Šamaš-šuma-ukin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Šamaš-šuma-ukin |

|

|---|---|

|

|

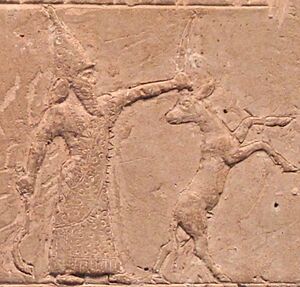

Šamaš-šuma-ukin, as king of Babylon, depicted on a tablet recording his confirmation of a grant

|

|

| King of Babylon | |

| Reign | 668–648 BC |

| Predecessor | Esarhaddon |

| Successor | Kandalanu |

| Born | before 685 BC |

| Died | 648 BC |

| Akkadian | Šamaš-šuma-ukin Šamaš-šumu-ukīn |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Esarhaddon |

| Mother | Ešarra-ḫammat |

Šamaš-šuma-ukin was a powerful ruler who became king of Babylon in 668 BC. He was part of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, but he ruled Babylon as a dependent king. He was the son of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon and the older brother of Ashurbanipal, who became the next Assyrian king.

Even though Šamaš-šuma-ukin was the older son, he wasn't chosen to be the king of Assyria. Instead, his father, Esarhaddon, made him king of Babylon. This was probably to stop fights between the brothers. Esarhaddon wanted them to be "equal brothers." However, Ashurbanipal didn't follow these plans. Šamaš-šuma-ukin became king of Babylon a few months after Ashurbanipal became king of Assyria. He was always watched closely and couldn't make big decisions without Ashurbanipal's approval.

Šamaš-šuma-ukin, even though he was Assyrian, really embraced Babylonian culture. His writings as king sounded very Babylonian. He took part in the Babylonian New Year's festival and other local traditions. A very important statue of Marduk, Babylon's main god, was returned to the city when Šamaš-šuma-ukin became king. This statue had been stolen by his grandfather, Sennacherib, 20 years earlier.

For many years, Šamaš-šuma-ukin and Ashurbanipal got along. But Šamaš-šuma-ukin grew tired of Ashurbanipal's control. In 652 BC, Šamaš-šuma-ukin started a rebellion. He convinced the Babylonians to join him. He also got other enemies of Assyria to help, like the Elamites, Chaldeans, and Arameans. The war was tough at first, but it ended badly for Šamaš-šuma-ukin. Ashurbanipal captured Babylon in 648 BC after a long siege. Šamaš-šuma-ukin died, but exactly how he died is not clear. After his death, people tried to erase his memory by damaging his images.

Contents

Becoming King of Babylon

Šamaš-šuma-ukin was likely the second oldest son of Esarhaddon, who was the third king of the Sargonid dynasty. His older brother, Sin-nadin-apli, died unexpectedly in 674 BC. This caused problems for Esarhaddon, who wanted to avoid a fight over who would be king after him.

Esarhaddon decided that his fourth son, Ashurbanipal, would become king of Assyria. Šamaš-šuma-ukin, the next oldest son, was chosen to rule Babylonia. Esarhaddon called them "equal brothers." But he also made it clear that Šamaš-šuma-ukin had to promise loyalty to Ashurbanipal.

This idea of having two kings, one for Assyria and one for Babylonia, was new. For many years, the Assyrian king ruled both. It's not fully clear why Esarhaddon chose a younger son (Ashurbanipal) for the main Assyrian throne. Some historians think it might be because Ashurbanipal and Šamaš-šuma-ukin had different mothers. Perhaps Šamaš-šuma-ukin's mother was Babylonian, which would make him a better fit for the Babylonian throne.

As a prince, Šamaš-šuma-ukin learned important royal skills. These included hunting, riding, and military training. Because their father Esarhaddon was often sick, both Ashurbanipal and Šamaš-šuma-ukin helped with running the empire. This gave them real experience in leadership.

Ashurbanipal became king of Assyria right after Esarhaddon died. Šamaš-šuma-ukin was crowned king of Babylon a few months later. A very important part of his crowning was the return of the Statue of Marduk to Babylon. This statue had been stolen by Šamaš-šuma-ukin's grandfather, Sennacherib, 20 years before. For Babylonians, the return of the statue meant that their god Marduk approved of the new king.

Šamaš-šuma-ukin ruled Babylon for 16 years. He generally had peaceful relations with his younger brother. However, they often disagreed about how much power Šamaš-šuma-ukin actually had. Esarhaddon had said Ashurbanipal shouldn't interfere in Šamaš-šuma-ukin's affairs. But Ashurbanipal didn't follow this. He might have been afraid that his older brother would become too powerful and threaten his rule.

Šamaš-šuma-ukin's Rule

Early Years and Power

Šamaš-šuma-ukin was the only Assyrian prince who became king of Babylon without also becoming king of Assyria. Being king of Babylon was very important to the Assyrians for many reasons, so it was a respected position. However, Šamaš-šuma-ukin was clearly a dependent ruler, not fully independent.

Esarhaddon's writings suggest Šamaš-šuma-ukin should have ruled all of Babylonia. But records from that time only show him ruling Babylon itself and the areas nearby. Governors of other Babylonian cities, like Nippur and Uruk, still saw Ashurbanipal as their king. Šamaš-šuma-ukin also didn't have a large army. When the Elamite king Teumman attacked Babylonia in 653 BC, Šamaš-šuma-ukin couldn't defend his land alone. He had to ask Ashurbanipal for military help.

Šamaš-šuma-ukin took part in many traditional Babylonian royal activities. He rebuilt the walls of the city Sippar. He also participated in the Babylonian New Year's festival, which had stopped when the Marduk statue was gone. He paid a lot of attention to the temples in his kingdom. He confirmed offerings and even increased the land for the Ishtar temple in Uruk.

Even though he was Assyrian, Šamaš-šuma-ukin seemed to fit in well with Babylonian culture. His royal writings used a lot of Babylonian ideas and language. He was likely the first king of his family to live in Babylon full-time. Throughout his rule, Šamaš-šuma-ukin started many building projects. This was a key part of being a Babylonian king, just like military campaigns were important for Assyrian kings. He restored shrines and rebuilt city walls.

Ashurbanipal often said in his writings that he was the one who gave Šamaš-šuma-ukin power over Babylon. This might be because Šamaš-šuma-ukin was crowned a few months after Ashurbanipal became king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal could have stopped the crowning if he wanted to.

Growing Problems

We don't know the exact reasons why Šamaš-šuma-ukin rebelled against Ashurbanipal. But there are a few ideas. The most common one is that Ashurbanipal didn't respect Esarhaddon's plan for Šamaš-šuma-ukin to rule all of Babylonia.

Even though Šamaš-šuma-ukin's documents are found across Babylonia, showing he was seen as king, Ashurbanipal also had documents from Babylonia. This suggests Ashurbanipal was acting like a Babylonian king too, even though there already was one.

Cities like Babylon and Sippar seemed to be firmly under Šamaš-šuma-ukin's control. But Ashurbanipal had his own people and spies all over the south. Any orders Šamaš-šuma-ukin gave had to be checked and approved by Ashurbanipal first. Ashurbanipal even had soldiers and officials living in Borsippa, a city deep inside Šamaš-šuma-ukin's territory. People in Babylon would also send letters directly to Ashurbanipal, not to Šamaš-šuma-ukin. This shows who they thought was truly in charge.

Royal records from Babylonia mentioned both kings' names when they were getting along. But Assyrian documents only mentioned Ashurbanipal. This shows they weren't seen as equals. A governor from Uruk called Ashurbanipal "king of the Lands," even though Uruk was in Babylonia. This means he saw Ashurbanipal as his true ruler.

Šamaš-šuma-ukin himself seemed to think he was equal to Ashurbanipal. He called him "my brother" in letters, unlike how he addressed his father, "the king, my father." We have many letters from Šamaš-šuma-ukin to Ashurbanipal, but no replies from Ashurbanipal. Maybe Ashurbanipal didn't feel the need to write back because he had so many spies.

By the 650s BC, their relationship was much worse. A letter from a court official said that visitors had criticized Ashurbanipal in front of Šamaš-šuma-ukin. The official reported that Šamaš-šuma-ukin was angry but chose not to act. The main reasons for Šamaš-šuma-ukin's rebellion were likely his unhappiness with his position, the Babylonians' dislike of Assyrian rule, and the Elamite king's willingness to fight Assyria.

The Great Revolt and Fall

In 652 BC, Šamaš-šuma-ukin rebelled. He wanted Babylon to be free from Ashurbanipal's control. Old stories say that their sister, Šērūʾa-ēṭirat, tried to stop them from fighting. When the war started, she supposedly went into exile. The war between the brothers lasted for three years. Šamaš-šuma-ukin wasn't trying to become king of Assyria. He just wanted Babylon to be independent.

Šamaš-šuma-ukin asked the people of Babylon to join his revolt. Ashurbanipal's writings quote his brother saying, "Ashurbanipal will shame the name of the Babylonians." Ashurbanipal called these words "lies." Soon after Šamaš-šuma-ukin started his revolt, other parts of southern Mesopotamia also rose up against Ashurbanipal.

Ashurbanipal tried to get local governors to join his side. In his letters, he never called Šamaš-šuma-ukin by name. He called him "no-brother," "unfaithful brother," or just "the enemy." He even called him "this man whom Marduk hates" to make him seem less legitimate as a Babylonian king.

Ashurbanipal's records say that Šamaš-šuma-ukin was very good at finding allies. He got help from the Chaldeans, Arameans, and other people in Babylonia. The Elamites also sent an army to help. Some kings from distant lands might have also joined, possibly the Medes.

For the first two years, battles happened all over Babylonia. Both sides won some fights. The war became very confusing, with many smaller groups changing sides. One famous double agent was Nabu-bel-shumati, a governor who kept switching his loyalty, making Ashurbanipal very angry.

Siege of Babylon and Death

Even with many allies, Šamaš-šuma-ukin's revolt failed. His allies and lands were slowly lost. The Elamites, his main helpers, were defeated and left the war. By 650 BC, things looked bad for Šamaš-šuma-ukin. Ashurbanipal's forces surrounded Sippar, Borsippa, Kutha, and Babylon itself.

During the siege of Babylon, the city suffered from a severe lack of food. After two years, Babylon finally fell in 648 BC. The Assyrian army took many valuable things from the city.

When Babylon fell, a huge fire spread through the city. Šamaš-šuma-ukin's exact fate is not fully clear. Many historians believe he died by setting himself on fire in his palace. However, old texts only say he "met a cruel death" and that the gods "consigned him to a fire." It's possible he was executed, died by accident, or was killed in another way. Most stories say fire was involved, but they don't give many details. The texts often say the gods were involved because Ashurbanipal saw his brother's war as disrespectful to the gods.

If Šamaš-šuma-ukin was executed, the Assyrian writers might have left that out. Killing a brother was against the law, even if a soldier did it. After Šamaš-šuma-ukin's death, Ashurbanipal put one of his own officials, Kandalanu, on the Babylonian throne as a dependent ruler.

What Happened After

Šamaš-šuma-ukin's rebellion and defeat were a difficult topic for the Assyrian writers who recorded history. He was part of the Assyrian royal family but also a rebellious king of Babylon. It was hard to write about his end. While scribes eagerly wrote about defeating foreign kings, they were hesitant to write about the death of their own royal family members. It was also complicated because Šamaš-šuma-ukin wasn't just a rebel; he was the rightful ruler of Babylon, chosen by an Assyrian king.

Ashurbanipal's own writings don't say much about how Šamaš-šuma-ukin died. Later Assyrian kings don't mention him at all, almost as if he never existed. Ashurbanipal's writings often avoid saying his brother's name, just calling him "the king." In a carving from Ashurbanipal's palace, soldiers are shown giving him the Babylonian crown. But Šamaš-šuma-ukin is clearly missing. There's evidence that people tried to erase his memory after his defeat. Statues he put up were damaged, and his face was removed.

Royal Titles

Šamaš-šuma-ukin's most common title was šar Bābili ("king of Babylon"). He also used other traditional Babylonian royal titles, like šar māt Šumeri u Akkadi ("king of Sumer and Akkad"). His titles were much more Babylonian than those of other Assyrian rulers of the city.

Like other Assyrian kings, Šamaš-šuma-ukin honored his ancestors in his writings. He usually named his great-grandfather Sargon II, his grandfather Sennacherib, and his father Esarhaddon. Sometimes he even included his brother Ashurbanipal. He might have done this because he worried people would question his right to rule if he didn't mention them. The way he presented his ancestors and used gods in his titles made him different from other Assyrian rulers.

Importantly, Šamaš-šuma-ukin didn't mention his ancestors' role as chief priests of Assyria's god Ashur. This was a key part of Assyrian kingship. As a ruler of Babylon, he most often mentioned Marduk, the main god of Babylon. His writings never mentioned Ashur, even though other Assyrian kings who ruled both Assyria and Babylonia included Ashur in their titles. This suggests that Šamaš-šuma-ukin, despite being Assyrian, didn't worship Assyria's national god. In many of his titles, he used Assyrian ways of mentioning gods but replaced Assyrian gods like Ashur with gods more important in the south, like Marduk.

See also

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |