Interwar Britain facts for kids

| 11 November 1918 – 3 September 1939 | |

| Preceded by | First World War |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Second World War |

| Monarch | |

| Leader(s) | |

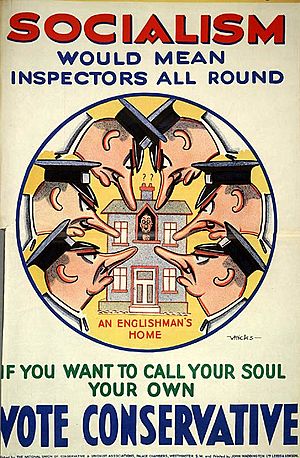

The time between the First World War and the Second World War in the United Kingdom (from 1918 to 1939) is called the interwar period. After the Partition of Ireland, Britain became more stable. However, it also faced tough economic times. In politics, the old Liberal Party lost its power. The Labour Party grew to become the main rival to the strong Conservative Party.

Even though the Great Depression affected many countries badly, Britain didn't suffer as much economically or politically. Still, some areas, like mining towns and parts of Scotland and North West England, had very high unemployment and hardship for a long time. During this period, British society changed a lot. Workers became more aware of their rights, leading to the rise of the Labour Party. Women also gained the right to vote, and the government started more social reforms. People began to question old traditions and class differences became less strict.

Contents

- Britain's Political Journey (1918-1939)

- Lloyd George's Government: 1918–1922

- A Time of Change: 1922–1924

- Britain's First Labour Government: 1924

- Conservative Government: 1924–1929

- Second Labour Government: 1929–1931

- National Government: 1931–1939

- Growing the Welfare State

- King George V's Reign

- The British Empire and Commonwealth

- Britain's Foreign Policy (1919-1939)

- Britain's Economy (1918-1939)

- Society and Culture in Interwar Britain

Britain's Political Journey (1918-1939)

Lloyd George's Government: 1918–1922

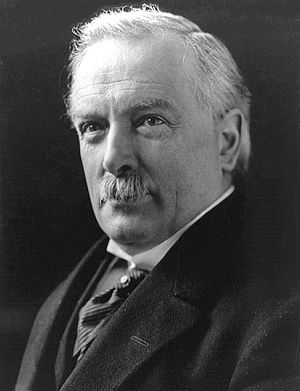

After the First World War ended in 1918, a big election was held. David Lloyd George led a coalition government and won by a landslide. He promised to make Britain "a fit country for heroes to live in." Most of the politicians in his government were Conservative. This election also showed the decline of the Liberal Party and the growing strength of the Labour Party.

After the war, many rules that controlled industries and prices were removed. However, food rationing stayed until 1921. Prices and wages went up quickly in 1919. People worried about the government spending too much money. A group called the Anti-Waste League gained support by attacking "wasteful" public spending. In 1922, a report suggested cutting money for the armed forces and social services. These cuts, known as the "Geddes Axe", and the end of the post-war economic boom, made it hard for the government to keep its promises of rebuilding the country.

More People Get to Vote

The Representation of the People Act 1918 was a huge step for democracy in Britain. It allowed all men aged 21 and older to vote, no matter how much property they owned. Even more importantly, it gave most women over 30 the right to vote. By 1928, all women could vote on the same terms as men.

Some people worried about revolutions, like those happening in Russia and Germany. However, the Labour Party, which represented working-class people, supported the government and was against violent revolution. The King, George V, and his advisors were also concerned about the monarchy's future. To connect better with ordinary people, King George V started visiting shipyards and factories. He talked to workers and praised their efforts. He also became friendly with Labour Party leaders. This made the royal family more popular and helped them connect with people from all walks of life. For example, in 1924, when no party had a clear majority, the King allowed Ramsay MacDonald to become the first Labour Prime Minister. This helped ease worries about the Labour Party.

Ireland's Independence

In 1916, there was an uprising in Dublin by Irish republicans called the Easter Rising. It was quickly stopped by the British Army. The British government responded harshly, arresting many people and executing leaders. This made many Irish Catholics want independence even more.

In 1918, the Sinn Féin party, which wanted full independence, won most of the Irish seats in the British Parliament. Instead of taking their seats, they set up their own parliament in Dublin and declared an Irish Republic. This led to the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921). Britain sent soldiers and special police units, like the "Black and Tans", to fight the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The IRA used clever tactics, like assassinating British intelligence leaders, to fight back.

Finally, in 1920, the Government of Ireland Act 1920 divided Ireland into Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland. In 1921, Sinn Féin leaders in the south agreed to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. This led to Southern Ireland becoming the Irish Free State in 1922, which was mostly independent. Northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom. This settled the Irish situation for a while, though some disagreements continued for decades.

A Time of Change: 1922–1924

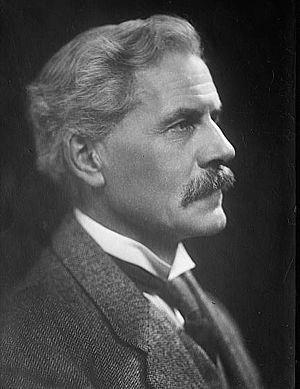

In 1922, Lloyd George's government ended. Bonar Law became the new Conservative Prime Minister. He promised to cut spending and avoid interfering in other countries' affairs. He won the 1922 election. However, he resigned in 1923 due to illness, and Stanley Baldwin took over.

Baldwin became a very important figure in British politics. He led the Conservative Party and was Prime Minister multiple times. He combined social reforms with stable government, which was popular with voters. His goal was to make people choose between the Conservatives (right) and Labour (left), pushing out the Liberals in the middle. This worked, and the Liberals lost many seats.

Baldwin called an election in 1923, hoping to get support for new taxes on imported goods, which he thought would help unemployment. However, this plan backfired. He lost many seats to the Labour and Liberal parties, who supported free trade. The Conservatives were still the largest party, but they didn't have a clear majority. In January 1924, Labour and the Liberals voted against Baldwin's government, and he resigned. The next day, Ramsay MacDonald formed Britain's first Labour government.

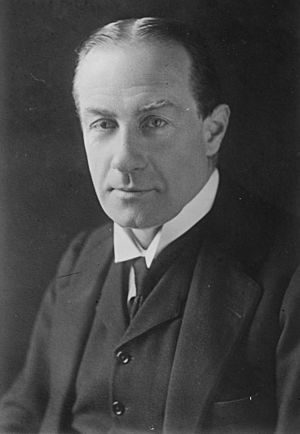

Britain's First Labour Government: 1924

Even though the Labour government didn't have a majority, it passed important laws. The Housing (Financial Provisions) Act 1924 increased government money for local councils to build homes for low-paid workers. The finance minister, Philip Snowden, balanced the budget by cutting spending and taxes.

The Labour government officially recognized the Soviet Union in 1924. They tried to settle old debts from before the Russian Revolution. However, the Soviets wanted a loan from the British government first. This caused arguments, and the Conservatives and Liberals criticized the agreements.

A newspaper called Workers' Weekly, linked to the Communist Party, published an article that led to an arrest. The Labour government later dropped the case, which was seen as political interference by other parties. Just before an election in 1924, a letter, now believed to be fake, was published. It was called the "Zinoviev letter" and seemed to be from a Soviet official, telling British communists to cause trouble. This letter, along with other issues, hurt the Labour Party.

In the election, the Liberals lost many seats, mostly to the Conservatives. Labour also lost seats. The Conservatives won a large majority, and Stanley Baldwin became Prime Minister again.

Conservative Government: 1924–1929

The Conservative government wanted peace at home and abroad. They hoped to fix problems left by the war and return to how things were before. The Locarno Treaties in 1925 aimed to bring France and Germany closer, which people hoped would lead to lasting peace. Britain also returned to the gold standard in 1925, hoping it would bring back prosperity.

The government tried to reduce conflict between social classes and improve living conditions. They expanded social services like unemployment benefits and old age pensions. However, they couldn't stop the general strike in May 1926, which lasted nine days. After this strike, there were fewer strikes, and trade union membership went down.

In the 1929 election, Baldwin's party campaigned on "Safety First," but the result was a "hung parliament," meaning no party had a clear majority. Labour became the largest party. Baldwin resigned, and Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister again, leading the second Labour government.

Second Labour Government: 1929–1931

This Labour government passed the Coal Mines Act 1930, which shortened miners' working days and allowed mine owners to set prices. The Housing Act 1930 led to more slum clearances, building new homes for people.

Then came the Wall Street Crash of 1929 in the United States, which started the Great Depression. By 1930, over two million people in Britain were unemployed. Exports dropped by half. In 1931, a report suggested cutting public spending and raising taxes to fix the government's financial problems. Bankers advised cutting unemployment benefits to restore confidence in the British currency.

The Labour government couldn't agree on these cuts. So, on August 24, MacDonald formed a new National Government with the Conservatives and some Liberals. The Labour Party opposed this coalition and saw MacDonald as a "traitor."

National Government: 1931–1939

The National Government quickly got loans from banks in Paris and New York. The finance minister, Philip Snowden, presented a budget that cut spending and raised taxes. However, people continued to withdraw money from British banks, especially after news of a naval mutiny in September 1931. This forced Britain to abandon the gold standard.

In the 1931 election, MacDonald asked the country to give the National Government a "doctor's mandate" to fix the crisis. The National Government won a huge victory, and the Labour Party was left with very few politicians.

The Conservatives, who were the main part of the National Government, wanted to use tariffs (taxes on imported goods) to help the economy. They passed laws to tax foreign goods and protect British industries. This change from free trade caused some Liberals to leave the government.

The government also passed the Special Areas Act 1934, which gave money to "distressed areas" like South Wales and Scotland that were hit hardest by unemployment.

As German rearmament grew under Adolf Hitler, the National Government started its own rearmament programme in 1934. However, many people in Britain still wanted peace and disarmament. The Labour and Liberal parties were against rearmament, preferring to work through the League of Nations. Winston Churchill, who was not in the government, was one of the few who strongly pushed for more weapons.

In 1935, the government announced increased spending on the armed forces. Stanley Baldwin became Prime Minister again and called an election. He said there would be "no great armaments" but sought support for rearmament. The National Government won, though with a smaller majority.

In late 1936, King Edward VIII wanted to marry a divorced woman, Wallis Simpson. As head of the Church of England, the King couldn't marry a divorced person. The government opposed the marriage. Edward decided to give up his throne. This was announced on December 10 and made law the next day.

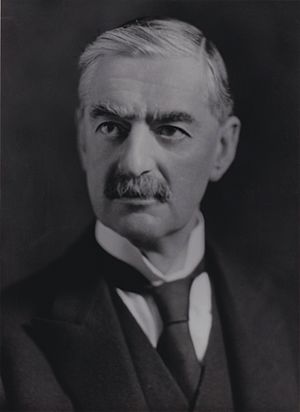

On May 28, 1937, Neville Chamberlain replaced Baldwin as Prime Minister. He started new social reforms. The Special Areas (Amendment) Act 1937 offered tax breaks to businesses that set up in high-unemployment areas. The government also took control of coal mining royalties in 1938, a step towards nationalizing the mines later. More workers gained the right to a paid annual holiday, and the school leaving age was raised to 15.

However, Chamberlain's time as Prime Minister was dominated by Hitler's actions. Chamberlain tried to deal with Hitler through appeasement, which meant giving in to some of Germany's demands, while also rearming Britain. The most famous example was the Munich Agreement in 1938, where Britain and France allowed Germany to take parts of Czechoslovakia. But in March 1939, Hitler took over all of Czechoslovakia, breaking his promise. British opinion was shocked. On March 31, Chamberlain promised to protect Poland. Britain also started peacetime conscription for the first time. After Germany signed a deal with the Soviet Union, Britain made an alliance with Poland. On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain and France declared war, starting the Second World War.

Growing the Welfare State

After the war, two big programs dealing with unemployment and housing were passed. These greatly expanded the welfare state, which helps people in need.

The Unemployment Insurance Act 1920 created a system that provided weekly payments to almost all unemployed workers. It was funded by contributions from both employers and workers. This system helped many people, especially when unemployment rose in 1921. The government continued to expand unemployment help, covering more workers over time. For those who used up their benefits, a "means test" was introduced to check if they still needed help.

Neville Chamberlain also changed how poor relief was managed, transferring control of hospitals to local authorities. The number of workers covered by health insurance, which provided sickness benefits and medical treatment, also increased. By 1939, Britain's social services were considered among the most advanced in the world.

Better Homes for Families

Building new homes was a big success story between the wars. The number of homes in England and Wales grew from 7.6 million in 1911 to 11.3 million in 1939.

The Housing, Town Planning, &c. Act 1919, also known as the "Addison Act," set up a system for local councils to build homes. It required them to check housing needs and build new houses to replace old, rundown slums. The government helped pay for low rents. These new homes often had modern features like indoor toilets, bathrooms, and electric lighting. By 1938, council housing made up 10% of all homes in Britain.

During this time, suburbs grew rapidly around cities. By 1939, over 4 million new suburban homes had been built. Britain went from being the most urbanized country to the most suburbanized. More people, even working-class families, started to own their own homes. Home ownership rates rose from 15% before 1914 to 32% by 1938. This boom was largely funded by people's savings in building societies, which offered easier mortgage terms.

King George V's Reign

King George V (who ruled from 1910 to 1936) was a respected monarch. He was seen as hardworking and was admired across Britain and its Empire. He set the standard for how British royalty should act, focusing on middle-class values rather than extravagant lifestyles. He was neutral and fair, often acting as a mediator. For example, in 1921, he helped end the Irish war of independence by encouraging a truce. Historians praise his efforts as a great service to Britain. His strong sense of duty and fairness made him popular and prevented politicians from using him for their own gain.

The King's popularity grew during the First World War when he visited many hospitals, factories, and military bases. This helped boost the morale of ordinary workers and soldiers. In 1932, George V started the Royal Christmas speech on the radio, which became a popular tradition across the British Empire every year. His Silver Jubilee in 1935 was a huge national celebration. His funeral and memorials were also grand events that showed how the role of royalty was changing in a more democratic nation. The monarchy became stronger, and national unity grew during this time.

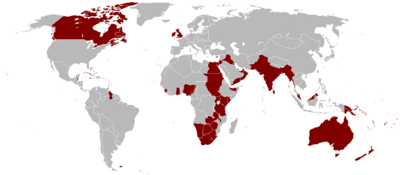

The British Empire and Commonwealth

After gaining control of some German and Ottoman territories in 1919, the British Empire reached its largest size. During the interwar years, there were many efforts to develop the colonies economically and educationally. The Dominions (like Canada, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand) were prosperous and mostly managed themselves. The most challenging areas for Britain were India and Palestine.

The Dominions became almost fully independent in foreign policy with the Statute of Westminster 1931. However, they still relied on Britain for naval protection. After 1931, trade policy favored Imperial Preference, meaning lower tariffs (taxes) on goods from within the British Commonwealth compared to those from outside.

In India, nationalist groups like the Indian National Congress, led by Mahatma Gandhi, pushed for independence. India had helped Britain a lot in the First World War, but was disappointed by the limited self-rule offered in 1919. Tensions grew, leading to events like the Amritsar Massacre. Gandhi developed his method of nonviolent resistance. Despite many talks in the 1930s, a strong group in Britain, led by Winston Churchill, blocked reforms that would satisfy Indian nationalists. The Government of India Act 1935 tried to create a system that would keep British control. The Labour Party supported Indian independence, and after 1945, they were able to grant it.

Egypt became a British protectorate in 1914 and gained formal independence in 1922, though it remained closely linked to Britain. British troops stayed to guard the Suez Canal. Iraq, which was a British mandate since 1920, also became independent in 1932, but Britain still guided its foreign and defense policies.

In Palestine, Britain had to deal with conflicts between Arabs and a growing number of Jewish immigrants. The Balfour Declaration promised a national home for Jewish people in Palestine. As more Jews arrived, the Arab population revolted in 1936. As war with Germany seemed likely, Britain decided that Arab support was more important. They limited Jewish immigration, which then led to a Jewish uprising.

Dominions Take Control of Foreign Policy

In 1922, when Britain faced a crisis with Turkey, Prime Minister Lloyd George asked the Dominions for military help. They refused. The First World War had made the Dominions feel more independent and confident. They were already members of the League of Nations and didn't want to automatically follow Britain's lead.

The right of the Dominions to have their own foreign policy was recognized at the 1923 Imperial Conference. The 1926 Imperial Conference issued the Balfour Declaration of 1926, which stated that the Dominions were "autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status." This was made legal by the Statute of Westminster 1931. India, however, did not get this status, and its foreign policy was still decided by London.

Newfoundland faced severe economic problems during the Great Depression and chose to become a British colony again until it joined Canada in 1948. The Irish Free State cut many ties with London in 1937, becoming a republic in all but name.

Britain's Foreign Policy (1919-1939)

Britain did not suffer much physical damage during the First World War, but the cost in lives and money was very high. In the 1918 election, Lloyd George promised to make Germany pay for the war. However, at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, he took a more moderate approach. France and Italy insisted on harsh terms, including Germany admitting guilt for starting the war and paying for all Allied war costs. Britain reluctantly supported the Treaty of Versailles, though many experts thought it was too harsh on Germany.

Britain began to see a strong Germany as an important trading partner and worried about how the reparations would affect its own economy. The United States eventually helped Germany pay its debts to Britain and other Allies, and Britain used this money to repay its war loans to the U.S. The terrible memories of the war made Britain and its leaders strongly want peace during the interwar years.

The 1920s

Britain kept close ties with France and the United States. It did not want to be isolated. It sought world peace through naval arms limitation treaties and peace with Germany through the Locarno treaties of 1925. A main goal was to help Germany become peaceful and prosperous again.

Britain played a big role in the Washington Naval Conference of 1921, working towards limiting naval weapons for major powers. By 1933, disarmament efforts had failed, and the focus shifted to rearming for a possible war against Germany.

At the Washington Conference, Britain gave up its long-standing policy of having a navy as strong as the next two naval powers combined. Instead, it accepted having a navy equal to the United States. It also promised not to strengthen its forts in Hong Kong, which were close to Japan. The treaty with Japan was not renewed, but Japan was not yet expanding aggressively. London moved closer to Washington.

The 1930s

The biggest challenge came from dictators: Benito Mussolini in Italy from 1923, and then Adolf Hitler in a much stronger Nazi Germany from 1933. Britain and France chose not to interfere in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). The League of Nations failed to stop the threats from the dictators. British policy was to "appease" them, hoping they would be satisfied. For example, sanctions against Italy for invading Ethiopia failed and were dropped in 1936.

Germany was a difficult case. By 1930, many British leaders and thinkers believed that all major powers were to blame for the 1914 war, not just Germany. They thought the Treaty of Versailles was too harsh. This view led to support for appeasement policies until 1938, as Germany's rejections of the treaty seemed justified.

The Start of the Second World War

By late 1938, it was clear that war was coming, and Germany had the world's most powerful military. British military leaders warned that Britain needed more time to prepare its air force and air defenses. Appeasement—giving in to Germany's demands—was the government's policy until early 1939. The last act of appeasement was the Munich Agreement of 1938, where Britain and France allowed Hitler to take parts of Czechoslovakia.

However, Hitler then seized the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 and threatened Poland. In response, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain stopped appeasement and promised to defend Poland. Hitler then made a surprising deal with Joseph Stalin to divide Eastern Europe. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Britain and France declared war. The British Commonwealth followed Britain's lead.

Britain's Economy (1918-1939)

Taxes went up a lot during the war and never returned to their old levels. A rich person paid 8% of their income in taxes before the war, and about a third afterward. Much of this money went to unemployment benefits. About 5% of the national income each year was moved from the rich to the poor. Despite this, many people enjoyed a better life than ever before, with longer holidays, shorter working hours, and higher wages.

The British economy was not very strong in the 1920s. Heavy industries like coal and steel, especially in Scotland and Wales, saw sharp declines and high unemployment. Exports of coal and steel were cut in half by 1939. Businesses were slow to adopt new ways of working and managing, like those from the US. The shipping industry, which had been very strong for over a century, struggled. When world trade sharply declined after 1929, its situation became critical.

In 1925, the finance minister, Winston Churchill, put Britain back on the gold standard. Many economists believe this contributed to the economy's poor performance. Others point to other factors, like the effects of the war and changes in working hours.

By the late 1920s, the economy had stabilized, but Britain had fallen behind the United States as a leading industrial power. There was also a big economic difference between the north and south of England. The south and the Midlands were quite prosperous by the 1930s, while parts of South Wales and the industrial north became known as "distressed areas" due to very high unemployment and poverty. Despite this, living standards generally improved. Local councils built new houses with modern facilities like indoor toilets and electricity. The private sector also saw a boom in house building during the 1930s.

Workers and Unions

During the war, trade unions were encouraged, and their membership grew from 4.1 million in 1914 to 6.5 million in 1918. It peaked at 8.3 million in 1920 before falling to 5.4 million in 1923. Strikes became less common in the early 1920s.

The coal industry was struggling. The best coal seams were running out, making it more expensive to mine. Demand for coal also fell as oil became a popular fuel. The 1926 general strike was a nine-day nationwide walkout. Over a million railway workers, transport workers, printers, and steelworkers supported 1.2 million coal miners who had been locked out by mine owners. The miners had refused demands for longer hours and less pay. The government had given money to the coal industry in 1925, but it wasn't enough. The Trades Union Congress (TUC), which represents all unions, called for the general strike to support the miners.

The government had prepared by stockpiling supplies, and essential services continued with the help of students and volunteers. All three major political parties were against the strike. Labour Party leaders worried it would make their party seem too radical. The general strike itself was mostly peaceful, but the miners' lockout continued, and there was some violence in Scotland. It was the only general strike in British history. Most historians see it as a unique event with few long-term effects. However, some believe it encouraged more working-class voters to join the Labour Party. The Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act 1927 made general strikes illegal and stopped unions from automatically paying dues to the Labour Party. This law was mostly removed in 1946. The coal industry continued to decline, and the Labour government nationalized the mines in 1947.

Starting in 1909, the Liberal Party pushed for a minimum wage for farm workers. Despite strong opposition from landowners, this was achieved by 1924. It raised wages for farm laborers by about 15% by 1929 and over 20% in the 1930s. This helped many farm worker families out of poverty, but it also reduced the number of people employed in farming.

Food and Diet

After the war, many new food products became available. Branded foods were advertised for being convenient. With fewer servants, housewives could buy instant foods in jars or powders that mixed quickly. Breakfast cereals like Kellogg's Corn Flakes started to become popular. Shops offered more bottled and canned goods, and fresher meat, fish, and vegetables. While wartime shortages had limited choices, the 1920s saw many new imported foods, especially fruits, along with better packaging and hygiene. Middle-class homes often had ice boxes or electric refrigerators, allowing them to store more food.

Studies during the Depression showed that the average person ate better than before. Food prices were low, but the poorest third of the population still suffered from poor nutrition. Teachers noticed the negative effects on poor children. In 1934, the government started a program to provide school children with milk for a small fee. This greatly improved their nutrition. During the Second World War, milk was given out for free, and participation rose to 90%. The rationing system during the war also improved the nutrition of the poorest people.

The Great Depression in Britain

The Great Depression started in the United States in late 1929 and quickly spread worldwide. Britain felt the main impact in 1931. Unlike some other countries, Britain had not experienced a big economic boom in the 1920s, so the downturn was less severe and ended sooner.

A Global Crisis

By summer 1931, the world financial crisis began to overwhelm Britain. Investors worldwide started withdrawing their gold from London. Loans from the Bank of France and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York helped, but didn't stop the crisis. This financial crisis led to a major political crisis in Britain in August 1931.

With growing deficits, bankers demanded a balanced budget. The Labour government, led by Ramsay MacDonald, agreed to raise taxes and cut spending, including a controversial 20% cut to unemployment benefits. This cut was unacceptable to the Labour movement. MacDonald wanted to resign, but the King insisted he stay and form an all-party "National government." The Conservative and Liberal parties joined, along with a few Labour members. However, most Labour leaders called MacDonald a traitor.

Britain then abandoned the gold standard in September 1931. Instead of the disaster many predicted, this turned out to be a big advantage. The value of the British pound dropped by 25%. This made British exports much cheaper and more competitive, which helped the economy slowly recover. The worst of the depression was over.

Britain's world trade fell by half between 1929 and 1933. Output from heavy industry dropped by a third. Jobs and profits fell in almost all areas. At its lowest point in summer 1932, 3.5 million people were officially unemployed, and many more had only part-time jobs. The government tried to work within the Commonwealth, raising tariffs on products from the United States, France, and Germany, while giving preference to Commonwealth members.

Organized Protests

Northern England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales faced very severe economic problems, especially if their economies relied on coal, steel, or shipbuilding. Unemployment reached 70% in some mining areas in the early 1930s. The government was careful and conservative, rejecting ideas for large public works projects.

In 1936, when unemployment was lower, 200 unemployed men marched from Jarrow to London. This highly publicized event, known as the Jarrow Crusade, aimed to show the suffering of the industrial poor. Although often seen as a symbol of working-class struggle, it caused divisions within the Labour Party and didn't lead to immediate government action. Unemployment remained high until the Second World War created many new jobs. George Orwell's book The Road to Wigan Pier describes the hardships of this time.

Despite the economic crisis, many historians now believe that Britain was generally prosperous, apart from areas with long-term high unemployment. Prices fell sharply between the wars, and average incomes rose by about a third. The term "property-owning democracy" was coined in the 1920s, and three million houses were built in the 1930s. Land, labor, and materials were cheap. Middle-class families bought new items like radios, telephones, electric cookers, and vacuum cleaners. They drove cars and went to cinemas. The depression actually led to a boom in consumer goods.

Society and Culture in Interwar Britain

During the interwar period, most people in England were ethnically similar, except for Chinese communities in cities like Liverpool and London. While regional accents were still common, they were declining, and some full dialects disappeared outside of literature. The 1921 census showed there were more women than men, partly due to higher infant mortality among males and wartime losses. The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 allowed women to join professions, but most women still depended on their husbands, especially in working-class homes. In most jobs, women were paid less than men.

Religion in a Changing World

The Church of England was traditionally linked to the upper classes and rural landowners. However, William Temple (1881–1944), a theologian and social activist, promoted Christian socialism. He became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1942 and wanted the Church of England to be more open and inclusive. He worked to improve relationships with other Christian groups, Jews, and Catholics.

A Slow Decline in Religious Practice

While the overall population grew, and Catholic membership kept pace, Protestant church membership slowly declined. From 5.7 million members in 1920, it fell to 5.4 million in 1940 and 4.3 million in 1970. The Church of England saw a similar decline. Methodism, the largest non-Anglican Protestant church, peaked in 1910 and then steadily declined. Many non-Anglican churches had strong bases in industrial areas that were now struggling. As families moved to southern England or suburbs, they often lost touch with their childhood religions. To try and stop the decline, the three main Methodist groups merged in 1932, and two major Presbyterian groups in Scotland merged in 1929. However, the decline continued.

People showed less enthusiasm for church, Sunday school attendance dropped, and there were fewer new ministers. Many prominent non-Anglicans even joined the Anglican church. There was less interest in funding missionaries and less intellectual discussion. People also complained about a lack of money.

One reason for the decline was that Protestants became less interested in sending their children to religious schools. The Anglican share of elementary school students fell from 57% in 1918 to 39% in 1939. As non-Anglican churches declined, their schools closed. For example, the Methodist Church operated 738 schools in 1902, but only 28 remained in 1996.

Britain still saw itself as a Christian country. Few people were atheists, and there was no strong anti-clerical movement. A third or more people prayed daily. Most people used church services for births, marriages, and deaths. Most believed in God and heaven, though belief in hell decreased after the many deaths of the First World War. After 1918, Church of England services rarely discussed hell.

The Prayer Book Controversy

Since 1688, Parliament had governed the Church of England, but it wanted to give more control to the Church itself. In 1919, Parliament passed a law to create the Church Assembly, which could make rules for the Church, subject to Parliament's approval.

A crisis arose in 1927 when the Church proposed to revise the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which had been used daily for over 250 years. The goal was to include moderate Anglo-Catholicism more easily. The Church Assembly approved the changes. However, Evangelicals within the Church and Nonconformists outside were very upset. They believed England's religious identity was strongly Protestant and anti-Catholic. They saw the revisions as giving in to Roman Catholicism. They gathered support in Parliament, which rejected the revisions twice after intense debates. The Anglican leaders compromised in 1929, strictly forbidding extreme Anglo-Catholic practices.

Divorce and the King's Abdication

Moral standards in Britain changed a lot after the world wars, moving towards more personal freedom. The Church tried to maintain its stance, especially against the rising trend of divorce. In 1935, it restated that "Christian men or women" could not remarry while their spouse was still alive.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang, believed that the King, as head of the Church of England, could not marry a divorced woman. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin strongly agreed, saying that while standards were lower after the war, people expected a higher standard from their King. Baldwin was supported by his Conservative Party (except Winston Churchill), the Labour Party, and the prime ministers of the Commonwealth.

King Edward VIII was determined to marry an American divorcée, Wallis Simpson. He was therefore forced to give up his throne in 1936. This was announced by Baldwin in Parliament on December 10 and made law the next day. Although public opinion showed him some support, the elite were against him, and he was practically forced into exile. Archbishop Lang publicly criticized the upper-class social circles Edward spent time in, saying they had standards "alien to all the best instincts and traditions of the people."

Historians suggest that Edward was not well prepared to be King and had personal weaknesses. Baldwin's actions helped ensure the monarchy remained a unifying force for the nation. Edward's younger brother became George VI. Both George V and George VI showed the value of a "democratic king" during the difficult times of the world wars, a tradition carried on by Elizabeth II.

Newspapers and Media

After the war, major newspapers competed fiercely for readers. Political parties, which used to have their own papers, couldn't keep up, and their papers were sold or closed. To sell millions of copies, newspapers focused on popular stories with strong human interest and detailed sports reports. Serious news was a smaller market, dominated by The Times and The Daily Telegraph.

Newspaper ownership became concentrated. By 1937, four men—Lords Beaverbrook, Rothermere, Camrose, and Kemsley—owned nearly half of all national and local daily papers in Britain. Their combined circulation was over thirteen million.

Just over half of British homes bought a daily newspaper in 1939. The Times of London was the most influential newspaper, known for its serious political and cultural news. Its editor, Geoffrey Dawson, supported Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's policy of appeasement towards Hitler. News reports from Berlin that warned of war were rewritten in London to support appeasement. However, in March 1939, The Times changed its stance and called for urgent war preparations.

The Liberal Manchester Guardian was highly respected abroad. The Daily Telegraph was a businessman's newspaper with the most advertising space. The Daily Mail appealed mostly to middle-class readers and was the first paper to cater to women and children. The only newspaper specifically for working-class readers was the Labour Daily Herald. The Times Literary Supplement was the most important literary magazine.

More Leisure Time

As people gained more leisure time, literacy, and wealth after 1900, there was more interest in all kinds of leisure activities for all social classes. Most pubs had public bars and saloon bars. Saloon bars cost a bit more for beer but offered a more select crowd and better furniture. Public bars were simpler, often with just advertisements and a dart-board.

Taxes on beer increased, but there were more alternatives like cigarettes (popular with 8 out of 10 men and 4 out of 10 women), movies, dance halls, and Greyhound racing. Football pools offered the excitement of betting on game results. New housing estates with small, affordable homes made gardening a popular outdoor hobby. Church attendance dropped to half the level of 1901.

Annual holidays became common. Tourists flocked to seaside resorts; Blackpool hosted 7 million visitors a year in the 1930s. Organized leisure was mainly for men, with middle-class women participating less. Participation in sports and other leisure activities increased for the average English person, and interest in watching sports grew dramatically. By the 1920s, cinema and radio attracted huge audiences of all ages and genders, with young women leading the way. Working-class men were enthusiastic football spectators. They sang along at music halls, kept pigeons, gambled on horse racing, and took their families to seaside resorts in summer.

Cinema and Radio

The British film industry started in the 1890s, building on the strong reputation of London's theater for actors and directors. However, the American film market was much larger and richer. Hollywood became dominant in the 1920s, producing over 80% of the world's films and attracting top British talent. Efforts to compete, like setting a quota for British films, failed. Hollywood also controlled the profitable Canadian and Australian markets. Bollywood (in India) dominated the huge Indian market. The most famous directors remaining in London were Alexander Korda and Alfred Hitchcock. There was a creative revival in British film from 1933–1945, especially with Jewish filmmakers and actors fleeing the Nazis. Meanwhile, huge cinemas were built for the large audiences who wanted to see Hollywood films. In Liverpool, 40% of the population went to one of the 69 cinemas once a week, and 25% went twice. Some traditionalists complained about American cultural influence, but its long-term impact was minor.

In radio, British audiences had only one choice: the high-quality programs of the BBC, which had a monopoly on broadcasting. John Reith (1889–1971), a very moral engineer, was in charge. His goal was to broadcast "All that is best in every department of human knowledge, endeavor and achievement." He wanted to maintain a high moral tone. Reith successfully prevented an American-style radio system where the goal was to attract the largest audiences for advertising. The BBC had no paid advertising; its money came from a license fee paid by people who owned radios. Highbrow audiences enjoyed it greatly. While American, Australian, and Canadian stations broadcast popular sports like baseball and rugby, the BBC focused on national rather than regional audiences. They covered boat races, tennis, and horse racing well, but were reluctant to spend limited airtime on long football or cricket games, despite their popularity.

Sports and Games

The British showed a deep and varied interest in sports. They valued sportsmanship and fair play. Cricket became a symbol of the Imperial spirit throughout the Empire. Football became very popular among urban working classes, bringing rowdy spectators to the sports world. In some sports, like rugby and rowing, there were debates about keeping amateur purity.

New games quickly became popular, including golf, lawn tennis, cycling, and hockey. Women were more likely to play these new sports than the older, more established ones. The aristocracy and wealthy landowners, who controlled land rights, dominated hunting, shooting, fishing, and horse racing.

Cricket was well established among the English upper class by the 18th century and was a major part of sports competition in public schools. Army units across the Empire encouraged locals to learn cricket for entertainment. Most Dominions, except Canada, adopted cricket as a major sport. International cricket matches, called Test matches, began by the 1870s, with the most famous being between Australia and England for The Ashes.

For sports to become fully professional, coaching had to develop first. It gradually became professional in the Victorian era and was well established by 1914. During the First World War, military units sought out coaches to oversee physical training and develop morale-boosting teams.

Reading Habits

As literacy and leisure time increased after 1900, reading became a popular pastime. New adult fiction books doubled in the 1920s, reaching 2,800 new books a year by 1935. Libraries tripled their book collections and saw high demand for new fiction. A major innovation was the inexpensive paperback book, started by Allen Lane (1902–70) at Penguin Books in 1935. The first titles included novels by Ernest Hemingway and Agatha Christie. They were sold cheaply (usually sixpence) in many different stores, like Woolworth's. Penguin aimed for an educated middle-class audience. It avoided the less refined image of American paperbacks. The books suggested cultural self-improvement and political education. The more political Penguin Specials, often with a leftist view, were widely distributed during the Second World War. However, the war years caused shortages of staff for publishers and bookstores, and a severe shortage of paper. An air raid on Paternoster Row in 1940 burned 5 million books in warehouses.

Romantic fiction was especially popular, with Mills and Boon as the leading publisher. Adventure magazines became very popular, especially those published by DC Thomson. This publisher sent people around the country to talk to boys and learn what they wanted to read about. The stories in magazines, comic books, and cinema that most appealed to boys featured the heroic British soldiers fighting exciting and just wars. DC Thomson launched the first The Dandy Comic in December 1937. It had a new design that was different from the usual large, less colorful children's comics. Thomson followed its success with a similar comic, The Beano, in 1938.

Books about the First World War became very popular during a revival from 1928–1931. This started in Germany with books like Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front (1928), which were printed in parts in British newspapers. Other popular war books included Siegfried Sassoon's Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928) and Robert Graves's Good-Bye to All That (1929). The most successful play in 1929 was R. C. Sherriff's Journey's End. These war books brought back memories of the horrors of the First World War and increased anti-war feelings.

During this time, and stretching into the 1950s and 1960s, a group of writers known as The Inklings began to meet. J. R. R. Tolkien published The Hobbit in 1937, and C. S. Lewis published The Allegory of Love in 1937. Lewis would later publish Out of the Silent Planet in 1938, starting his famous Space Trilogy, and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in 1950, starting his The Chronicles of Narnia series. Tolkien would publish On Fairy-Stories in 1939 and The Fellowship of the Ring in 1954, starting his The Lord of the Rings series.

|

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |