History of the United Kingdom during the First World War facts for kids

| 1914–1918 | |

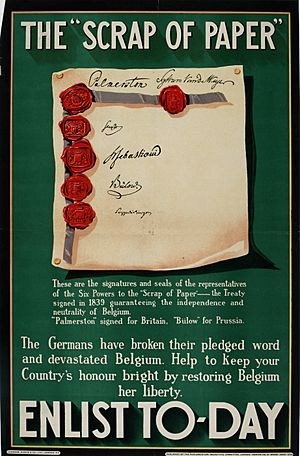

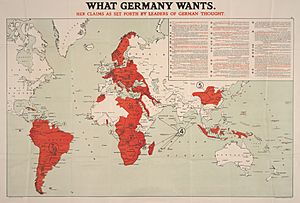

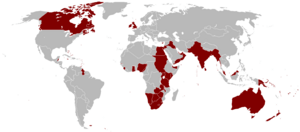

British First World War propaganda poster

|

|

| Preceded by | Edwardian era |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Interwar Britain |

| Monarch | George V |

| Leader(s) |

Army

Royal Navy

|

The United Kingdom was a main Allied Power during the First World War from 1914 to 1918. They fought against the Central Powers, mainly Germany. Britain's armed forces grew a lot and were reorganized. The Royal Air Force was even created during this time. In January 1916, for the first time in British history, the government started using conscription. This meant men had to join the army, even though over 2 million men had already volunteered for Kitchener's Army. When the war started in 1914, most people were excited and united, much like in other parts of Europe.

Before the war, there were big disagreements in Britain about workers' rights and women's right to vote. But these issues were put on hold. People were asked to make big sacrifices to defeat the enemy. Many who couldn't fight helped with charity work. The government passed laws like the Defence of the Realm Act 1914 to get new powers. This was to prevent food shortages and lack of workers. At first, Prime Minister H. H. Asquith wanted to keep "business as usual". But by 1917, under Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Britain moved towards "total war". This meant the government took complete control over public life. It was the first time Britain had done this. British cities also faced air attacks for the first time.

Newspapers helped keep people supporting the war. The government created a lot of propaganda, guided by journalists like Charles Masterman and newspaper owners like Lord Beaverbrook. Industries related to the war grew quickly. Production increased as more women started working in jobs usually done by men. This was called "dilution of labour." Some people believe the war helped women get jobs they hadn't had before. Many women also got the right to vote for the first time in 1918. But each woman's experience during the war was different. It depended on where she lived, her age, if she was married, and her job.

The number of civilians who died went up because of food shortages and the Spanish flu in 1918. Over 850,000 soldiers died. After the war, the British Empire was at its largest. But the war also made people in countries like Canada, Australia, and India feel more proud of their own national identities. After 1916, Irish nationalists wanted immediate independence, especially after the Conscription Crisis of 1918. In the UK, people generally had a negative view of the war. However, some historians disagree. Research for the war's 100-year anniversary showed that many people today see Britain's role in the war positively. But they often think the generals didn't do a good job. Also, some details about World War I are often confused with World War II.

Contents

- Government Leadership During the War

- The Royal Family During Wartime

- The Defence of the Realm Act

- Internment of Foreigners

- Britain's Armed Forces

- Joining the Army and Conscription

- Attacks from Sea and Air

- Media and Public Opinion

- Economic Changes During the War

- Social Changes in Britain

- Conditions Across British Regions

- War Casualties

- The War's Impact and Memory

- Images for kids

- See also

Government Leadership During the War

Prime Minister Asquith's Role

On August 4, 1914, King George V declared war. He followed the advice of his prime minister, H. H. Asquith, who led the Liberal Party. Britain went to war mainly because it had promised to support France. Also, top Liberals threatened to quit if the government didn't help France. This would have made the Liberal Party lose control.

However, many Liberals were against the war. They agreed to support it to honor a treaty from 1839 that protected Belgium's neutrality. So, the government told the public that Britain had to protect Belgium. This was the main reason given in posters.

Britain worried that if Germany controlled Belgium and France's coast, it would be a big danger. Germany's casual attitude towards Belgium's neutrality made Britain doubt its promises. But the 1839 treaty didn't force Britain to protect Belgium alone. Also, Britain's own naval plans showed it might have broken Belgium's neutrality by blocking its ports during a war with Germany.

Britain's duty to its allies, France and Russia, was very important. The Foreign Secretary, Edward Grey, said that secret naval agreements with France meant Britain had a moral duty to save France from Germany. Britain didn't want Germany to control France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Grey warned that abandoning its allies would be a disaster. If Germany won, or if the allies won without Britain, Britain would be left without friends. This would leave Britain and its Empire vulnerable.

A senior expert in the Foreign Office, Eyre Crowe, said:

If war happens and England stays out, one of two things will occur. (a) Germany and Austria win, crushing France and humiliating Russia. What will happen to a friendless England? (b) Or France and Russia win. How would they treat England? What about India and the Mediterranean?

Changes in Liberal Leadership

The Liberal Party might have survived a short war. But the huge scale of the Great War needed strong actions that the party had always avoided. This led to the Liberal Party losing its ability to lead the government forever. Historian Robert Blake explains the problem:

- The Liberals were known for freedom of speech, belief, and trade. They were against aggressive nationalism, large armies, and forced actions. Liberals were not fully united about conscription, censorship, the Defence of the Realm Act, being harsh to foreigners, or controlling workers and industries. The Conservatives had no such doubts.

Blake also noted that Liberals needed the moral outrage over Belgium to justify going to war. Conservatives, however, wanted to intervene from the start. They focused on what was best for Britain and the balance of power.

People in Britain were disappointed that the war wasn't ending quickly. They were proud of the Royal Navy, but there wasn't much good news. The Battle of Jutland in May 1916 was the only time the German fleet seriously challenged Britain's control of the North Sea. But the German fleet was outmatched and mostly helped U-boats after that. Since Liberals ran the war without asking the Conservatives, there were many political attacks. Even Liberal writers were upset by the lack of energy from the top leaders. At the time, public opinion was very angry, both in newspapers and on the streets, against any young man not in uniform, calling them "slackers." The main Liberal newspaper, the Manchester Guardian, complained:

- The fact that the Government has not dared to challenge the nation to rise above itself, is one among many signs... The war is, in fact, not being taken seriously.... How can any slacker be blamed when the Government itself is slack.

Asquith's Liberal government fell in May 1915. This was mainly because of a shortage of artillery shells. Also, Admiral Fisher resigned in protest over the terrible Gallipoli Campaign against Turkey. Asquith didn't want to face an election he might lose. So, he formed a new government on May 25. Most of the new cabinet came from his own Liberal party and the Unionist (Conservative) party. There was also a small Labour Party presence. This new government lasted a year and a half. It was the last time Liberals controlled the government. Historian A. J. P. Taylor said that the British people were very divided. But everyone was losing trust in Asquith's government. There was no agreement on war issues. The leaders of both parties knew that angry debates in Parliament would make public morale worse. So, the House of Commons didn't discuss the war once before May 1915. Taylor explained:

- The Unionists, generally, saw Germany as a dangerous rival. They were happy to have a chance to destroy her. They wanted to fight a tough war using harsh methods. They criticized Liberal "softness" before and during the war. The Liberals insisted on staying noble. Many only supported the war after Germany invaded Belgium. Entering the war for good reasons, Liberals wanted to fight it nobly. They found it harder to give up their principles than to accept defeat on the battlefield.

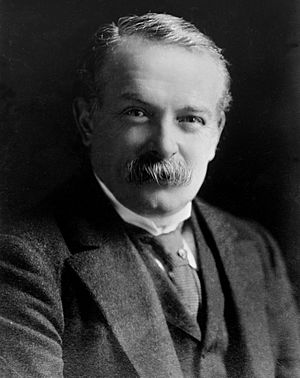

Lloyd George Becomes Prime Minister

This coalition government lasted until 1916. Then, the Unionists became unhappy with Asquith and the Liberals' handling of the war, especially after the Battle of the Somme. Asquith's opponents took control. They were led by Bonar Law (Conservative leader), Sir Edward Carson (Ulster Unionist leader), and David Lloyd George (a minister in the cabinet). Law didn't have enough support to form a new government. But Lloyd George, a Liberal, had much wider support. So, he formed a new government with mostly Conservatives, plus his own Liberal supporters and Labour. Asquith was still the Liberal party head, but he and his followers moved to the opposition in Parliament.

Lloyd George immediately started changing Britain's war effort. He took strong control of both military and domestic policy. In its first 235 days, the War Cabinet met 200 times. This marked the start of "total war". This idea meant that everyone—men, women, and children—should help with the war effort. Also, it was decided that government members should be the ones controlling the war. They mainly used the powers given to them by the Defence of the Realm Act. For the first time, the government could act quickly. There was less bureaucracy, and they had up-to-date information on things like merchant ships and farm production. This policy was a big change from Asquith's earlier approach. Asquith's policy was described by Winston Churchill as "business as usual" in November 1914. Lloyd George's government succeeded partly because people didn't want another election. This meant there was less disagreement.

In spring 1918, several military and political problems arose quickly. Germany had moved troops from the Eastern Front and trained them in new ways. Now, they had more soldiers on the Western Front than the Allies. On March 21, 1918, Germany launched a huge Spring Offensive against British and French lines. They hoped to win the war before many American troops arrived. The Allied armies retreated 40 miles in confusion. Facing defeat, London realized it needed more troops for a mobile war. Lloyd George found half a million soldiers and quickly sent them to France. He asked American President Woodrow Wilson for immediate help. He also agreed to appoint French General Foch as commander in chief on the Western Front. This helped Allied forces work together against the German attack.

Even though there were strong warnings against it, the War Cabinet decided to force conscription on Ireland in 1918. The main reason was that workers in Britain demanded it. They wanted it as a condition for reducing exemptions from conscription for certain workers. Labour wanted the rule that no one was exempt. But they didn't demand that conscription actually happen in Ireland. The plan was passed into law, but it was never enforced. Roman Catholic bishops spoke out for the first time, calling for open resistance to forced military service. Most Irish nationalists then started supporting the Sinn Féin movement, moving away from the Irish National Party. This was a key moment, showing that Ireland no longer wanted to stay in the Union.

On May 7, 1918, a senior army officer, Major-General Sir Frederick Maurice, caused another crisis. He publicly claimed that Lloyd George had lied to Parliament about troop numbers in France. Asquith, the Liberal leader in the House, brought up these claims and attacked Lloyd George (who was also a Liberal). Asquith's presentation was weak. But Lloyd George strongly defended himself, treating the debate as a vote of confidence. He won over the House by powerfully disproving Maurice's claims. The main results were that Lloyd George became stronger, Asquith became weaker, public criticism of the war strategy ended, and civilian control over the military increased. Meanwhile, the German attack stopped and was eventually pushed back. Victory came on November 11, 1918.

Historian George H. Cassar has looked at Lloyd George's time as a war leader:

- After all that has been said and done, what are we to make of Lloyd George’s legacy as a war leader? On the home front he achieved varied results in tackling difficult, and in some instances, unprecedented problems. It would be hard to have improved on his dealings with labour and the program to increase homegrown food, but in the sectors of manpower, price control and food distribution he adopted the same approach as his predecessor, taking action only in response to the changing nature of the conflict. In the vital area of national morale, while he did not have the technical advantages of Churchill, his personal conduct damaged his ability to do more to inspire the nation. All things considered, it is unlikely that any of his political contemporaries could have handled matters at home as effectively as he did, although it can be argued that if someone else had been in charge, the difference would not have been sufficient to change the final outcome. In his conduct of the war he did advance the cause of the Entente significantly in some ways, but in determining strategy, one of the most important tasks for which a prime minister must be responsible, he was undeniably a failure. To sum up, while Lloyd George's contributions outweighed his mistakes, the margin is too narrow, in my opinion, to include him In the pantheon of Britain's outstanding war leaders.

The Liberal Party's Decline

In the general election of 1918, Lloyd George, known as "the Man Who Won the War," led his coalition to a huge victory. He defeated the Liberals who supported Asquith and the rising Labour Party. Lloyd George and Conservative leader Bonar Law wrote a joint letter. This letter supported candidates who were considered the official Coalition candidates. This ""coupon"," as it was called, was given to opponents of many sitting Liberal Members of Parliament. This greatly hurt the Liberals in power. Asquith and most of his Liberal colleagues lost their seats. Lloyd George became more and more influenced by the stronger Conservative party. The Liberal party never fully recovered after this.

How Britain Paid for the War

Before the war, the government spent 13 percent of the country's total income (GNP). In 1918, it spent 59 percent of GNP. The war was paid for by borrowing a lot of money from within Britain and from other countries. New taxes were also introduced, and inflation increased. The government also saved money by delaying maintenance and repairs, and by canceling projects that weren't essential.

The government avoided indirect taxes because they made living costs higher. This would have made working-class people unhappy. In 1913–14, indirect taxes on tobacco and alcohol brought in £75 million. Direct taxes brought in £88 million, including £44 million from income tax and £22 million from estate duties. This means 54 percent of the money came from direct taxes. By 1918, direct taxes made up 80 percent of the money. There was a strong focus on being "fair" and "scientific" with taxes. The public generally supported the new high taxes with few complaints.

The Treasury rejected ideas for a big tax on wealth, which the Labour Party wanted to use to weaken rich people. Instead, there was an excess profits tax. This was 50 percent of profits above the normal pre-war level. The rate was raised to 80 percent in 1917. Extra taxes were added on luxury imports like cars, clocks, and watches. There was no sales tax or value-added tax. The biggest increase in money came from income tax. In 1915, it went up to 17.5%, and individual tax exemptions were lowered. The income tax rate grew to 25% in 1916 and 30% in 1918. Overall, taxes provided at most 30 percent of national spending. The rest came from borrowing. The national debt jumped from £625 million to £7,800 million. Government bonds usually paid five percent interest. Inflation increased so much that in 1919, a pound bought only a third of what it had bought in 1914. Wages didn't keep up, and the poor and retired people were hit especially hard.

The Royal Family During Wartime

The British royal family faced a big problem during the First World War. This was because they had family ties to the ruling family of Germany, Britain's main enemy. Before the war, the British royal family was known as the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. In 1910, George V became king after his father, Edward VII, died. He ruled throughout the war. He was the first cousin of the German Emperor Wilhelm II, who became a symbol of the war's horrors. Queen Mary, though British like her mother, was the daughter of the Duke of Teck. He was a descendant of the royal House of Württemberg. During the war, H. G. Wells wrote about Britain's "foreign and uninspiring court." King George famously replied: "I may be uninspiring, but I'll be damned if I'm foreign."

To make British people happy, King George changed his family's name to the House of Windsor on July 17, 1917. He chose Windsor as the last name for all of Queen Victoria's descendants living in Britain. This excluded women who married into other families and their children. He and his relatives who were British citizens gave up all their German titles and names. They took on English last names. George gave some of his male relatives British noble titles. For example, his cousin, Prince Louis of Battenberg, became the Marquess of Milford Haven. His brother-in-law, the Duke of Teck, became the Marquess of Cambridge. Others, like Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein and Princess Helena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, simply stopped using their German place names. The way royal family members were titled was also made simpler. Relatives of the British royal family who fought for Germany were cut off. Their British noble titles were suspended by a 1919 order under the Titles Deprivation Act 1917.

Events in Russia created other issues for the monarchy. Tsar Nicholas II of Russia was King George's first cousin, and they looked very much alike. When Nicholas was overthrown in the Russian Revolution of 1917, the new Russian government asked if the tsar and his family could find safety in Britain. The British cabinet agreed, but the king worried that the public would be against it and said no. It's likely the tsar wouldn't have left Russia anyway. He stayed, and in 1918, he and his family were ordered to be killed by Lenin, the Bolshevik leader.

The Prince of Wales—who would later become Edward VIII—really wanted to fight in the war. But the government wouldn't let him. They said it would be too dangerous if the heir to the throne was captured. Despite this, Edward saw trench warfare up close. He tried to visit the front lines as often as he could. For his bravery, he received the Military Cross in 1916. His role in the war, even though limited, made him very popular with war veterans.

Other members of the royal family also helped. The Duke of York (later George VI) joined the Royal Navy. He fought as a turret officer on HMS Collingwood at the Battle of Jutland. But he didn't see any more action in the war, mostly due to poor health. Princess Mary, the King's only daughter, visited hospitals and welfare groups with her mother. She helped with projects to comfort British servicemen and assist their families. One project was Princess Mary's Christmas Gift Fund. Through this, £162,000 worth of gifts were sent to all British soldiers and sailors for Christmas 1914. She actively promoted the Girl Guide movement, the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), and the Land Girls. In 1918, she took a nursing course and worked at Great Ormond Street Hospital.

The Defence of the Realm Act

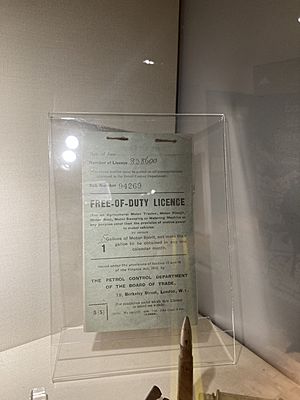

The first Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) was passed on August 8, 1914. This was in the early weeks of the war. Over the next few months, its rules were expanded. It gave the government many new powers. For example, it could take over buildings or land needed for the war effort. Some things the British public were not allowed to do included: hanging around under railway bridges, feeding wild animals, and talking about navy or army matters. British Summer Time was also introduced. Alcoholic drinks were watered down. Pub closing times were moved from 12:30 am to 10 pm. From August 1916, people in London couldn't whistle for a cab between 10 pm and 7 am. DORA was criticized for being too strict and for using the death penalty as a way to stop people from breaking rules. The act itself didn't mention the death penalty. But it allowed civilians who broke these rules to be tried in army courts martial, where the highest punishment was death.

Internment of Foreigners

The Aliens Restriction Act, passed on August 5, required all foreign nationals to register with the police. By September 9, almost 67,000 German, Austrian, and Hungarian citizens had done so. Citizens from enemy countries faced travel restrictions. They couldn't have equipment that might be used for spying. They also had limits on where they could live, especially in areas likely to be invaded. The government didn't want to widely imprison everyone. They changed a military decision from August 7, 1914, which was to imprison all enemy citizens aged 17 to 42. Instead, they focused only on those suspected of being a threat to national security.

By September, 10,500 foreigners were held. But between November 1914 and April 1915, few arrests were made, and thousands were actually released. Public anger against Germans had been growing since October. This was after reports of German cruelties in Belgium. This anger peaked after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania on May 7, 1915. This event caused a week of riots across the country. Almost every German-owned shop had its windows smashed. This reaction forced the government to adopt a tougher policy on internment. This was for the safety of the foreigners themselves, as well as for the country's security. All non-naturalized enemy citizens of military age were to be imprisoned. Those over military age were sent back to their home countries. By 1917, only a small number of enemy citizens were still living freely.

Britain's Armed Forces

The Army's Growth

The British Army during World War I was small compared to other big European countries in 1914. Britain had about 400,000 volunteer soldiers, mostly from English cities. Almost half of them were serving overseas to protect the huge British Empire. For example, in August 1914, 74 out of 157 infantry battalions and 12 out of 31 cavalry regiments were overseas. This number included the Regular Army and reservists in the Territorial Force. Together, they formed the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) for fighting in France. They became known as the Old Contemptibles. The large number of volunteers in 1914–1915, called Kitchener's Army, were meant to fight at the Battle of the Somme. In January 1916, conscription was introduced, first for single men, then for married men in May. By the end of 1918, the army had grown to its largest size of 4.5 million men.

At the start of the war, the Royal Navy was the biggest navy in the world. This was mainly due to the Naval Defence Act 1889 and the "two-power standard". This rule said the navy should have as many battleships as the next two largest navies combined, which were France and Russia at that time.

Most of the Royal Navy's strength was at home in the Grand Fleet. Its main goal was to get the German High Seas Fleet to fight. But a clear victory never happened. The Royal Navy and the German Imperial Navy did meet, especially in the Battle of Heligoland Bight and at the Battle of Jutland. Because they had fewer ships and less firepower, the Germans planned to trap part of the British fleet. They tried this at Jutland in May 1916, but the result was unclear. In August 1916, the High Seas Fleet tried a similar trick and was "lucky to escape being destroyed." The Royal Navy learned important lessons at Jutland, which made it a stronger force later on.

In 1914, the navy also formed the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division from reservists. This division fought a lot in the Mediterranean and on the Western Front. Almost half of the Royal Navy's deaths during the war were from this division, fighting on land, not at sea.

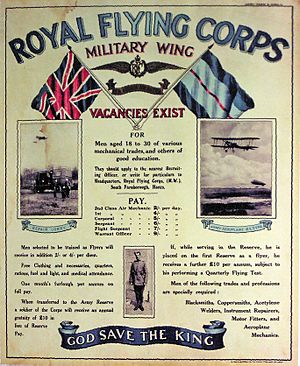

Britain's Air Services

At the start of the war, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), led by David Henderson, was sent to France. It was first used for spotting from the air in September 1914. But it only became good at this when they perfected using wireless communication at Aubers Ridge on May 9, 1915. Aerial photography was tried in 1914, but it also only became effective the next year. In 1915, Hugh Trenchard took over from Henderson, and the RFC became more aggressive. By 1918, photos could be taken from 15,000 feet (4,572 m). Over 3,000 people then interpreted these images. Planes did not carry parachutes until 1918, even though they had been available before the war.

On August 17, 1917, General Jan Smuts gave a report to the War Council about the future of air power. He said that air power could cause "devastation of enemy lands and the destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale." He suggested creating a new air service that would be equal to the army and navy. Forming this new service would make the underused men and machines of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) available for action across the Western Front. It would also end the rivalries between the services that sometimes hurt aircraft buying. On April 1, 1918, the RFC and the RNAS joined together to form a new service, the Royal Air Force (RAF).

Joining the Army and Conscription

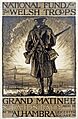

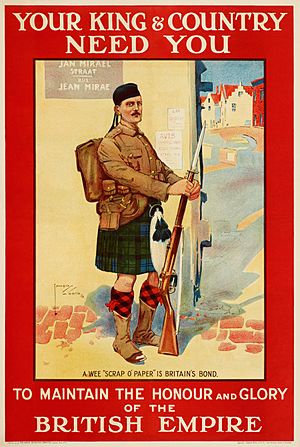

Especially early in the war, many men decided to "join up" the armed forces for various reasons. By September 5, 1914, over 225,000 had signed up to fight for what was called Kitchener's Army. Throughout the war, several things encouraged people to join. These included patriotism, posters from the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, fewer job opportunities, and a desire for adventure to escape boring routines. "Pals battalions," where whole groups were formed from a small area or employer, were also popular. More people joined in England and Scotland. But in Wales and Ireland, political tensions made it harder to get people to enlist.

Recruitment stayed fairly steady through 1914 and early 1915. But it dropped sharply in later years, especially after the Somme campaign, which caused 500,000 casualties. Because of this, conscription was introduced for the first time in January 1916 for single men. It was extended in May–June to all men aged 18 to 41 across England, Wales, and Scotland, through the Military Service Acts.

Cities, with their poverty and unemployment, were good places for the regular British army to find recruits. Dundee, where the jute industry mostly employed women, had one of the highest numbers of reservists and soldiers of any British city. Men hesitated to join because they worried about their families' living standards. Voluntary enlistment rates went up after the government promised a weekly payment for life to the families of men who were killed or disabled. After conscription started in January 1916, every region of the country, except Ireland, was affected.

The policy of relying on volunteers greatly reduced the ability of heavy industry to make the weapons needed for the war. Historian R. J. Q. Adams reported that 19% of men in the iron and steel industry joined the Army. This was 22% of miners, 20% in engineering, 24% in electrical industries, 16% of small arms craftsmen, and 24% of men who made high explosives. In response, important industries were given priority over the army ("reserved occupations"). These included munitions, food production, and merchant shipping.

Conscription Crisis in Ireland (1918)

In April 1918, a law was proposed to extend conscription to Ireland. Although this never actually happened, the effect was "disastrous." Even though many Irish people had volunteered for Irish regiments, the idea of forced conscription was very unpopular. The reaction was especially strong because conscription in Ireland was linked to a promise of "self-government in Ireland." Linking conscription and Home Rule in this way angered the Irish parties in Westminster. They walked out in protest and went back to Ireland to organize opposition. As a result, a general strike was called. On April 23, 1918, work stopped in railways, docks, factories, mills, theaters, cinemas, trams, public services, shipyards, newspapers, shops, and even official munitions factories. The strike was described as "complete and entire, an unprecedented event outside the continental countries." Ultimately, this led to a complete loss of interest in Home Rule. It also caused a loss of public support for the nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party. This party was completely defeated by the separatist republican Sinn Féin party in the December 1918 Irish general election. This was one of the events that led to the Anglo-Irish War.

People Who Refused to Fight

The conscription law allowed people to refuse military service. These were called conscientious objectors. They could be completely excused, do alternative civilian service, or serve as a non-combatant in the army. This depended on how well they could convince a Military Service Tribunal of their reasons. Around 16,500 men were recorded as conscientious objectors, with Quakers playing a big role. About 4,500 objectors were sent to work on farms to do "work of national importance." 7,000 were ordered to do non-combatant duties like carrying stretchers. But 6,000 were forced into the army. When they refused orders, they were sent to prison, like the Richmond Sixteen. About 843 conscientious objectors spent more than two years in prison. Ten died there. Seventeen were first given the death penalty but received life imprisonment instead. 142 were given life sentences. Conscientious objectors who were thought not to have helped the war effort were not allowed to vote for five years after the war.

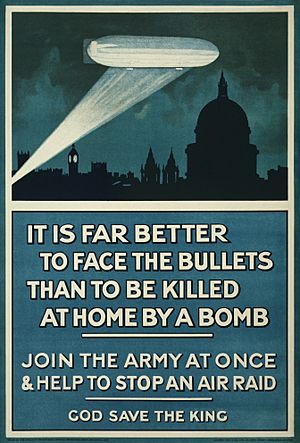

Attacks from Sea and Air

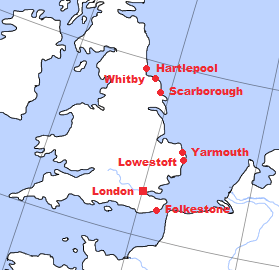

At the start of the First World War, for the first time since the Napoleonic Wars, people in the British Isles were in danger of attacks from naval raids. The country also faced attacks from the air by zeppelins and fixed-wing aircraft. This was also a new experience.

The Raid on Yarmouth happened in November 1914. It was an attack by the German Navy on the British North Sea port and town of Great Yarmouth. Little damage was done to the town itself. Shells only landed on the beach because German ships laying mines offshore were interrupted by British destroyers. One British submarine was sunk by a mine as it tried to leave the harbor and attack the German ships. One German armored cruiser was sunk after hitting two mines outside its own home port.

In December 1914, the German navy attacked the British coastal towns of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby. This attack killed 137 people and injured 593, many of whom were civilians. The attack made the German navy very unpopular with the British public. This was because it was an attack against British civilians in their homes. The British Royal Navy was also criticized for not stopping the raid.

Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft

In April 1916, a German battlecruiser group, with other cruisers and destroyers, attacked the coastal ports of Yarmouth and Lowestoft. These ports had some military importance. But the main goal of the raid was to lure out defending ships. These ships could then be destroyed by the battlecruiser group or by the full High Seas Fleet, which was waiting at sea. The result was unclear. Nearby Royal Navy units were too small to fight, so they mostly stayed away from the German battlecruisers. The German ships left before the first British fast response battlecruiser group or the Grand Fleet could arrive.

Air Attacks

German zeppelins bombed towns on the east coast, starting on January 19, 1915, with Great Yarmouth. London was also hit later that year, on May 31. Propaganda supporting the British war effort often used these raids to their advantage. One recruitment poster claimed: "It is far better to face the bullets than to be killed at home by a bomb." However, the public's reaction was mixed. While 10,000 people visited Scarborough to see the damage, London theaters reported fewer visitors during times of "Zeppelin weather"—dark, clear nights.

Throughout 1917, Germany started using more fixed-wing bombers. The Gotha G.IV's first target was Folkestone on May 25, 1917. After this attack, airship raids quickly decreased. Bomber raids became more common, before Zeppelin raids stopped completely. In total, Zeppelins dropped 6,000 bombs, killing 556 people and injuring 1,357. Soon after the Folkestone raid, bombers started attacking London. One daylight raid on June 13, 1917, by 14 Gothas, killed 162 people in the East End of London. To respond to this new threat, Major General Edward Bailey Ashmore, an RFC pilot, was chosen to create a better system for detecting, communicating, and controlling air defenses. This system, called the Metropolitan Observation Service, covered the London Air Defence Area. It later extended east towards the Kentish and Essex coasts. The Metropolitan Observation Service was fully working until late summer 1918. The last German bombing raid happened on May 19, 1918.

During the war, the Germans carried out 51 airship raids and 52 fixed-wing bomber raids on England. Together, they dropped 280 tons of bombs. These attacks killed 1,413 people and wounded 3,409. Anti-air defense measures had limited success. Of the 397 aircraft that took part in raids, only 24 Gothas were shot down. (Though 37 more were lost in accidents.) This was despite an estimated 14,540 anti-air rounds fired per aircraft. Anti-zeppelin defenses were more successful, with 17 shot down and 21 lost in accidents.

Media and Public Opinion

War Propaganda

Propaganda and censorship were closely connected during the war. The government quickly realized it needed to keep up public morale and fight German propaganda. So, the War Propaganda Bureau was set up in September 1914, led by Charles Masterman. The Bureau hired famous writers like H G Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Rudyard Kipling, as well as newspaper editors. Until it closed in 1917, the department published 300 books and pamphlets in 21 languages. It also sent out over 4,000 propaganda photos every week. Maps, cartoons, and lantern slides were also sent to the media. Masterman also ordered films about the war, such as The Battle of the Somme. This film came out in August 1916, while the battle was still happening. It was meant to boost morale and was generally well-received. The Times reported on August 22, 1916, that:

- Crowded audiences... were interested and thrilled to have the realities of war brought so vividly before them, and if women had sometimes to shut their eyes to escape for a moment from the tragedy of the toll of battle which the film presents, opinion seems to be general that it was wise that the people at home should have this glimpse of what our soldiers are doing and daring and suffering in Picardy.

Media—including newspapers, films, posters, and billboards—were used as propaganda for the public. Those in charge of propaganda preferred using respected upper- and middle-class people to educate the masses. At the time, cinema audiences were mostly working-class men. In contrast, during World War Two, equality was a theme, and class differences were downplayed.

Newspapers and News Magazines

Newspapers during the war had to follow the Defence of the Realm Act. This act eventually had two rules limiting what they could publish. Rule 18 stopped the sharing of sensitive military information, troop movements, and shipping details. Rule 27 made it a crime to "spread false reports," "spread reports that were likely to hurt recruitment," "undermine public trust in banks or money," or cause "disloyalty to His Majesty." When the official Press Bureau failed (it had no legal powers until April 1916), newspaper editors and owners practiced strict self-censorship. Newspaper owners like Viscount Rothermere, Baron Beaverbrook, and Viscount Northcliffe received titles for working with the government. For these reasons, it's believed that censorship had less effect on the British press. It mostly suppressed only socialist journals and briefly the right-wing The Globe. The press was more affected by lower advertising money and higher costs during the war. One big loophole in official censorship was parliamentary privilege. Anything said in Parliament could be reported freely. The most famous act of censorship early in the war was the sinking of HMS Audacious in October 1914. The press was told not to report on the loss, even though passengers on the liner RMS Olympic saw it and American newspapers quickly reported it.

The most popular papers of that time included daily newspapers like The Times, The Daily Telegraph, and The Morning Post. Weekly newspapers like The Graphic and magazines like John Bull were also popular. John Bull claimed to sell 900,000 copies each week. The public's demand for war news led to increased newspaper sales. After the German Navy attacked Hartlepool and Scarborough, the Daily Mail dedicated three full pages to the raid. The Evening News reported that The Times had sold out by 9:15 am, even with higher prices. The Daily Mail itself increased its circulation from 800,000 a day in 1914 to 1.5 million by 1916.

The public's desire for news was partly met by news magazines focused on reporting the war. These included The War Illustrated, The Illustrated War News, and The War Pictorial. They were full of photos and illustrations for all readers. Magazines were made for all social classes and varied in price and tone. Many famous writers contributed to these publications, including H.G. Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Rudyard Kipling. Editorial rules varied. In cheaper publications, it was more important to create patriotism than to give up-to-the-minute news from the front. Stories of German cruelties were common.

War Films and Music

The 1916 British film The Battle of the Somme, made by two official filmmakers, Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell, mixed documentary and propaganda. It aimed to show the public what trench warfare was like. Much of the film was shot on location at the Western Front in France. It had a strong emotional impact. About 20 million people in Britain watched it during its six weeks in cinemas. This made it, as critic Francine Stock said, "one of the most successful films of all time."

On August 13, 1914, the Irish regiment, the Connaught Rangers, were seen singing "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" as they marched through Boulogne. This was reported by the Daily Mail correspondent George Curnock on August 18, 1914. Other units of the British Army then picked up the song. In November 1914, the famous music hall singer Florrie Forde sang it in a pantomime. This helped the song become popular worldwide. Another song from 1916, "Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit-Bag," also became very popular as a music hall and marching song. It helped boost British morale despite the war's horrors.

War Poems

There was also a notable group of war poets who wrote about their own experiences of war. Their poems captured public attention. Some died while serving, most famously Rupert Brooke, Isaac Rosenberg, and Wilfred Owen. Others, like Siegfried Sassoon, survived. The poems often focused on the youth or innocence of the soldiers. They also showed the brave way soldiers fought and died. This is clear in lines like "They fell with their faces to the foe," from the "Ode of Remembrance" by Laurence Binyon's For the Fallen. This poem was first published in The Times in September 1914. Female poets like Vera Brittain also wrote from the home front. They mourned the loss of brothers and lovers fighting at the front.

Economic Changes During the War

Overall, Britain managed the war's finances well. There was no plan before the war for how to use economic resources. Controls were put in place slowly, as new urgent needs came up. Since the City of London was the world's financial center, it was possible to handle money smoothly. In total, Britain spent £4 million every day on the war effort.

The economy (measured by GDP) grew about 14% from 1914 to 1918. This happened even though many men were in the military. In contrast, the German economy shrank by 27%. The war led to less civilian spending, with a big shift towards making weapons. The government's share of GDP jumped from 8% in 1913 to 38% in 1918. (For comparison, it was 50% in 1943.) The war forced Britain to use up its financial savings. It also had to borrow large amounts from private and government lenders in the United States. Shipments of American raw materials and food allowed Britain to feed itself and its army while keeping up production. The financing was generally successful. London's strong financial position reduced the harmful effects of inflation, unlike the much worse conditions in Germany. Overall, consumer spending dropped 18% from 1914 to 1919. Women were available, and many worked in munitions factories and other home front jobs that men had left.

Scotland focused on providing soldiers, ships, machinery, food (especially fish), and money. Its shipbuilding industry grew by a third.

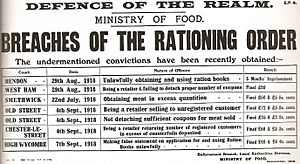

Food Rationing

At first, the government didn't want to control food markets. This was part of its "business as usual" policy. It resisted efforts to set minimum prices for grain production. But it did give in on controlling essential imports like sugar, meat, and grains. When changes were introduced, they had limited effect. In 1916, it became illegal to eat more than two courses for lunch in a public place, or more than three for dinner. Fines were introduced for people caught feeding pigeons or stray animals.

In January 1917, Germany started using U-boats (submarines) to sink Allied and neutral ships bringing food to Britain. This was an attempt to starve Britain into defeat under their unrestricted submarine warfare program. One response was to introduce voluntary rationing in February 1917. The King and Queen themselves promoted this sacrifice. Bread was subsidized from September that year. Local authorities started taking action on their own. So, compulsory rationing was introduced in stages between December 1917 and February 1918. This happened as Britain's wheat supplies dropped to only six weeks' worth. For the most part, rationing improved the country's health. This was because it balanced the consumption of essential foods. To manage rationing, ration books were introduced on July 15, 1918, for butter, margarine, lard, meat, and sugar. During the war, the average calorie intake only dropped three percent, but protein intake dropped six percent.

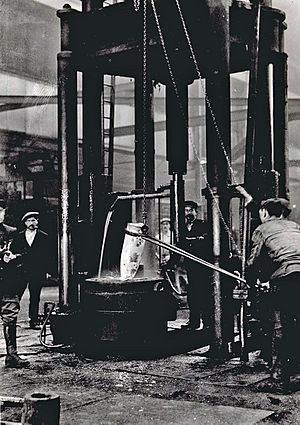

Industry and Production

Overall British production fell by ten percent during the war. However, some industries, like steel, saw increases. Britain faced a big problem called the Shell Crisis of 1915. There were severe shortages of artillery shells on the Western Front. New leadership was needed. In 1915, a powerful new Ministry of Munitions was formed under David Lloyd George to control weapons production.

The government's policy, according to historian and Conservative politician J. A. R. Marriott, was that:

- No private interest was to be permitted to obstruct the service, or imperil the safety, of the State. Trade Union regulations must be suspended; employers' profits must be limited, skilled men must fight, if not in the trenches, in the factories; man-power must be economized by the dilution of labour and the employment of women; private factories must pass under the control of the State, and new national factories be set up. Results justified the new policy: the output was prodigious; the goods were at last delivered.

By April 1915, only two million shells had been sent to France. By the end of the war, this number reached 187 million. By 1918, a year's worth of pre-war light weapons production could be done in just four days. Aircraft production in 1914 employed 60,000 men and women. By 1918, British companies employed over 347,000 people.

Workers and Trade Unions

Making weapons in factories was a key part of the war. With a third of the male workforce joining the military, there was a very high demand for factory workers. Many women were hired temporarily. Most trade unions strongly supported the war effort. They reduced strikes and old work rules. However, coal miners and engineers were less enthusiastic. Trade unions were encouraged, and their membership grew from 4.1 million in 1914 to 6.5 million in 1918. It peaked at 8.3 million in 1920 before falling to 5.4 million in 1923. In 1914, 65% of union members were part of the Trades Union Congress (TUC). This rose to 77% in 1920. Women were reluctantly allowed to join trade unions. Looking at a union of unskilled workers, Cathy Hunt concluded that its view of women workers "was at best inconsistent and at worst aimed almost entirely at improving and protecting working conditions for its male members." Labour's reputation had never been higher, and it systematically placed its leaders into Parliament.

The Munitions of War Act 1915 followed the Shell Crisis of 1915. This was when the supply of materials to the front became a political issue. The Act banned strikes and lockouts. Instead, it made disagreements go to compulsory arbitration. It set up a system to control war industries. It also created munitions tribunals, which were special courts to enforce good working practices. It temporarily stopped restrictive practices by trade unions. It tried to control how workers moved between jobs. The courts ruled that the definition of munitions was wide enough to include textile workers and dock workers. The 1915 act was canceled in 1919. But similar laws were used during the Second World War.

It wasn't until December 1917 that a War Cabinet Committee on Manpower was created. The British government avoided forcing people to work in specific jobs. (Though 388 men were moved as part of the voluntary National Service Scheme.) Belgian refugees became workers, but they were often seen as "job stealers." Also, using Irish workers, who were exempt from conscription, caused more resentment. Workers in some areas went on strike action because they worried about the "dilution of labour." This was caused by bringing outside groups into the main workforce. The efficiency of major industries greatly improved during the war. For example, the Singer Clydebank sewing machine factory received over 5,000 government contracts. It made 303 million artillery shells, shell parts, fuzes, and airplane parts. It also made grenades, rifle parts, and 361,000 horseshoes. By the end of the war, about 70 percent of its 14,000 workers were women.

Energy Supply

Energy was very important for Britain's war effort. Most energy came from coal mines in Britain, where the main issue was having enough workers. However, the flow of oil for ships, lorries, and industrial use was critical. There were no oil wells in Britain, so all oil was imported. The U.S. produced two-thirds of the world's oil. In 1917, Britain used 827 million barrels of oil. Of this, 85 percent came from the United States, and 6 percent from Mexico. The big problem in 1917 was how many oil tankers would survive the German U-boats. Convoys (groups of ships traveling together) and building new tankers solved the German threat. Strict government controls made sure all essential needs were met. An Inter-Allied Petroleum Conference assigned American oil supplies to Britain, France, and Italy.

Fuel oil for the Royal Navy was the highest priority. In 1917, the Royal Navy used 12,500 tons of oil a month. But it had a supply of 30,000 tons a month from the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, using their oil wells in Persia.

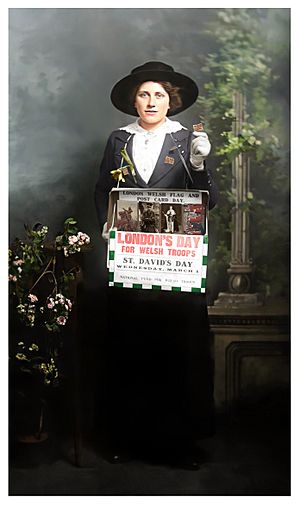

Social Changes in Britain

Throughout the war, Britain faced a serious shortage of able-bodied men ("manpower"). Women were needed to take on many jobs traditionally done by men. This was especially true in arms manufacturing. However, this only became very important in the later years of the war. This was because unemployed men were often given priority by employers at first. Women found work in munitions factories (as "munitionettes") despite initial opposition from trade unions. This directly helped the war effort. They also worked in the Civil Service, taking men's jobs and freeing them for the front. The number of women employed by the service grew from 33,000 in 1911 to over 102,000 by 1921. The total increase in female employment is estimated at 1.4 million, from 5.9 to 7.3 million. Female trade union membership increased from 357,000 in 1914 to over a million by 1918—a 160 percent increase. Beckett suggests that most of these were working-class women starting work at a younger age than they would have otherwise. Or they were married women returning to work. This, along with the fact that only 23 percent of women in the munitions industry were actually doing men's jobs, would greatly limit the war's overall impact on the long-term future of working women.

Early in the war, the government focused on women extending their existing roles. For example, helping Belgian refugees. But also on getting more men to join the army. They did this through the "Order of the White Feather" and by promising home comforts for the men at the front. In February 1916, groups were set up, and a campaign started to get women to help in agriculture. In March 1917, the Women's Land Army was created. One goal was to attract middle-class women to be examples of patriotic involvement in new types of jobs. However, the Women's Land Army uniform included male overalls and trousers. This caused debate about whether such clothing was proper. The government responded by using language that made the new roles seem more feminine. In 1918, the Board of Trade estimated that 148,000 women worked in agriculture. Though a figure of nearly 260,000 has also been suggested.

The war also caused a split in the British suffragette movement. The main group, led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel's Women's Social and Political Union, stopped their campaign for the war's duration. In contrast, more radical suffragettes, like the Women's Suffrage Federation run by Emmeline's other daughter, Sylvia, continued their (sometimes violent) fight. Women were also allowed to join the armed forces in non-fighting roles. By the end of the War, 80,000 women had joined the armed forces in support roles like nursing and cooking.

After the war, millions of returning soldiers still couldn't vote. This was a problem for politicians. They seemed to be denying the vote to the very men who had fought to protect Britain's democratic system. The Representation of the People Act 1918 tried to solve this. It gave all adult men the right to vote, as long as they were over 21 and owned a home. It also gave the vote to women over 30 who met certain property requirements. Giving this group of women the vote was seen as a way to recognize their help as defense workers. However, what Members of Parliament (MPs) truly felt at the time is debated. In the same year, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 allowed women over 21 to become MPs.

The new government in 1918 aimed to create a "land fit for heroes." This phrase came from a speech by David Lloyd George in Wolverhampton on November 23, 1918. He said, "What is our task? To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in." More generally, the war has been seen as removing some of the social barriers that existed in Victorian and Edwardian Britain.

Conditions Across British Regions

Stephen Badsey says that in 1914, Great Britain (not including Ireland) was the most similar and stable society among the major powers. He states that almost everyone could read and spoke English as their first language. Christianity was almost universal, and religious discrimination was limited. The unique cultures of Scotland and Wales were accepted but often overlooked in the language of the time. He also argues that:

This homogeneity was strengthened rather than weakened by a marked parochialism and regionalism, of which the Scots and Welsh identities were only the most prominent, with most people looking to their local rather than national leaders, including local business, religious, and trade union representatives.

The War deeply affected rural areas. The U-boat blockade meant the government had to take full control of the food supply and farm workers. Grain production was a high priority. The Corn Production Act 1917 guaranteed prices, set wage rates, and required farmers to be efficient. The government strongly encouraged turning unused land into farmland. The Women's Land Army brought in 23,000 young women from towns and cities. They milked cows, picked fruit, and replaced men who joined the military. More use of tractors and machinery also replaced farm laborers. However, by late 1915, there was a shortage of both men and horses on farms. County War Agricultural Executive Committees reported that taking men away continued to hurt food production. This was because farmers believed a certain number of men and horses were needed to run a farm.

Kenneth Morgan argues that "the overwhelming mass of the Welsh people put aside their political and industrial differences and threw themselves into the war with gusto." Intellectuals and ministers actively promoted the war spirit. At first, early recruitment rates were somewhat lower than in English cities with smaller populations. Later, with 280,000 men joining the services (14% of the population), Wales's effort was greater than both England and Scotland. Adrian Gregory points out that Welsh coal miners, while officially supporting the war, refused the government's request to cut short their holiday time. After some discussion, the miners agreed to work longer days.

Scotland's unique features have drawn much attention from scholars. Daniel Coetzee shows it supported the war effort with widespread enthusiasm. It especially provided soldiers, ships, machinery, food (particularly fish), and money, engaging with the conflict with some enthusiasm. With a population of 4.8 million in 1911, Scotland sent 690,000 men to the war. Of these, 74,000 died in combat or from disease, and 150,000 were seriously wounded. Scottish cities, with their poverty and unemployment, were favorite places for the regular British army to recruit. Dundee, where the jute industry mostly employed women, had one of the highest numbers of reservists and serving soldiers of almost any British city. Men hesitated to enlist because they worried about their families' living standards. Voluntary enlistment rates went up after the government promised a weekly payment for life to the families of men who were killed or disabled. After conscription started in January 1916, every part of the country was affected. Sometimes Scottish troops made up a large part of the active fighters. They suffered many losses, as at the Battle of Loos, where there were three full Scots divisions and other Scottish units. So, even though Scots were only 10 percent of the British population, they made up 15 percent of the national armed forces. They eventually accounted for 20 percent of the dead. Some areas, like the sparsely populated Island of Lewis and Harris, suffered some of the highest proportional losses of any part of Britain. Clydeside shipyards and the nearby engineering shops were the main centers of war industry in Scotland. In Glasgow, radical protests led to industrial and political unrest that continued after the war ended.

War Casualties

In a post-war report called Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War 1914–1920 (The War Office, March 1922), the official numbers list 908,371 'soldiers' as either killed in action, dying of wounds, dying as prisoners of war, or missing in action in the World War. (This breaks down to: Britain and its colonies 704,121; British India 64,449; Canada 56,639; Australia 59,330; New Zealand 16,711; South Africa 7,121.) Listed separately were the Royal Navy (including the Royal Naval Air Service until March 31, 1918) war dead and missing of 32,287, and the Merchant Navy war dead of 14,661. The numbers for the Royal Flying Corps and the new Royal Air Force were not given in this report.

A second book, Casualties and Medical Statistics (1931), the final part of the Official Medical History of the War, gives British Empire Army losses by cause of death. The total combat losses from 1914 to 1918 were 876,084. This included 418,361 killed, 167,172 died of wounds, 113,173 died of disease or injury, 161,046 missing and presumed dead, and 16,332 died as prisoners of war.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission lists 888,246 imperial war dead (not including the dominions, which are listed separately). This number includes identified burials and those remembered by name on memorials. There are an additional 187,644 unidentified burials from the Empire as a whole.

The civilian death rate was 292,000 higher than before the war. This included 109,000 deaths due to food shortages and 183,577 from Spanish flu. The 1922 War Office report detailed the deaths of 1,260 civilians and 310 military personnel due to air and sea attacks on the home islands. Losses at sea included 908 civilians and 63 fishermen killed by U-boat attacks.

With a population of 4.8 million in 1911, Scotland sent 690,000 men to the war. Of these, 74,000 died in combat or from disease, and 150,000 were seriously wounded. Sometimes Scottish troops made up a large part of the active fighters. They suffered many losses, as at the Battle of Loos, where there were three full Scots divisions and other Scottish units. So, even though Scots were only 10 percent of the British population, they made up 15 percent of the national armed forces. They eventually accounted for 20 percent of the dead. Some areas, like the sparsely populated Island of Lewis and Harris, suffered some of the highest proportional losses of any part of Britain. Clydeside shipyards and the engineering shops of west-central Scotland became the most important center for shipbuilding and arms production in the Empire. In the Lowlands, especially Glasgow, poor working and living conditions led to industrial and political unrest.

The War's Impact and Memory

Immediate Aftermath of the War

Images of trench warfare became powerful symbols of human suffering and strength. After the war, many veterans were injured or suffered from shell shock. In 1921, 1,187,450 men received pensions for war disabilities. A fifth of these had lost limbs or eyesight, or suffered paralysis or mental illness.

The war was a huge economic disaster. Britain went from being the world's biggest investor in other countries to its biggest debtor. Interest payments took up about 40 percent of the national budget. Inflation more than doubled between 1914 and its peak in 1920. The value of the British Pound fell by 61.2 percent. Payments from Germany in the form of free coal hurt the local coal industry. This helped cause the 1926 General Strike. During the war, British private investments abroad were sold, raising £550 million. However, £250 million in new investments also happened during the war. So, the net financial loss was about £300 million. This was less than two years of investment compared to the pre-war average. This loss was more than made up for by 1928. Material loss was "slight." The most significant loss was 40 percent of the British merchant fleet, sunk by German U-boats. Most of this was replaced in 1918 and immediately after the war. The military historian Correlli Barnett has argued that "in objective truth the Great War in no way inflicted crippling economic damage on Britain." But he said the war only "crippled the British psychologically" (emphasis in original).

Less clear changes include the growing confidence of the Dominions within the British Empire. Battles like Gallipoli for Australia and New Zealand, and Vimy Ridge for Canada, led to increased national pride. This made them less willing to remain under London's control. These battles were often shown positively in these nations' propaganda. They symbolized their power during the war. The war also brought out strong local nationalism. People tried to use the idea of self-determination (nations deciding their own future) that was being used in Eastern Europe. Britain faced unrest in Ireland (1919–21), India (1919), Egypt (1919–23), Palestine (1920–21), and Iraq (1920). This happened when they were supposed to be reducing their military. However, Britain's only loss of territory was in Ireland. The delay in solving the home rule issue, along with the 1916 Easter Rising, and a failed attempt to introduce conscription in Ireland, increased support for radical separatists. This indirectly led to the start of the Irish War of Independence in 1919.

Further change came in 1919. With the Treaty of Versailles, London took control of an additional 1,800,000 square miles (4,661,970 km2) and 13 million new people. The colonies of Germany and the Ottoman Empire were given to the Allies (including Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa) as League of Nations mandates. Britain gained control of Palestine and Transjordan, Iraq, parts of Cameroon and Togo, and Tanganyika. Indeed, the British Empire reached its largest size after this settlement.

How the War is Remembered

The horrors of the Western Front, as well as Gallipoli and Mesopotamia, were deeply burned into the minds of the 20th century. To a large extent, how the war is understood in popular culture focuses on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Historian A. J. P. Taylor argued, "The Somme set the picture by which future generations saw the First World War: brave helpless soldiers; blundering obstinate generals; nothing achieved." A similar view of the war's cultural impact has been argued by historian Adrian Gregory:

- "The verdict of popular culture is more or less unanimous. The First World War was stupid, tragic and futile. The stupidity of the war has been a theme of growing strength since the 1920s."

However, many historians do not believe this view of the conflict is correct. They argue instead that the Central Powers were the main attackers and that Germany was a threat to Britain and Europe.

A poll by Yougov in 2014 suggested that 58% of modern British adults believed the Central powers were mainly responsible for the start of the First World War. 3% blamed the Triple Entente (the main countries in each group were listed), 17% blamed both sides, and 3% said they didn't know. 52% believed generals had failed British soldiers, 17% believed they had done as well as they could, while 30% said they didn't know or believed neither statement. 40% believed the conflict was a Just War from a British perspective, while 27% believed there was no difference between the participants. 34% believed Britain's participation in the First World War was something to be proud of, while 15% believed it was something to regret. A report on war commemorations by a think tank, which researched public attitudes in 2013, argued that public knowledge of the First World War was quite limited:

Over half of men – 58% – knew that the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand sparked the first world war, but barely a third of women – 39% – gave the correct answer. Bucking a trend seen elsewhere in the polling, 18–24-year-olds did reasonably well on this question, with 52% answering correctly. That said, 4% of this age group believed the assassination of Abraham Lincoln was the trigger for the war. There was a similar lack of clarity around the other key figures of the war. When asked who was the British prime minister at the war’s start, fewer than one in ten were able to identify Herbert Asquith. Astonishingly, 7% of 18–24-year-olds believed Margaret Thatcher was resident at 10 Downing Street in 1918. Conversely, there was more certainty about the leadership of Germany during the war, with nearly a third recognising Kaiser Wilhelm II. As British Future’s research groups also discovered, many find it difficult to distinguish between the first and second world wars. A clear indication of this came when people were asked “the invasion of which territory sparked Britain’s declaration of war?”. While nearly one in five answered Poland, the second most popular answer after “don’t know”, only 13% correctly identified Belgium. While the conflation of the two wars may excuse some of the answers given, it appears that lack of knowledge is the key factor. This is most telling when respondents were asked whether particular countries were Britain’s allies or enemies during the war, or whether they were neutral. While we may expect people to struggle with countries like Bulgaria or Japan, there is a certain folklore to Britain’s relationship with Germany. Despite this, a mere 81% identified Germany as an enemy during the first world war, falling to three quarters (75%) of women and just over two thirds (69%) of 18–24-year-olds. The consequences of the war for the homefront were no clearer for most of those polled. Only 13% correctly identified 1916 as the year conscription was introduced, while fewer than one in 10 – just 7% – knew that women were first entitled to vote in 1918.

Images for kids

See also

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- British home army in the First World War

- Imperial German plans for the invasion of the United Kingdom

- Opposition to World War I

- The Women's Peace Crusade

- British Land Units of the First World War