Ebla facts for kids

Ruins of the outer wall and the "Damascus Gate"

|

|

| Alternative name | Tell Mardikh تل مرديخ |

|---|---|

| Location | Idlib Governorate, Syria |

| Coordinates | 35°47′53″N 36°47′53″E / 35.798°N 36.798°E |

| Type | settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 3500 BC |

| Abandoned | 7th century AD |

| Periods | Bronze Age |

| Cultures | Kish civilization, Amorite |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1964–2011 |

| Archaeologists | Paolo Matthiae |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

Ebla (which means "white rock" in Sumerian) was one of the very first kingdoms in Syria. Its ancient ruins are found at a place called Tell Mardikh, about 55 kilometers (34 miles) southwest of Aleppo. Ebla was a super important city during the Bronze Age, from around 3000 BC to 1600 BC.

When Ebla was discovered, it showed that the Levant (the area around the eastern Mediterranean Sea) was home to powerful, organized civilizations, just like Egypt and Mesopotamia. This changed what historians thought about the ancient world. Some even call the first Eblaite kingdom the first recorded world power!

Ebla started as a small village around 3500 BC. It grew into a huge trading empire and then a strong power that controlled much of northern and eastern Syria. Ebla was destroyed around 2300 BC but was rebuilt. This "second Ebla" was also destroyed around 2000 BC. Then, a group called the Amorites settled there, forming the "third Ebla." This kingdom also became a busy trade center. It was connected to Yamhad (modern-day Aleppo) until it was finally destroyed by the Hittite king Mursili I around 1600 BC.

Ebla stayed rich because it had a huge trading network. Archaeologists found items from places as far away as Sumer, Cyprus, Egypt, and even Afghanistan in its palaces. Ebla had its own language, Eblaite, and its government was different from Sumerian kingdoms. Women had a special place in society, and the queen had a lot of power in government and religious matters. The Eblaite gods were mostly from northern Semitic cultures, and some were unique to Ebla.

The city was first excavated in 1964. It became famous for the Ebla tablets, which are about 20,000 cuneiform clay tablets found there. These tablets date back to around 2350 BC. They were written in both Sumerian and Eblaite languages using cuneiform writing. These tablets have helped us understand the Sumerian language better and gave us important information about how people lived and how governments worked in the Middle Bronze Age Levant.

Contents

History of Ebla

The name "Ebla" might mean "white rock," which makes sense because the city was built on a limestone hill. Ebla was first settled around 3500 BC. It grew because it was a great place for international trade, especially for wool that was in high demand in Sumer. This early period is called "Mardikh I" by archaeologists and ended around 3000 BC. After that came the first and second kingdoms, from about 3000 to 2000 BC, known as "Mardikh II."

The First Kingdom: A Powerful Empire

|

First Eblaite Kingdom

Ebla

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 3000 BC–c. 2300 BC | |||||||

The first kingdom at its greatest extent, including vassals

|

|||||||

| Capital | Ebla | ||||||

| Common languages | Palaeo-Syrian | ||||||

| Religion | Ancient Levantine religion. | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||

|

• Established

|

c. 3000 BC | ||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

c. 2300 BC | ||||||

|

|||||||

| Today part of | Syria Lebanon Turkey |

||||||

The first kingdom of Ebla lasted from about 3000 to 2300 BC. It was the most important kingdom among the Syrian states, especially during the second half of the 3rd millennium BC. This time is often called "the age of the archives" because of the many Ebla tablets found.

Early Years and Conflicts

The early part of this period (3000-2400 BC) is called "Mardikh IIA." We learn about this time mostly from archaeological digs. Around 2700 BC, a royal palace called "G2" was built. Later, Ebla had a long war with Mari, another powerful city. Mari's king, Saʿumu, conquered many of Ebla's cities. But in the mid-25th century BC, Ebla's king Kun-Damu defeated Mari.

The Archive Period and Ebla's Power

The "archive period," called "Mardikh IIB1," lasted from about 2400 BC to 2300 BC. This period ended with the "first destruction" of Ebla, when the royal palace (Palace "G") and much of the city's high point were burned. During this time, Ebla was politically and militarily dominant over other Syrian city-states in northern and eastern Syria. Most of the tablets from this period are about money and trade, but some are royal letters and diplomatic documents.

The written records begin around the reign of Igrish-Halam, when Ebla had to pay tribute to Mari. Mari's king, Iblul-Il, even invaded many Eblaite cities. But Ebla recovered under King Irkab-Damu around 2340 BC. It became rich and fought back successfully against Mari. Irkab-Damu even made one of the earliest known peace and trade treaties in history with a city called Abarsal.

At its largest, Ebla controlled an area about half the size of modern Syria. This stretched from Ursa'um in the north to near Damascus in the south, and from Phoenicia in the west to Haddu in the east. Many parts of the kingdom were directly controlled by the king, while others were vassal kingdoms (meaning they were somewhat independent but had to obey Ebla). One of the most important vassals was Armi. Ebla had over sixty vassal kingdoms and city-states.

The vizier was the king's main official and had a lot of power. The most powerful vizier was Ibrium, who served for 18 years and led many military campaigns. During the reign of Isar-Damu, Ebla continued its war with Mari. Mari defeated Ebla's ally, Nagar, which blocked trade routes. Ebla also fought against rebellious vassals. To end the war with Mari, Isar-Damu allied with Nagar and Kish. The Eblaite vizier Ibbi-Sipish led their combined armies to victory near Terqa. Ebla was destroyed a few years after this campaign, probably after Isar-Damu's death.

The First Destruction of Ebla

The first destruction happened around 2300 BC. Palace "G" was burned, which actually helped preserve the clay tablets by baking them. There are different ideas about who destroyed Ebla:

- Akkadian Attack: Kings Sargon of Akkad and his grandson Naram-Sin of the Akkadian Empire both claimed to have destroyed a city called Ibla. Many scholars think Naram-Sin is the more likely one, as his inscriptions mention conquering "Armanum and Ebla" near the Mediterranean Sea.

- Mari's Revenge: Some scholars believe Mari destroyed Ebla to get revenge for its defeat at Terqa.

- Natural Disaster: Another idea is that a natural disaster, like a large fire, caused the destruction, as evidence of looting is not strong.

The Second Kingdom: A Rebirth

|

Second Eblaite Kingdom

Ebla

|

|

|---|---|

| c. 2300 BC–c. 2000 BC | |

Approximate borders of the second kingdom

|

|

| Capital | Ebla |

| Common languages | Palaeo-Syrian |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Historical era | Bronze Age |

|

• Established

|

c. 2300 BC |

|

• Disestablished

|

c. 2000 BC |

The second kingdom period, "Mardikh IIB2," lasted from 2300 to 2000 BC. It ended with Ebla's second destruction. Even though the Akkadians attacked northern Syria, they are not thought to be responsible for this destruction.

A new royal family ruled the second kingdom, but they kept many traditions from the first kingdom. A new royal palace was built in the lower part of the city. We don't know much about this period because very few written records have been found.

However, other ancient texts mention Ebla. For example, Gudea of Lagash (a city in Mesopotamia) asked for cedar wood from the "mountains of Ebla," showing Ebla's territory reached into modern-day Turkey. Texts from the Ur III empire also mention a ruler of Ebla, suggesting Ebla might have been a vassal (a state that pays tribute) to Ur.

The second kingdom fell apart around 2100 BC and ended with the city being burned down. The reason for this destruction is not fully known. Some think it might have been an invasion by the Hurrian people around 2030 BC.

The Third Kingdom: Under New Influence

|

Third Eblaite Kingdom

Ebla

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2000 BC–c. 1600 BC | |||||||

| Capital | Ebla | ||||||

| Common languages | Amorite language. | ||||||

| Religion | Ancient Levantine religion | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||

|

• Established

|

c. 2000 BC | ||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

c. 1600 BC | ||||||

|

|||||||

The third kingdom, "Mardikh III," lasted from about 2000 to 1600 BC. Ebla was quickly rebuilt as a planned city. New palaces, temples, and strong walls were constructed. The city was designed with straight lines, and large public buildings were erected.

The first known king of the third kingdom was Ibbit-Lim. A statue with his name was found in 1968, which helped archaeologists confirm that Tell Mardikh was indeed ancient Ebla. Since his name is Amorite, it's likely that most people in the third kingdom were Amorites, a group that was common in Syria at that time.

By the early 18th century BC, Ebla became a vassal of Yamhad, a powerful Amorite kingdom based in Aleppo. We don't have many written records from this time. However, one Eblaite ruler named Immeya received gifts from the Egyptian Pharaoh Hotepibre, showing Ebla still had important connections. An Eblaite princess even married a son of a king from Alalakh, a city connected to Yamhad.

Ebla was finally destroyed by the Hittite King Mursili I around 1600 BC. Indilimma was probably Ebla's last king.

Later Times

Ebla never fully recovered after its third destruction. It became a small village and was mentioned as a vassal to the Idrimi dynasty of Alalakh. It continued as a rural settlement through the Iron Age and later periods, until it was completely abandoned around the 7th century AD.

The City of Ebla

Ebla was built with a lower town and a raised area in the center called the acropolis. During the first kingdom, the city covered about 56 hectares (138 acres) and was protected by strong mud-brick walls. Ebla was divided into four areas, each with its own gate. The acropolis had the king's palace ("G") and one of two temples dedicated to the god Kura. The lower city had the second Kura temple.

During the third kingdom, Ebla grew to nearly 60 hectares (148 acres) and was protected by a fortified wall with double gates. The acropolis was also fortified. A new royal palace ("E") was built on the acropolis, and a temple for the goddess Ishtar was constructed over older temples. The lower town was still divided into four areas, with different palaces and temples built over time.

Other important buildings in the third kingdom included the vizier's palace, the western palace, and temples dedicated to gods like Shamash, Rasap, and Hadad.

Royal Burials

Kings of the first kingdom were buried outside the city. However, one royal tomb from the first kingdom was found in Ebla itself, beneath the royal palace "G." This might show that Eblaites started to adopt the Mesopotamian tradition of burying kings under their palaces.

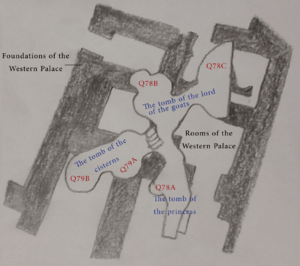

The royal burial ground for the third kingdom was found under Palace "Q" (the western palace). These tombs were natural caves in the rock beneath the palace. They date from the 19th and 18th centuries BC.

Hypogeum G4

This royal tomb was found in the royal palace "G" and dates to the archive period, likely during King Isar-Damu's reign. It's very damaged, and most of its stones are gone. No bones or burial items were found, so it might have been robbed, never used, or built as a memorial.

Western Palace Tombs

These tombs were found under Building Q.

- The Tomb of the Princess: This is the oldest and smallest of the third kingdom tombs, dating to about 1800 BC. It was found in 1978 and contained the remains of a young woman. It was the only tomb not robbed and had valuable jewelry and burial objects.

- The Tomb of the Cisterns: This tomb is the most damaged. It had two burial rooms. It was likely the resting place of a king, as a club (a symbol of royal power) was found there.

- The Tomb of the Lord of the Goats: This is the largest tomb. It's called this because a throne decorated with bronze goat heads was found inside. A silver cup with King Immeya's name was also found, suggesting he was buried there.

Government and Society

The first kingdom of Ebla was ruled by a king (called Malikum) and a grand vizier. The vizier led a council of elders and the government. The second kingdom was also a monarchy, but we know less about it. The third kingdom was a city-state monarchy, but it was less powerful and under the control of Yamhad.

How the First Kingdom Was Run

The queen shared power with the king. The crown prince handled internal matters, and the second prince dealt with foreign affairs. Most duties, including military ones, were managed by the vizier and a large government team. The city was divided into four areas, each with its own chief inspector. The king also had special agents, collectors, and messengers.

Regions and Rulers

Many smaller kingdoms were loyal to Ebla. These vassal kings had a lot of freedom but paid tribute and provided military help. The capital's administrative center was called the "SA.ZA," which included the royal palaces and storerooms. Areas outside the capital were called "uru-bar" (meaning "outside of the city").

- Lugal: In Mesopotamia, "lugal" meant king, but in Ebla, it meant a governor directly under the capital's authority. These governors ruled cities directly controlled by Ebla and brought goods to Ebla's storehouses.

- Ugula: This title means superintendent. Some "ugulas" were independent rulers, while others were the main administrators of tribal groups.

The Core Region

The areas directly controlled by the king that were important for the capital's economy are called the "chora." This core region of Ebla was about 3000 square kilometers (1158 square miles). It included cities and villages where the king or vizier had palaces, important religious sites, and towns where textiles were delivered.

People, Language, and Culture

Life in the First and Second Kingdoms

The first and second kingdoms shared a similar culture. During the archive period (2400-2300 BC), about 40,000 people lived in the capital, and over 200,000 in the whole kingdom. The people of Ebla spoke a Semitic language. Some scholars think the Eblaite language was a West Semitic language, while others believe it was an East Semitic dialect, similar to Akkadian language. Today, most experts agree it was an East Semitic language with features from both West and East Semitic.

Ebla had many religious and social festivals, including long rituals for a new king. Their calendars were based on the sun's year, divided into twelve months. Two calendars were found. Many months were named after gods. Each year was given a name instead of a number.

Women in Ebla had equal pay to men and could hold important government jobs. Eblaites imported special animals called Kungas (a type of donkey-like animal) from Nagar. They used them to pull royal carriages and gave them as gifts to allied cities. Eblaite society was less focused on the palace and temple compared to Mesopotamian kingdoms. The Eblaite palace was open to the city, making the government more accessible. Music was important, and musicians were hired from other cities like Mari. Ebla also hired acrobats.

Life in the Third Kingdom

The people of the third kingdom were mostly Amorites, a Semitic group. The Amorites had been neighbors and rural subjects in the first kingdom, and they became dominant after the second kingdom's fall. The city saw a lot of new construction, with many palaces, temples, and fortifications built. The Amorite-speaking Eblaites worshiped many of the same gods as earlier Eblaites and kept the acropolis as a sacred place. The third kingdom's art and ideas about kingship were influenced by Yamhad's culture.

Economy and Trade

During the first kingdom, the palace controlled the economy, but rich families also managed their own money. The palace gave food to its workers. About 40,000 people were part of this system. Unlike Mesopotamia, land generally stayed with villages, who paid a yearly share to the palace. Farming was mostly about raising animals, with large herds of cattle, sheep, and goats managed by the palace.

Ebla became rich through trade. Its wealth was similar to the most important Sumerian cities. Mari was its main trade rival. Ebla likely traded timber from nearby mountains and textiles. Handicrafts were also a major export. Ebla had a wide trade network that reached as far as modern-day Afghanistan. It sent textiles to Cyprus, possibly through the port of Ugarit. Most of its trade went by river-boat to Mesopotamia, especially to Kish. The main palace "G" had items from Ancient Egypt, including names of pharaohs Khafre and Pepi I.

Ebla continued to be a trade center during the second kingdom. Trade remained Ebla's main economic activity during the third kingdom, with archaeological finds showing extensive trade with Egypt and coastal Syrian cities like Byblos.

Religion and Beliefs

Ebla was a polytheistic state, meaning they worshiped many gods. During the first kingdom, Eblaites also honored their dead kings. Their gods often came in pairs, like a god and his female partner. Eblaites mostly worshiped North-Western Semitic gods, and some gods were unique to Ebla. For example, Hadabal and his partner Belatu were unique to Ebla, as was Kura, the city's patron god, and his partner Barama.

Other gods included the Syrian goddess Ishara, who was very important to the royal family. Ishtar was also worshiped, but less often than Ishara. Other deities were Damu, the Mesopotamian god Utu, Ashtapi, Dagan, Hadad (Hadda) and his partner Halabatu, and Shipish, the sun goddess. The four city gates were named after the gods Dagan, Hadda, Rasap, and Utu. In total, about 40 gods received offerings.

During the third kingdom, the Amorites worshiped common northern Semitic gods. The unique Eblaite gods disappeared. Hadad became the most important god, and Ishtar took Ishara's place as the city's main goddess after Hadad.

Ebla and the Bible

When the Ebla tablets were first being translated, some scholars, like Giovanni Pettinato, thought there might be connections between Ebla and the Bible. They suggested the tablets mentioned Yahweh, the Patriarchs, and Sodom and Gomorrah. However, most experts now agree that these early ideas were based on guesses and that Ebla does not directly connect to these Biblical stories. Today, Ebla is studied as its own unique ancient civilization.

Discovery of Ebla

In 1964, Italian archaeologists from the University of Rome La Sapienza, led by Paolo Matthiae, started digging at Tell Mardikh. In 1968, they found a statue dedicated to the goddess Ishtar with the name of Ibbit-Lim, who was a king of Ebla. This helped them confirm that the site was indeed the ancient city of Ebla, which was known from other ancient writings.

In the next ten years, the team discovered a large palace (Palace G) from around 2500-2000 BC. Inside the palaces, they found small sculptures made of valuable materials like Lapis lazuli, black stones, and gold. They also found about 17,000 pieces of cuneiform tablets. When put together, these make about 2,500 complete tablets, making Ebla's archive one of the largest from the 3rd millennium BC.

About 80% of the tablets were written using Sumerian signs, but the others used Sumerian cuneiform to write a new Semitic language, which was named "Eblaite." They also found Sumerian/Eblaite dictionaries, which helped translate the tablets. These tablets give us important information about the culture, economy, and politics of northern Mesopotamia around the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. They also tell us about daily life, government income, diplomatic messages, school texts, hymns, and myths.

The Ebla Library

The Ebla tablets, over 4000 years old, are part of one of the oldest libraries ever found. This collection of records was at least 500 years older than any other found before. There is evidence that the tablets were organized and classified. The larger tablets were originally stored on shelves but fell when the palace was destroyed. By looking at where they fell, archaeologists could figure out their original positions and saw that they were organized by subject.

This careful organization was not seen in earlier Sumerian digs. The advanced ways of arranging texts show that libraries and archives are much older than people thought before Ebla was discovered. A large part of the tablets are literary and educational texts. This suggests the collection was also a true library, not just a place for government records. The tablets show early examples of texts being copied into other languages, classified, cataloged, and arranged by size and content. The Ebla tablets have given scholars new ideas about how library practices began 4,500 years ago.

Most of the recovered tablets are stored at the Idlib Regional Museum in Syria. Their current condition is unknown due to recent conflicts.

Ebla's Legacy

Ebla's first kingdom is a great example of early organized states in Syria. Some scholars, like Samuel Finer and Karl Moore, even consider it the first recorded world power. The discovery of Ebla changed the idea that Syria was just a bridge between Mesopotamia and Egypt. It proved that the region was a center of civilization on its own.

Ebla During the Syrian Civil War

Due to the Syrian Civil War, excavations at Ebla stopped in March 2011. By 2013, the site was controlled by an armed group. They used its high location as an observation point and tried to protect it from looting. However, many tunnels were dug by robbers looking for valuable items. They scattered human remains from tombs. Nearby villagers also started digging to find and steal artifacts.

The site was taken by the Syrian Armed Forces on January 30, 2020.

See also

In Spanish: Ebla para niños

In Spanish: Ebla para niños

- Azi (scribe)

- Biblical archaeology

- Cities of the Ancient Near East

- Mari, Syria

- Short chronology timeline

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |