Uruk period facts for kids

|

|

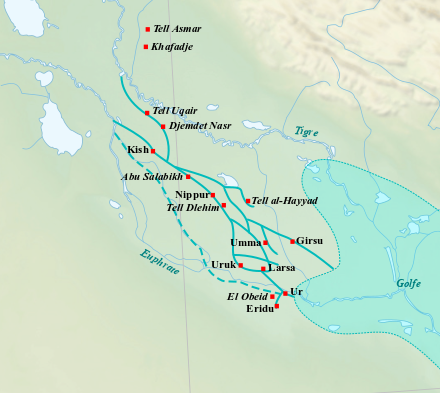

| Geographical range | Mesopotamia |

|---|---|

| Period | Copper Age |

| Dates | c. 4000–3100 BC |

| Type site | Uruk |

| Preceded by | Ubaid period |

| Followed by | Jemdet Nasr period |

The Uruk period (around 4000 to 3100 BC) was an important time in the history of Mesopotamia. It came after the Ubaid period and before the Jemdet Nasr period. This period is named after the ancient city of Uruk. During this time, cities first appeared in Mesopotamia. This is also when the Sumerian civilization began to grow.

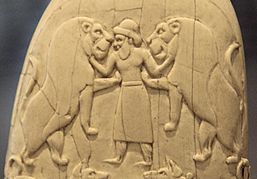

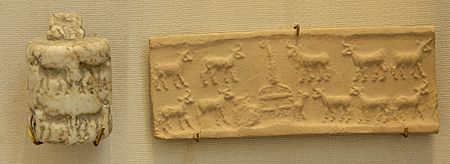

In the later part of the Uruk period (from the 34th to 32nd centuries BC), the first forms of writing slowly started to appear. This time is also called the "Protoliterate period." During the Uruk period, people used less painted pottery. Instead, copper became more popular. People also started using cylinder seals a lot.

Contents

- Understanding the Uruk Period Timeline

- Southern Mesopotamia: The Heart of Uruk Culture

- Uruk's Neighbors and Influence

- The Uruk Expansion: Why Did It Happen?

- Egypt and Mesopotamia Connections

- Society and Culture in the Uruk Period

- The End of the Uruk Period

Understanding the Uruk Period Timeline

Experts first used the name "Uruk period" in 1930. They also named the periods before and after it. Figuring out the exact dates for the Uruk period is tricky. It covered most of the 4th millennium BC. But, there is no full agreement on when it started or ended. It is also hard to know the exact changes within the period.

This is because the original digs in Uruk happened a long time ago. They were done in the 1930s, before modern dating methods existed. This makes it hard to compare findings from different sites.

The Uruk period is usually split into a few stages. The first two are "Old Uruk" and "Middle Uruk." These early stages are not very well known. Their exact dates are also unclear.

The "Late Uruk" period is the best known. It started around the middle of the 4th millennium BC. It lasted until about 3200 or 3100 BC. During this time, the Uruk civilization really grew. There was a lot of new technology. Big cities with huge buildings appeared. Governments began to form. The Uruk culture also spread across the Near East.

The Jemdet Nasr Period: A New Phase

After the "Late Uruk" period came the Jemdet Nasr period. During this time, the Uruk civilization became less powerful. Different local cultures started to grow across the Near East. Some experts call this the "Final Uruk" period. It lasted from about 3000 to 2900 BC.

Other Ideas for the Timeline

In 2001, new ideas for the Uruk period timeline came out. These were based on newer digs outside Mesopotamia. They called the Uruk period the "Late Chalcolithic" (LC). This new timeline also divided the "Old Uruk" into two parts.

Even with some unclear dates, most experts agree on the general timeline. The Uruk period lasted about 1000 years, from 4000 to 3000 BC. It had different phases. First, cities started to form. Then, the Uruk culture expanded. It reached its peak during the Late Uruk period. After that, Uruk's influence lessened. Local cultures grew stronger.

Some researchers think new groups of people, like the future Akkadians, arrived. But there is no clear proof of this. In southern Mesopotamia, this time is known as the Jemdet Nasr period. People started living closer together. Power structures also changed.

Southern Mesopotamia: The Heart of Uruk Culture

Southern Mesopotamia was the main area for the Uruk culture. It seems to have been the cultural center of that time. This is where the biggest buildings and clearest signs of city life appeared. The first writing system also started here. The culture from this region greatly influenced the rest of the Near East.

However, we do not know a lot about this region from archaeological digs. Only the city of Uruk itself has shown large buildings and old documents. These show why Uruk was so important. Other sites have some buildings, but they are not as well known. So, we cannot be sure if Uruk was truly unique or if it just seems that way because of where digs happened.

This region was very good for farming. People used irrigation systems that grew in the 4th millennium BC. They mainly grew barley, date palms, and other fruits. They also raised sheep for wool. Even though the area had no metal resources and was dry, it had good natural advantages. It was a flat delta with many waterways. This made farming easy. It also made travel by river or land simple.

This area likely became very populated and urbanized in the 4th millennium BC. It had different social classes, skilled workers, and long-distance trade. Researchers like Robert McCormick Adams Jr. have studied this area. His work helped us understand how cities grew here. They found that some settlements became very important. Uruk seemed to be the most important by far. It was an early example of a very large city that grew at the expense of its neighbors.

We are not sure about the different groups of people living here during the Uruk period. This is linked to the question of where the Sumerians came from. Some believe the earliest writing was in Sumerian. If so, the Sumerians were already there. It is not clear if other groups, like the ancestors of the Akkadians, were also present.

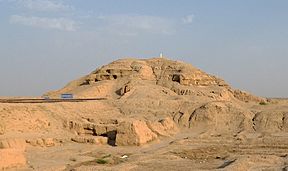

Uruk: The First Great City

Of all the cities, Uruk was by far the largest. It is the city that gives the period its name. At its peak, during the Late Uruk period, it covered 230–500 hectares. This was much bigger than other cities at the time. It may have had 25,000 to 50,000 people. The city had two main groups of huge buildings, about 500 meters apart.

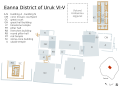

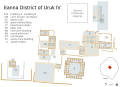

The most amazing buildings were in an area called the Eanna. After a building called the 'Limestone Temple' (from level V), a huge building project started in level IV. These new buildings were much larger than before. They had new designs and new ways of building and decorating. Level IV of the Eanna had two main groups of buildings. One had a 'Temple with mosaics' made of painted clay cones. The other had very large structures like the 'Hall with Pillars' and 'Hall with Mosaics'. There was also a large 'Grand Court' and two huge buildings called 'Temple C' and 'Temple D'. Temple D was the biggest building known from the Uruk period.

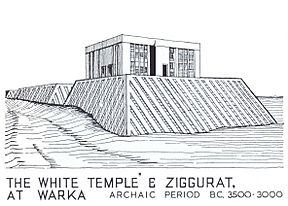

The second group of large buildings was for the god Anu. It had several temples built on a high platform. The "White Temple" from level IV is the best preserved. It was named for its white walls.

We are not sure what these huge buildings were used for. They were much bigger than anything seen before. Some thought they were all 'temples'. This was because later, the Eanna area was for the goddess Inanna and the other area for the god An. But it is also possible they were a mix of buildings for power. These could include royal homes, offices, and chapels. Building them took a lot of effort. This shows how powerful the leaders of this time were.

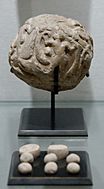

Uruk is also where many early writing tablets were found. These were from levels IV and III. They were found in a trash area, so we don't know exactly how they were used. In the Jemdet Nasr period (Uruk III), the Eanna area was completely rebuilt. The old buildings were torn down. A large terrace was built over them. In the foundations, they found a special collection of items. These included important artworks like a large vase and cylinder seals.

Uruk's Neighbors and Influence

The Uruk culture spread over a huge area. This included all of Mesopotamia and nearby regions. It reached central Iran and southeastern Anatolia. The main Uruk culture was in southern Mesopotamia. But its influence, called the "Uruk expansion," reached many other places.

Some areas had very clear Uruk influence. These include Upper Mesopotamia, northern Syria, western Iran, and southeastern Anatolia. These regions also saw cities and larger governments grow. They were strongly influenced by Uruk culture in the late period (around 3400–3200 BC). After that, their own local cultures became stronger.

Susiana and the Iranian Plateau

The region around Susa in southwest Iran was very close to southern Mesopotamia. It was strongly influenced by Uruk culture. This might have been from conquest or from cultures slowly mixing. Susa became a city during the Uruk period. It had large buildings, including a 'High Terrace'.

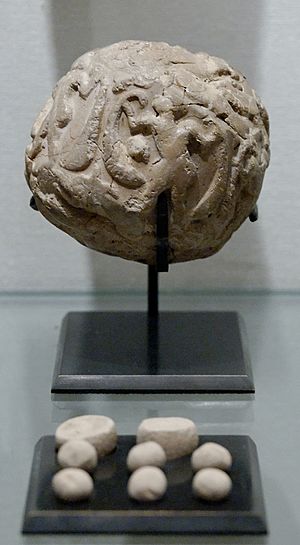

The objects found at Susa are very important. They show us the art of the Uruk period. They also show the start of administration and writing. The cylinder seals from Susa have many pictures. They show daily life and a local leader. These seals, along with clay tokens, show how administration and accounting grew at Susa. Susa also has some of the oldest writing tablets. Other sites in this area, like Jaffarabad and Chogha Mish, also have Uruk period findings.

Further north, at Godin Tepe in the Zagros mountains, Level V belongs to the Uruk period. It had a wall around buildings. The objects found there are similar to Late Uruk and Susa. This site might have been a trading post for merchants from Susa or Mesopotamia. They were likely interested in trade routes for tin and lapis lazuli from Iran and Afghanistan.

Upper Mesopotamia and Northern Syria

Many important Uruk period sites have been found in the Middle Euphrates region. These discoveries led to the idea of an "Uruk expansion."

Habuba Kabira: An Uruk Colony

The most famous site is Habuba Kabira in Syria. It was a walled port city covering about 22 hectares. Studies show it was a planned city. This means it needed a lot of effort to build. The objects found there are just like those from Uruk. These include pottery, cylinder-seals, and early writing tablets. This new city looks like an Urukian colony. About 20 homes were found. They had a special three-part design. The city was left empty at the end of the 4th millennium BC. This happened when the Uruk culture became less powerful.

Habuba Kabira is similar to a nearby site called Jebel Aruda. This city also had homes and a central group of 'temples'. It was also built by people from Uruk. A third possible Urukian colony is Sheikh Hassan. These sites might have been part of a state set up by people from southern Mesopotamia. They were likely built to control important trade routes.

Tell Brak: A Local Powerhouse

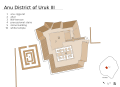

Tell Brak in the Khabur valley was a major city from the 5th millennium BC. It was one of the largest cities in the Uruk period, covering over 110 hectares. Homes and Uruk-style pottery were found there. But the most interesting finds are the religious buildings. The 'Eye Temple' had walls decorated with mosaics made of clay cones. It also had gold, lapis lazuli, and marble decorations. Over two hundred "eye figurines" were found there. These small statues have huge eyes.

Tell Brak also had early writing. It had a numeric tablet and two pictographic tablets. These were different from those in southern Mesopotamia. This shows that Tell Brak had its own writing style. Nearby, Hamoukar also shows signs of Uruk influence. It was another important city in this region during the Uruk period.

Southeast Anatolia: Uruk's Reach

Several sites in the Euphrates valley in southeast Anatolia have been dug up. These are near the Urukian sites of the middle Euphrates. Hacınebi was an important trading spot. Uruk-style pottery and other objects started appearing there around 3800 BC. These items were found alongside local pottery, which was still most common. The excavator thinks people from southern Mesopotamia lived there alongside local people.

Other Urukian sites were found in the Samsat region. For example, at Kurban Höyük, clay cones and Uruk pottery were found in buildings.

Further north, Arslantepe is a remarkable site in eastern Anatolia. In the early 4th millennium BC, it had a building called 'Temple C'. This was replaced by a large complex that seemed to be a regional power center. Late Uruk culture had a clear influence here. This is seen in the many seals found, which are in a southern Mesopotamian style. Around 3000 BC, the site was destroyed. After that, the Kura–Araxes culture from the southern Caucasus became dominant.

The Uruk Expansion: Why Did It Happen?

After sites like Habuba Kabira were found in the 1970s, they were seen as Urukian colonies. These sites had no major settlements before. They were all in the same area on the Middle Euphrates river.

Later, people wondered about the connection between southern Mesopotamia and its neighbors. Uruk culture was found over a huge area. Southern Mesopotamia was clearly the center. This led archaeologists to call it an 'Uruk expansion'.

New digs have focused on sites outside Mesopotamia, the 'periphery'. They want to know how these sites related to Uruk, the 'center'. This has led to many theories.

The main question is what "expansion" really means. Most agree that Uruk had a big cultural influence. But was it a political takeover? Or was it people from Uruk moving to new lands? Maybe they were refugees escaping problems in Uruk.

Another idea is that Uruk wanted to control valuable trade routes. They might have set up trading posts, like the Karum posts used later. These were often run by trading companies, not by the government.

One theory, by Guillermo Algaze, suggests Uruk created colonies for economic reasons. He thought the leaders of southern Mesopotamia wanted raw materials not found in their area. They set up colonies at key points to control trade. He called this "economic imperialism." He believed southern Mesopotamia had an advantage because their land was very productive. This allowed them to grow faster and influence their neighbors. They might even have used military force.

Algaze's theory has been debated. It is hard to prove because we don't know much about Uruk itself, apart from its main buildings. Also, the exact timeline of the Uruk period is still unclear. This makes it hard to date the expansion.

Other theories suggest different reasons for the expansion. Some think it was about farming. Maybe there wasn't enough land in southern Mesopotamia. Or perhaps people moved after environmental or political problems in Uruk. These ideas often explain sites in Syria and Anatolia.

Some experts see the Uruk expansion as a long-term cultural event. They use ideas like 'cultural mixing' and 'imitation'. This means that Uruk provided a model for its neighbors. Each region took what they liked and kept some of their own traditions. This explains why Uruk's influence was different in different places.

For example, in the Levant, Uruk's influence was weak. This was because there were no strong leaders or cities there yet. In Egypt, Uruk's influence was limited to a few special objects. These were seen as fancy or exotic. They were chosen by Egyptian leaders to show their power.

It's important to remember that not all influence went one way. Cities like Tell Brak in Syria grew into urban centers even before Uruk. This suggests that other regions were also developing on their own.

Egypt and Mesopotamia Connections

Egypt-Mesopotamia relations began in the 4th millennium BCE. This was during the Uruk period in Mesopotamia. In Egypt, it was the pre-literate Gerzean culture (around 3500-3200 BCE). We can see Uruk's influence in Egyptian art and in goods that were traded. Some even think writing might have spread from Mesopotamia to Egypt. This created similar features in the early stages of both cultures.

Society and Culture in the Uruk Period

The Uruk period was a time of huge change. Many new ideas and tools appeared. These changed the history of Mesopotamia and the world. During this time, the potter's wheel, writing, cities, and states all appeared. Societies became much more "complex" than before.

Experts study this period as a key step in how societies grew. This process started thousands of years earlier in the Neolithic period. It sped up during the Ubaid period. This is especially true in English-speaking studies. They look at the Uruk period to understand how early states formed. They also study how social classes grew and how long-distance trade increased.

Most research focuses on southern Mesopotamia, the center. It also looks at sites in nearby regions that were clearly part of the Uruk culture. The Late Uruk period is the best known. It was a time of rapid change. This is when the main features of ancient Mesopotamian civilization were set.

New Tools and Economic Changes

The 4th millennium BC saw many new tools. These greatly impacted the people who used them. Some tools, though known before, were used widely for the first time. These inventions led to big economic and social changes. They also helped governments and states grow.

Farming and Animal Raising

Many important farming changes happened during the Uruk period. Some call this the 'Second Agricultural Revolution'. One big change was the invention of the ard. This was a wooden plow pulled by an animal, like a donkey or ox. It made plowing fields much easier. Harvesting also became simpler with the widespread use of terracotta sickles. Irrigation techniques also got better.

These inventions created a new farming landscape in southern Mesopotamia. Fields were long and rectangular, with small irrigation channels. This system, which grew over two thousand years, led to higher crop yields. This meant more food for workers. This also led to more people, cities, and the growth of states.

Animal raising also changed a lot. The wild onager was finally tamed as the donkey. It was the first tamed equid in the region. Donkeys became very important for carrying goods. They could carry twice as much as a human. This helped trade grow over long distances. Animals like sheep, horses, and cattle were raised more for their products. These included wool, fur, hides, and milk. Cattle and donkeys became essential for farm work and transport.

Crafts and Building

Making wool textiles became very important. It slowly replaced linen. This meant more sheep farming. It also changed how land was used. Farmers started letting sheep graze in fields. This helped the soil. The decline of flax (for linen) freed up land for cereals and sesame. Sesame was new to southern Mesopotamia. It was good for making sesame oil.

This led to a big textile industry. Many cylinder-seal prints show this. Wool became a key part of workers' pay, along with barley. This "wool cycle" and "barley cycle" helped the ancient Mesopotamian economy grow. Wool could also be easily traded. This was important because Mesopotamia needed raw materials from other places.

Pottery Making

Pottery making changed a lot with the invention of the potter's wheel. This happened in two steps: first a slow wheel, then a fast one. This made shaping pottery much faster. Pottery kilns also got better. Pottery was often plain, with little decoration.

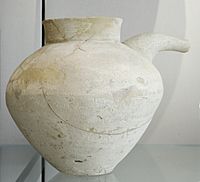

Archaeological sites from this period have huge amounts of pottery. This shows that mass-production was happening. It was for a larger population, especially in cities. Pottery was used for storing food like barley, beer, and dates. This period saw potters who specialized in making large amounts of pottery. This led to special pottery-making areas in cities. The most unique Uruk period pot, the beveled rim bowls, were still made by hand.

-

Uruk period vase. Terracotta, about 3500–2900 BC. From Telloh, ancient city of Girsu. Louvre Museum.

-

Vase. Terracotta with red slip, about 3500–2900 BC. From Telloh, ancient city of Girsu. Louvre Museum.

Metalworking

Metallurgy also grew during this time. But few metal objects have survived. The Ubaid period before it saw the start of the 'copper age'. Most metal objects from the 4th millennium BC are made of copper. Later, people started mixing copper with other metals. For example, copper and arsenic made arsenical bronze. Copper and lead alloys were also used. True tin bronze became common later.

The growth of metalworking meant more long-distance trade. Mesopotamia had to import metal from Iran or Anatolia. This explains why trade grew so much in the 4th millennium BC. Mesopotamian metalworkers used methods that saved raw metal.

Architecture and Building

Building methods also changed a lot in the Uruk period. This is clear from the buildings in the Eanna district of Uruk. They show many new ideas in building size and methods. Builders got better at using molded mud-bricks. They also used stronger terracotta bricks. They started waterproofing bricks with bitumen and using gypsum as mortar.

Clay was not the only building material. Some buildings were made of stone. This included limestone from about 50 km west of Uruk. New decorations appeared, like mosaics made of painted pottery cones. These are special to the Eanna in Uruk. Builders also used new types of bricks. Smaller square bricks (Riemchen) were easy to handle. Large bricks (Patzen) were used for terraces. These were used in big public buildings in Uruk. Smaller bricks allowed for decorative niches and bumps in walls. These became common in Mesopotamian buildings.

The layout of buildings also changed. They no longer used the old three-part design from the Ubaid period. Buildings in the Eanna had complex layouts. They had long halls with pillars inside rectangular buildings. Architects and artists at these sites showed great creativity.

Transportation Methods

One debated question is whether the wheel was invented in the Uruk period. Towards the end of this period, cylinder seals show fewer sleds. Sleds had been the main way to move things on land. Seals started showing the first vehicles that seemed to have wheels. But it's not certain they actually show wheels. However, the wheel spread very quickly. It made it much easier to move larger loads. Wheeled vehicles were definitely in southern Mesopotamia by the early 3rd millennium BC. Their wheels were solid blocks. Spoked wheels came much later.

Taming the donkey was also very important. Donkeys were better than wheels for travel in mountains and over long distances. This was true before spoked wheels were invented. Donkeys allowed for caravans. These would be key for trade in the Near East for thousands of years. But we don't have clear proof of caravans in the Uruk period.

For local travel in southern Mesopotamia, boats made of reeds and wood were vital. Rivers were important for connecting places. Boats could carry much larger loads than land transport.

City-States and Government

The 4th millennium BC saw a new stage in how societies were organized. Political power became stronger and more organized. It was also more visible in art and how cities were built. This led to the development of true states by the end of the period. This growth came with other big changes. The first cities appeared. Also, systems to organize many activities developed. How these changes happened is still debated.

The First States and Their Rules

The Uruk period shows the earliest signs of states in the Near East. The huge buildings are much bigger than before. For example, 'Temple D' in Eanna was about 4600 square meters. The largest Ubaid temple was only 280 square meters. This huge increase shows that leaders could now gather many people and resources.

Tombs also show that some people were much richer than others. This means there was a powerful elite. They wanted special goods to show their status. They got these through trade or by hiring skilled workers. Most experts agree that the Uruk period saw the rise of true states and cities. But some scholars disagree. They think the first true state was later. Still, state-like political structures clearly appeared during the Uruk period.

We are not sure what kind of government existed. There is no proof of a 'proto-empire' centered on Uruk. It was probably more like 'city-states'. These were similar to those in the 3rd millennium BC. Seals from the Jemdet Nasr period show symbols of Sumerian cities like Uruk and Ur. These symbols appearing together might mean the cities had a league or group. Maybe it was for religious reasons, or Uruk was in charge.

Society's political organization clearly changed a lot. We don't know much about the leaders. No palaces or royal tombs have been found for sure. But images on stone slabs and cylinder-seals tell us more. There is an important figure who seems to be in charge. He is a bearded man with a headband and a bell-shaped skirt. He is often shown as a warrior fighting enemies or wild animals. For example, on the 'Stele of the Hunt' from Uruk, he defeats lions. He also leads religious activities. On a vase from Uruk, he leads a procession to a goddess, likely Inanna. Sometimes, he feeds animals. This suggests the idea of a king as a shepherd. He gathers his people, protects them, and makes sure they have what they need. These roles match later Sumerian kings: war-leader, chief priest, and builder. Scholars call this figure the 'Priest-King'. He might be the person called en in Uruk III tablets. This could mean a king-like power existed.

Researchers believe that elites wanted to strengthen their power. They organized people and groups. They also wanted to increase their prestige. This led to new art and ideas about royalty. Elites acted as a link between the gods and humans. They led religious rituals and festivals. This helped them show their role as leaders. The great alabaster vase of Uruk shows this. Many texts also mention goods for rituals. In Mesopotamian belief, humans were made to serve the gods. The gods' favor was needed for society to do well.

The tablets from Late Uruk show that some groups were very important in society and the economy. These groups were likely temples or palaces. Both were powerful later in Mesopotamia's history. Only two names for these groups and their staff have been understood. One was a large authority at Uruk. It had a chief administrator and workers. Another group at Jemdet Nasr had a high priest and administrators. Their scribes wrote documents about managing land and giving out food (barley, wool, oil, beer) to workers, including slaves. They also listed animals. These groups controlled the making of special goods, trade, and public works. They could support many specialized workers. The largest groups had different 'departments' for different activities.

But we don't know if these groups controlled most people. The economy was based on different-sized 'households'. These ranged from large groups to small families. They were always interacting. Some old records found in homes show simple accounting. This suggests smaller economic activity. One study at Abu Salabikh showed that production was shared among different households. The large institutions were at the top.

We don't have one widely accepted theory for why these political structures appeared. Research is influenced by ideas of how societies evolve. It looks at the time before states appeared. States were the result of a long process. This process was not always smooth. It had times of growth and decline. Its roots are in Neolithic societies. It involved a long-term increase in social inequality. This is seen in the huge buildings and rich tombs made by elite groups. These elites became stronger and stronger.

Some theories say states formed to solve problems. These could be managing population growth or getting resources through farming or trade. Others suggest it was to handle conflicts over resources. Other theories focus on individuals seeking power and prestige. It is likely that many of these reasons played a role.

The Rise of Cities

During the Uruk period, some settlements grew very large and dense. They also had huge public buildings. They became so big that we can call them cities. This came with social changes. A new 'urban' society appeared, different from the 'rural' society that grew food. But we don't know much about how these groups related.

Gordon Childe called this the 'urban revolution' in the 1950s. He linked it to the 'Neolithic revolution' and the rise of states. This idea has been debated a lot. Many theories try to explain why cities appeared. Some say cities were religious centers. Others say they were trade hubs. The most common theory, by Robert McCormick Adams, says cities grew because states and their groups appeared. These attracted wealth and people to central places. They also encouraged people to specialize in different jobs. So, the question of why cities started goes back to why states and inequality started.

In the Late Uruk period, Uruk was much bigger than any other city. Its size, huge buildings, and many administrative tools show it was a key power center. It is often called the 'first city'. But it was part of a process that began centuries earlier. The first important proto-urban centers appeared in southwest Iran (Chogha Mish, Susa) and especially in the Jazirah (Tell Brak, Hamoukar). Digs in the Jazirah suggest that cities did not just start in Mesopotamia and spread. For example, Tell Brak grew from villages joining together. This happened without a strong central power. So, early city growth happened in several Near Eastern regions at the same time. More research is needed to understand this better.

Examples of city planning from this period are rare. In southern Mesopotamia, only a small settlement at Abu Salabikh has been dug up. We need to look at Syria, at Habuba Kabira and Jebel Aruda, for better examples. Habuba Kabira was 22 hectares, surrounded by a wall. It had important buildings, main streets, and small alleys. It was clearly a planned city, built from scratch. The planners of this time could create a full city plan. This shows they had a clear idea of what a city should be. But not all areas influenced by Uruk culture had cities. For example, Arslantepe had a large palace but no surrounding city.

Studying houses at Habuba Kabira and Jebel Aruda shows social changes. Habuba Kabira had houses of different sizes. The average was 400 square meters. The largest were over 1000 square meters. The 'temples' at Tell Qanas might have been homes for city leaders. This shows that city centers in the Late Uruk period had clear social differences.

Another sign of early city society is how homes were organized. Houses seemed to turn inward. They had a new floor plan, based on the old three-part design. But they added a reception area and a central open space. Other rooms were around this space. These houses had a private area separate from a public area for guests. In a city, people had more distant relationships than in villages. This led to this separation in homes. So, the old rural house changed for city life. This house style with a central space became common in Mesopotamian cities later.

New Ways of Managing and Writing

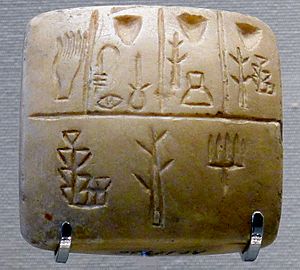

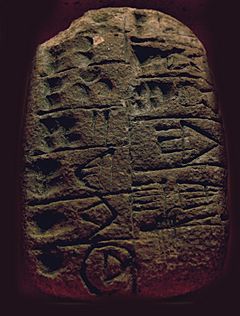

The Uruk period, especially its later part, saw a boom in "symbolic technology." Signs, images, and numbers were used to manage a more complex society. As groups with important economic roles grew, so did tools for administration and accounting. This was a true 'managerial revolution'. A class of scribes developed in the Late Uruk period. They helped create a bureaucracy, but only within the large institutions. Many texts suggest that scribes learned to write management texts. They also used lists of words to learn writing. This helped them manage trading posts. They could record goods coming in and out. This kept exact counts of items in storage. These storage areas were sealed with the administrator's mark. Scribes helped understand and manage the state. They tracked fields, troops, and workers for many years. This meant making lists and creating records of an institution's activities. This was possible because management tools, especially writing, kept getting better.

Seals were used to secure goods or storage areas. They also identified an administrator or merchant. They had been used since the 7th millennium BC. As institutions and trade grew, their use became widespread. During the Uruk period, cylinder seals were invented. These were cylinders with designs that could be rolled over clay. They replaced simple seals. They were used to seal clay envelopes and tablets. They also proved that objects and goods were real. They worked like a signature. Cylinder seals remained a key part of Near Eastern civilization for thousands of years. They were popular because they could show more detailed pictures. They could also tell a story.

The Uruk period also saw accounting tools like tokens and clay envelopes with tokens inside. These were clay balls with a cylinder seal rolled on them. Inside were tokens of different shapes. Each shape might have stood for a number or a type of good. They helped store information for managing groups or trade. They also helped send that information to other places. These tokens might be the same as others found later, whose purpose is still unclear. People think marks were put on the outside of the clay balls. This led to numerical tablets. These were like memory aids before true writing.

The development of writing was a new management tool. It allowed information to be recorded more exactly and for longer. These new ways of managing needed a system of measurement. These varied for different things (animals, workers, wool, grain, tools, pottery, land). Some used a sexagesimal system (base 60), which became common later. Others used a decimal system (base 10) or a mix. This makes understanding the texts harder. Scribes also developed a system for counting time in the Late Uruk period.

Ideas and Beliefs

The changes in society during the Uruk period also affected how people thought and what they believed. This is seen in art. Writing, though linked to managing the state, led to deep intellectual changes. Art showed a society more shaped by political power. Religious practices became grander. We still don't know much about how religious ideas developed.

The Invention of Writing

Writing appeared early in the Middle Uruk period. It then grew more in the Late Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. The first clay tablets with writing were found in Uruk IV (nearly 2000 tablets). Some were also found in Susa II. These first tablets only had numbers. For the Jemdet Nasr period, more evidence comes from more sites. Most are from Uruk III (around 3000 tablets). But they are also from Jemdet Nasr, Tell Uqair, and other places. There were also tablets with proto-Elamite writing in Iran. This was the second writing system in the Near East.

Most texts from this period are about administration. They are found mainly in public places like palaces or temples. But the Uruk texts were found in a trash heap. So, we don't know how they were used. Understanding them is hard because they are so old. The writing is not yet cuneiform. It is linear. German researchers Hans Nissen, Peter Damerow, and Robert Englund made big progress in understanding them. Along with administrative texts, early literary texts were found. These were lexical lists. They were scholarly works that listed signs by themes. For example, a 'List of Professions' listed different types of skilled workers. This shows how many specialized workers there were in Late Uruk.

The reasons and path for writing's origins are debated. The main theory says it came from older accounting practices, like the tokens. In Denise Schmandt-Besserat's idea, tokens were first recorded on clay envelopes, then on clay tablets. This led to the first written signs, which were pictograms. These were drawings of objects. But this is debated because there isn't a clear link between tokens and the pictograms that replaced them.

However, a first step in writing (around 3300–3100 BC) is thought to be based on accounting. This writing system used pictures. It had linear signs carved into clay tablets with a reed pen.

Most Uruk period texts are about management and accounting. So, it makes sense that writing grew from the needs of state groups. These groups did more and more management. Writing allowed them to record complex tasks and create records. Before true writing (around 3400–3200 BC), the system was like a memory aid. It couldn't record full sentences. It only had symbols for real objects, goods, and people. It had many number signs for different measurement systems. It had only a few actions. (Englund calls this the 'numerical tablets' stage).

Signs then started to have more meanings. This allowed for more precise recording of tasks (around 3200–2900 BC). In this period, or later, another type of meaning was recorded using the rebus principle. This means combining pictures to show actions. For example, 'head' + 'water' could mean 'drink'. Homophony (words sounding the same) was also used. For example, 'arrow' and 'life' sounded similar in Sumerian. So, the sign for 'arrow' could mean 'life'. This was hard to draw. So, some ideograms appeared. Following this, phonetic signs were created. These were phonograms, where one sign meant one sound. For example, 'arrow' was pronounced TI in Sumerian. So, the 'arrow' sign could mean the sound [ti]. By the early 3rd millennium BC, the basic rules of Mesopotamian writing were set. Writing could then record grammar and full sentences. But this was not fully used until centuries later.

A newer theory by Jean-Jacques Glassner says writing was more than just a management tool from the start. It was also a way to record ideas and language (Sumerian). From its invention, signs showed not only objects but also ideas and sounds. This theory sees writing as a big change in how the world was understood. From the start, scribes wrote lists of words next to administrative documents. These were scholarly works. They helped scribes explore writing by classifying signs. They also invented new signs and developed the writing system. More generally, they were classifying the world around them. According to Glassner, this means writing's invention was not just about practical needs. Creating such a system needed deep thought about images and the different meanings a sign could have, especially for abstract ideas.

Art in the Uruk Period

The Uruk period saw a big change in art. This came with changes in beliefs. Pottery became simpler after the potter's wheel. Mass production meant less focus on decoration. Painted pottery was less common. The more complex society and powerful elites wanted to show their power in new ways. This gave artists new chances to work in other materials.

Sculpture became very important. This included statues carved in the round and bas-reliefs on stone slabs. It was especially true for cylinder seals, which first appeared in the Middle Uruk period. These seals have been studied a lot. They show the ideas of people from this time. They also spread symbolic messages. Cylinder seals could show more complex scenes than stamp seals. They could be rolled out to create a story.

The art styles of this period were more realistic. Humans were central to this art. This is clear on cylinder seals from Susa. They show the main figure of society, the ruler. But they also show ordinary people doing daily tasks, like farming and weaving. This realism shows a shift. It put humans or the human form in a more important place than ever before. It might be at the end of the Uruk period that gods started to be shown in human form. The Uruk vase likely shows the goddess Inanna in human form. Real and fantasy animals were also common on seals. A popular design was a "cycle" of animals in a continuous line. This used the new possibilities of the cylinder seal.

Sculpture followed the style and themes of seals. Small statues were made of gods or 'priest-kings'. Uruk artists made many amazing works. These are seen in the Sammelfund (hoard) from Eanna level III (Jemdet Nasr period). Bas-reliefs are found on stone slabs like the 'Hunt stele'. The great alabaster vase shows a man giving an offering to a goddess, likely Inanna. These works also highlight a powerful figure. He leads military actions and religious rituals. They are also known for showing realistic details of people. Another amazing work from Uruk III is the Mask of Warka. This is a sculpted female head with realistic features. It was found damaged, but was likely part of a full body.

Religion and Beliefs

It is very hard to understand the religious beliefs of the Late Uruk period. As mentioned, it is hard to find clear religious sites. But in many cases, buildings seem to have been for worship. This is based on how similar they are to later temples. Examples include the White Temple of Uruk and temples at Eridu. Some religious items like altars have been found. It seems gods were worshipped in temples. These buildings were seen as the gods' homes on Earth. Religious staff ('priests') appear in some texts.

The most common goddess in the tablets is Inanna (later Ishtar). She was the great goddess of Uruk. Her temple was in the Eanna area. The other great god of Uruk, Anu (the Sky), might appear in some texts. But the sign for him (a star) can also mean gods in general. These gods received offerings every day. They also received them during festivals. The great vase of Uruk seems to show a procession bringing offerings to Inanna.

The religious beliefs of the 4th millennium BC are debated. Thorkild Jacobsen thought it was a religion focused on gods linked to nature and fertility. But this is just a guess.

Other studies show a shared worship in Sumerian cities during the Jemdet Nasr period. This focused on the goddess Inanna and her temple at Uruk. So, she had a very important role. Gods seemed to be linked to specific cities. This was common in Mesopotamia later. The presence of worship with institutions and bureaucracy, controlled by a royal figure, shows it was an official religion. Sacrifices were seen as a way to keep good relations between humans and gods. This was so the gods would ensure prosperity.

The End of the Uruk Period

Near the end of the 4th millennium BC, smaller settlements in the Uruk heartland were abandoned. At the same time, the city of Uruk itself grew larger. The Eanna area also underwent big changes. Meanwhile, Uruk's influence decreased in northern Mesopotamia, the rest of Syria, and Iran.

Some experts think the end of the Uruk period was caused by the Piora Oscillation. This was a time of cooler temperatures and more rain. Others blame it on new groups of people, like East Semitic tribes, moving into the area.

No matter the cause, Uruk's legacy lived on. This was through the development of cuneiform, which improved on Uruk's early writing. Also, popular myths like the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Great Flood helped preserve its memory.

|

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |