Book of Common Prayer (1662) facts for kids

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer is a very important church book for the Church of England. It is also used by other Anglican churches around the world. This prayer book has been printed and used regularly for over 360 years. Many other versions of the Book of Common Prayer and other church texts are based on it.

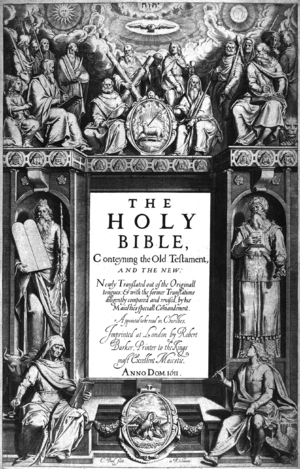

People admire the 1662 prayer book for its beautiful writing and its helpful prayers. It has even shaped the English language. Using it alongside the King James Version of the Bible helped more people learn to read between the 1500s and 1900s.

This prayer book has deeply influenced Christian worship and traditions. Its ideas have inspired many Christian groups, both inside and outside the Anglican Communion. These include Anglo-Catholicism, Methodism, and Unitarianism. Today, the Church of England mostly uses Common Worship for public services. This is because the 1662 book uses older language and doesn't have prayers for modern life. Still, the 1662 prayer book remains a key text for the Church of England and many Anglican churches.

Contents

- Why was the 1662 Prayer Book created?

- How the 1662 Prayer Book was Made

- How the Church of England Used It

- Global Use and Translations

- Later Changes and Replacements

- What's Inside the 1662 Prayer Book?

- Influence and Importance

- Other Anglican Versions

- Used by Other Groups

- Related Texts

- Images for kids

Why was the 1662 Prayer Book created?

After the English Reformation, the Church of England separated from the Catholic Church. Church services then began to be written in English. The first Book of Common Prayer from 1549 replaced the old Catholic service books. This book was mostly a translation of older Latin services. It included the Communion service and daily prayers like Matins (Morning Prayer) and Evensong (Evening Prayer). It also had forms for ordaining bishops, priests, and deacons.

Under King Edward VI, the 1552 Book of Common Prayer became much more Protestant. This trend continued with the 1559 edition after Queen Elizabeth I became queen. For a while, the 1559 edition was the second most common book in England, after the Bible. An Act of Parliament made sure every church had a copy.

The 1559 prayer book, along with the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion (1563) and the Book of Homilies (1571), helped define Anglicanism. It made the Church of England different from both Catholicism and other Protestant churches. This period is known as the Elizabethan Religious Settlement.

Puritan Opposition to the Prayer Book

Some Protestants, called Puritans, did not like parts of the Book of Common Prayer. They especially disliked elements that were kept from before the Reformation. Church leaders like Matthew Parker, the Archbishop of Canterbury, tried to make people use certain church clothes, like the surplice and cope. This made the Puritans even more upset.

The Puritans showed their dislike for the prayer book at the Hampton Court Conference in 1604. The Jacobean prayer book that came from this meeting was only slightly changed. However, the conference also approved the creation of the Authorized Version of the Bible, also known as the King James Version.

The Puritans and Parliament continued to oppose the prayer book. Using the prayer book became a sign of supporting the King. In 1637, a new prayer book, influenced by William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was forced upon the Church of Scotland. This caused a riot that led to the First Bishops' War. In 1640, the Puritans asked Parliament to get rid of bishops and called the prayer book "Romish".

When the King's supporters lost the English Civil War and King Charles I was executed, England became a Commonwealth under Puritan rule. The prayer book was banned in 1645, and the Directory for Public Worship was introduced instead. Some priests still used the prayer book secretly, even memorizing parts of it. Other supporters of the prayer book, like Laud, were imprisoned. Laud was executed in 1645.

How the 1662 Prayer Book was Made

The Restoration and Savoy Conference

After the Puritan rule ended, King Charles II returned to the throne in 1660. This was called the Stuart Restoration. Church leaders wanted to bring back the prayer book. However, the surviving Puritans, called Nonconformists, wanted to prevent the prayer book and other old Anglican practices from returning.

Both sides agreed that the prayer book needed some changes. This led to the Savoy Conference in 1661 in London. Twelve Anglican bishops and Puritan ministers, along with assistants, attended. The Anglicans suggested small changes to the 1559 prayer book. They presented it as a middle way between Catholic and Protestant practices. The conference ended with few changes that pleased the Puritans. It led to the creation of a new prayer book.

John Cosin, a bishop who had studied the prayer book during his exile, made many suggestions for changes. These notes were put into a manuscript known as the Durham Book. Many of his ideas were accepted and put into the final version.

Parliament then passed a series of laws called the Clarendon Code. These laws aimed to stop Puritans from holding public office and to make sure everyone worshipped using official Anglican texts. The Act of Uniformity 1662, passed on May 19, 1662, made the 1662 prayer book official. It replaced the 1559 book on August 24, 1662.

On that day, between 1,200 and 2,000 Puritan ministers were forced out of their churches. This event is known as the Great Ejection or Black Bartholomew. In 1664, the Conventicle Act punished anyone over 16 who attended a worship service not using the 1662 prayer book. These Nonconformists then helped grow other Protestant groups, making it harder for the Church of England to have everyone worship in the same way.

Early Printings of the 1662 Prayer Book

Between the 1549 and 1662 editions, there were over 500 printings of the Book of Common Prayer by the 1730s. Each printing usually had 2,500 to 3,000 copies. As printing technology got better, the number of copies increased. Between 1836 and 1846, up to half a million copies of the 1662 prayer book were printed each year. Oxford University Press started printing a large number of these books.

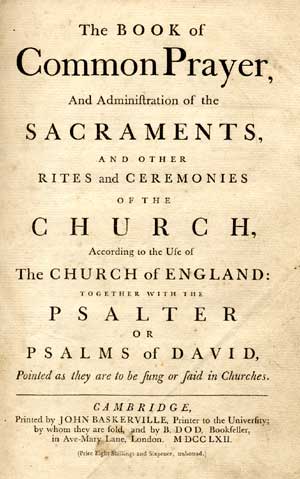

Some early printings still used the old-fashioned blackletter script. However, roman fonts became standard for the instructions (rubrics) in the 1662 prayer book. In the 1700s, John Baskerville printed the 1662 prayer book using his special font. His printings were known for their beautiful decorations.

How the Church of England Used It

For about 300 years, the 1662 prayer book stayed mostly the same. However, small additions were made early on. These included special prayers for events like the Gunpowder Plot and the execution of King Charles I. There was also a prayer of thanks after the Great Fire of London in 1666.

The 1662 prayer book did not have services for every special event. So, the Church of England had to create separate forms for things like consecrating churches. When James II of England became king, the old coronation service had to be brought back.

King James II was openly Catholic. He favored practices that excluded Nonconformists even more. But in 1688, the Glorious Revolution brought William III and Mary II to the throne. They were Calvinists and improved relations with the Nonconformists.

William III supported a group to make changes to the Church of England's services. They wanted to make the prayer book more open to Nonconformists. A revised prayer book was created in 1689, but it was never officially approved. The 1688 Toleration Act was passed instead, which allowed Nonconformists more freedom.

Many attempts were made to revise the prayer book throughout the 1800s. Dozens of ideas were published, but none became official. The only changes made were removing the Gunpowder Plot prayers and adding a general prayer for the reigning monarch's accession day. A committee in 1877 spent 15 years trying to improve the prayer book's punctuation, but nothing came of it.

Global Use and Translations

As the British Empire grew, the 1662 prayer book helped comfort those who moved abroad. For people on long ship voyages, the prayer book had special "Forms of Prayer to be used at Sea." The 1662 prayer book was also designed for use in new territories. It included a form for baptizing adults, partly to help with the "baptism of natives in our plantations."

The 1549 prayer book had been translated into Latin for academic reasons. This continued with the 1662 prayer book, which also saw a Greek translation. More practical translations were made into local languages. The Thirty-Nine Articles supported the idea of translating church texts.

The first Spanish-language edition of the 1662 prayer book was published in 1707. It was translated by Don Felix Anthony de Alvarado. Later, a 1715 edition was put on the Catholic list of prohibited texts because it encouraged Spaniards to worship in their own language.

In North America, the 1662 prayer book was translated into several Native American languages. The first was Mohawk in 1715. It was also translated into Algonquian languages in British colonial Canada and the Thirteen Colonies. Missionaries like Edmund Peck translated it into Inuktitut in 1881.

Many different translations of Anglican services were made into Chinese languages in the 1800s. These were used to create a prayer book for the Holy Catholic Church of China. Later, in 1957, the Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui introduced a prayer book based on the 1662 and 1928 proposed prayer books.

Later Changes and Replacements

The Proposed 1928 Revision

After First World War, there was a strong desire to update the 1662 prayer book. This was partly due to the Oxford Movement, which started in 1833 and focused on older church traditions. Anglo-Catholics, in particular, wanted changes.

A group of bishops and scholars met in 1906 to discuss what church items and clothes were allowed by the 1662 prayer book. Their findings caused debate. In 1911, a committee was formed to discuss revisions.

This group, which included both Anglo-Catholic and Evangelical members, first met in 1912. During the war, some Anglo-Catholic practices, like keeping the Eucharist (Holy Communion bread and wine) for later use, were allowed. Many clergy felt a greater need for revision after the war.

By 1927, a new proposed prayer book was created. Supporters said it would only be an alternative to the 1662 edition, not replace it entirely. This new text was sent to the House of Commons for approval. However, it was defeated in December 1927. Some thought it was too close to Catholic practices, while others, like Winston Churchill, supported it. A second attempt with small changes also failed in 1928. Even though it wasn't approved, this 1928 proposed prayer book was still printed and used by some.

Alternative Service Book and Common Worship

After the 1928 text failed, new ideas about church services appeared. This was largely due to the Liturgical Movement, which sought to renew church worship. After Second World War, Anglicans wanted liturgical reforms, including prayer book revisions.

Instead of replacing the 1662 prayer book directly, the Church of England gradually added alternative services. The first, Alternative Services Series 1, was published in 1966. Series 2 kept traditional language but had new orders for rites. Series 3 was the first to use modern language.

In 1974, the church was allowed to print these alternatives in full books. This measure also permanently allowed the church to create alternative services, as long as the 1662 prayer book was protected. In 1980, the Alternative Service Book was published.

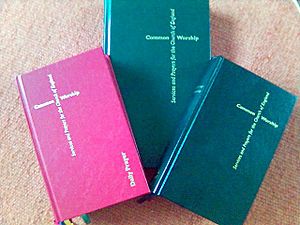

In 2000, a new collection of approved Church of England services was published as Common Worship. This book offers many choices for different services. The 1662 Communion service is even included as an option within Common Worship. Because Common Worship is now favored, fewer churches use the 1662 prayer book. Groups like the Prayer Book Society work to encourage its continued use.

What's Inside the 1662 Prayer Book?

The 1662 prayer book had about 600 changes and additions from the previous edition. It included a new preface written by Robert Sanderson. This preface explained the changes, such as clearer instructions for the priest, updated old words, new Bible translations, and new services. This preface is still in the 1962 prayer book used by the Anglican Church of Canada. The 1662 book also kept the 1549 prayer book's preface, called "Concerning the Service of the Church."

The Thirty-Nine Articles were not in the original 1662 prayer book but were formally added in 1714. King Charles I's 1628 statement defending the Articles is also included.

The entire book of Psalms is in the prayer book. The version of the Psalms used is from the Great Bible, translated by Myles Coverdale. This translation had been used since the 1549 prayer book. However, for the New Testament readings, the 1662 prayer book used the Authorized Version of the Bible (King James Version).

Holy Communion Service

The priest says one of two prayers for the monarch before the main prayer of the day. These prayers often followed older models, many being translations from ancient services. Three new prayers were added in the 1662 prayer book.

The main prayer of the Communion service, called the Eucharistic prayer, follows a pattern set in 1552. It includes:

- Sursum corda (Lift up your hearts)

- A special Preface

- Sanctus (Holy, Holy, Holy)

- Prayer of Humble Access

- Prayer of Consecration (blessing the bread and wine)

- Thanksgiving after Communion

The Black Rubric was added back into the 1662 prayer book. This instruction explained that kneeling during Communion was a sign of thanks to Christ, not a belief that the bread and wine physically changed. It allowed for a limited belief in Christ's real presence in the Eucharist.

By 1714, Holy Communion was usually celebrated on Sundays around 9:45 AM. Even though it wasn't the main Sunday service until World War I, it was still highly respected.

Daily Prayer Services

The 1662 prayer book kept many parts of the 1552 Daily Office (Morning and Evening Prayer). It added special prayers for the state and the royal family. These prayers are found in the suffrages, collects, and Litany. The Litany was mostly written by Thomas Cranmer in 1544. Other occasional prayers and thanksgivings were added, including prayers for Ember Weeks.

The 1662 prayer book also added a rule allowing an anthem (a special song) to be sung at the end of the Daily Office. These anthems led to new interest in Anglican church music. They became a regular part of services in cathedrals and collegiate churches, where choirs were common.

By 1714, Sunday Morning Prayer usually started at 10 AM. Morning Prayer was the main Sunday service until the early 1900s. However, by then, some criticized the 1662 prayer book's Daily Office for not fully reflecting the Reformation's ideas for public daily prayer.

Other Special Services

The 1662 prayer book included services for baptism. The form for baptizing "such as are of Riper Years" was useful for people converting to Christianity in the colonies. It was also for those from churches that did not practice infant baptism. The rules for public baptism were changed, and a blessing of the baptismal font was added.

A purification ritual for women after childbirth, called the Churching of Women, was included. The 1662 prayer book made some changes to this service from the 1559 version.

The 1662 prayer book's marriage service changed the rules from older practices. It allowed the marriage service to be held separately from a Communion service. The 1662 marriage service is still a legal option for weddings in the Church of England. Like earlier English prayer books, the wedding ring is placed on the left hand.

Ordination Services

The 1662 ordinal (the service for ordaining clergy) was mostly the same as the first Edwardine Ordinal. However, before 1662, it was a separate book. In 1662, it was added to the main prayer book. Some important additions were made to the services for ordaining priests and consecrating bishops. These additions highlighted the roles of priests and bishops, in contrast to the views of Puritans. A new version of the Veni Creator Spiritus (Come, Holy Spirit) was introduced.

Changes were made to the ordinal's preface in 1661 to distinguish Anglican ministry from other forms of ministry that appeared during the Commonwealth. The 1662 prayer book's service for ordaining priests emphasized the importance of preaching. Also, the minimum age for deacons was raised from 21 to 23.

Influence and Importance

The 1662 prayer book has greatly influenced the modern English language. It is second only to the Bible in the number of common sayings it has contributed, according to the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. The book has also become a symbol of English national identity.

Rowan Williams, a former Archbishop of Canterbury, said in 2005 that the 1662 prayer book had a big impact on English language and literature. He also described it as creating a "doctrinal and devotional climate" rather than expressing fixed beliefs. This flexibility was even mentioned in the 1662 preface.

After becoming Catholic, English writer G. K. Chesterton called the 1662 prayer book "the masterpiece of Protestantism." He felt it was best when it stayed close to Catholic traditions, calling it "the last Catholic book."

The Global Anglican Future Conference, a group of conservative Anglicans, stated in 2008 that the 1662 prayer book is "a true and authoritative standard of worship and prayer." They said it should be translated and adapted for different cultures.

Other Anglican Versions

After 1690, the Scottish Episcopalians used printings of the 1662 prayer book. By the early 1700s, some Scottish Episcopalians wanted a new service book. They felt the 1662 prayer book differed from four "primitive" practices. These included calling on the Holy Spirit during consecration and prayers for the dead.

The 1718 Nonjuror Office introduced an epiclesis, or a prayer asking the Holy Spirit to bless the bread and wine. This became a key feature of Scottish services. The 1662 prayer book became popular again in the 1800s in Scotland. However, it was officially replaced in 1912 when the Scottish Episcopal Church approved its own prayer book. Still, the 1662 Communion office was kept as an option in the 1912 and 1929 Scottish prayer books.

After the American Revolutionary War, the American Episcopal Church became independent. Its first prayer book, approved in 1789, was largely based on the 1662 prayer book. It removed some state prayers and added Scottish elements to the Communion service.

The Church of Ireland adopted the English 1662 prayer book in 1666. It had minor changes, like a service for visiting prisoners. The English version of the 1662 prayer book was used until 1871. It was replaced by a native Irish prayer book in 1878.

Throughout the 1800s, Anglican churches in other parts of the world developed their own prayer books, often based on the 1662 edition. For example, the Spanish Reformed Episcopal Church created its own prayer book in 1881. The Anglican Church in Japan also developed its prayer book between 1878 and 1895, drawing from the 1662 and American 1789 prayer books.

Even though newer Anglican services changed the pattern for the Eucharistic prayer, the 1662 version was often kept as an option. For example, the Anglican Church in Australia's 1995 A Prayer Book for Australia includes a modernized version of the 1662 rite. The Church in Wales adopted a revised prayer book in 1984. Its 2004 prayer book has seven Eucharistic prayers, some based on the 1662 model.

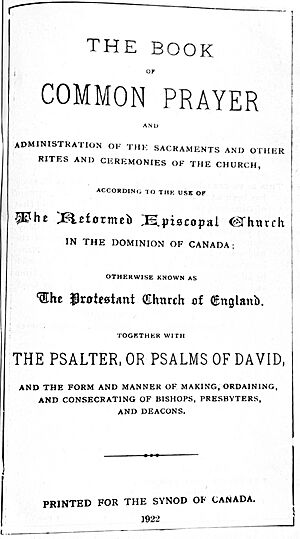

Non-Anglican Church Revisions

Both the Reformed Episcopal Church in the U.S. and Canada, and the Free Church of England in the UK, use prayer books partly based on the 1662 prayer book. The Reformed Episcopal Church's current 2003 prayer book mentions its connection to the 1662 book. Early versions were based more on the 1552 English prayer book. One bishop, Charles E. Cheney, felt that the 1662 prayer book had too many changes that made it less Protestant. The Free Church of England's 1956 prayer book also removed or explained parts of the 1662 prayer book that seemed too "Sacerdotal and Romanising."

The Anglican Church in North America (ACNA), founded in 2009, considers the 1662 prayer book its "standard for Anglican doctrine and discipline." When ACNA released its ordination and marriage services, the 1662 prayer book was a key basis. ACNA's 2019 Book of Common Prayer includes a Communion service that draws from the 1662 prayer book. A "Traditional Language Edition" of the 2019 prayer book, using Elizabethan English and the 1662 prayer book's language, was dedicated in 2022.

In 2021, a non-church group published The 1662 Book of Common Prayer: International Edition. It updated the language and spelling. It also included state prayers from other Anglican prayer books.

Used by Other Groups

Catholic Church

In 1980, Pope John Paul II allowed former U.S. Episcopal Church clergy to join the Catholic Church. They could celebrate services based on Anglican traditions. This led to the creation of "Anglican Use" liturgies for the Catholic Church. The Book of Divine Worship, published in 2003, contained services based on the 1979 U.S. prayer book.

In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI created special groups called personal ordinariates for former Anglicans in the Catholic Church. This expanded the use of Anglican Use liturgies. The Customary of Our Lady of Walsingham, a daily prayer book for former Anglicans in the UK, was published on the 350th anniversary of the 1662 prayer book. The 1662 prayer book forms the basis for Morning and Evening Prayer in the 2021 Divine Worship: Daily Office: Commonwealth Edition.

Eastern Orthodox Church

In 1869, Julian Joseph Overbeck reviewed the prayer book's services from an Eastern Orthodox viewpoint. The Russian Orthodox Church and later the Greek Orthodox Church approved his findings. The Russian Orthodox bishop in the U.S., Tikhon, asked if the U.S. Episcopal Church's 1892 prayer book could be adapted for Episcopal priests joining the Russian Orthodox Church. In 1904, the Russian Orthodox synod found some issues but allowed for a revised version.

The Liturgy of Saint Tikhon is a Western Rite Orthodox version of the Book of Common Prayer Communion service. It was first approved in 1977 and is named after Tikhon. This service is mostly from the U.S. prayer book tradition but has influences from the 1662 prayer book.

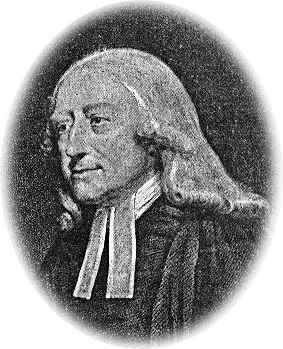

Methodism

John Wesley, a Church of England priest, started the Methodist movement in the 1700s. Wesley liked Anglican services. In 1784, he said he felt "there is no liturgy in the world... which breathes more a solid, scriptural, rational piety" than the 1662 prayer book. Early Methodist services were held outside regular church hours. They included preaching, Bible reading, and prayer, often using parts of Anglican services.

Wesley wanted to change the prayer book's services to help with evangelism. He also wanted them to better reflect his understanding of early Christian practices. He made shorter versions, such as The Sunday Service of the Methodists in North America in 1784. This was a shortened version of the 1662 prayer book for Methodists in the newly independent United States.

Wesley had some disagreements with the prayer book. He disliked the Athanasian Creed and the use of sponsors at baptism. In the 1784 Sunday Service, he removed services like private baptism and the visitation of the sick. Readings from the Apocrypha were removed, except for one from Tobit. References to The Books of Homilies, the Black Rubric, and saints' feast days were also deleted. However, modified Articles of Religion, based on the 39 Articles in the 1662 prayer book, were kept.

Even though some later Methodists found the 1662 prayer book too "Popish," Methodist services continued to be shaped by it. The British Wesley Methodist Church developed its own service book in 1882, based directly on the Book of Common Prayer. The 1784 Sunday Service was revised and reprinted many times. It remains a key text for Methodist churches in the U.S., influencing the United Methodist Church and the African Methodist Episcopal Church's Communion service.

Unitarianism

King's Chapel in Boston, Massachusetts, started as a Church of England parish in 1686. During the American Revolution, many of its members were loyal to Britain and left. The Anglicans who stayed allowed Congregationalists to share their church. In 1782, James Freeman became a lay reader and introduced his own Unitarianism beliefs.

Using another modified prayer book as a guide, Freeman and the King's Chapel congregation created a version of the 1662 prayer book in 1785. It was changed to fit their nontrinitarian beliefs (not believing in the Trinity). The King's Chapel was not allowed to join the new U.S. Episcopal Church. So, it became the first Unitarian church in the U.S. King's Chapel still operates as an independent Unitarian church, using its modified 1662 prayer book.

Related Texts

Hymnals

The Church of England does not have one official hymnal (book of hymns). However, several hymnals were created to be used with the 1662 prayer book. Hymns became more popular in churches by the 1830s, partly due to the influence of Methodist practices. Hymns Ancient and Modern was published in 1861. A 1904 revision was not well-received because it changed words and removed popular hymns.

Percy Dearmer, a vicar in London, felt that Hymns Ancient and Modern was not good enough. He worked with Ralph Vaughan Williams to create his own hymnal, The English Hymnal, published in 1906. This hymnal provided hymns for the 1662 prayer book services. It had a leaning towards Anglo-Catholic views. Because it included hymns for the Virgin Mary and the dead, one diocese banned it. An abridged version was printed in 1907. The English Hymnal was regularly used until the 1980s. The 1986 revision, the New English Hymnal, has largely replaced the older versions.

Supplements for Ritual and Rules

In 1894, Ritual Notes was published to give more details to Church of England priests about church rituals. It was meant to be used with the 1662 prayer book. It was also popular with Anglo-Catholics in the U.S. Episcopal Church. Its last edition was published before the 1979 American prayer book was approved. This newer prayer book was too different for Ritual Notes to be useful, so its popularity declined. Another similar book, The Parson's Handbook, was created by Percy Dearmer in 1899.

Images for kids

-

Cover page to the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, as printed by John Baskerville for Cambridge in 1762

-

Jenny Geddes rejects Laud's prayer book in St. Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh, 23 July 1637

-

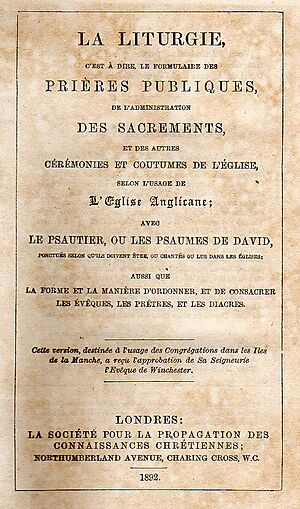

An 1892 Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge printing of the 1662 prayer book in French. The John Durel French translation was used by Guernésiais speakers into the 20th century.

-

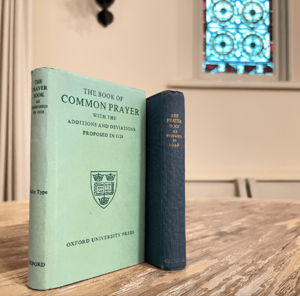

Two printings of the proposed 1928 prayer book

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |