History of Canada (1763–1867) facts for kids

| 1763–1867 | |

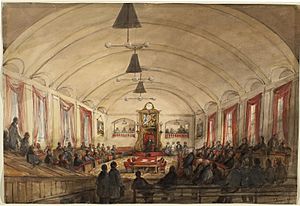

Inside the Parliament of the Province of Canada in Montreal, 1848

|

|

| Preceded by | French colonial era |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Post-Confederation era |

After the Treaty of Paris in 1763, New France (which included the colony of Canada) officially became part of the British Empire. The British changed the colony's name to the Province of Quebec. Later, with the Constitutional Act 1791, it became known as the Canadas.

In 1840, the Act of Union 1840 joined Upper and Lower Canada into the United Province of Canada. By the 1860s, people wanted to form a new country by joining the Canadas with other British colonies in North America. This led to Confederation in 1867. Some other British colonies, like Newfoundland and British Columbia, and large areas like Rupert's Land, joined Canada later.

Contents

- New France Becomes British

- The American Revolution's Impact

- After the American War

- War of 1812: Defending the Canadas

- The Fur and Timber Trades

- "Responsible Government" and Rebellions

- Lord Durham's Report

- The Act of Union (1840)

- British Colonies on the Northwest Coast

- Trade with the United States

- Confederation: Forming a New Country

- See also

New France Becomes British

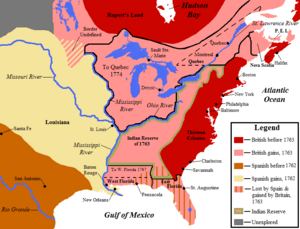

The Seven Years' War ended with Great Britain taking over all of France's colony of Canada in North America. The war officially ended on February 10, 1763, with the Treaty of Paris. France gave up all its lands in North America to Britain, except for Louisiana (which went to Spain) and two small islands near Newfoundland (Saint-Pierre and Miquelon).

Life in the St. Lawrence Valley

When Britain took over Canada, it gained control of a long strip of land along the St. Lawrence River. About 70,000 French-speaking Roman Catholics lived there. This area was expanded and renamed the Province of Quebec under the Quebec Act of 1774.

Many British people hoped the French Canadians would become more like them. However, the Quebec Act allowed French Canadians to keep their Catholic religion and their French system of civil law. This act made the thirteen British colonies to the south (which would become the United States) very angry.

Changes on the Atlantic Coast

The island colony of Newfoundland had been mostly British for a long time before France gave up its claims there. An English-speaking society was already in place by 1763, though two islands were set aside for French fishermen.

In the rest of the Maritimes, the British had forced many French colonists from Acadia to leave in 1755. These people became the Cajun population in Louisiana. But this did not happen again in 1763. The remaining Mi'kmaq and Wabanaki Confederacy Indigenous peoples promised loyalty to the British Crown.

The British had already taken over Acadia (which included the Nova Scotia peninsula) in 1710. They had also built settlements like Halifax. The building of Halifax led to Father Le Loutre's War. This war, in turn, led to the British expelling the Acadians during the French and Indian War. When the British captured Cape Breton Island and Prince Edward Island, they also expelled Acadians from there. The few Acadians who returned later created today's Acadian society. After the Acadians were expelled, new settlements were formed by people from New England.

The American Revolution's Impact

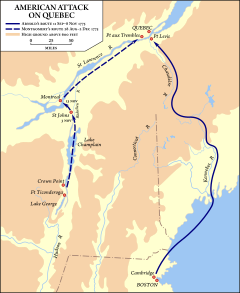

In 1775, American revolutionaries, called Patriots, tried to invade northeastern Quebec. Some people in Quebec supported the Patriots, especially English-speaking merchants. But the clergy (church leaders) and landowners were against it. The habitants (French-Canadian farmers) were split.

The Patriots captured Fort Saint-Jean and Montreal in November 1775. They then marched on Quebec City but failed to take it on December 31, 1775. After a long siege, British troops arrived in May 1776, forcing the Patriots to retreat. The Patriots were driven out of the province in June. About 250 Québécois joined the rebel army as they left.

Quebeckers living in the Great Lakes region also sided with the Patriots. They helped the Patriots take forts there. Many Quebec militiamen joined the Patriots and helped defeat the British at Yorktown in 1781.

In Nova Scotia, some people were against British rule. These were mainly Jonathan Eddy and John Allan, who had moved from Massachusetts. They led a small rebellion at Fort Cumberland in November 1776. British reinforcements arrived and scattered their forces.

The Maritime provinces also faced attacks from privateers (private ships allowed to attack enemy ships). Towns like Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island and Lunenburg, Nova Scotia were raided.

In southwestern Quebec, American forces had more success. In 1778, George Rogers Clark and his men captured Kaskaskia. They later retook Vincennes from the British in February 1779. About half of Clark's fighters were Canadian volunteers who supported the Americans.

In the end, Britain lost the Revolutionary War. They gave up parts of southwestern Canada to the new United States in the Treaty of Paris. About 50,000 United Empire Loyalists, who wanted to stay loyal to Britain, moved to the British North American colonies. These colonies included Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Prince Edward Island.

To give Loyalists more political freedom, Britain created the colony of New Brunswick in 1784. Quebec was also divided into Lower Canada and Upper Canada in 1791. This allowed the 8,000 Loyalists in Upper Canada to have a province with British laws. Many Loyalists were of African descent, including former slaves who gained freedom by helping the British. In 1793, Upper Canada became the first British area to pass a law to end slavery gradually.

After the American War

After the war, the British expanded their trade in the North Pacific. Spain and Britain had a disagreement over the area in 1789, called the Nootka Crisis. Spain had to back down, which opened the way for British expansion.

British explorers like George Vancouver explored the Pacific Northwest coast. On land, explorers like Sir Alexander Mackenzie searched for a river route to the Pacific for the North American fur trade. In 1793, Mackenzie became the first European to cross North America overland north of the Rio Grande. His journey happened twelve years before the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Soon after, John Finlay, Mackenzie's companion, founded Fort St. John, the first permanent European settlement in British Columbia. Other explorers like David Thompson and Simon Fraser also pushed into the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Coast, expanding British North America westward.

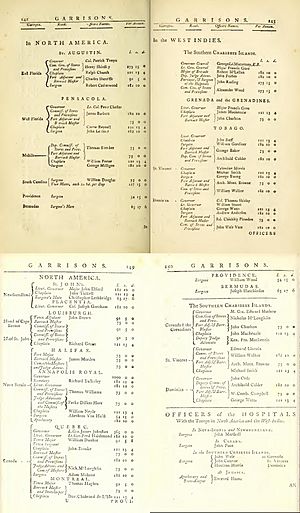

From 1783 to 1854, the British Empire's colonies, including British North America, were managed by the Home Office and later the War Office. In 1824, the Empire was divided into four main areas: North America, West Indies, Mediterranean and Africa, and Eastern Colonies.

North America included:

In 1854, the Colonial Office and War Office were separated. This divided the civil and military control of the Empire. The military administration of British colonies was then split into nine districts. The "North America and North Atlantic" district included:

North America and North Atlantic

- New Westminster (British Columbia)

- Newfoundland

- Quebec

- Halifax

- Kingston, Canada West

- Bermuda

The island of Bermuda was grouped with the Maritime provinces until Canada became a country in 1867. After that, it was usually grouped with the British West Indies.

The Royal Navy established a base in Bermuda in 1794. This base became the year-round headquarters for the "North America and West Indies Station" in 1821. Bermuda and Halifax, Nova Scotia, became important military strongholds for Britain.

A British Army garrison was also set up in Bermuda in 1794. It grew larger in the 1800s to defend the naval base and to launch attacks against the United States if needed. During the War of 1812, forces from Bermuda carried out attacks, like the Burning of Washington, to draw American forces away from the Canadian border.

War of 1812: Defending the Canadas

In the War of 1812, the Canadas became a battleground between Britain and the young United States. Americans tried to invade Upper Canada but failed. They thought many Canadian colonists would support them, but this was not true. Most settlers in Upper Canada were Loyalists or French colonists who did not want to join the United States.

The first American invasion in October 1812 was defeated by General Isaac Brock at the Battle of Queenston Heights. Americans invaded again in 1813, capturing Fort York (now Toronto). Later, they took control of the Great Lakes. However, they had less success in Lower Canada, where they were defeated at the Battle of Châteauguay and the Battle of Crysler's Farm.

The Americans were driven out of Upper Canada in 1814 after the Battle of Lundy's Lane. The War of 1812 is seen as a victory against American invasions in English Canada. Many heroes like Isaac Brock and Laura Secord emerged from this war.

The Fur and Timber Trades

For centuries, the fur trade was very important in North America. The French started it, but the British took over as they gained more land. Indigenous peoples were central to the trade because they were the main fur trappers. This gave them a political voice.

By the 1830s, changing fashions in Europe caused fur prices to drop sharply. This led to the collapse of the fur market. Many Indigenous nations suffered greatly from this economic loss.

As the fur trade declined, the timber trade became Canada's most important product. The industry grew in three main areas. First, the Saint John River system was used. Trees were cut in New Brunswick and sent to Saint John, then shipped to England.

When this area could not meet demand, the trade moved to the St. Lawrence River. Logs were shipped to Quebec City and then to Europe. Later, the trade expanded westward to the Ottawa River system. By 1845, this area provided three-quarters of the timber shipped from Quebec City. The timber trade became a huge business. In one summer, 1200 ships were loaded with timber at Quebec City alone.

"Responsible Government" and Rebellions

After the War of 1812, movements for political reform grew in both Upper and Lower Canada. These movements were influenced by American and French ideas about republics. The colonial legislatures (law-making bodies) were controlled by wealthy groups, like the Family Compact in Upper Canada and the Château Clique in Lower Canada.

Moderate reformers, such as Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine, wanted a more representative government. They called this "responsible government". This meant the government would be accountable to the people of the colonies, not just to officials in London. It was a big change from the old system where the governor made most decisions.

More radical reformers, like William Lyon Mackenzie and Louis-Joseph Papineau, wanted full equality or a complete break from British rule to form a republic.

Louis-Joseph Papineau was elected speaker of the colonial assembly in 1815. His reform ideas were ignored by the British. In 1834, the assembly passed The Ninety-Two Resolutions, listing their complaints. Papineau organized protests, and the government ordered his arrest. The Patriotes (his supporters) started the Lower Canada Rebellion in the fall of 1837. British troops quickly stopped the rebellion, and Papineau fled to the United States. A second rebellion broke out a year later but was also put down.

William Lyon Mackenzie, a Scottish immigrant and mayor of York (Toronto), organized the Upper Canada Rebellion in December 1837. People in Upper Canada were also unhappy with the undemocratic government. On December 4, rebels gathered near Montgomery's Tavern. British troops defeated them quickly on December 7. Mackenzie escaped to the United States.

Also in December, a group of Irish immigrants tried to take control of southwestern Ontario in the Patriot War. Government troops defeated them at Windsor.

Lord Durham's Report

Lord Durham was appointed Governor General of Canada in 1838. He was sent to find out why the Rebellions happened. He concluded that the main problem was the bad feelings between the British and French people in Canada.

His Report on the Affairs of British North America famously described "two nations warring in the bosom of a single state." Durham believed French Canadians were culturally behind. He thought that joining French and English Canada would help the colony progress. He hoped this political union would make French-speakers become more like English-speakers, solving the problem of French Canadian nationalism.

The Act of Union (1840)

Lord Sydenham took over from Lord Durham. He was responsible for putting Durham's ideas into action. The Act of Union 1840 was passed on July 23, 1840, and started on February 10, 1841. Upper and Lower Canada became Canada West and Canada East. Each had 42 seats in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada, even though Lower Canada had more people. English became the official language, and French was banned in Parliament and the courts.

Moderate reformers like Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine and Robert Baldwin worked hard to get "responsible government." They fought against two governors general, Sir Charles Bagot and Sir Charles Metcalfe. Metcalfe wanted to keep the governor's power. But he had to make some changes to gain support. He allowed the rebels of 1837–38 to return home and stopped the forced anglicization of French-speaking people.

Lafontaine and Baldwin brought French back as an official language in the Assembly and courts. Under Governor General Lord Elgin, a law was passed allowing former Patriote leaders to return. Papineau came back and briefly re-entered politics. Elgin also put responsible government into practice in 1848.

In 1849, a mob set fire to the parliament building in Montreal. This happened after a bill was passed to pay people who lost property during the Lower Canada rebellions.

One important achievement of the Union was the Canadian–American Reciprocity Treaty of 1855. This agreement allowed free trade in resources with the United States. This also helped ease tensions with the U.S., as earlier boundary disputes had been settled.

The Union Act of 1840 was not fully successful. It led to calls for a larger political union in the 1850s and 1860s. Events like the Battle of Ridgeway in 1866, where Irish nationalists invaded Ontario, also strengthened the idea of independence.

British Colonies on the Northwest Coast

Spain first explored the northwest Pacific Coast. But by the time Spain built a fort on Vancouver Island, British explorer James Cook had visited Nootka Sound and mapped the coast. British and American traders also began settling there.

In 1793, Alexander Mackenzie crossed the continent. He reached the Pacific Ocean, becoming the first person to cross North America north of Mexico.

In 1846, the Oregon Treaty set the border between the United States and western British North America at the 49th parallel. By 1857, rumors of gold in the Fraser River area spread. Thousands of men rushed to the region, starting the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush.

Governor James Douglas had to establish British authority over this new population. To do this, the Crown colony of British Columbia was created on August 2, 1858. Douglas signed some treaties with First Nations on Vancouver Island but did not recognize others. In 1866, British Columbia joined with the Colony of Vancouver Island.

By the mid-1850s, politicians in the Province of Canada thought about expanding westward. They questioned the Hudson's Bay Company's control over Rupert's Land. They sent expeditions to learn about the geography and climate of the region.

Trade with the United States

In 1854, Lord Elgin, the Governor General of British North America, signed an important trade agreement with the United States. This agreement lasted for ten years until the American government ended it in 1865.

Confederation: Forming a New Country

Governing the United Province of Canada after 1840 was difficult. It required balancing the interests of French and English-speaking people, and Catholics and Protestants. John A. Macdonald became a leader who could manage this task in the 1850s. He formed alliances with George-Étienne Cartier, a leader of the French Canadian bleus, and George Brown, a reformer.

Macdonald realized that Canada's best chance to avoid being taken over by the United States was to form a working federation. A group from the Canadas went to a conference in 1864 in Charlottetown. Representatives from the Maritimes were already there to discuss joining Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island.

This led to another conference in Quebec City. The Seventy-Two Resolutions from the 1864 Quebec Conference laid out a plan to unite British colonies in North America into a federation. Most provinces in Canada adopted these resolutions. They became the basis for the London Conference of 1866, which led to the creation of the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867.

Confederation happened for several reasons:

- Britain wanted Canada to defend itself.

- The Maritimes needed railroad connections, which were promised.

- British-Canadian nationalism aimed to unite the lands into one country with English language and British culture.

- Many French-Canadians saw a chance to have political control within a new, mostly French-speaking Quebec.

- There were fears that the U.S. might expand northward after the United States Civil War.

- Politically, people wanted to expand responsible government and end the legislative problems between Upper and Lower Canada.

Even Queen Victoria supported the idea, thinking it might be best for Canada to become an independent kingdom. In the end, Canada became a Dominion under the British Crown. It was a new beginning, but not everyone was happy. Some saw Confederation as a way forward, while others, like a newspaper in Nova Scotia, announced the "death of the free and enlightened Province of Nova Scotia."

See also

- Heritage Minutes

- History of Canada

- Former colonies and territories in Canada

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |