Christine Navarro Paul facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Christine Navarro Paul

|

|

|---|---|

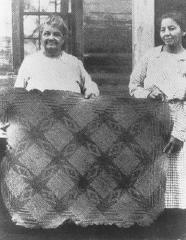

Christine Navarro Paul (left) in 1908 displaying a woven cane mat outside her house

|

|

| Born | December 28, 1874 Charenton, Louisiana, U.S.

|

| Died | 1946 (aged 71–72) |

| Occupation | Chitimacha basket maker |

| Spouse(s) | Benjamin Paul |

| Parent(s) | Joseph Auguste Navarro and Augustine Marguerite Pladner |

Christine Navarro Paul (born December 28, 1874 – died 1946) was a very important member of the Native American Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana. She was famous for making beautiful baskets and for teaching others how to make them.

When she was in her 20s, Christine started leading Chitimacha women to make and sell woven baskets. These baskets were made from a plant called wild river cane. Selling these baskets helped the tribe in many ways. It gave them money and helped them gain support from others.

Christine worked with several non-Native American women. These women helped her sell the baskets to people outside the tribe. The friendships she made with these women also helped the Chitimacha tribe get more support.

Christine and her husband, Benjamin Paul, who was the Chief of the Chitimacha, cared for children in their community. They looked after orphans and other children who needed help. Christine also worked hard to get a school built for Chitimacha children. When the school finally opened in 1935, she became the main teacher for basket weaving. This was very important because it made sure that the special skills of making Chitimacha baskets would continue for future generations. Christine Navarro Paul passed away in 1946.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Older Chitimacha women taught younger women how to weave baskets. They used wild river cane, also known as Arundinaria gigantea, to make these baskets. This helped the families earn extra money. The women also grew food in gardens and collected wild plants.

Christine's mother died when she was seven years old. Her father passed away when she was nine. She probably lived with her step-mother after that. Christine went to a nearby Catholic school. There, she learned to speak English. This skill was very helpful later in her life. It allowed her to talk with the non-Native women who helped sell the Chitimacha baskets.

Family and Community Work

Christine married Benjamin Paul. His father, John Paul, was the chief of the Chitimacha tribe before him. Like other men in the tribe, Benjamin worked on sugarcane farms during certain seasons. He also cut cypress trees and hunted and fished for food. When his father died, Benjamin Paul became the chief of the Chitimacha tribe.

Christine and Benjamin did not have their own children. However, they took care of many orphans and other children who needed help in their community. Sara McIlhenny, one of Christine's friends, wrote that "The needy, sick and orphans all turn for help to the Chief and his wife."

Christine was a key person for the Chitimacha people. She helped them communicate with others throughout her life. Her husband told the Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs that his wife "is the one doing the Indian’s business." This shows how important she was in handling the tribe's affairs.

In 1908, a person who studies cultures, Mark R. Harrington, interviewed Christine Paul. Her granddaughter, Ada Thomas, also became a famous basket maker.

Chitimacha Basket Making

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands are well-known for making baskets and mats from river cane. The Chitimacha people are especially known for their detailed and curved designs in their river cane baskets. These baskets were not just useful items. They also helped show that the Chitimacha tribe was a special and unique Native American nation.

Christine likely learned her weaving skills from Miss Clara Darden. She was one of the older women in the tribe and a very skilled weaver. To make the baskets, they collected wild river cane. This cane, called Arundinaria gigantea, used to be easy to find but became harder to get.

They would cut the cane while it was still green. Then, they split and peeled it into thin strips called splints. These splints were dried and then dyed with natural dyes. They used colors like yellow, black, or red. It took many weeks to prepare the splints before they could even start weaving.

The baskets were made in 16 or more different patterns. They came in many shapes, including mats, trays, bowls, and boxes with lids. A newspaper reporter once saw a large trunk basket and a cigar case made by Christine Paul.

Selling the Baskets

In 1899, Mary McIlhenny Bradford, from a well-known family on Avery Island, asked about buying Indian baskets. Three months later, Christine Paul wrote back to her, saying the basket was on its way. A non-Native man offered Christine $35 for the basket, but she sold it to Mary Bradford instead.

The basket Mary Bradford received was a large, lidded basket woven with a double layer. It took two women several weeks to make it. At that time, many people in the United States wanted real, well-made Native American crafts.

Mary and her older sister, Sara McIlhenny, created a large group of wealthy White women to help sell these baskets. Some people bought them for their own homes. Others wanted to add them to art collections or museums. The McIlhenny sisters felt they were helping to save a craft that was almost disappearing. They also wanted to support people who were struggling. The money from selling the baskets was very important for the Chitimacha community.

Christine was a member of the chief's family and could read and write English. This made her the main contact person with the McIlhenny sisters. She helped organize the orders for the baskets. Christine helped bring back basket making among the Chitimacha women. Mary McIlhenny Bradford helped with selling them. For example, she helped get the baskets shown at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Christine and the McIlhenny sisters communicated less often. However, in the 1930s, Christine and her sister-in-law Pauline Paul started working with another White woman. Her name was Caroline Coroneos Dorman. She was a writer and teacher who helped them continue selling their baskets. Caroline Dorman was also interested in the Chitimacha and other Native American tribes. In 1931, she wrote an article called “The Last of the Cane Basket Makers” for Holland’s, The Magazine of the South. This article helped people become interested again in Chitimacha baskets and their Native American culture.

Collections

Christine Navarro Paul's work is kept in the U.S. Department of the Interior Museum. The Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian has two unfinished, double-weave baskets made by her. These show how she built the baskets and the materials she used. The museum also has six finished baskets by her in different styles, like a sieve and a cow-nose basket. Her work can also be found in private collections.

Later Life and Legacy

Christine Navarro Paul's husband, Chief Benjamin Paul, died in 1934. She continued to support her tribe by weaving baskets. She also kept teaching younger generations how to weave until she passed away in 1946. Her work helped keep the Chitimacha basket-making tradition alive.

Images for kids

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |