Great Zimbabwe facts for kids

Tower in the Great Enclosure, Great Zimbabwe

|

|

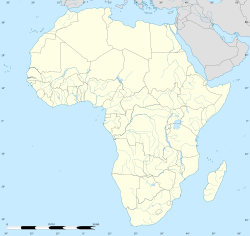

| Location | Masvingo Province, Zimbabwe |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 20°16′S 30°56′E / 20.267°S 30.933°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Part of | Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe |

| Area | 7.22 km2 (2.79 sq mi) |

| History | |

| Material | Granite |

| Founded | 11th century CE |

| Abandoned | 16th or 17th century |

| Periods | Late Iron Age |

| Cultures | Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | Great Zimbabwe National Monument |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, vi |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

Great Zimbabwe was an amazing ancient city in the southeastern hills of the country we now call Zimbabwe. It was first settled around 1000 CE and became the capital of a powerful kingdom in the 13th century. This city is the largest stone structure built in Southern Africa before European colonization.

People started building the main stone structures in the 11th century, and construction continued until the 15th century. The city was eventually left empty in the 16th or 17th century. The impressive buildings were created by the ancestors of the Shona people, who still live in Zimbabwe and nearby countries today. Great Zimbabwe covered an area of about 7.22 square kilometers (2.79 square miles) and could have been home to as many as 18,000 people at its busiest time. The kingdom it led likely spread over 50,000 square kilometers (19,000 square miles). Today, UNESCO recognizes Great Zimbabwe as a special World Heritage Site.

The site has three main parts: the Hill Complex, the Valley Complex, and the Great Enclosure. Each part was built at different times. Experts still discuss what each area was used for. Some think they were homes for kings and important people, while others believe they had different purposes. The Great Enclosure is especially famous for its tall walls, which are about 11 meters (36 feet) high. These walls were built using a special "dry stone" method, meaning no mortar was used to hold the stones together! This part was built in the 13th and 14th centuries and was probably where the royal family lived, with special areas for important ceremonies.

The first time Europeans wrote about Great Zimbabwe was in 1531. A Portuguese captain named Vicente Pegado called it Symbaoe. Europeans didn't visit the site until the late 1800s, and serious studies began in 1871. Sadly, between the 1890s and 1920s, many valuable items were taken from Great Zimbabwe by early explorers. For a long time, there were unfair ideas about who built the city. Some people in power tried to stop archaeologists from saying that local African people built it. But by the 1950s, it became clear to everyone that Africans were indeed the builders. The government of Zimbabwe now proudly protects Great Zimbabwe as a national monument, and the country itself is named after this incredible ancient city.

The word Great in Great Zimbabwe helps us tell it apart from many other smaller stone ruins. These smaller sites are also called "zimbabwes" and are found all over the Zimbabwe Highveld region. There are about 200 such places in Southern Africa, like Bumbusi in Zimbabwe and Manyikeni in Mozambique. They all feature impressive walls built without mortar.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Zimbabwe comes from the Shona language. It was first written down in 1531 by Vicente Pegado, a Portuguese captain. He said that the local people called these buildings Symbaoe, which meant 'court' in their language.

The word Zimbabwe includes the Shona word dzimba, meaning 'houses'. There are two main ideas about where the name comes from:

- Some believe it comes from Dzimba-dze-mabwe, which means 'large houses of stone'. Here, dzimba is the plural of 'house', and mabwe is the plural of 'stone'.

- Another idea is that Zimbabwe is a shorter version of dzimba-hwe. In the Zezuru dialect of Shona, this means 'venerated houses', often used for the homes or burial places of important leaders.

The Story of Great Zimbabwe

Early Settlers and Builders

Long before Great Zimbabwe was built, the area was home to the San people about 100,000 years ago. Around 150 BCE, Bantu-speaking groups arrived. They started farming and forming small communities called chiefdoms by the 4th century CE.

From the 4th to the 7th centuries, people from the Gokomere or Ziwa cultures lived in the valley. They farmed, mined, and worked with iron. However, they didn't build any stone structures. These were the first Iron Age settlements found by archaeologists. Later, the Gumanye people are thought to be the ancestors of the Karanga people. The Karanga are a group of the Shona people who eventually built Great Zimbabwe.

Building the Stone City

Building the amazing stone structures of Great Zimbabwe began in the 11th century. This work continued for more than 300 years! These ruins are among the oldest and largest in all of Southern Africa.

The most impressive building is called the Great Enclosure. Its walls are about 11 meters (36 feet) high and stretch for about 250 meters (820 feet). The city's growth might have been connected to the decline of another city called Mapungubwe around 1300. It could also be due to more gold being found in the areas around Great Zimbabwe.

At its busiest, Great Zimbabwe might have been home to up to 18,000 people. However, some newer studies suggest the population was closer to 10,000. The ruins we see today are all made of stone and cover about 728 hectares (1,800 acres). This is a huge area, similar in size to medieval London! Inside the stone walls, buildings were packed closely together. Outside, they were more spread out.

The leaders of Great Zimbabwe, called mambos, used their beliefs and traditions to strengthen their rule. They connected themselves to their ancestors and to Mwari, their God. It's believed that the Hill Complex had a special shrine. Here, spirit mediums, known as svikiro, helped guide the state and kept the old traditions alive.

Most people in Great Zimbabwe lived in houses made of mud and wood. We can only guess how many of these houses there were. The stone buildings were likely for the royal family, important officials, and wealthy people. No burial sites have been found, which makes it harder to estimate the exact population.

Exploring the Ruins

In 1531, Vicente Pegado described Great Zimbabwe as a "fortress built of stones of marvelous size." He noted that no mortar was used to join the stones. He also mentioned a tall tower, over 22 meters (72 feet) high.

The ruins are divided into three main groups:

- The Hill Complex

- The Valley Complex

- The Great Enclosure

The Hill Complex is the oldest part, used from the 11th to 13th centuries. The Great Enclosure was used from the 13th to 15th centuries. The Valley Complex was used from the 14th to 16th centuries.

Important features of the Hill Complex include the Eastern Enclosure. This is where the famous Zimbabwe Bird sculptures might have stood. There's also a high balcony overlooking this enclosure and a huge boulder shaped like the Zimbabwe Bird.

The Great Enclosure has an inner wall surrounding several structures, and a younger outer wall. The Conical Tower, about 5.5 meters (18 feet) wide and 9 meters (30 feet) high, was built between these two walls. The Valley Complex is split into Upper and Lower Valley Ruins, used at different times.

Archaeologists have different ideas about what these areas were for. Some think new kings built new homes, so power moved from the Hill Complex to the Great Enclosure, then to the Valley. Others believe each complex had a different purpose. For example, the Hill Complex might have been for rituals, the Valley Complex for citizens, and the Great Enclosure for the king.

The people of Great Zimbabwe also used Dhaka pits. These were special holes in the ground that helped them manage water. They acted as reservoirs, wells, and springs, holding over 18,000 cubic meters (635,664 cubic feet) of water!

Amazing Artefacts

The most important discoveries at Great Zimbabwe are the eight Zimbabwe Birds. These birds were carved from a soft stone called soapstone and placed on top of tall stone pillars. Slots in a platform in the Hill Complex suggest where they might have stood.

Other cool finds include soapstone figures, pottery, iron gongs, beautiful ivory carvings, and tools made of iron and copper. They also found gold beads, bracelets, and pendants. Glass beads and porcelain from China and Persia show that Great Zimbabwe traded with faraway lands. These birds are thought to represent the bateleur eagle, which was seen as a good omen and a messenger of the gods in Shona culture.

Trade and Gold

Great Zimbabwe became a major trading hub around 1300, taking over from Mapungubwe. Its trade networks reached far and wide. Salt, cattle, grain, and copper were traded as far north as the Kundelungu Plateau in what is now the DR Congo.

A lot of Great Zimbabwe's wealth came from controlling trade routes. These routes connected the goldfields of the Zimbabwean Plateau to the Swahili coast. Through Swahili city-states like Sofala, they exported gold and ivory across the Indian Ocean trade. Besides international trade, there was also local farming trade, with cattle being very important.

Archaeologists have found Chinese pottery, coins from Arabia, and glass beads at Great Zimbabwe. These items prove the city's strong connections to international trade.

Gold Working Skills

Great Zimbabwe was also a key place for working with gold. Discoveries show that gold production was a special skill, not something everyone did. Recent studies found leftover pieces from gold working, confirming that gold was processed in certain areas of the site. This means gold working was a big part of their craft traditions and important to their economy. Excavations have uncovered clay containers, crucibles, and tools used to heat gold and shape it into wire, beads, or decorations. These findings help us understand the skilled artisans of Great Zimbabwe and gold's major role in their culture.

Why the City Declined

We don't know exactly why Great Zimbabwe eventually declined and was abandoned. It's unlikely that climate change was the main reason, as the city was in a good rainfall area. Great Zimbabwe's power depended on its ability to expand. Its growing population needed more farmland, and traders needed more gold.

Shona oral traditions suggest a salt shortage led to the city's decline. This might be a way of saying that the land became less fertile for farming, or that other important resources ran out. It's also possible that the underground water supply ran low or became polluted as the population grew.

From the early 15th century, international trade slowed down due to a global economic downturn. This reduced the demand for gold, which hurt Great Zimbabwe. In response, leaders might have expanded their regional trade networks. This led to other settlements in the region becoming more prosperous.

By the late 15th century, new kingdoms started to form, possibly by members of Great Zimbabwe's royal family who left after disagreements. According to oral tradition, Nyatsimba Mutota led some people north to find salt, founding the Mutapa Empire. It was believed that only their newer ancestors would follow them, while older ancestors stayed at Great Zimbabwe to protect it. New trade routes opened, shifting power away from Great Zimbabwe to the north and west. By the 16th century, Khami, the capital of the Kingdom of Butua, had risen in importance. Great Zimbabwe was likely still inhabited into the 17th century before it was finally abandoned.

Discovering Great Zimbabwe's Past

For a long time, there was much debate about who built Great Zimbabwe. This was known as the "Zimbabwe controversy". Sadly, some early European visitors had unfair ideas. They found it hard to believe that local African people could have built such impressive structures. They even suggested that archaeological finds like Persian bowls and Chinese pottery meant non-African people built it.

The colonial government at the time tried to pressure archaeologists to deny that Africans built the structures. This was because acknowledging the truth would have challenged their own ideas about their "civilising mission." Many strange theories were suggested, blaming Jews, Arabs, Phoenicians, or anyone but the Shona people. This struggle to prove its African origin continued throughout the 20th century. By the 1950s, it finally became widely accepted among archaeologists that Africans were indeed the builders.

Early European Accounts

The first European to visit the region might have been António Fernandes between 1513 and 1515. He described fortified stone centers without mortar. However, he didn't specifically mention Great Zimbabwe. Portuguese traders heard about the city's ruins in the early 16th century. Their records link Great Zimbabwe to gold production and long-distance trade. Some accounts even mention an inscription above the entrance, written in unknown characters.

In 1506, explorer Diogo de Alcáçova described the buildings in a letter. He said they were part of the larger kingdom of Ucalanga (likely Karanga, a Shona dialect). João de Barros also wrote about Great Zimbabwe in 1538, based on stories from Moorish traders. He noted that the buildings were locally known as Symbaoe, meaning "royal court."

De Barros wrote about the builders:

When and by whom, these edifices were raised, as the people of the land are ignorant of the art of writing, there is no record, but they say they are the work of the devil, for in comparison with their power and knowledge it does not seem possible to them that they should be the work of man.

He also believed the city was built to protect gold mines. De Barros mentioned that Symbaoe was still guarded by a nobleman and housed some of the king's wives. This suggests the site was still active in the early 16th century.

Karl Mauch and the Queen of Sheba

The ruins were rediscovered by Europeans during a hunting trip in 1867 by Adam Render, a German-American hunter. In 1871, he showed the ruins to Karl Mauch, a German explorer. Mauch immediately dismissed the idea that local people built them. He started speculating about a connection to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba from the Bible. This idea had been suggested by earlier writers. Mauch even claimed a wooden beam at the site must be Lebanese cedar, brought by Phoenicians. This legend became very popular among white settlers.

Early Explorers and Damage

After Mauch's visit, several people came to the ruins, some working for W.G. Neal's Ancient Ruins Company. Willi Posselt was one of the first to take a soapstone bird from the site. Over several years, Neal and his company took many valuable items, destroying parts of the ruins in the process. It's unclear how many artefacts were lost or damaged.

Carl Peters collected a ceramic figure in 1905. Experts later identified it as a forgery, not a genuine ancient Egyptian artefact.

J. Theodore Bent conducted excavations with funding from Cecil Rhodes. He had no formal archaeological training. He carelessly dug into the Conical Tower, which damaged the site and made it impossible to determine the tower's age later. Many artefacts were also lost during his visit. Bent believed the ruins were built by a "Semitic race and of Arabian origin" of traders.

The Lemba People's Claim

The Lemba people also claim to have built Great Zimbabwe. This was recorded by William Bolts in 1777 and A. A. Anderson in the 19th century. The Lemba speak Bantu languages but have some religious practices similar to Judaism and Islam, which they say were passed down through stories.

Scientific Archaeology Begins

The first scientific archaeological excavations were done by David Randall-MacIver in 1905–1906. In his book Medieval Rhodesia, he disagreed with earlier claims and stated that the objects found were of Bantu origin. Randall-MacIver concluded that the structures were built by the ancestors of the Shona people. He also suggested a medieval date for the walls and temple. His findings were not immediately accepted, partly because his excavation was short.

In 1929, Gertrude Caton Thompson also concluded that the site was built by Bantu people after a twelve-day visit. She dug test pits and found pottery, ironwork, glass beads, and a gold bracelet. She announced her theory that the site was of Bantu origin and medieval date. Her modern methods gained strong support among some archaeologists. By 1931, she suggested a possible Arabian influence for the towers, perhaps from buildings seen in coastal Arabian trading cities.

Modern Research and African Origins

Since the 1950s, archaeologists have generally agreed that Great Zimbabwe was built by Africans. Artefacts and radiocarbon dating show continuous settlement between the 12th and 15th centuries. Dated finds like Chinese, Persian, and Syrian artefacts also support these dates.

Archaeologists believe the builders spoke one of the Shona languages. This is based on pottery, oral traditions, and DNA evidence. Recent studies suggest that the Shona people and Venda peoples, likely descended from the Gokomere culture, built Great Zimbabwe. The Gokomere culture existed in the area from around 200 AD and flourished from 500 AD to 800 AD.

Recent archaeological work has been done by Peter Garlake, David Beach, Thomas Huffman, and Gilbert Pwiti. Today, the most accepted idea is that the Shona people built Great Zimbabwe. Some evidence also points to an early influence from the Venda-speaking peoples of the Mapungubwe civilization.

Damage to the Ruins

Sadly, the ruins have been damaged over the last century. Early European explorers took many valuable items from the 1890s to the 1920s. This made it much harder for later archaeologists to study the site properly. Mining for gold also caused extensive damage. Even some reconstruction attempts after 1980 caused more harm.

Visitors have also caused damage by climbing walls, walking over important archaeological areas, and overusing certain paths. Natural weathering, like plant growth, settling foundations, and erosion, also slowly damages the structures.

Great Zimbabwe's Importance Today

The history of Great Zimbabwe has been used by different groups to support their ideas about the country. Early colonialists saw the ruins as a sign of wealth. Some scholars, like Gertrude Caton-Thompson, recognized African builders but described the site in ways that were not fair.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the government of Rhodesia tried to control information. They wanted to deny that Black Africans built the structures. Archaeologists who disagreed were silenced. Paul Sinclair, an archaeologist, said he was told to be "extremely careful" about talking to the press. He was even threatened with losing his job if he said Black people built Zimbabwe. This control of information led to important archaeologists leaving the country.

For Black nationalist groups, Great Zimbabwe became a powerful symbol of African achievement. Reclaiming its true history was a major goal for those seeking fair rule. In 1980, when the country became independent, it was renamed Zimbabwe after the site. The famous soapstone bird carvings became a national symbol, appearing on the new Zimbabwean flag.

After 1980, Great Zimbabwe has been used to reflect and support the policies of the ruling government. At first, it was seen as representing "African socialism." Later, the focus shifted to showing how wealth and power grew within a ruling group.

Some of the original bird carvings were taken around 1890 and sold to Cecil Rhodes. Most of these carvings have now been returned to Zimbabwe. However, one remains at Rhodes' old home, Groote Schuur, in Cape Town.

Local Views

Local communities, even though different clans claim the site, share similar feelings. They are sad that early European explorers and even some archaeologists treated the sacred site without respect. They also believe the government should do more to acknowledge the local ancestors and Mwari as owners and protectors of the site.

Great Zimbabwe University

In the early 21st century, the government of Zimbabwe supported the creation of a university near the ruins. This university focuses on arts and culture, drawing inspiration from the rich history of the monuments. The main campus is close to the monuments, with other campuses in the city center and Mashava. These include schools for Law, Education, Agriculture, Arts, and Commerce.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Gran Zimbabue para niños

In Spanish: Gran Zimbabue para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |