Atchafalaya Basin facts for kids

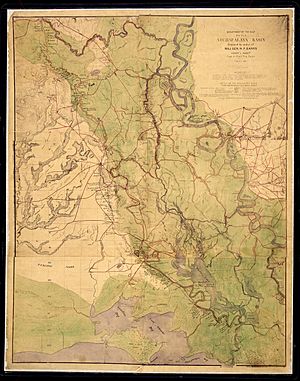

The Atchafalaya Basin, also known as the Atchafalaya Swamp, is the largest swampy wetland in the United States. It's located in south-central Louisiana. This amazing area is a mix of wetlands and a river delta where the Atchafalaya River meets the Gulf of Mexico. The river flows from near Simmesport in the north down to the Morgan City area in the south.

The Atchafalaya Basin is special because its delta system is still growing. About 70% of the basin is forest, and 30% is marsh and open water. It has the largest continuous area of forested wetlands in the lower Mississippi River valley. It's famous for its beautiful cypress-tupelo swamps, which cover about 260,000 acres (105,218 hectares). This is the biggest remaining coastal cypress forest in the United States.

Contents

Exploring the Atchafalaya Basin's Unique Landscape

The Atchafalaya Basin is full of bayous, bald cypress swamps, and marshes. As you move closer to the Gulf of Mexico, the water becomes a mix of fresh and salty, called brackish water. Finally, you reach the Spartina grass marshes where the Atchafalaya River flows into the Gulf.

This basin is huge, about 20 miles (32 km) wide and 150 miles (241 km) long. It covers about 1.4 million acres (5,666 km²) and is the largest wetland in the United States. It has vast areas of bottomland hardwoods, swamps, bayous, and lakes. Many animals call this place home, including the Louisiana black bear (Ursus americanus luteolus). This bear has been on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's threatened list since 1992.

Roads and Wildlife Protection

Few roads cross the basin, and they usually follow the tops of levees. Interstate 10 crosses the basin on a long, elevated bridge, which is about 18.2 miles (29.3 km) long. This bridge connects Grosse Tete, Louisiana to Henderson, Louisiana.

To protect the amazing wildlife here, the Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge was created in 1984. It helps plant communities grow for endangered species, waterfowl, migratory birds, and alligators.

How the Atchafalaya Basin Was Formed and Managed

The Atchafalaya Basin has always been connected to the Mississippi River. Over thousands of years, the Mississippi River helped shape the land in south Louisiana by depositing sediment. The Atchafalaya Basin is a low-lying area between the natural paths of the Mississippi River.

Controlling the Mighty Rivers

To prevent major floods, people built large levees around the Atchafalaya Basin. These levees were finished in the 1940s. They help direct floodwaters from the Mississippi River south towards Morgan City and then into the Gulf of Mexico.

In the mid-1800s, people made changes to the Atchafalaya River. They removed a huge log jam and dredged the river. This connected the Atchafalaya River more directly to the Mississippi River. Since 1963, a special structure called the Old River Control Structure makes sure that about 30% of the water from the Mississippi, Red, and Black rivers flows into the Atchafalaya. This helps manage the water flow and prevent the Mississippi River from changing its main course.

When there are very big floods, the US Army Corps of Engineers might open the Morganza Spillway. This helps relieve pressure on the levees along the Mississippi River. For example, on May 13, 2011, the Morganza Spillway was opened to protect cities like New Orleans from severe flooding. This water then flows into the Atchafalaya Basin between its protective levees.

Protecting the Atchafalaya Swamps: Challenges and Changes

The way we manage floods in the Atchafalaya and Mississippi rivers has become a big topic. The US Geological Survey (USGS) reports that the salt marshes in the Mississippi River delta are shrinking by about 29 square miles (75 km²) each year. The Atchafalaya River Deltas are one of the few places along the Louisiana Gulf Coast where new land is actually forming.

How Human Actions Changed the Swamps

In the early 1900s, the Atchafalaya River Basin was chosen as a "spillway" for Mississippi River floods. To protect farms and towns, new levees were built. These levees separated the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway from much of its original swamp land. A main channel was also dredged, connecting the basin to the sediment-rich Mississippi River.

Over time, the amount of open water in the basin has decreased. From 1850 to 1950, open water shrank from 490 km² (189 sq mi) to 290 km² (112 sq mi). By 2005, it was down to 190 km² (73 sq mi). The plan was for 30% of the Atchafalaya River's flow to spread out into the floodplain. However, due to changes in the riverbed, only about 13% of the flow now spreads out. This reduced flow, along with lots of decaying plants and warm water, has led to areas with low oxygen in the water. This can make it harder for fish and other aquatic life to survive.

Impact of Canals

Between 1960 and 1980, many canals were dug in the basin for oil and gas exploration. These large canals, often 30-50 meters (98-164 ft) wide and 2-3 meters (7-10 ft) deep, changed how water flowed through the swamps. Areas that were once protected from sediment suddenly became connected to the river. This caused them to fill up with sediment very quickly. The USGS found that sediment could build up as much as 30 cm (12 inches) per year where these canals met open water. The dirt dug out from these canals was piled up next to them, further blocking the natural water flow across the floodplain.

The Lost Community of Bayou Chene

From 1830 to 1953, a lively community called Bayou Chene thrived deep within the Atchafalaya Basin. It was a hub for logging, hunting, trapping, and fishing. Today, Bayou Chene is buried under many feet of silt, one of several communities lost to the changing landscape of the basin.

Early Settlers and Growth

The first people to live in the Bayou Chene area were the native Chitimacha tribe. They had important villages there, like the Village of Bones and the Cottonwood Village. An early French explorer, C.C. Robin, described the area in 1803 as a "magnificent lake" surrounded by tall trees, a truly "enchanting sight."

By 1841, about 15 to 20 families were farming along "Oak Bayou," or Bayou Chene. The population grew quickly, reaching 675 residents by 1860. By the 1870s, most people in Bayou Chene worked in logging, cutting down bald cypress, tupelo, and other trees from the bottomland forests.

In the early 1900s, Bayou Chene became the center of the basin's cypress and fur industries. It was also home to many of the 1,000 full-time fishermen who worked in the swamp. Gwen Roland, whose family lived there, described how everyone relied on the basin's waters for everything, even transportation. She wrote about their special skiffs, designed to float high and steer quickly through the shallow waters.

The End of Bayou Chene

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 almost demolished the community. Floodwaters rose seven feet above the natural levees and covered Bayou Chene for weeks. Local stories say a village goat survived in the Methodist Church by eating hymnals and wallpaper!

The Great Depression was tough, but many residents found work on the massive flood control projects led by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. After the 1927 flood, the entire Atchafalaya Basin was officially named a floodway. A series of man-made levees were built, which forever changed the flooding patterns. More flooding in 1937 caused many residents to move their homes to higher ground. However, even these efforts couldn't protect the community from annual floods.

After years of rising waters, the community of Bayou Chene came to an end. The United States Post Office there closed in 1952. Most former residents moved to towns on the edges of the basin, like New Iberia, St. Martinville, and Breaux Bridge. Today, very little remains of this swamp community, hidden beneath the murky waters of the Atchafalaya.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Cuenca Atchafalaya para niños

In Spanish: Cuenca Atchafalaya para niños

- Mississippi River Delta

- Wetlands of Louisiana

- List of Louisiana rivers

- Atchafalaya National Heritage Area

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |