Mari, Syria facts for kids

|

تل حريري

|

|

Ruins of Mari

|

|

| Alternative name | Tell Hariri |

|---|---|

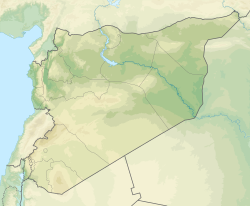

| Location | Abu Kamal, Deir ez-Zor Governorate, Syria |

| Coordinates | 34°32′58″N 40°53′24″E / 34.54944°N 40.89000°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 60 hectares (150 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 2900 BC |

| Abandoned | 3rd century BC |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

| Cultures | East-Semitic (Kish civilization), Amorite |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | André Parrot |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

Mari was an ancient city in what is now Syria. It was a powerful "city-state," meaning it was a city that also acted like an independent country. Today, its remains are found in a large mound called a tell, about 11 kilometers (7 miles) northwest of Abu Kamal.

Mari was a very important place for trade and power between 2900 BC and 1759 BC. It was built right in the middle of the Euphrates River trade routes. These routes connected Sumer (in the south) with the Eblaite kingdom and the Levant (in the west).

The city was first left empty around 2550 BC. But it was soon rebuilt and became the capital of a strong kingdom. This second Mari was known for its close ties to Sumerian culture. It fought a long war with its rival, Ebla. In the 23rd century BC, Mari was destroyed by the Akkadians. However, they allowed the city to be rebuilt and put a military governor in charge.

These governors later became independent rulers. They rebuilt Mari into a major center in the Euphrates valley. Their rule lasted until the late 19th century BC. After that, Mari became the capital of the Amorite Lim dynasty. This Amorite kingdom didn't last long. It was destroyed by Babylonia around 1761 BC. Mari continued as a small settlement under Babylonian and Assyrian rule. Eventually, it was abandoned and forgotten during the Hellenistic period (around 3rd century BC).

The people of Mari, called Mariotes, worshipped both Semitic and Sumerian gods. The city was a huge trading hub. Even though Sumerian culture had a big impact, Mari was a Semitic-speaking nation. Its language was similar to Eblaite. The Amorites, who were West Semites, became the main group in the area by the time of the Lim dynasty (around 1830 BC).

Mari was discovered in 1933. This discovery gave us amazing information about ancient Mesopotamia and Syria. Over 25,000 clay tablets were found. These tablets explain how the government worked and how different kingdoms dealt with each other. They also showed how wide the trade networks were in the 18th century BC. Trade connected Mari to places as far as Afghanistan and Crete.

Contents

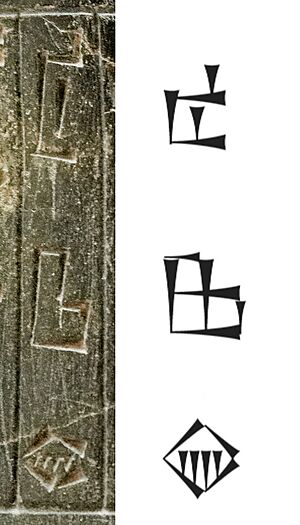

The Name of Mari

The name of the city, written in Cuneiform as ma-riki, comes from Itūr-Mēr. He was an ancient storm god from northern Mesopotamia and Syria. This god was seen as the special protector of the city. Because the city's name was spelled just like the storm god's, it's believed Mari was named after him.

History of Mari

Early Times

The First Kingdom

Mari was founded around 2900 BC. It wasn't a small village that grew big. Instead, it was built as a new city to control trade routes on the Euphrates River. These routes connected the Levant with southern Sumer.

The city was built about 1 to 2 kilometers (0.6 to 1.2 miles) away from the Euphrates River. This protected it from floods. An artificial canal, 7 to 10 kilometers (4 to 6 miles) long, connected the city to the river.

It's hard to dig up this early city because it's buried deep under later layers. But archaeologists found a circular wall that protected the city from floods. Inside this wall was an area for gardens and workshops. There was also a strong inner wall, 6.7 meters (22 feet) thick and 8 to 10 meters (26 to 33 feet) high, with defensive towers.

Other discoveries include one of the city gates and a street that led from the center to the gate. Mari had a central mound, but no temple or palace has been found there yet. A large building, possibly for government use, was also found. The city was abandoned around 2550 BC for reasons we don't know.

The Second Kingdom

Mari was rebuilt and settled again before 2500 BC. The new city kept many features of the first one, like the inner wall and gate. The outer circular wall, 1.9 kilometers (1.2 miles) wide, was also kept. It was topped with a two-meter-thick wall to protect archers.

However, the inside of the city was completely changed and carefully planned. Streets were built to drain rainwater from the higher center down to the gates.

A royal palace was built in the heart of the city. It also served as a temple. Archaeologists found four different building levels of this palace from the second kingdom. The last two levels are from the Akkadian Empire period. The first two levels showed a temple dedicated to an unknown god, a throne room, and a hall leading to the temple.

Six smaller temples were found in the city. These included temples dedicated to Ishtar, Ninhursag, and Shamash. Most temples were in the city center. The area between the main temple and another temple (Massif Rouge) was likely the administrative center for the high priest.

The second kingdom was a powerful and rich political center. Its kings used the title Lugal, which means "king." We know about many of them from a letter written by King Enna-Dagan around 2350 BC. This letter was sent to Irkab-Damu of Ebla. In it, the Mariote king talks about his ancestors and their military victories.

Mari's War with Ebla

The earliest king mentioned in Enna-Dagan's letter is Ansud. He attacked Ebla, Mari's main rival, and conquered many of Ebla's cities. The war continued with other kings. King Igrish-Halam of Ebla had to pay tribute to Iblul-Il of Mari. Iblul-Il conquered many Eblaite cities.

The war reached its peak when Ebla's vizier (a high official) Ibbi-Sipish formed an alliance. He teamed up with Nagar and Kish to defeat Mari in a battle near Terqa. Ebla itself was destroyed a few years later, around 2300 BC, during the reign of Mariote king Hidar. Some historians believe that Ishqi-Mari, Hidar's successor, was responsible for Ebla's destruction.

Mari's Destruction by Sargon of Akkad

Just ten years after Ebla's destruction, Mari was also destroyed and burned by Sargon of Akkad. This is known from one of Sargon's year names, which says, "Year in which Mari was destroyed." This likely happened around 2265 BC. Ishqi-Mari was probably the last king of Mari before Sargon's conquests. Sargon of Akkad collected tribute from Mari and Elam.

Later Kingdoms

The Third Kingdom and Shakkanakku Rulers

Mari was empty for about two generations. Then, the Akkadian king Manishtushu rebuilt it. He appointed a governor to rule the city, who was called a Shakkanakku (military governor). Akkad kept direct control over Mari. For example, Naram-Sin of Akkad appointed two of his daughters to religious roles in the city.

The first Shakkanakku listed was Ididish, appointed around 2266 BC. He ruled for 60 years, and his son took over after him, making the position hereditary.

The third Mari kept the general layout of the second city. The old royal palace was replaced with a new one for the Shakkanakku. Another smaller palace was built in the eastern part of the city. The city walls were rebuilt and made stronger. The old sacred area was kept, as was the temple of Ninhursag. A new temple, called the "temple of lions" (dedicated to Dagan), was built by the Shakkanakku Ishtup-Ilum.

Akkad's power weakened, and Mari became independent. But the rulers still used the title Shakkanakku. Mari was technically under the rule of Ur for a while. However, this didn't stop Mari from being independent. Some Shakkanakkus even used the royal title Lugal in their inscriptions. This dynasty ended for unknown reasons before the next one began in the late 19th century BC.

The Lim Dynasty

In the second millennium BC, the Amorites expanded across the Fertile Crescent. Around 1830 BC, Mari became the capital of the Amorite Lim dynasty under King Yaggid-Lim. However, there was a lot of continuity between the Shakkanakku and Amorite periods.

Yaggid-Lim was a ruler before he took control of Mari. He made an alliance with Ila-kabkabu of Ekallatum, but they later went to war. Yaggid-Lim was killed by his servants. His son, Yahdun-Lim, became king of Mari around 1820 BC.

Yahdun-Lim started his rule by putting down rebellions. He rebuilt the walls of Mari and Terqa. He also built a new fort. He expanded his kingdom west, possibly reaching the Mediterranean Sea. However, he faced a rebellion from nomads. These rebels were supported by Yamhad's king Sumu-Epuh. Yahdun-Lim defeated the rebels. He then faced a rivalry with Shamshi-Adad I of Shubat-Enlil. Mari lost this war, and Yahdun-Lim was killed around 1798 BC. His possible son, Sumu-Yamam, took the throne but was also killed two years later. Shamshi-Adad then took over Mari.

Assyrian Rule and Zimri-Lim

Shamshi-Adad (ruled 1809-1775 BC) put his son Yasmah-Adad on the throne of Mari. Yasmah-Adad married Yahdun-Lim's daughter. The rest of the Lim family fled to Yamhad. Shamshi-Adad tried to strengthen his position against Yamhad. He had Yasmah-Adad marry the daughter of the king of Qatna. But Yasmah-Adad was not a good leader. His father was angry with him.

When Shamshi-Adad died around 1776 BC, the armies of Yarim-Lim I of Yamhad advanced. They supported Zimri-Lim, the heir of the Lim dynasty.

Zimri-Lim took the throne around 1776 BC. He married Princess Shibtu, the daughter of Yarim-Lim I. Zimri-Lim's rise to power, with Yamhad's help, changed Mari's status. Zimri-Lim called Yarim-Lim his "father." The Yamhadite king could even give orders to Mari.

Zimri-Lim began his rule with a campaign against nomads. He also made alliances with Eshnunna and Hammurabi of Babylon. He sent his armies to help the Babylonians. He expanded his kingdom north into the Upper Khabur region. There, he made local kingdoms his vassals. Mari prospered as a trading center and had a time of peace. Zimri-Lim's greatest achievement was renovating the Royal Palace. It was greatly expanded to have 275 rooms. It held beautiful artifacts like "The Goddess of the Vase" statue. It also had a royal archive with thousands of clay tablets.

Babylonian Period

Relations with Babylon worsened over a dispute about the city of Hīt. A war against Elam involved both kingdoms around 1765 BC. Finally, Hammurabi invaded Mari. He defeated Zimri-Lim in battle around 1761 BC, ending the Lim dynasty. Terqa became the capital of a smaller state called the Kingdom of Khana.

Mari survived the destruction. It rebelled against Babylon around 1759 BC. This caused Hammurabi to destroy the entire city. However, Mari might have survived as a small village under Babylonian rule.

Later History

Later, Mari became part of Assyria. It was listed among the lands conquered by the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I (ruled 1243–1207 BC). After that, Mari was often fought over by Assyria and Babylon.

In the middle of the 11th century BC, Mari became part of Hana. Its king, Tukulti-Mer, called himself "king of Mari." He rebelled against Assyria. Mari later came under the firm control of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Around 760 BC, Shamash-Risha-Usur was an independent governor. He ruled parts of the middle Euphrates. He called himself the governor of Suhu and Mari. However, by that time, Mari was likely in a different area. So, he might have used the title for historical reasons.

Mari continued as a small settlement until the Hellenistic period. Then, it disappeared from records.

Modern History

By 2015, ISIS damaged and looted the site of Mari. The royal palace was especially targeted. It was one of the first archaeological sites taken over by this group.

People, Language, and Government

The first people to found Mari might have been Sumerians. But it's more likely they were East Semitic-speaking people from Terqa in the north. Some historians connect Mari's founding to the Kish civilization. This was a group of East Semitic-speaking people that stretched from Mesopotamia to Ebla.

At its peak, the second city of Mari had about 40,000 people. They spoke an East Semitic language very similar to Eblaite. During the Shakkanakku period, the people spoke an East Semitic Akkadian. West Semitic names started appearing in Mari during the second kingdom era. By the middle Bronze Age, the West Semitic Amorite tribes were the majority of the nomadic groups in the middle Euphrates and Khabur valleys. Amorite names were even seen among the ruling family toward the end of the Shakkanakku period.

During the Lim era, most of the people were Amorite. But there were also people with Akkadian names. Even though the Amorite language became the main spoken language, Akkadian was still used for writing. The nomadic Amorites in Mari were called the Haneans. This term generally meant nomads. These Haneans were split into two groups: the Banu-Yamina and the Banu-Simaal. The ruling family belonged to the Banu-Simaal group. The kingdom also had tribes of Suteans living in the Terqa area.

Mari was an absolute monarchy, meaning the king had total control. Scribes helped him manage everything. During the Lim era, Mari was divided into four provinces, plus the capital. Each province had its own government. The government provided villagers with farming tools. In return, they received a share of the harvest.

Culture and Beliefs

The first and second kingdoms of Mari were heavily influenced by the Sumerian south. The society was led by a group of powerful city leaders. Citizens were known for their fancy hairstyles and clothes. The calendar was based on a solar year with twelve months. It was the same calendar used in Ebla. Scribes wrote in Sumerian language. The art and architecture were very similar to Sumerian styles.

Mesopotamian influence continued in Mari's culture during the Amorite period. This is seen in the Babylonian writing style used in the city. However, this influence was less strong than before. A unique Syrian style became more common, especially in the kings' seals. Society was tribal, mostly made up of farmers and nomads. Unlike Mesopotamia, temples played a smaller role in daily life. Most power was held by the palace. Women had a good amount of equality with men. Queen Shibtu, for example, ruled for her husband when he was away. She had a lot of power over his top officials.

Mari's gods included both Sumerian and Semitic deities. For most of its history, Dagan was the main god. Mer was the city's special protector god. Other Semitic gods included Ishtar (goddess of fertility), Athtar, and Shamash (the Sun god). Shamash was very important and believed to know and see everything. Sumerian gods included Ninhursag, Dumuzi, Enki, Anu, and Enlil. Prophecy was important in society. Temples had prophets who advised the king and took part in religious festivals.

Economy and Trade

The first Mari had the oldest wheel workshop found in Syria. It was also a center for making bronze. The city had areas for melting metals, dyeing, and making pottery. They used charcoal brought by river boats from the upper Khabur and Euphrates areas.

The second kingdom's economy relied on both farming and trade. It was centrally organized. Grain was stored in shared granaries and given out based on social status. This organization also controlled the animal herds. Some groups, like metalworkers, textile makers, and military officials, received direct support from the palace. Ebla was an important trading partner and rival. Mari's location made it a key trading center between the Levant and Mesopotamia.

The Amorite Mari kept the older economic ways. It still relied heavily on farming along the Euphrates valley. The city remained a trading center for merchants from Babylonia and other kingdoms. Goods from the south and east were shipped north, northwest, and west by riverboat. The main trade was metals and tin from the Iranian Plateau, which were sent as far west as Crete. Other goods included copper from Cyprus, silver from Anatolia, wood from Lebanon, gold from Egypt, olive oil, wine, textiles, and even precious stones from modern Afghanistan.

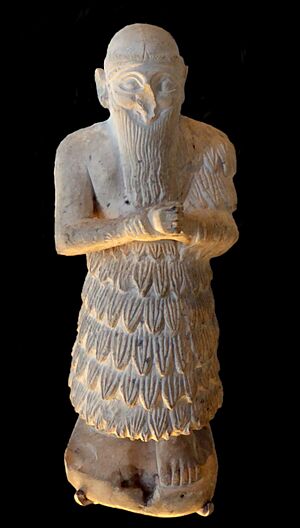

Discoveries and Records

Mari was discovered in 1933 in eastern Syria, near the Iraqi border. A Bedouin tribe was digging for a gravestone when they found a headless statue. When the news reached the French authorities, they investigated. Digging began on December 14, 1933, by archaeologists from the Louvre in Paris. The area where the statue was found was excavated, revealing the temple of Ishtar. This led to full-scale excavations. Archaeologists called Mari the "most westerly outpost of Sumerian culture."

Since the excavations began, over 25,000 clay tablets written in Akkadian cuneiform have been found. These discoveries are displayed in the Louvre, the National Museum of Aleppo, the National Museum of Damascus, and the Deir ez-Zor Museum. In the Deir ez-Zor Museum, a part of the Court of the Palms room from Zimri-Lim's palace has been rebuilt, including its wall paintings.

Mari has been excavated in many yearly campaigns since 1933. André Parrot led the first 21 seasons until 1974. He was followed by Jean-Claude Margueron (1979–2004) and Pascal Butterlin (starting in 2005).

The Mari Tablets

Over 25,000 tablets were found in Zimri-Lim's burnt library. They are written in Akkadian and cover a period of 50 years (around 1800 – 1750 BC). These tablets give us information about the kingdom, its customs, and the names of people who lived then. More than 3,000 are letters. The rest include texts about government, economy, and laws. Almost all the tablets are from the last 50 years of Mari's independence. Most have now been published. The language of the texts is official Akkadian. However, the names and grammar hints show that the common language of Mari's people was Northwest Semitic. Six of the tablets found were in the Hurrian language.

Current Situation

Excavations stopped in 2011 because of the Syrian Civil War. They have not restarted. The site came under the control of armed groups and suffered a lot of looting. A 2014 report showed that robbers were targeting the royal palace, public baths, and the temples of Ishtar and Dagan. Satellite images show that looting continued until at least 2017.

See also

- Tourism in Syria

- Cities of the Ancient Near East

- Short chronology timeline

- Statue of Iddi-Ilum

- Ornina

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |