History of ancient Israel and Judah facts for kids

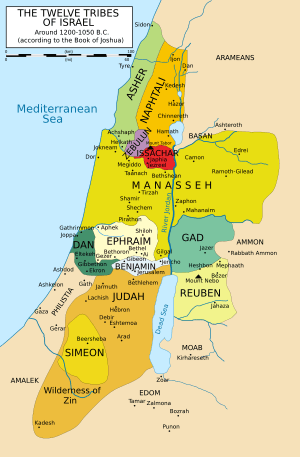

Israel and Judah were two ancient kingdoms from the Iron Age in the Near East. This story covers the time from when the name "Israel" first appeared in history around 1200 BCE, up to when the independent kingdom of Judah ended, close to the time of Jesus.

These two kingdoms were located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. This area was a narrow strip of land, about 100 miles long and 40-50 miles wide. It was a busy crossroads between powerful empires like Egypt to the south, and Assyria, Babylonia, and later Persia to the north and east. Across the sea to the west were Greece and later Rome.

Israel and Judah grew out of the Canaanite culture from the late Bronze Age. They started as small villages in the southern highlands of the Levant (the area between the coast and the Jordan River) between 1200 and 1000 BCE. Israel became a strong local power in the 800s and 700s BCE, but then it was conquered by the Assyrians. The southern kingdom, Judah, became wealthy while under the control of larger empires. However, a revolt against Babylon led to its destruction in the early 500s BCE.

People from Judah who were forced to leave (called exiles) returned from Babylon when the Persian Empire took over. They started a new community in the area, which was now called Yehud. Later, Yehud became part of the Greek kingdoms that formed after Alexander the Great conquered the region. In the 100s BCE, the Jews fought against Greek rule and created the Hasmonean kingdom. This kingdom later became a Roman territory and eventually part of the Roman Empire.

Contents

Life in the Late Bronze Age (1550-1200 BCE)

Where people lived and settled

The eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, known as the Levant, stretches about 400 miles from north to south. It's about 70 to 100 miles wide, between the sea and the Arabian desert. The southern part of this coast has a flat area and foothills called the Shephalah. East of these areas are mountains, known as the "hill country of Judah" in the south and "hill country of Ephraim" further north, then Galilee and the Lebanon mountains.

Even further east is the deep valley of the Jordan River, the Dead Sea, and the Arabah valley, which goes down to the Red Sea. Beyond that is the Syrian desert, separating the Levant from Mesopotamia. To the southwest is Egypt, and to the northeast is Mesopotamia. This narrow strip of land was often fought over by stronger empires.

In ancient times, the northern and central parts of the Levantine coast were called Phoenicia. The southern part was known to the Egyptians as Canaan, which meant all their lands in Asia. In the Bible, Canaan can mean all the land west of the Jordan River, or just the coastal strip. Later, the name Canaan was replaced by "Philistia," meaning "Land of the Philistines," even though the Philistines were gone. The modern name "Palestine" comes from this.

During the Late Bronze Age, most people lived near the coast and along major trade routes. The central hill-country had very few people. Each city had its own ruler, who often argued with neighbors and asked the Egyptians to help settle disputes. Jerusalem was one of these Canaanite cities. Letters from Egyptian records show it was a small city with farms and villages around it. Unlike many other cities, it doesn't seem to have been destroyed at the end of this period.

The collapse of the Bronze Age

In the 1200s BCE, Canaan had people from different backgrounds, but they shared a common system of city-states controlled by Egypt. Then, Egyptian power and the Canaanite city-state system suddenly collapsed. After this collapse, two new groups appeared in the 1100s BCE: the Israelites in the hill country and the Philistines on the southern coast.

The Philistines were clearly outsiders, probably from Cyprus, with their own unique culture. The Israelites, however, were from Canaan itself. For example, the Hebrew spoken by people in Judah and Israel in the early 900s BCE was similar to the languages of Phoenicia, Ammon, Moab, and Edom.

The reasons for the Bronze Age collapse, which affected the entire eastern Mediterranean, are not fully known. Drought, hunger, and other problems might have caused many people to move around. Whatever the cause, several important Canaanite cities were destroyed over more than a century. Canaanite culture was slowly taken over by the Philistines, Phoenicians, and Israelites.

Early Iron Age (1200-586 BCE)

The first Iron Age (1200-1000 BCE)

The Merneptah stele, a stone slab made by an Egyptian pharaoh around 1200 BCE, has the first written mention of the name Israel. It says: "Israel is laid waste and his seed is not." This "Israel" was likely a group of people living in the northern part of the central highlands.

As things became chaotic, people moved to the previously empty highlands. Surveys have found over 300 small settlements there during this time. Most were new, and the largest had no more than 300 people. The villages were bigger and more numerous in the northern areas (like biblical Manasseh and Ephraim). The total population at the start of this period was about 20,000, and it doubled by the end.

Villages from this time, with features like four-room houses and water cisterns, are considered Israelite when found in the highlands. However, it's hard to tell them apart from Canaanite sites of the same period. It's also hard to tell the difference between Hebrew and Canaanite writings until the 900s BCE.

In this period, the highlands showed no signs of a central government, temples, or organized worship. One small difference between the highland "Israelite" villages and Canaanite sites is that Israelite sites have almost no pig bones. But it's debated whether this means they were a different ethnic group or if there were other reasons.

During this same time, new kingdoms rose to the east of the northern hill country: Aram Damascus and Ammon, then Moab (east of the Dead Sea), and Edom (south of the Dead Sea).

The second Iron Age (1000-586 BCE)

An inscription from the Egyptian pharaoh Shoshenq I (likely the biblical Shishak) describes military campaigns in the area north of Jerusalem in the late 900s BCE. About a hundred years later, in the 800s BCE, the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III listed Ahab of Israel among his enemies at the battle of Qarqar (853 BCE). The Mesha stele (around 830 BCE) tells of a Moabite king celebrating his freedom from the "House of Omri" (meaning Israel).

Similarly, the Tel Dan stele mentions the death of an Israelite king, probably Jehoram, killed by an Aramean king around 841 BCE. Digs at Samaria, the capital of Israel, show that it was a powerful, organized kingdom in the northern highlands during the 800s and 700s BCE. In the late 700s BCE, King Hoshea of Israel rebelled against the Assyrians and was defeated around 722 BCE. Some people were sent away, new settlers were brought in, and Israel became an Assyrian province.

The first proof of an organized kingdom in the southern region comes from the mid-800s BCE Tel Dan stele. It mentions the death of a king from the "House of David" along with the king of Israel. The Mesha stele from the same time might also mention the House of David, but this is debated. It's generally thought that this "House of David" is the same as the royal family in the Bible.

However, archaeological surveys show that in the 900s and 800s BCE, Jerusalem was just one of four large villages in the area. It didn't seem more important than its neighbors. It was only in the late 700s BCE that Jerusalem grew very quickly. Its population became much larger than ever before, and it clearly became the most important city among the surrounding towns.

Some scholars used to think this growth was because refugees from Israel came after the Assyrians conquered it (around 722 BCE). But a newer idea is that it was a joint effort between Assyria and the kings of Jerusalem. They wanted to make Judah a state loyal to Assyria, controlling the valuable olive oil industry.

The sudden fall of Assyrian power in the late 600s BCE led to King Josiah trying to make Judah independent. This failed, and Jerusalem was destroyed by Assyria's successor, the Neo-Babylonian Empire, in 587/586 BCE.

After the Exile (586 BCE - 70 CE)

Babylonian and Persian times (586-333 BCE)

In 586 BCE, the Babylonians, led by King Nebuchadnezzar II, captured Jerusalem. They destroyed the Temple of Solomon, ended the rule of David's family, and took many people away as captives. Only the poorest people were left in Judah, which was now the Babylonian province of Yehud. Its capital was at Mizpah, north of Jerusalem.

A few years later, the governor of Yehud was murdered, causing more people to flee, this time to Egypt. So, by about 580 BCE, people from Judah were in three places: the leaders in Babylon (where they seemed to be treated well), a large group in Egypt, and a small group left in Judah.

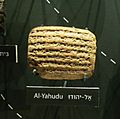

The Exile ended when Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered Babylon (around 538 BCE). The Persians made Judah/Yehud a province called "Yehud medinata" within their larger empire. Over the next century, some of the exiles returned to Jerusalem. They eventually rebuilt the Second Temple (around 516/515 BCE). For over a hundred years, the main administrative city remained Mizpah. Meanwhile, Samaria continued as the province of Semarina in the same larger Persian region as Yehud.

The Persian Period

In 539 BCE, the Persians conquered Babylon. In 537 BCE, they began the Persian period of Jewish history. In 520 BCE, Cyrus the Great allowed Jews to return to Judea and rebuild the Temple (finished 515 BCE). He appointed Zerubbabel, a grandson of the second-to-last Judean king, as governor. However, he did not allow the kingdom to be restored.

Without a powerful king, the Temple became more important, and priests became the main authority. But the Second Temple was built under foreign rule, and some questioned its legitimacy. This led to different groups (sects) forming within Judaism over the centuries, each claiming to represent the true "Judaism." Most of these groups discouraged mixing, especially marriage, with members of other groups.

The end of the Babylonian Exile saw not only the building of the Second Temple but also, according to one theory, the final version of the Torah. Even though priests controlled the Temple, scribes and wise people (who later became rabbis) focused on studying the Torah. Starting from the time of Ezra, the Torah was read publicly on market days. These wise people developed and kept an oral tradition alongside the written Holy Scriptures.

Greek and Roman times (333 BCE-70 CE)

The Hellenistic period started in 332 BCE when Alexander the Great conquered Persia. After he died in 323 BCE, his empire was split among his generals. At first, Judea was ruled by the Egyptian-Greek Ptolemies. But in 198 BCE, the Syrian-Greek Seleucid Empire, led by Antiochus III, took control of Judea.

During the Hellenistic Period, the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) was put into its final form, according to one idea. New sacred traditions also appeared outside the Bible. The earliest signs of Jewish mysticism are found around the book of Ezekiel, written during the Babylonian Exile. However, most known mystical texts were written at the end of the Second Temple period. Some scholars believe that the secret traditions of the Kabbalah (Jewish Mysticism) were influenced by Persian beliefs, Platonic philosophy, and Gnosticism.

The Near East was a place where many cultures mixed, especially during the Hellenistic period. Several languages were spoken. Jews almost certainly spoke Aramaic among themselves. Greek was often used across the eastern Mediterranean. Judaism was changing quickly, reacting and adapting to a larger political, cultural, and intellectual world. This also made non-Jews interested in Judaism.

Many Jews lived outside Judea (in the Diaspora), and the Jewish areas of Judea, Samaria, and Galilee had many non-Jews (Gentiles) who were often interested in Judaism. Jews had to live with the values of Hellenism and Greek philosophy, which often clashed with their own traditions. Generally, Greek culture saw itself as bringing civilized ways to people they thought were isolated or behind the times.

For example, Greek-style bath houses were built near the Temple in Jerusalem. Even in Jerusalem, the gymnasium became a place for social, athletic, and intellectual life. Many Jews, including some wealthy priests, adopted these new ways.

At the same time, Jews faced a challenge in their own beliefs: their Torah laws applied only to them and to converts, but they believed their God was the only God of everyone. This led to new ways of understanding the Torah, some influenced by Greek ideas and in response to Gentile interest in Judaism. During this time, many ideas from early Greek philosophy entered or influenced Judaism, leading to debates and different groups within the religion.

In 331 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire. After his death in 323 BCE, his empire broke apart, and the province of Yehud became part of Egypt's kingdom, ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty. Ptolemaic rule was gentle. Alexandria became the largest Jewish city in the world, and Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt (281-246 BCE) supported Jewish culture, sponsoring the Septuagint translation of the Torah. This period also saw the start of the Pharisees and other Jewish groups like the Sadducees and Essenes.

But in the early 100s BCE, Yehud fell to the Seleucid Syrian ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes (174-163 BCE). Unlike the Ptolemies, Antiochus tried to force the Jews to adopt Greek ways. His disrespect for the Temple sparked a rebellion, which ended with the Syrians being driven out and the Temple being rededicated under the Maccabees.

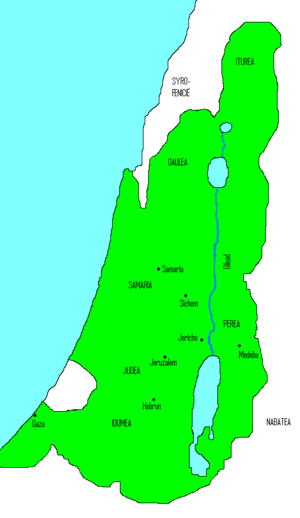

The kingdom started by the Maccabees tried to bring back the Judah described in the Bible: a Jewish kingdom ruled from Jerusalem, covering all the lands once ruled by David and Solomon. To do this, the Hasmonean kings conquered (and forced to convert to Judaism) the people of Moab, Edom, and Ammon, as well as the land of the lost kingdom of Israel.

Generally, Jews accepted foreign rule if they only had to pay taxes and were allowed to govern themselves. However, Jews were divided between those who liked Greek culture and those who opposed it. They were also divided over whether to support the Ptolemies or the Seleucids. When the High Priest Simon II died in 175 BCE, a conflict started between his son Onias III (who opposed Greek culture and favored the Ptolemies) and his son Jason (who favored Greek culture and the Seleucids).

A period of political plotting followed, with priests like Menelaus bribing the king to become High Priest. There were also accusations of murder among those competing for the title. This led to a short civil war. Many Jews supported Jason. In 167 BCE, the Seleucid king Antiochus IV invaded Judea, entered the Temple, and took its money and sacred items. Jason fled to Egypt. Antiochus then forced Jews to abandon their laws and customs, threatening to kill them if they refused.

At this point, Mattathias and his five sons, who were priests from the Hasmon family in the village of Modein, led a bloody but successful revolt against the Seleucids. Judah Maccabee freed Jerusalem in 165 BCE and restored the Temple. Fighting continued, and Judah and his brother Jonathan were killed. In 141 BCE, an assembly of priests and others confirmed Simon as high priest and leader, creating the Hasmonean dynasty. When Simon was killed in 135 BCE, his son John Hyrcanus took his place as high priest and king.

The Hasmonean kingdom

After defeating the Seleucid forces, John Hyrcanus started a new kingdom with the priestly Hasmonean family in 152 BCE. This meant priests became political leaders as well as religious ones. Even though the Hasmoneans were seen as heroes for fighting the Seleucids, some people felt their rule wasn't truly legitimate because they weren't from the family of King David, who ruled during the First Temple Era.

Sadducees, Essenes, and Pharisees

The gap between priests and wise teachers grew during the Hellenistic period as Jews faced new political and cultural challenges. Around this time, the Sadducees emerged as the party of the priests and wealthy leaders. The name Sadducee comes from Zadok, the high priest of the First Temple.

The Essenes were another early religious group. They are believed to have rejected either the high priests appointed by the Seleucids or the Hasmonean high priests, seeing them as wrong. They soon rejected the Second Temple, believing that their own Essene community was the new Temple, and that following the law was a new form of sacrifice.

Even though the Essenes' lack of concern for the Second Temple separated them from most Jews, their idea that sacredness could exist outside the Temple was shared by another group, the Pharisees ("separatists"). This group was based among the scribes and wise teachers. The meaning of their name is not fully clear.

During the Hasmonean period, the Sadducees and Pharisees mostly acted as political parties. The Essenes were not as focused on politics. The political differences between the Sadducees and Pharisees became clear when the Pharisees demanded that the Hasmonean king Alexander Jannai choose between being king and being High Priest in the traditional way. This demand led to a short civil war that ended with a harsh crackdown on the Pharisees. However, on his deathbed, the king asked for the two groups to make peace. Alexander was succeeded by his widow, whose brother was a leading Pharisee. After her death, her older son, Hyrcanus II, sought Pharisee support, and her younger son, Aristobulus, sought the support of the Sadducees.

In 64 BCE, the Roman general Pompey took over Jerusalem and made the Jewish kingdom a client (a state controlled by) of Rome. In 57-55 BCE, Aulus Gabinius, a Roman governor, divided the area into Galilee, Samaria, and Judea. Each had five local councils of law called Sanhedrin. In 40-39 BCE, Herod the Great was appointed King of the Jews by the Roman Senate. But in 6 CE, his successor, Herod Archelaus, was removed by the emperor Augustus, and his lands were taken over as the Iudaea Province under direct Roman rule. This marked the end of Judah as an independent kingdom.

Ancient Beliefs

Israel and Judah had beliefs that came from the religion of ancient Canaan, which in turn had roots in the religion of Ugarit from the 1000s BCE. In those times, people believed in many gods, often seen as a council or family of divine beings.

See also

|

Notable people |

Kings of Israel | |

|---|---|---|

| David, Solomon,Ahab, Ahaziah | ||

| Kings of Judah | ||

| Hezekiah, Josiah, Jehoahaz |

Images for kids

-

A carving showing Jehu, King of Israel, giving gifts to the Mesopotamian King Shalmaneser III of Assyria. This is from the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (around 841-840 BCE).

-

The growth of the Hasmonean kingdom.

-

A modern model of what the Second Temple might have looked like after it was rebuilt during the rule of Herod I.

-

The Magdala stone, found in the ancient city of Magdala. Two ancient synagogues from the 1st century CE were found in Magdala.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del antiguo Israel para niños

In Spanish: Historia del antiguo Israel para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |