ended around 240 AD. This was when the Sasanian Empire conquered the region. The Ashur temple was destroyed again, and the city's people were scattered.

City-Lords of Assur

We don't know much about the local rulers of Assur during the centuries of Parthian rule. Only five names are known. Their exact dates and order are unclear.

| Name | Timespan | Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormoz Hormoz (or Hormez?) |

Uncertain | Iranian name. Known from an inscription on a statue. | |

| Hayyay Rāʾeḥat Hayyay |

Uncertain | Arabic name. Mentioned in an inscription. | |

| Hanni Ḥannī |

Uncertain | Akkadian-derived Aramaic name. Mentioned as the father of a person (whose name is illegible) in a relief. | |

| Rʻuth-Assor Rʿūṯʾassor |

2nd century AD | Akkadian-derived Aramaic name. Mentioned in inscriptions and in his own stele. | |

| [unknown name] | 2nd century AD | Indirectly mentioned in an inscription by his nephews, but his name is not saved. | |

| Nbudayyan Nḇūḏayyān |

2nd century AD | Akkadian-derived Aramaic name. Mentioned in multiple inscriptions. |

See also

- List of kings of Babylon – for the Babylonian kings

- List of Mesopotamian dynasties – for other dynasties and kingdoms in ancient Mesopotamia

- List of kings of Syria – the Seleucids who became kings of Syria

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |