Mortimer Wheeler facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir Mortimer Wheeler

|

|

|---|---|

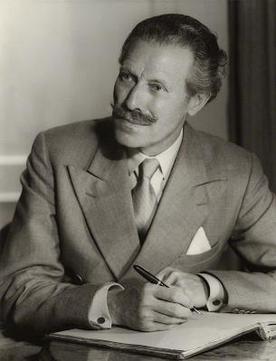

Mortimer Wheeler in 1956

|

|

| Born |

Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler

10 September 1890 Glasgow, Scotland

|

| Died | 22 July 1976 (aged 85) Leatherhead, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University College London |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | Michael Mortimer Wheeler |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Archaeology |

| Influences | Augustus Pitt-Rivers |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1914–1921 1939–1948 |

| Rank | Brigadier |

| Unit | Royal Artillery |

| Commands held | 42nd Mobile Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Military Cross Territorial Decoration |

Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler (1890–1976) was a famous British archaeologist and a brave officer in the British Army. He held many important jobs, like being the Director of the National Museum of Wales and the London Museum. He also led the Archaeological Survey of India and started the Institute of Archaeology in London. He wrote many books about archaeology, helping to share its wonders with everyone.

Born in Glasgow, Scotland, Wheeler grew up mostly in Yorkshire before moving to London as a teenager. He studied classics at University College London (UCL). After university, he became a professional archaeologist, focusing on the Romano-British period. During World War I, he joined the Royal Artillery and fought on the Western Front. He became a major and earned the Military Cross for his bravery.

After the war, he got his doctorate from UCL. He then worked at the National Museum of Wales, where he led important excavations at Roman forts like Segontium and Isca Augusta. He believed that archaeology should be very scientific and organized. He developed a special way of digging, sometimes called the "Wheeler method". In 1926, he became the Keeper of the London Museum, where he improved its collections and got more funding.

In 1934, he founded the Institute of Archaeology. He led digs at Roman sites like Verulamium and the Iron Age hill fort of Maiden Castle. During World War II, he rejoined the army and became a brigadier. He served in the North African Campaign and the Allied invasion of Italy. In 1944, he became the Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India. There, he led excavations at ancient sites like Harappa and Arikamedu.

After returning to Britain in 1948, he taught at the Institute of Archaeology and advised the Pakistani government on archaeology. Later in his life, he became very well-known through his popular books, lectures, and TV appearances, especially on the BBC show Animal, Vegetable, Mineral?. He helped many people learn about and love archaeology. He also helped raise a lot of money for archaeological projects.

Mortimer Wheeler is remembered as one of the most important British archaeologists of the 20th century. He made archaeology more popular and improved how digs were done. He also played a big role in developing archaeology in South Asia.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Growing Up: 1890–1907

Mortimer Wheeler was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on September 10, 1890. He was the first child of Robert Mortimer Wheeler, a journalist, and Emily Wheeler.

When Mortimer was four, his family moved to Saltaire in Yorkshire, England. He loved the moors around Saltaire and became very interested in archaeology. He wrote about finding ancient cup-marked stones and digging into old burial mounds called barrows. His mother taught him and his sister at home when they were young. Mortimer was very close to his father, who encouraged his love for nature, art, and reading.

In 1899, Mortimer started at Bradford Grammar School. In 1905, his family moved to London. When he was 15, he spent time exploring London's museums, like the National Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum, instead of going to a regular school.

University and Early Work: 1907–1914

In 1907, Wheeler won a scholarship to study classical studies at University College London (UCL). He traveled to the university every day from his family home. He even tried studying at UCL's Slade School of Fine Art because he was interested in art, but he soon returned to his classical studies. He earned his Master of Arts degree in 1912.

During his time at UCL, he met Tessa Verney, who was also a student there. They later got married. Wheeler became very interested in archaeology during his studies. In 1913, he joined an excavation at Viroconium Cornoviorum, a Roman-British town.

In 1913, Wheeler got a job as a junior investigator for the English Royal Commission on Historical Monuments. He helped record old buildings and Roman remains in Essex. In the summer of 1914, he married Tessa, and they moved into his parents' home.

Military Service in World War I

Fighting on the Front: 1914–1918

When World War I began in 1914, Wheeler joined the armed forces. He really enjoyed being a soldier. On November 9, 1914, he became a temporary second lieutenant in the University of London Officer Training Corps, teaching artillery. In January 1915, his son, Michael, was born.

In May 1915, Wheeler moved to the Royal Field Artillery. He quickly rose through the ranks, becoming a temporary captain and then an acting major. In October 1917, his unit was sent to Belgium to fight in the Battle of Passchendaele on the Western Front. He led an artillery battery, replacing a major who had been injured.

After the battle, his unit moved to Italy to help Italian troops. In March 1918, they returned to the Western Front in France. Wheeler was involved in artillery fire for several months. In August, the British forces went on the attack. On August 24, he bravely led a team to capture two German field guns while under heavy fire. For this action, he was awarded the Military Cross.

He continued fighting until Germany surrendered in November 1918. He stayed in Germany for several months before returning to London in July 1919. He was officially discharged from service in September 1921, keeping the rank of major.

Archaeological Career

National Museum of Wales: 1919–1926

After the war, Wheeler returned to London and continued working for the Royal Commission. He wrote his first academic paper about Colchester's Roman Balkerne Gate. He also earned his Doctor of Letters degree. He wanted a more challenging job than what the commission offered.

In August 1920, he became the Keeper of Archaeology at the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff. He also lectured at the university there. The museum was in a difficult state, with a new building unfinished. Wheeler traveled around Wales, giving talks about archaeology to local groups.

He was eager to start digging. In July 1921, he began a six-week excavation at the Roman fort of Segontium. His wife, Tessa, helped him. Wheeler believed in careful planning for archaeological digs, calling it "controlled discovery". He also made sure to publish his findings quickly. He wanted to train new archaeologists, and many students worked with him at Segontium.

From 1924 to 1925, Wheeler led excavations at the Roman fort of Y Gaer near Brecon. He was visited by famous Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie, whom he greatly admired for his strong archaeological methods. Wheeler then started digging at Isca Augusta, a Roman site in Caerleon, focusing on the Roman amphitheater. He worked to get press attention for his digs, even getting sponsorship from the Daily Mail. He also highlighted the site's connection to the legends of King Arthur.

In 1924, Wheeler became the Director of the National Museum of Wales. He worked to connect the museum with smaller regional museums and raised a lot of money to finish the new museum building. The new building was officially opened by King George V in 1927.

London Museum: 1926–1933

In July 1926, Wheeler was invited to become the Keeper of the London Museum. He was excited to return to London. He and Tessa worked hard to make the museum more professional. He reorganized the exhibits and improved how artifacts were cataloged. He also wrote books about London's history, like London and the Romans.

Wheeler convinced the government to increase the museum's budget, which allowed him to hire more staff. He also became involved with the Society of Antiquaries, helping to organize archaeological work in London. In 1927, he started teaching archaeology at University College London, creating a special course for students.

Wheeler continued to lead archaeological digs outside London every year. After finishing his work at Caerleon, he began excavating at Lydney Park in Gloucestershire. There, he found the Lydney Hoard of ancient coins. He and Tessa published a detailed report on their findings.

From 1930 to 1933, Wheeler directed an excavation at the Roman town of Verulamium. He was especially interested in finding evidence of an earlier Iron Age settlement there. Tessa focused on digging inside the city walls. Their report, Verulamium: A Belgic and Two Roman Cities, was published in 1936.

Institute of Archaeology: 1934–1939

Wheeler had a big dream: to create a special academic place in London just for archaeology. He wanted it to be a center for training archaeologists with the best methods. In 1934, the Institute of Archaeology officially opened. Wheeler became its Honorary Director, even though he was still working at the London Museum.

After his work at Verulamium, Wheeler turned his attention to Maiden Castle, a large Iron Age hill fort near Dorchester, Dorset. He led excavations there from 1934 to 1937. This was the biggest dig in Britain at the time, with about 100 assistants each season. Wheeler made sure to share discoveries with the press, showing archaeology as a modern and exciting field.

In 1936, Wheeler visited archaeological sites in the Near East. While he was away, his wife Tessa sadly passed away. That winter, his father also died. In 1939, Wheeler married Mavis de Vere Cole.

After a long search, Wheeler found a home for the Institute of Archaeology: St. John's Lodge in Regent's Park, London. The building was officially opened in April 1937. Wheeler also became President of the Museums Association, where he spoke about protecting museum collections during wartime, as he felt another war was coming.

In 1939, Wheeler began excavations in France at Iron Age hill forts like Camp de Canada. However, this work was cut short in September 1939 when World War II began, and his team had to return to Britain.

Military Service in World War II

North Africa and Italy: 1939–1945

Wheeler had expected World War II to break out. He rejoined the armed forces on July 18, 1939, as a major. He helped create the 42nd Mobile Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment in the Royal Artillery and became its Commanding Officer, now a lieutenant-colonel.

In the summer of 1941, Wheeler and his batteries were sent to fight German and Italian forces in the North African Campaign. They sailed from Glasgow, going around the Cape of Good Hope to reach Egypt. Wheeler even flew as a front gunner in a bomber to understand what it was like to be fired upon by anti-aircraft guns.

Serving with the Eighth Army, Wheeler was present when the Axis armies pushed the Allies back to El Alamein. He also took part in the Allied counter-attack, including the Second Battle of El Alamein. As they advanced, Wheeler became worried about archaeological sites in North Africa being damaged by fighting and soldiers. He gave talks to troops about protecting ancient monuments and made sure some sites were off-limits.

On May 1, 1943, he was promoted to brigadier. After the Germans surrendered in North Africa, Wheeler helped plan the Allied invasion of Italy. He insisted that steps be taken to protect historic sites on the island of Sicily and mainland Italy. Wheeler and his unit then took part in the invasion of Italy.

In November 1943, Wheeler returned to London. He resigned from the London Museum and prepared the Institute of Archaeology for a new director. He also developed a relationship with Kim Collingridge and married her in 1945. In February 1944, he sailed to India.

Archaeological Survey of India: 1944–1948

Wheeler arrived in India in the spring of 1944 to become the Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India. He found the archaeological work there needed a lot of improvement. He worked hard to reform the Survey, improving its finances and equipment. He also planned for a National Museum of Archaeology to be built in New Delhi.

In October 1944, he started a six-month archaeological field school in Taxila, teaching students from all over India about archaeological methods. Wheeler became very fond of his students. He was especially interested in the ancient Indus Valley civilization. He led excavations at sites like Harappa, where he found fortifications and learned about the settlement's layers of history.

Turning his attention to southern India, Wheeler found Roman pottery in a museum. This led him to excavate Arikamedu, where he discovered a port from the 1st century CE that had traded with the Roman Empire. He also dug at Brahmagiri, finding megalithic tombs that helped him create a timeline for southern Indian archaeology.

Wheeler started a new archaeological journal called Ancient India. He married Kim Collingridge in India. He also led cultural missions to Iran and Afghanistan.

Wheeler was in India during the Partition of India in 1947, when India was divided into two countries, India and Pakistan. He was sad that this split up his archaeological team. He helped many of his Muslim staff members escape violence in Delhi. As India became independent, Wheeler realized it was time for him to leave. For his work in India, he was honored with the Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE).

His wife had returned to Britain. Wheeler decided to take a part-time professorship at the Institute of Archaeology in London. He also agreed to advise the Pakistani government on archaeology for a few months each year. In September 1948, he officially ended his military service.

Later Life and Public Fame

Between Britain and Pakistan: 1948–1952

Back in London, Wheeler started lecturing at the Institute of Archaeology. In April 1949, he was nominated for President of the Society of Antiquaries. He lost, but was still elected director of the Society. In 1950, he was awarded the Petrie Medal. In 1952, he was knighted by the Queen at Buckingham Palace, becoming "Sir Mortimer Wheeler".

Wheeler spent three months in Pakistan in early 1949, helping to set up the new Pakistani Archaeological Department. He helped establish a National Museum of Pakistan in Karachi, which opened in April 1950. He also wrote a book called Five Thousand Years of Pakistan.

In early 1950, Wheeler led a training excavation at Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan to teach new students. He later wrote about his findings in his book The Indus Civilization.

Wheeler was keen to dig in Britain again. In 1949, he ran an archaeological training course at Verulamium. From 1951 to 1952, he excavated the Stanwick Iron Age Fortifications in North Riding, Yorkshire, with many friends and colleagues. He published his report on the site in 1954.

In 1949, Wheeler became Honorary Secretary of the British Academy. He worked hard to make the organization more active and successful. He helped increase its funding from the British government, making it a major supporter of humanities research in the UK.

Media Fame and Public Archaeology

Wheeler became very famous in Britain as "the face of popular archaeology" on television. In 1952, he joined the new BBC television series Animal, Vegetable, Mineral?. On the show, he and other experts tried to identify artifacts from museums. The show was very popular and ran for six years, making Wheeler a household name. He even won a Television Personality of the Year award in 1954. He also appeared on other archaeology shows, traveling to places like Pakistan and Great Zimbabwe.

From 1954 onwards, Wheeler spent more time encouraging public interest in archaeology. He published two books in 1954: Archaeology from the Earth, about archaeological methods, and Rome Beyond the Imperial Frontier, about Roman activity outside the empire. In 1955, he released his autobiography, Still Digging, which sold over 70,000 copies. He also wrote books like Early India and Pakistan and Flames Over Persepolis.

In 1955, a tour company invited Wheeler to give lectures on ancient Greek archaeology aboard their cruises. He later became chairman of their Hellenic Cruise division, leading two tours a year. He also led tours to the Indian subcontinent.

Wheeler continued his archaeological work. In 1956, he returned to Pakistan to excavate at Charsada. From 1965 to 1970, he was President of the Camelot Research Committee, which promoted excavations at Cadbury Castle. He also chaired the committee overseeing excavations at York Minster.

He campaigned for more government funding for museums. In 1963, he became a trustee of the British Museum, but he publicly criticized it for being poorly managed.

British Academy and UNESCO

As Honorary Secretary of the British Academy, Wheeler worked to increase its income. He convinced the British government to double its funding for the academy. He also secured money from other charitable foundations. With this extra money, the academy could expand its work.

Wheeler also pushed for new British archaeological institutes abroad. In 1961, an institute was established in Dar es Salaam, East Africa, and later moved to Nairobi. In 1960, a British Institute of Persian Studies was opened in Tehran, Iran. He visited these institutes and other British schools abroad. In 1969, he resigned as Honorary Secretary of the academy.

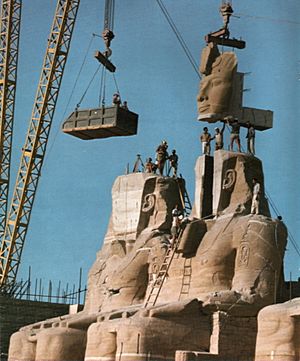

Because of his importance in archaeology, Wheeler was chosen to represent Britain on a UNESCO project. This project aimed to save archaeological sites in the Nile Valley before the construction of the Aswan Dam flooded them. He helped secure UK funding for this project. In October 1968, he visited Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan with UNESCO to assess how to preserve the site.

Final Years: 1970–1976

In his final years, Wheeler remained active in archaeology. In 1971, a conference was held to celebrate his 80th birthday. In 1973, he appeared on two episodes of the BBC archaeology series Chronicle, discussing his life and career.

As his health declined, he became more forgetful and relied on his assistant, Molly Myres. In September 1973, he moved into her house in Leatherhead, Surrey. He wrote one last book, My Archaeological Mission to India and Pakistan, which was published in 1976.

Sir Mortimer Wheeler passed away on July 22, 1976, after a stroke. His funeral was held with full military honors, and a larger memorial service took place in London.

Personal Life

Mortimer Wheeler was known as "Rik" to his friends. People had strong opinions about him; some loved him, while others found him difficult. He was known for being a strong leader on his excavations. He was very careful with his writing, always revising and rewriting his work. He was also a heavy smoker throughout his life.

Wheeler was married three times. In May 1914, he married Tessa Verney. Tessa was also a talented archaeologist, and they worked together until her death in 1936. Their only child, Michael Mortimer Wheeler, was born in 1915 and became a lawyer.

In 1939, Wheeler married Mavis de Vere Cole. Their relationship was difficult. In 1945, Mortimer Wheeler married his third wife, Margaret Collingridge. They became separated in 1956, but they could not divorce due to her religious beliefs.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |