Expulsion of the Acadians facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Expulsion of the Acadians |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of French and Indian War | |||||||

St. John River Campaign: "A View of the Plundering and Burning of the City of Grimross" (1758) Watercolor by Thomas Davies |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|||||||

The Expulsion of the Acadians, also known as the Great Upheaval, was a time when the British forcibly removed the Acadian people from their homes. This happened in what is now Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and parts of Maine. This area was historically known as Acadia. Thousands of people died during this event.

The Expulsion took place between 1755 and 1764, during the French and Indian War. This war was the North American part of the larger Seven Years' War. The British military wanted to defeat New France.

At first, the British sent Acadians to the Thirteen Colonies. After 1758, they sent more Acadians to Britain and France. Out of about 14,100 Acadians, around 11,500 were deported. Sadly, at least 5,000 of them died from sickness, hunger, or shipwrecks. Families were forced from their homes and farms. Their houses were burned, and their land was given to new settlers who were loyal to Britain.

In 1710, the British captured Port Royal, the capital of Acadia. The 1713 Treaty of Utrecht gave Acadia to Great Britain. However, the Acadians did not want to sign an oath of loyalty to Britain without conditions. Over the years, some Acadians helped the French military against the British. They also supplied French forts like Louisbourg and Fort Beauséjour. Because of this, the British decided to remove the Acadians. They wanted to stop any future military threat and cut off supplies to the French forts.

The British governor, Charles Lawrence, ordered the expulsion. He did not separate Acadians who were neutral from those who had fought. In the first wave, Acadians went to other British colonies in North America. In the second wave, they went to Britain and France. From there, many moved to Spanish Louisiana, where they became known as "Cajuns". Some Acadians first fled to French areas like Canada, Île Saint-Jean (now Prince Edward Island), and Île Royale (now Cape Breton Island). During the second wave, these Acadians were also captured or deported.

The Expulsion helped the British achieve their military goals. They destroyed the fortress of Louisbourg and weakened the Miꞌkmaq and Acadian militias. But it also caused great suffering for many civilians and harmed the region's economy. On July 11, 1764, the British government allowed Acadians to return to British lands in small groups. They had to promise full loyalty to Britain. Today, Acadians mostly live in eastern New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Northern Maine. The American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a famous poem called Evangeline in 1847. It told the story of a fictional Acadian character and helped people learn about the expulsion.

Contents

Why the Expulsion Happened

After Britain took control of Acadia in 1713, the Acadians did not want to sign an unconditional promise of loyalty to the British king. Instead, they agreed to an oath that said they would remain neutral. They worried that signing a full oath might force Acadian men to fight against France. They also feared it would upset their Miꞌkmaq neighbors and allies. This could put their villages at risk of attack.

Some Acadians refused the oath because they were against the British. Historians note that some Acadians were called "neutral" even when they were not. By the time of the Expulsion, Acadians and the Wabanaki Confederacy had a long history of resisting British rule in Acadia. The Miꞌkmaq and Acadians were allies because of their shared Catholic faith and many marriages between them. Even after the British conquest, the Wabanaki Confederacy, especially the Miꞌkmaq, had strong military power in Acadia. They resisted the British, and Acadians often joined them. French priests in the region often supported these efforts. The Wabanaki Confederacy and Acadians fought against the British Empire in six wars over 75 years.

The Seven Years' War Begins

In 1753, French troops from Canada moved south and took control of the Ohio Valley. Britain protested, claiming Ohio for itself. The war officially began on May 28, 1754. A British patrol led by George Washington killed a French officer and some of his men. In response, the French and Native Americans defeated the British at Fort Necessity.

In Acadia, Britain's main goal was to capture the French forts at Beauséjour and Louisbourg. They also wanted to stop future attacks from the Wabanaki Confederacy, French, and Acadians on the New England border. The British saw the Acadians' loyalty to the French and the Wabanaki Confederacy as a military threat. Governor Charles Lawrence and the Nova Scotia Council believed that Acadian civilians had helped the French and fought against the British.

After the British captured Beauséjour, they planned to capture Louisbourg. Part of this plan was to cut off trade to the fortress. This would weaken the fort and the French's ability to supply the Miꞌkmaq. Historian Stephen Patterson says that cutting off supplies was key to ending French power in the region. Lawrence realized he could reduce the military threat and weaken Fortress Louisbourg by deporting the Acadians. This would cut off their supplies to the fort. During the expulsion, French Officer Charles Deschamps de Boishébert led the Miꞌkmaq and Acadians in a guerrilla war against the British.

British Deportation Campaigns

The British Lieutenant Governor, Charles Lawrence, and the Nova Scotia Council decided to deport the Acadians on July 28, 1755. This happened after the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of loyalty to Britain. The British deportation campaigns began on August 11, 1755. Throughout the expulsion, Acadians and the Wabanaki Confederacy continued to fight against the British.

Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755)

The first wave of the expulsion started on August 10, 1755. This was during the Bay of Fundy Campaign of the French and Indian War. The British ordered the expulsion after the Battle of Beausejour (1755). The campaign began at Chignecto and then moved to Grand-Pré, Piziquid (Falmouth/Windsor, Nova Scotia), and finally Annapolis Royal.

On November 17, 1755, George Scott led 700 troops to Memramcook. They attacked twenty houses, arrested the remaining Acadians, and killed two hundred livestock. This was to prevent the French from getting supplies. Many Acadians tried to escape the expulsion by going to the St. John and Petitcodiac rivers, and the Miramichi in New Brunswick. The British later cleared Acadians from these areas in campaigns in 1758.

Acadians and Miꞌkmaq resisted in the Chignecto region. They won the Battle of Petitcodiac (1755). In 1756, a group from Fort Monckton was ambushed. In April 1757, Acadian and Miꞌkmaw fighters raided Fort Edward and Fort Cumberland. They killed two men and took two prisoners. In July 1757, some Miꞌkmaq killed 23 and captured two of Gorham's rangers near Fort Cumberland.

In September 1756, 100 Acadians ambushed thirteen soldiers outside Fort Edward at Piziquid. Seven soldiers were captured. In April 1757, Acadian and Miꞌkmaw fighters raided a warehouse near Fort Edward. They killed thirteen British soldiers, took supplies, and burned the building.

The Acadians and Miꞌkmaq also fought in the Annapolis region. They won the Battle of Bloody Creek (1757). Acadians being deported on the ship Pembroke rebelled against the British crew. They took over the ship and sailed to land.

About 55 Acadians escaped the first deportation at Annapolis Royal. They went to the Cape Sable region in southwestern Nova Scotia. From there, they took part in many raids on Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. Acadians and Miꞌkmaq raided Lunenburg nine times over three years. Boishebert ordered the first Raid on Lunenburg (1756). In 1757, six people from the Brisson family were killed in the second raid. By May 1758, most people on the Lunenburg Peninsula had left their farms for safety.

Cape Sable Campaign

The Cape Sable campaign involved the British removing Acadians from what is now Shelburne County and Yarmouth County. In April 1756, Major Jedidiah Preble and his New England troops raided a settlement near Port La Tour. They captured 72 men, women, and children. In late summer 1758, Major Henry Fletcher led troops to Cape Sable. One hundred Acadians and Father Jean Baptistee de Gray surrendered. About 130 Acadians and seven Miꞌkmaq escaped. The Acadian prisoners were sent to Georges Island in Halifax Harbour.

In September 1758, Colonel Robert Monckton sent Major Roger Morris to deport more Acadians. On October 28, Morris's troops sent women and children to Georges Island. The men stayed behind to destroy their village. On October 31, they were also sent to Halifax. In spring 1759, Joseph Gorham and his rangers captured the remaining 151 Acadians. They arrived at Georges Island with them on June 29. In November 1759, these 151 Acadians were deported to Britain.

Île Saint-Jean and Île Royale Campaigns

The second wave of the expulsion began after the French lost the Siege of Louisbourg (1758). Thousands of Acadians were deported from Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Île Royale (Cape Breton Island). The Île Saint-Jean Campaign caused the most deaths among deported Acadians. The sinking of the ships Violet (with about 280 people) and Duke William (with over 360 people) led to the highest number of deaths during the expulsion. By this time, the British were sending Acadians directly to France, not to the Thirteen Colonies. In 1758, hundreds of Île Royale Acadians fled to refugee camps.

Petitcodiac River Campaign

The Petitcodiac River Campaign was a series of British military actions from June to November 1758. Its goal was to deport Acadians living along the river or those who had taken refuge there. Benoni Danks and Gorham's Rangers carried out this operation. On July 1, 1758, Danks pursued Acadians on the Petiticodiac. They reached present-day Moncton. Danks' Rangers ambushed about 30 Acadians led by Joseph Broussard dit Beausoleil. Three Acadians were killed, and others were captured. Broussard was badly wounded.

St. John River Campaign

Colonel Robert Monckton led 1,150 British soldiers to destroy Acadian settlements along the Saint John River. They reached the largest village, Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas (Fredericton, New Brunswick), in February 1759. Monckton was joined by New England Rangers. The British started at the mouth of the river, raiding Kennebecais and Managoueche (City of Saint John). They built Fort Frederick there. Then they moved upriver, raiding Grimross (Gagetown, New Brunswick), Jemseg, and finally Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas.

Lieutenant Hazen, a New England Ranger, engaged in harsh warfare against the Acadians. On February 18, 1759, Hazen and about fifteen men arrived at Sainte-Anne des Pays-Bas. The Rangers looted and burned the village, destroying 147 buildings, two Catholic churches, and many barns. They burned a large storehouse with food and killed 212 horses and other animals. They also burned the church. The leader of the Acadian militia on the St. John river, Joseph Godin-Bellefontaine, refused to swear an oath. The Rangers also took six prisoners.

Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign

In the Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign, British forces raided French villages along present-day New Brunswick and the Gaspé Peninsula coast. Sir Charles Hardy and Brigadier-General James Wolfe led the naval and military forces. After the Siege of Louisbourg (1758), Wolfe and Hardy led 1500 troops in nine ships to Gaspé Bay, arriving on September 5. From there, they sent troops to Miramichi Bay on September 12, Grande-Rivière, Quebec and Pabos on September 13, and Mont-Louis, Quebec on September 14. Over the next weeks, Hardy captured four ships, destroyed about 200 fishing vessels, and took about 200 prisoners.

Restigouche

Acadians took refuge along the Baie des Chaleurs and the Restigouche River. Boishébert had a refugee camp at Petit-Rochelle. In late 1761, Captain Roderick Mackenzie and his force captured over 330 Acadians at Boishebert's camp.

Halifax

After the French captured St. John's, Newfoundland, on June 14, 1762, Acadians and Native people became more confident. They gathered in large numbers. Officials were worried when Native people gathered near Halifax and Lunenburg, where many Acadians also lived. The government organized the expulsion of 1,300 people and sent them to Boston. However, the Massachusetts government refused to let the Acadians land and sent them back to Halifax.

Miꞌkmaw and Acadian resistance was also seen in the Halifax region. Acadian Pierre Gautier led Miꞌkmaw warriors from Louisbourg on three raids against Halifax Peninsula in 1757. In each raid, Gautier took prisoners. Their last raid was in September, where Gautier and four Miꞌkmaq killed two British men.

In July 1759, Miꞌkmaq and Acadians killed five British people in Dartmouth. By June 1757, settlers had to leave Lawrencetown because of too many Native raids. In nearby Dartmouth, in spring 1759, another Miꞌkmaw attack happened at Fort Clarence. Five soldiers were killed. Before the deportation, there were about 14,000 Acadians. Most were deported, but some escaped to Quebec, or hid among the Miꞌkmaq or in the countryside.

Maine

In what is now Maine, the Miꞌkmaq and the Maliseet raided many New England villages. In April 1755, they raided Gorham, killing two men and a family. They then appeared in New Boston (Gray) and destroyed farms in nearby towns. On May 13, they raided Frankfort (Dresden), where two men were killed. The same day, they raided Sheepscot (Newcastle) and took five prisoners. Two people were killed in North Yarmouth on May 29. They also took prisoners at Fort Halifax and Fort Shirley (Dresden).

On August 13, 1758, Boishebert left Miramichi, New Brunswick with 400 soldiers, including Acadians. They marched to Fort St. George (Thomaston) and tried to attack the town without success. They also raided Munduncook (Friendship), where they wounded eight British settlers and killed others. This was Boishébert's last Acadian expedition. From there, he and the Acadians went to Quebec and fought in the Battle of Quebec (1759).

Where Acadians Were Sent

| Colony | Number of exiles |

|---|---|

| Massachusetts | 2,000 |

| Virginia | 1,100 |

| Maryland | 1,000 |

| Connecticut | 700 |

| Pennsylvania | 500 |

| North Carolina | 500 |

| South Carolina | 500 |

| Georgia | 400 |

| New York | 250 |

| Total | 6,950 |

| Britain | 866 |

| France | 3,500 |

| Total | 11, 316 |

In the first wave of the expulsion, most Acadians were sent to rural communities in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and South Carolina. They often refused to stay where they were placed. Many moved to port cities, forming poor, French-speaking Catholic neighborhoods. The British authorities did not like this. They were also worried that some Acadians might move north to French-controlled areas. Because the British felt their plan to send Acadians to the Thirteen Colonies had failed, they deported them to France in the second wave.

Maryland

About 1,000 Acadians went to the Colony of Maryland. They lived in a part of Baltimore called French Town. Irish Catholics there were said to have helped the Acadians, taking orphaned children into their homes.

Massachusetts

Around 2,000 Acadians landed in the Colony of Massachusetts. Some families were sent to the Province of Maine. For four long winter months, William Shirley, who ordered their deportation, did not let them leave the ships. As a result, half of them died from cold and hunger on board. Some men and women were forced into servitude or labor. Children were taken from their parents and given to different families in Massachusetts.

Connecticut

The Colony of Connecticut prepared for 700 Acadians. Like Maryland, the Connecticut government said that Acadians should be "made welcome, helped and settled."

Pennsylvania and Virginia

The Colony of Pennsylvania took in 500 Acadians. They arrived unexpectedly and had to stay on their ships for months. The Colony of Virginia refused to accept the Acadians because they were not given notice. They were held at Williamsburg, where hundreds died from disease and hunger. They were then sent to Britain and held as prisoners until the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

Carolinas and Georgia

Acadians who had resisted the British the most were sent to the southernmost colonies (the Carolinas and the Colony of Georgia). About 1,400 Acadians settled there and worked on plantations.

Many Acadians in Georgia received passports from Governor Reynolds. Without these, travel between colonies was not allowed. Once they reached the Carolinas, those colonies also gave passports to Acadians in their areas. Acadians were also given two ships. After many problems with the ships, some Acadians returned to the Bay of Fundy. They were captured and imprisoned along the way. Only 900 managed to return to Acadia.

France and Britain

After the Siege of Louisbourg (1758), the British began sending Acadians directly to France. Some Acadians never reached France. Almost 1,000 died when the ships Duke William, Violet, and Ruby sank in 1758. These ships were traveling from Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) to France. About 3,000 Acadian refugees eventually gathered in French port cities like Nantes. Many Acadians sent to Britain lived in crowded warehouses and suffered from diseases. Others were allowed to live normal lives in communities. In France, 78 Acadian families moved to Belle-Île-en-Mer after the Treaty of Paris. About 1,500 Acadians accepted an offer from King Louis XV for land in the Poitou province. They called their new home La Grande Ligne ("The Great Road"). But the land was not fertile, and most of them left by the end of 1775.

What Happened to the Acadians?

Louisiana

Acadians left France to settle in Louisiana, which was then a Spanish colony. The British did not deport Acadians to Louisiana. Louisiana was given to Spain in 1762. Because France and Spain had good relations and shared the Catholic religion, some Acadians chose to pledge loyalty to the Spanish government. Soon, Acadians became the largest ethnic group in Louisiana. They first settled along the Mississippi River. Later, they moved to the Atchafalaya Basin and the prairie lands to the west. This region was later renamed Acadiana.

Some Acadians were sent to colonize places in the Caribbean, like French Guiana, or the Falkland Islands. These efforts were not successful. Other Acadians moved to places like Saint-Domingue, but they fled to New Orleans after the Haitian Revolution. Louisiana's Acadian population helped create the modern Cajun population. The French word "Acadien" changed into "Cadien," which later became the English word "Cajun."

Nova Scotia

On July 11, 1764, the British government allowed Acadians to return to British lands in small, separate groups. They had to take a full oath of loyalty. Some Acadians returned to Nova Scotia (which included present-day New Brunswick). Under the deportation orders, Acadian land had been taken by the British crown. The returning Acadians no longer owned land. Starting in 1760, much of their former land was given to new settlers. Because there wasn't much farmland available, many Acadians became fishermen on the west coast of Nova Scotia, known as the French Shore. The British authorities scattered other Acadians in groups along the coasts of eastern New Brunswick and the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. It wasn't until the 1930s that Acadians became less economically disadvantaged.

Remembering the Expulsion

In 1847, the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow published a long poem about the expulsion called Evangeline. It tells the story of a fictional character named Evangeline and became very popular, making the expulsion widely known. The Evangeline Oak is a tourist spot in Louisiana. The song "Acadian Driftwood" by The Band (1975) also tells the story of the Great Upheaval. Antonine Maillet wrote a novel, Pélagie-la-Charrette, about what happened after the Expulsion. It won a major French literary prize in 1979.

Grand-Pré Park is a National Historic Site of Canada in Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia. It is a monument to the expulsion and has a memorial church and a statue of Evangeline. The song "1755" was written by American Cajun fiddler and singer Dewey Balfa. In 2018, Canadian historian A. J. B. Johnston wrote a young adult novel called The Hat, inspired by events at Grand-Pré in 1755.

In December 2003, Governor General Adrienne Clarkson, representing Queen Elizabeth II, acknowledged the expulsion. She did not apologize for it. She named July 28 as "A Day of Commemoration of the Great Upheaval." This official statement ended one of the longest legal cases in British history. It began in 1760 when Acadian representatives first complained about losing their land, property, and livestock. December 13, the day the Duke William sank, is remembered as Acadian Remembrance Day. There is a museum in Bonaventure, Quebec, dedicated to Acadian history and culture, with a detailed display of the Great Uprising.

Images for kids

-

St. John River Campaign: "A View of the Plundering and Burning of the City of Grimross" (1758)

-

Charles Lawrence, British Army officer and Governor of Nova Scotia.

-

Major Jedidiah Preble.

-

Raid on Miramichi Bay – Burnt Church Village by Captain Hervey Smythe (1758).

-

Monument to Imprisoned Acadians on Georges Island (background), Bishops Landing, Halifax.

-

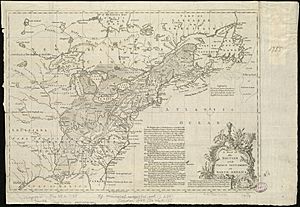

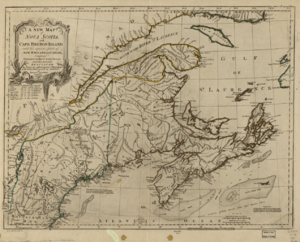

This map by Thomas Jefferys (1755) shows Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island after the "great upheaval."

See also

In Spanish: Expulsión de los acadianos para niños

In Spanish: Expulsión de los acadianos para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |