V. Gordon Childe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

V. Gordon Childe

|

|

|---|---|

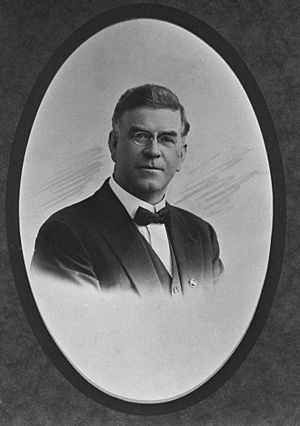

Childe in the 1930s

|

|

| Born |

Vere Gordon Childe

14 April 1892 |

| Died | 19 October 1957 (aged 65) Blackheath, New South Wales, Australia

|

| Alma mater | University of Sydney The Queen's College, Oxford |

| Occupation | |

| Known for |

|

Vere Gordon Childe (born April 14, 1892 – died October 19, 1957) was an Australian archaeologist. He was an expert in the study of European prehistory, which is the time before written records.

He spent most of his life in the United Kingdom. There, he worked as a professor at the University of Edinburgh. Later, he directed the Institute of Archaeology in London. Childe wrote 26 books during his career.

At first, he supported a way of studying the past called culture-historical archaeology. This method focuses on identifying different groups of people based on their tools and art. Later, he became the first person in the Western world to use Marxist archaeology. This approach looks at how society and the economy shaped history.

Childe was born in Sydney, Australia, to an English family. He studied classics at the University of Sydney. Then, he moved to England to study classical archaeology at the University of Oxford. While in England, he became interested in socialism. This is a political idea about sharing wealth and power more equally. He spoke out against World War I, believing it was bad for working people.

He returned to Australia in 1917. Because of his socialist views, he could not get a job at a university. Instead, he worked for the Labor Party. He was a private secretary for politician John Storey. Childe became critical of the Labor Party. He felt they did not stick to their socialist goals. He then joined a radical group called the Industrial Workers of the World.

In 1921, he moved back to London. He became a librarian at the Royal Anthropological Institute. He traveled across Europe to research prehistory. He published his findings in books and papers. He also introduced the idea of an archaeological culture to British archaeologists. This idea suggests that certain groups of artifacts show a distinct cultural group.

From 1927 to 1946, he was a professor at the University of Edinburgh. From 1947 to 1957, he directed the Institute of Archaeology in London. During this time, he led digs at sites in Scotland and Northern Ireland. He focused on the Neolithic people of Orkney. He excavated the settlement of Skara Brae and tombs like Maeshowe. He wrote many books and articles.

In 1934, he helped start The Prehistoric Society. He became its first president. Childe remained a socialist. He used Marxism to understand archaeological data. He visited the Soviet Union several times. He supported their socialist ideas, but later questioned their foreign policy. Because of his beliefs, he was not allowed to enter the United States. After retiring, he returned to Australia. He died in the Blue Mountains.

Childe was one of the most famous archaeologists of his time. He was known as the "great synthesizer." This means he brought together research from different areas. He connected the prehistory of the Near East and Europe. He also stressed the importance of big changes in human society. These included the Neolithic Revolution (when farming began) and the Urban Revolution (when cities grew). These ideas came from his Marxist beliefs about how societies develop. Many of his specific ideas have changed over time. But he is still highly respected by archaeologists today.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in Australia

Gordon Childe was born in Sydney, Australia, on April 14, 1892. He was the only child of Stephen Henry Childe and Harriet Eliza Childe. His parents were from England and were middle-class. His father was an Anglican priest.

Gordon grew up with five half-siblings. They lived in a large house called the Chalet Fontenelle. This house was in Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains. His father was a minister but was not very popular.

Gordon was often sick as a child. He was taught at home for several years. Later, he went to a private school in North Sydney. In 1907, he started at Sydney Church of England Grammar School. He did well in subjects like ancient history, French, and Latin. But he was bullied because of how he looked.

In 1910, his mother died. His father remarried soon after. Gordon's relationship with his father was difficult. They disagreed about religion and politics. His father was a strong Christian and conservative. Gordon became an atheist and a socialist.

Studying at University

In 1911, Childe began studying classics at the University of Sydney. He learned about classical archaeology by reading works from archaeologists like Heinrich Schliemann. At university, he joined the debating society. He argued that "socialism is desirable." He became very interested in socialism. He read books by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He also studied the philosopher G. W. F. Hegel. Hegel's ideas greatly influenced Marxist theory.

He became good friends with Herbert Vere Evatt, who later became a judge and politician. Childe finished his studies in 1913. He graduated with many honors and prizes.

He wanted to continue his education. He won a scholarship that allowed him to study in England. In August 1914, he sailed to Britain. This was just after World War I began. At Queen's College, part of the University of Oxford, he studied classical archaeology. His supervisor was Arthur Evans, a famous archaeologist.

In 1915, he published his first academic paper. It was about ancient pottery. The next year, he wrote his thesis. It showed his interest in combining language studies and archaeology.

At Oxford, he became active in the socialist movement. This upset the university authorities. He joined the Oxford University Socialist Society. His best friend and flatmate was Rajani Palme Dutt, a strong socialist. They often discussed classical history late at night.

During World War I, many socialists refused to fight. They believed the war was for the rich, not the working class. Dutt was put in prison for refusing to fight. Childe campaigned for his release and for other socialists. Childe never had to join the army. This was likely because of his poor health and eyesight. The government watched him because of his anti-war views. His mail was even checked.

Early Career and Books

Working in Australia

Childe returned to Australia in August 1917. Because he was a known socialist, security services watched him. In 1918, he became a tutor at St Andrew's College, Sydney University. He joined Sydney's socialist movement. He spoke at a peace conference that opposed conscription (forced military service).

The college principal found out about his speech. Childe was forced to resign. Other staff members helped him find work as a tutor in ancient history. But the university chancellor feared he would teach socialism. So, Childe was fired again. Many people saw this as a violation of his civil rights. Politicians even brought it up in the Australian Parliament.

In October 1918, Childe moved to Maryborough, Queensland. He taught Latin at a boys' school. His political views became known there too. Local conservative groups campaigned against him. He soon resigned from that job.

Childe realized he would not have an academic career in Australia. So, he looked for work within the socialist movement. In August 1919, he became a private secretary and speechwriter for John Storey. Storey was a leading member of the Labor Party. Storey became the state premier in 1920.

Working for the Labor Party gave Childe insight into its operations. The more he was involved, the more he criticized the party. He believed they gave up their socialist ideals once they gained power. He joined the radical Industrial Workers of the World, which was banned in Australia at the time. In 1921, Storey sent Childe to London. Storey died in December, and a new government took over in Australia. Childe's job was ended in early 1922.

Moving to London and First Books

Childe could not find an academic job in Australia. So, he stayed in Britain. He rented a room in Bloomsbury, Central London. He spent a lot of time studying at the British Museum. He was also active in London's socialist movement. He became friends with members of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

He gained a good reputation as a prehistorian. He was invited to other parts of Europe to study ancient artifacts. In 1922, he traveled to Vienna to study pottery from the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture. He published his findings. He also visited museums in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. He shared what he learned with British archaeologists.

After returning to London, Childe worked as a private secretary for three Members of Parliament. He also translated books for publishers. Sometimes, he lectured on prehistory at the London School of Economics.

In 1923, his first book, How Labour Governs, was published. It looked at the Australian Labor Party. The book showed Childe's disappointment with the party. He argued that politicians abandoned their socialist ideas once elected. This book was important because the British Labour Party was becoming a major force in British politics.

In 1923, he visited museums in Switzerland to study ancient collections. That year, he joined the Royal Anthropological Institute. In 1925, he became the institute's librarian. This job helped him connect with scholars across Europe. He became well known in Britain's small archaeological community. He became good friends with O. G. S. Crawford, an archaeological officer.

In 1925, Childe published his second book, The Dawn of European Civilisation. In it, he brought together information about European prehistory. This was an important book. At the time, few archaeologists looked at the big picture across the continent. The book also introduced the idea of an archaeological culture to Britain. This helped develop culture-historical archaeology. Childe later said the book aimed to create a "preliterate substitute for conventional history."

In 1926, he published The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins. This book explored the idea that civilization spread into Europe from the Near East. It suggested this happened through a group called the Aryans. Later, the German Nazi Party used the term "Aryan" in a racist way. After that, Childe avoided mentioning this book. In these early works, Childe believed in a moderate form of diffusionism. This is the idea that cultural developments spread from one place to another.

Later Career and Impact

Professor in Edinburgh

In 1927, the University of Edinburgh offered Childe a new job. He became the Abercromby Professor of Archaeology. He moved to Edinburgh in September 1927. He was 35 years old. He was the only professor teaching prehistory in Scotland. Some Scottish archaeologists did not like him. They saw him as an outsider. But he made friends in Edinburgh. These included other archaeologists and scientists.

At Edinburgh University, Childe focused on research. He was kind to his students. But he found it hard to speak to large groups. He often took his keen students on digs. He also invited guest speakers. He was one of the first to use experimental archaeology. In 1937, he used this method to study ancient forts.

Childe often visited London to see friends. These included Stuart Piggott and Grahame Clark, who were also important archaeologists. The three of them helped turn a local archaeological group into the national Prehistoric Society in 1935. Childe was elected its first president. The group grew quickly.

Childe traveled often in Europe. He learned several European languages. In 1935, he visited the Soviet Union for the first time. He was impressed by the socialist state. He was especially interested in how archaeology was used in Soviet society. He became a strong supporter of the Soviet Union. He read their communist newspaper. But he also criticized some Soviet policies. He strongly opposed fascism in Europe. He was angry that the Nazis used archaeology to promote their racist ideas. He supported Britain fighting the fascists in World War II.

He also criticized the capitalist governments of the UK and US. He called the US "loathsome fascist hyenas." But he still visited the US. In 1936, he spoke at Harvard University. He received an honorary degree there. He returned in 1939 to give more lectures.

Archaeological Digs

Childe's university job meant he had to lead archaeological digs. He did not enjoy this. He felt he was not good at it. His students agreed. But they recognized his skill in understanding what the finds meant. Unlike many others, he was careful to write up and publish his findings. He published reports almost every year. He also made sure to thank every person who helped on the dig.

His most famous dig was from 1928 to 1930 at Skara Brae in the Orkney Islands. He uncovered a very well-preserved Neolithic village. In 1931, he published a book about the dig called Skara Brae. He made one mistake in his interpretation. He wrongly thought the site was from the Iron Age. Childe got along well with the local people during the dig. They saw him as a true professor because of his unique look and habits.

In 1932, Childe worked with C. Daryll Forde. They excavated two Iron Age hillforts in Scotland. In 1935, he dug at a fort in Northern Ireland. He also excavated two vitrified Iron Age forts in Scotland. These were at Finavon (1933–34) and Rahoy (1936–37). In 1938, he oversaw digs at the Neolithic settlement of Rinyo. This work stopped during World War II but started again in 1946.

Important Books

Childe kept writing and publishing archaeology books. He started with books that built on The Dawn of European Civilisation. These books brought together information from across Europe. His first was The Most Ancient Near East (1928). It gathered information from Mesopotamia and India. This helped explain how farming spread into Europe.

Next was The Danube in Prehistory (1929). This book looked at archaeology along the Danube river. Childe believed new technologies traveled westward along the Danube. In this book, Childe gave a clear definition of an archaeological culture. This changed how British archaeology was studied.

Childe's next book, The Bronze Age (1930), was about the Bronze Age in Europe. It showed his growing use of Marxist theory. He used it to understand how society worked and changed. He believed metal was the first important trade item. He thought metalworkers were full-time professionals.

In 1933, Childe traveled to Asia. He visited Iraq and India. He felt much of what he wrote in The Most Ancient Near East was out of date. So, he wrote New Light on the Most Ancient Near East (1935). In this book, he applied his Marxist ideas about the economy.

After publishing Prehistory of Scotland (1935), Childe wrote one of his most important books. It was called Man Makes Himself (1936). Influenced by Marxist ideas, Childe argued that human society progressed through big changes. He called these "revolutions." These included the Neolithic Revolution. This was when hunter-gatherers started farming and settling down. Then came the Urban Revolution. This was when small towns grew into the first cities. He also included the Industrial Revolution in more recent times.

During World War II, Childe could not travel. He focused on writing Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles (1940). He was worried about the war's outcome. He thought European civilization was heading for a "Dark Age." With this in mind, he wrote a follow-up to Man Makes Himself. It was called What Happened in History (1942). This book covered human history from the Stone Age to the fall of the Roman Empire. He chose to publish it with Penguin Books. This was because they could sell it cheaply. He believed this was important for sharing knowledge with "the masses." He then wrote two shorter books: Progress and Archaeology (1944) and The Story of Tools (1944). The latter was a Marxist text for young communists.

Director in London

In 1946, Childe left Edinburgh. He became the director and professor of European prehistory at the Institute of Archaeology (IOA) in London. He was eager to return to London. He lived in the Isokon building in Hampstead.

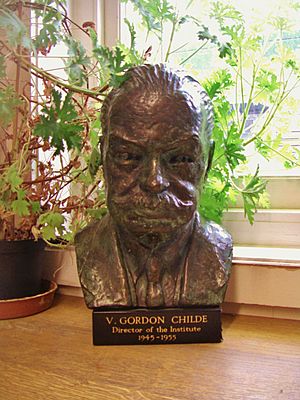

The IOA was founded in 1937. It relied mostly on volunteer teachers until 1946. Childe's relationship with the conservative archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler was difficult. They had very different personalities. Wheeler was outgoing and good at managing. Childe was not good at managing. But he was popular with students. They saw him as a kind and unusual person. They even had a bust of him made.

His lectures were not considered good. He often mumbled. But he was better at tutorials and seminars. There, he spent more time talking with students. As Director, Childe did not have to lead digs. But he did work on two Neolithic burial tombs in Orkney. These were Quoyness (1951) and Maes Howe (1954–55).

In 1949, he and Crawford resigned from the Society of Antiquaries. They did this to protest the choice of president. They believed Wheeler was a better choice. Childe joined the editorial board of a journal called Past & Present. It was started by Marxist historians in 1952. He also wrote articles for his friend Rajani Palme Dutt's socialist journal. But they disagreed about the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Palme Dutt supported the Soviet Union's actions. Childe, like many Western socialists, strongly opposed it. This event made Childe lose faith in the Soviet leadership. But he still believed in socialism and Marxism. He loved the Soviet Union and visited many times.

In April 1956, Childe received the Gold Medal of the Society of Antiquaries. This was for his work in archaeology. He was invited to lecture in the United States many times. But the U.S. State Department stopped him from entering the country. This was because of his Marxist beliefs.

While at the institute, Childe kept writing books. History (1947) promoted a Marxist view of the past. It said that prehistory and written history should be seen together. Prehistoric Migrations (1950) showed his ideas on moderate diffusionism. In 1946, he also wrote a paper called "Archaeology and Anthropology." It argued that archaeology and anthropology should be used together. This idea became widely accepted later.

Retirement and Death

In mid-1956, Childe retired early from his role as IOA director. European archaeology had grown quickly in the 1950s. This made it harder to combine all the research, which Childe was known for. The institute was also moving to a new location. Childe wanted his successor to have a fresh start.

To honor his work, a special edition of the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society was published. It included contributions from friends and colleagues worldwide. This touched Childe deeply. When he retired, he told friends he planned to return to Australia. He was afraid of getting old and sick. He also suspected he had cancer.

Childe gave most of his books and his estate to the institute. After a holiday in Gibraltar and Spain in February 1957, he sailed to Australia. He arrived in Sydney on his 65th birthday. The University of Sydney, which had once refused to hire him, gave him an honorary degree.

He traveled around Australia for six months. He visited family and old friends. But he was not impressed with Australian society. He thought it was too traditional and not well-educated. He found Australian prehistory interesting for research. He gave lectures to archaeological and socialist groups. He also spoke on Australian radio. He criticized academic racism towards Indigenous Australians.

On October 19, 1957, Childe went to Govett's Leap in Blackheath. This was an area in the Blue Mountains where he grew up. He died after falling from the cliff. A coroner ruled his death as accidental. His remains were cremated. After his death, many tributes and memorials were made by archaeologists. They called him Europe's "greatest prehistorian and a wonderful human being."

Archaeological Ideas

Childe's ideas were always changing and unique. He combined Marxism, diffusionism, and functionalism in his archaeological theories. He did not like the evolutionary archaeology that was popular in the 1800s. He felt it focused too much on artifacts and not enough on the people who made them. Like many archaeologists of his time, Childe did not think humans were naturally inventive. So, he often saw social change as things spreading from one place to another, rather than developing independently.

Most archaeologists in Childe's time used the three-age system. This system divided prehistory into the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age. Childe used this system. But he also pointed out that many societies still used Stone Age technology. He found it useful for understanding how societies developed. He used technology to divide prehistory into three ages. But he used economic ideas to divide the Stone Age into the Palaeolithic and Neolithic. He did not find the Mesolithic period useful. He also used the terms "savagery," "barbarism," and "civilization" to describe past societies. These terms were used by Engels.

Culture-Historical Archaeology

Early in his career, Childe was a big supporter of the culture-historical approach. He was seen as one of its founders. This approach uses the idea of "culture" from anthropology. It was a major change in archaeology. It allowed archaeologists to look at the past in terms of space, not just time. Childe got the idea of "culture" from a German archaeologist named Gustaf Kossinna.

Childe used this approach in his early books. These included The Dawn of European Civilisation (1925) and The Aryans (1926). But he did not define "culture" in these books. Later, in The Danube in Prehistory (1929), he gave a clear archaeological definition. He said a "culture" was a group of "regularly associated traits." These were things like "pots, tools, ornaments, burial rites, house forms." They would be found together in a certain area. He said that a "culture" was like an archaeological "people."

Childe's use of "people" was not about race. He saw a "people" as a social group, not a biological race. He was against linking archaeological cultures to biological races. Many nationalists in Europe were doing this at the time. He strongly criticized the Nazi use of archaeology. He argued that Jewish people were a social group, not a distinct race. In 1935, he suggested that culture worked like a "living organism." He stressed how material culture helps people adapt. In this, he was influenced by functionalism in anthropology. Childe knew that archaeologists chose what material things to use to define "cultures." This idea was later used by other archaeologists.

Later in his career, Childe grew tired of culture-historical archaeology. By the late 1940s, he questioned if "culture" was a useful idea in archaeology. He wondered if a certain group of artifacts really showed a social group with shared traits, like a language. In the 1950s, he compared culture-historical archaeology to the traditional way historians studied politics and war.

Marxist Archaeology

"To me Marxism means effectively a way of approach to and a methodological device for the interpretation of historical and archaeological material and I accept it because and in so far as it works. To the average communist and anti-communist alike ... Marxism means a set of dogmas—the words of the master from which as among mediaeval schoolmen, one must deduce truths which the scientist hopes to infer from experiment and observation."

Childe is known as a Marxist archaeologist. He was the first archaeologist in the West to use Marxist ideas in his work. Marxist archaeology started in the Soviet Union in 1929. An archaeologist named Vladislav I. Ravdonikas said that archaeology should be pro-socialist and Marxist.

Many archaeologists have been influenced by Marxism. Marxism is a materialist philosophy. It says that material things are more important than ideas. It also says that social conditions come from existing material conditions, like how things are produced. So, a Marxist view looks at the social reasons behind technological changes. Marxism also says that scholars have their own beliefs and class loyalties. It argues that thinkers cannot separate their ideas from political actions. Sally Green, a biographer, said Childe used Marxist ideas because they helped him understand the past. They offered a way to analyze culture based on economy, society, and ideas.

Childe said he used Marxist ideas because they "worked." He criticized other Marxists for treating the theory as strict rules. Childe's Marxism was often different from others. He read the original texts of Marx and Engels. He also chose which parts of their writings to use. Scholars called his Marxism "an individual interpretation" and "creative."

Childe knew that his connection to Marxism could be risky during the Cold War. So, he did not often mention Marx directly in his archaeological writings. There is a difference in his later books. Some are clearly Marxist, while others show less obvious Marxist ideas. Many British archaeologists did not take his Marxism seriously. They thought he did it to shock people.

Childe was influenced by Soviet archaeology. But he also criticized it. He did not like how the Soviet government encouraged archaeologists to decide their conclusions before looking at the data. He also criticized their sloppy approach to classifying artifacts. Childe was a moderate diffusionist. He strongly criticized a Soviet archaeological trend that rejected diffusionism. He believed it was not "un-Marxian" to understand how plants, animals, and ideas spread. Childe did not publicly share these criticisms. Perhaps he did not want to offend communist friends. Instead, he publicly praised the Soviet system of archaeology. He said it was better than Britain's because it encouraged teamwork. He visited the Soviet Union several times. But shortly before his death, he wrote a letter saying he was "extremely disappointed" that they had fallen behind Western Europe.

Other Marxists argued that Childe's work was not truly Marxist. They said he did not consider class struggle as a cause of social change. This is a main idea in Marxism. Childe did not use class struggle in his archaeological work. But he did believe that historians and archaeologists often saw the past through their own class interests. He argued that most of his peers wrote studies with a hidden capitalist agenda. Childe also differed from traditional Marxism by not using dialectics in his methods. He also said that Marxism could not predict the future of human society. Unlike other Marxists, he did not think humanity's progress to pure communism was certain. He thought society could stop developing or even die out.

Neolithic and Urban Revolutions

Childe, influenced by Marxism, argued that society changed greatly in short periods. He used the Industrial Revolution as a modern example. This idea was not in his earliest work. In books like The Dawn of European Civilisation, he talked about societal change as a "transition." In the early 1930s, he started using the term "revolution" to describe social change. At this time, the word "revolution" had Marxist connections because of Russia's October Revolution of 1917.

Childe introduced his ideas about "revolutions" in a speech in 1935. He said that a "Neolithic Revolution" started the Neolithic era. He also said other revolutions marked the start of the Bronze and Iron Ages. The next year, in Man Makes Himself, he combined the Bronze and Iron Age Revolutions into one "Urban Revolution." This was similar to the idea of "civilization."

For Childe, the Neolithic Revolution was a time of huge change. Humans, who were hunter-gatherers, started growing plants and raising animals for food. This gave them more control over food and led to population growth. He believed the Urban Revolution was mainly caused by the development of bronze metalworking. In a 1950 paper, he listed ten features of the oldest cities. These included being larger than earlier settlements, having full-time craftspeople, and having writing. Childe thought the Urban Revolution also had a negative side. It led to more social classes and the oppression of many people by a powerful few. Not all archaeologists agreed with Childe's idea of "revolutions." Many thought the term was misleading. They believed agricultural and urban development were gradual changes.

Influence on Archaeology Today

Childe's work influenced two major archaeological movements that appeared after his death. These were processualism and post-processualism. Processualism started in the late 1950s. It said archaeology should be part of anthropology. It tried to find universal laws about society. It also believed archaeology could find objective information about the past. Post-processualism began in the late 1970s. It disagreed with processualism. It said that archaeological interpretation is always subjective.

The processual archaeologist Colin Renfrew called Childe "one of the fathers of processual thought." This was because of his focus on economic and social themes in prehistory. Bruce Trigger, another scholar, said Childe's work predicted processual thought. This was because he stressed change in society and had a materialist view of the past. These ideas came from his Marxism. But most American processualists ignored Childe's work. They saw him as someone who focused on specific details, not general laws. Childe did not believe such general laws existed. He thought behavior was shaped by social and economic factors.

Peter Ucko, a later director of the Institute of Archaeology, said Childe accepted that archaeological interpretation was subjective. This was different from processualists who insisted on objective interpretation. Because of this, Trigger called Childe a "prototypical post-processual archaeologist."

Personal Life and Interests

Childe was a private person. He had many friends of both sexes. But he was often "awkward and uncouth." Despite this, he enjoyed spending time with his students. He often invited them to dinner. He was shy and kept his feelings hidden. Some people thought his personality traits might be like Asperger syndrome.

Childe believed that studying the past could help people in the present and future. He was known for his radical left-wing views. He was a socialist from his university days. He served on committees for several left-wing groups. But he avoided getting involved in Marxist arguments within the Communist Party. Most of his political views are known only from his private letters.

Renfrew noted that Childe was open-minded on social issues. He hated racism. But some of his early writings had racist ideas. For example, he suggested that Nordic peoples were "superior." Childe later rejected these ideas.

Childe was an atheist. He criticized religion. He saw it as a way to control people. In his book History (1947), he wrote that "magic is a way of making people believe they are going to get what they want, whereas religion is a system for persuading them that they ought to want what they get." But he still thought Christianity was better than what he called "primitive religion."

Childe loved driving cars. He enjoyed the "feeling of power" they gave him. He often told a story about speeding down Piccadilly in London late at night. He was pulled over by a policeman. He also loved playing practical jokes. He once gave a lecture where he joked that a Neolithic monument was built by a rich chieftain trying to copy another monument. Some people in the audience did not realize he was joking. He could speak several European languages. He taught himself these languages when he traveled.

Childe's other hobbies included walking in the British hills. He also enjoyed classical music concerts. He liked playing the card game contract bridge. He loved poetry. His favorite poet was John Keats. He was not very interested in reading novels. But his favorite was D. H. Lawrence's Kangaroo. This book reflected many of Childe's own feelings about Australia. He enjoyed good food and drink. He often went to restaurants.

Childe was known for his old, worn-out clothes. He always wore his wide-brimmed black hat. He also wore a tie, usually red, to show his socialist beliefs. He often wore a black raincoat like a cape. In summer, he sometimes wore shorts with socks and large boots.

Legacy and Influence

After his death, Childe was praised by his colleague Stuart Piggott. Piggott called him "the greatest prehistorian in Britain and probably the world." Archaeologist Randall H. McGuire later said he was "probably the best known and most cited archaeologist of the twentieth century." Barbara McNairn called him "one of the most outstanding and influential figures in the discipline." Andrew Sherratt said Childe held "a crucial position in the history" of archaeology.

Sherratt also noted that "Childe's output, by any standard, was massive." Childe published over twenty books and about 240 scholarly articles. Brian Fagan, an archaeologist, said his books were "simple, well-written narratives." They became "archaeological canon" from the 1930s to the early 1960s. By 1956, he was the most translated Australian author in history. His books were published in many languages.

Childe was known as "the Great Synthesizer." He is respected for bringing together the prehistory of Europe and the Near East. At that time, most archaeologists focused on small, local sites. Since his death, his ideas have been changed a lot. This is because of new methods like radiocarbon dating. Many of his ideas about Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe have been found to be wrong. Childe himself believed his main contribution was his way of interpreting findings. This idea is supported by other scholars.

Sherratt said: "What is of lasting value in his interpretations is the more detailed level of writing, concerned with the recognition of patterns in the material he described. It is these patterns which survive as classic problems of European prehistory, even when his explanations of them are recognised as inappropriate." Childe's theoretical work was largely ignored during his lifetime. It remained forgotten for decades after his death. But it became popular again in the late 1990s and early 2000s. His work remained well known in Latin America. There, Marxism was a main idea among archaeologists throughout the late 20th century.

Childe's work was not well understood in the United States. His work on European prehistory was not widely known there. So, in the US, he wrongly gained a reputation as a Near Eastern expert. He was also seen as a founder of neo-evolutionism, along with Julian Steward and Leslie White. But his approach was "more subtle and nuanced" than theirs. Steward often wrongly described Childe as a unilinear evolutionist. He may have done this to make his own "multilinear" evolutionary approach seem different from Marx and Engels.

Despite this, Childe had a small group of American archaeologists and anthropologists who followed him in the 1940s. They wanted to bring materialist and Marxist ideas back into their research. His name was also mentioned in the 2008 movie Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.

Academic Events and Publications

After Childe's death, many articles were published about his impact on archaeology. In 1980, Bruce Trigger's book Gordon Childe: Revolutions in Archaeology came out. It looked at the influences on Childe's archaeological ideas. The same year, Barbara McNairn's The Method and Theory of V. Gordon Childe was published. It examined his methods and theories. The next year, Sally Green published Prehistorian: A Biography of V. Gordon Childe. She called him "the most eminent and influential scholar of European prehistory in the twentieth century." Peter Gathercole thought these works were "extremely important."

In July 1986, a meeting about Childe's work was held in Mexico City. It marked 50 years since Man Makes Himself was published. In September 1990, a conference for Childe's 100th birthday was held in Brisbane. It looked at both his scholarly and socialist work. In May 1992, another conference for his centenary was held in London. It was at the UCL Institute of Archaeology. The talks from this conference were published in a 1994 book. It was called The Archaeology of V. Gordon Childe: Contemporary Perspectives. The book aimed to show how dynamic Childe's ideas were. It also showed the depth of his knowledge and how relevant his work still is. In 1995, another collection of conference papers was published. It was called Childe and Australia: Archaeology, Politics and Ideas. More papers about Childe appeared in later years. They looked at things like his personal letters and where he was buried.

Selected Publications

| Title | Year | Publisher |

|---|---|---|

| The Most Ancient East | 1922, 1928 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| How Labour Governs: A Study of Workers' Representation in Australia | 1923 | The Labour Publishing Company (London) |

| The Dawn of European Civilization | 1925 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| The Aryans: A Study of Indo-European Origins | 1926 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| The Most Ancient East: The Oriental Prelude to European Prehistory | 1929 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| The Danube in Prehistory | 1929 | Oxford University Press (Oxford) |

| The Bronze Age | 1930 | Cambridge University Press (Cambridge) |

| Skara Brae: A Pictish Village in Orkney | 1931 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| The Forest Cultures of Northern Europe: A Study in Evolution and Diffusion | 1931 | Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (London) |

| The Continental Affinities of British Neolithic Pottery | 1932 | Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (London) |

| Skara Brae Orkney. Official Guide | 1933 Second Edition 1950 | His Majesty's Stationery Office (Edinburgh) |

| New Light on the Most Ancient East: The Oriental Prelude to European Prehistory | 1935 | Kegal Paul (London) |

| The Prehistory of Scotland | 1935 | Kegan Paul (London) |

| Man Makes Himself | 1936, slightly revised 1941, 1951 | Watts (London) |

| Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles | 1940, second edition 1947 | Chambers (London) |

| What Happened in History | 1942 | Penguin Books (Harmondsworth) |

| The Story of Tools | 1944 | Cobbett (London) |

| Progress and Archaeology | 1944 | Watts (London) |

| History | 1947 | Cobbett (London) |

| Social Worlds of Knowledge | 1949 | Oxford University Press (London) |

| Prehistoric Migrations in Europe | 1950 | Aschehaug (Oslo) |

| Magic, Craftsmanship and Science | 1950 | Liverpool University Press (Liverpool) |

| Social Evolution | 1951 | Schuman (New York) |

| Illustrated Guide to Ancient Monuments: Vol. VI Scotland | 1952 | Her Majesty's Stationery Office (London) |

| Society and Knowledge: The Growth of Human Traditions | 1956 | Harper (New York) |

| Piecing Together the Past: The Interpretation of Archeological Data | 1956 | Routledge and Kegan Paul (London) |

| A Short Introduction to Archaeology | 1956 | Muller (London) |

| The Prehistory of European Society | 1958 | Penguin (Harmondsworth) |

Images for kids

-

Neolithic dwellings at Skara Brae in Orkney, the site excavated by Childe 1927–30

-

The Neolithic passage tomb of Maes Howe on Mainland, Orkney, excavated by Childe 1954–55

-

The bronze bust of Childe by Marjorie Maitland Howard has been kept in the library of the Institute of Archaeology since 1958. Childe thought it made him look like a Neanderthal.

See also

In Spanish: Vere Gordon Childe para niños

In Spanish: Vere Gordon Childe para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |