Chitimacha facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1250 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Cajun French, Chitimacha (No fluent speaker. Successful at reviving the language.) | |

| Religion | |

| Catholicism, other |

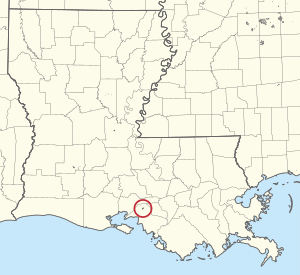

The Chitimacha (pronounced CHIT-i-mə-shah) are a federally recognized tribe of Native American people. They live in the U.S. state of Louisiana. Their main home is on their reservation in St. Mary Parish. This area is near Charenton on Bayou Teche.

They are the only Indigenous group in Louisiana who still control some of their original land. This land is part of the Atchafalaya Basin. This basin is known as one of the richest natural areas on the continent. In 2011, there were about 1,100 Chitimacha people.

The Chitimacha people historically spoke the Chitimacha language. This language is unique and not related to others. The last two native speakers passed away in the 1930s. However, the tribe has been working hard since the 1990s to bring their language back to life. They use notes and recordings made by a linguist named Morris Swadesh from around 1930.

They have started special classes where children and adults learn the language by speaking only Chitimacha. In 2008, they teamed up with Rosetta Stone. Together, they created software to help people learn the language. Each Chitimacha family received a copy to use at home. The tribe has used money from their gambling businesses to support education and keep their culture alive. They have opened a tribal museum and an office for preserving history. They also continue to work on restoring their language.

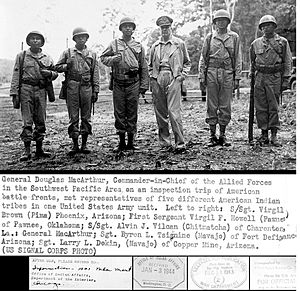

The Chitimacha are one of four federally recognized tribes in Louisiana. This means the U.S. government officially recognizes them. Louisiana also recognizes several other tribes that do not have federal recognition. In the late 1900s, Louisiana had the third-largest Native American population in the eastern United States.

A Look Back: Chitimacha History

The Chitimacha people and their ancestors lived in the Mississippi River Delta area of south-central Louisiana for thousands of years. This was long before Europeans arrived. Old stories say that the Chitimacha land was marked by four special trees.

Archaeological discoveries suggest the Chitimacha have lived in Louisiana for about 6,000 years. Before that, they moved into the area from west of the Mississippi River. The Chitimacha say their name, Pantch Pinankanc, means "men altogether red," which also means warrior.

Chitimacha Sub-Tribes and Their Homes

The Chitimacha were once divided into four main groups. These were the Chawasha, Chitimacha, Washa, and Yagenachito. The Choctaw people gave these names based on where each group lived. For example, Chawasha means "Raccoon Place" in Choctaw. Washa means "Hunting Pace," and Yaganechito means "Big Country."

The Chitimacha built their villages deep within the many swamps, bayous, and rivers of the Atchafalaya Basin. This area is very rich in natural resources. The watery landscape provided a natural defense, making their villages very safe. They did not need to build strong forts.

Their villages were quite large, with about 500 people living in each. Homes were made from materials found nearby. They typically built walls from poles and covered them with mud or palmetto leaves. The roofs were thatched with plant materials.

Daily Life and Skills

The Chitimacha grew many different crops. Farming provided most of their food. Women were in charge of planting and harvesting. They were skilled farmers, growing many types of corn, beans, and squash. Corn was their main crop. They also gathered wild foods and nuts.

Men hunted animals like deer, turkey, and alligator. They also caught fish. They stored extra crops in raised buildings called granaries for the winter.

Living by the water, the Chitimacha made dugout canoes for travel. These boats were carved from large cypress logs. The biggest canoes could carry up to forty people. To get stones for arrowheads and tools, they traded crops with tribes to the north. They also developed weapons like the blow gun and cane dart. They even used fish bones for arrowheads.

The Chitimacha had a unique custom of flattening the foreheads of their baby boys. They would gently bind their heads as infants to shape their skulls. Adult men usually wore their hair long. They were also very skilled at tattooing. They often covered their faces, bodies, arms, and legs with designs. Because of the hot, humid weather, men usually wore only a breechcloth, and women wore a short skirt.

Family and Society

Like many Native American groups, the Chitimacha had a matrilineal kinship system. This means that property and family lines were passed down through the mother. Hereditary male chiefs, who led the tribe until the early 1900s, came from the mother's side of the family. Female elders had to approve them. Children belonged to their mother's family and clan. They also received their social standing from her.

The Chitimacha also welcomed and adopted people from other groups. When Chitimacha women had children with European traders, these children were considered part of the mother's family. They were raised as Chitimacha.

The Chitimacha had a strict class system with nobles and commoners. These two classes were so different that they even spoke different versions of the language. Marriage between the classes was not allowed.

European Contact and Challenges

When Christopher Columbus arrived in America, historians believe there were about 20,000 Chitimacha people. Even though the Chitimacha had almost no direct contact with Europeans for two more centuries, they suffered greatly. They caught Eurasian infectious diseases like measles, smallpox, and typhoid fever from other Native Americans who had traded with Europeans. Like other Native Americans, the Chitimacha had no natural protection against these new diseases. Many died in epidemics.

By 1700, when the French began to settle in the Mississippi River Valley, the number of Chitimacha had dropped sharply. The French described the Chitimacha villages as self-governing groups. A Grand Chief led all the groups, but they mostly managed themselves.

Between 1706 and 1718, the Chitimacha fought a long, difficult war with the French. The French had better weapons and nearly destroyed the eastern Chitimacha. Those who survived were moved by the French authorities. They were settled farther north along the Mississippi River, away from the Gulf of Mexico. This is where they live today. Diseases caused more deaths than the war. This led to major social problems and the defeat of the people. By 1784, the total number of Chitimacha had fallen to 180. In the early 1800s, a small group joined the Houma people of Louisiana.

In the late 1700s, the British moved the Acadians (French colonists from Canada) to Louisiana. This happened after Britain defeated France in a war. The Acadians' descendants became known as Cajuns. They also put pressure on the Chitimacha by taking over their land.

Over time, some Chitimacha married Acadians and slowly adopted their way of life. They even became Catholic. Others welcomed Europeans into Chitimacha society. Children born to Chitimacha women and European men were considered part of their mother's families. They were usually raised within the Indigenous culture.

In the mid-1800s, the Chitimacha sued the United States to confirm their land rights. The federal government officially set aside 1,062 acres in St. Mary Parish as Chitimacha land.

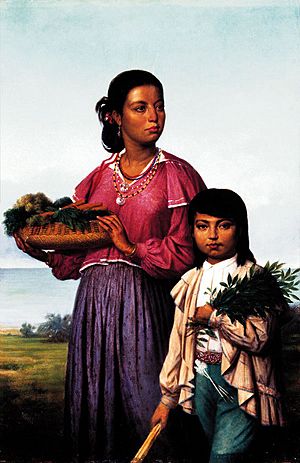

Chitimacha women are known for weaving beautiful baskets from rivercane. They traditionally use three colors: yellow, red, and black. They have made and sold baskets for centuries, which has been an important part of their economy. Ada Thomas, a basket maker skilled in the double-weave technique, was honored in 1983 for her work.

Modern Times: 20th Century to Today

The 1900 federal census counted six Chitimacha families, with 55 people in total. In 1910, there were 69 Chitimacha recorded. Nineteen of their children attended the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. This school, like other Indian boarding schools, aimed to make Native American children adopt mainstream U.S. culture. They were forced to speak English and were separated from their families for long periods. This stopped the passing down of native languages.

The tribe faced financial difficulties in the early 1900s. Sometimes, members had to sell land because they could not pay taxes. Sarah Avery McIlhenney, a local supporter whose family made Tabasco, helped the Chitimacha women. She bought their last 260 acres of land in 1915 and then gave it to the tribe. The tribe then gave the land to the federal government. The government agreed to hold it in trust as a reservation for the tribe. McIlhenny also encouraged the government to officially recognize the Chitimacha as a tribe. The Department of Interior granted this recognition in 1917.

The Chitimacha were the first Indigenous group still living in Louisiana to gain federal recognition. Most Native Americans in the Southeast had been moved from their lands to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) in the 1830s. The tribe received some money and benefits because of this official recognition. However, their population continued to decline. By 1930, there were only 51 Chitimacha people recorded.

Since that low point in the early 1900s, the population has grown as the people have recovered. Men found better jobs working in Louisiana's oil fields. In the early 2000s, the tribe reported having over 900 enrolled members. The 2000 census showed 409 people living on the Chitimacha Indian Reservation. Of these, 285 said they were only of Native American ancestry.

The reservation is located in the northern part of Charenton. It is in St. Mary Parish on Bayou Teche, within the rich Atchafalaya Basin. The Chitimacha are the only Indigenous people in Louisiana who still control some of their traditional lands. Like many Native American tribes, the Chitimacha now manage their children's education. They have established the Chitimacha Tribal School on the reservation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs supports this school.

The Tribal Council is currently working with the United States government. They are seeking payment for lands taken in the past. Using money from their casino, the Chitimacha have bought more land to be held in trust for their reservation. They now control 1,000 acres. They have built a casino, a school, a fish processing plant, and a tribal museum on their reservation.

Language Revival Efforts

The Chitimacha language became extinct after the last two native speakers, Benjamin Paul and Delphine Ducloux, passed away in the 1930s. However, a young linguist named Morris Swadesh worked with Paul and Ducloux in the 1930s. He recorded their language and stories. He took many notes to save the language and its traditional tales. Most Chitimacha today speak Cajun French and English.

With money from their casino, the tribe has started many cultural activities. These include an office for preserving tribal history and language immersion classes. They also have a tribal museum and a project to help river cane grow again on tribal lands. This cane is used for weaving traditional baskets. In the early 1990s, the American Philosophical Society Library contacted the tribe. They said they had Swadesh's papers, which included many notes on the Chitimacha language. These notes even had a draft grammar book and dictionary.

A small team was formed to learn the language quickly. They began preparing materials to teach it, like storybooks. Language immersion classes were started for children at the tribal school.

In 2008, the tribe partnered with Rosetta Stone. Their goal was to create software to document the language and provide teaching materials. Each Chitimacha household received a copy of the software. This was to help families learn the language and encourage children to speak it at home. This project is also creating a complete dictionary and a grammar guide for the language.

Chitimacha Government

The Chitimacha re-established their government under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. This act was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal" for Native Americans. In the 1950s, the tribe successfully resisted efforts to end their official status as a tribe. Such a move would have ended their relationship with the federal government.

In 1971, they adopted a new written constitution. They have an elected government with a Tribal Council of five members. These members serve two-year terms. Three members are elected from specific areas, and two are elected from the tribe as a whole.

Who Can Be a Member?

Like all federally recognized tribes, the Chitimacha have their own rules for who can be a member. Their constitution states that members must have a certain amount of Chitimacha ancestry. They must also be able to show they are directly related to someone on one of two official lists:

- The Annuity Pay Roll of 1926, kept by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or

- The Revised census roll of June 1959, kept at the Choctaw Indian Agency in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Also, a future member must prove they have at least one-sixteenth (1/16) Chitimacha Indian ancestry. This is like having one great-great-grandparent who was Chitimacha. Children born since 1971 (when the tribe adopted their Constitution) who have at least one-sixteenth (1/16) Chitimacha Indian blood are also eligible for membership.

Chitimacha in Media

- Native Waters: A Chitimacha Recollection (2011) is a documentary film. It was directed and produced by Laudun for Louisiana Public Broadcasting. It won an award in 2012.

Notable Chitimacha People

- Christine Navarro Paul (1874–1946), a skilled basket maker.

- Ada Thomas (1924–1992), also a famous basket maker.

|

See also

In Spanish: Chitimacha para niños

In Spanish: Chitimacha para niños