American Indian boarding schools facts for kids

American Indian boarding schools, also also known as American Indian Residential Schools, were schools set up in the United States. They existed from the mid-1600s to the early 1900s. Their main goal was to make Native American children and young people live like European Americans. This was often called "civilizing" or "assimilating" them.

These schools tried to erase Native American cultures. Children were often forced to give up their languages and religions. At the same time, the schools taught them basic Western education. Christian missionaries first started these schools. The government often allowed missionaries to open schools on reservations.

Later, the government also started its own schools. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) opened many off-reservation boarding schools. These schools aimed to blend Native children into American society. They often brought children from many different tribes together.

Life at these schools was usually very strict. Children were made to cut their hair and wear American-style uniforms. They were not allowed to speak their native languages. Their tribal names were often changed to English names. This was all part of the plan to make them "American" and "Christian."

It was especially hard for younger children. They were taken away from their families and told to forget their Native American identities. Sadly, some children got sick and died in these schools. Later investigations found cases of harsh treatment and mistreatment, especially in church-run schools.

Despite these challenges, Native people found ways to keep their cultures alive. As Dr. Julie Davis explained, these schools were places of both loss and strength. They helped shape new Native American identities. They also encouraged the fight for Native self-determination later on.

Since those times, Native American tribes have worked hard for their rights. They have gained laws and policies that let them decide how to educate their children. They can now use federal money for education and open their own community schools. Many tribes have also started their own tribal colleges and universities. By 2007, most boarding schools had closed. The number of Native American children in boarding schools dropped to 9,500.

Even today, investigations are ongoing to find more information about Indigenous children who died at these schools.

Contents

- History of Native American Education

- Early Mission Schools

- Nationhood, Indian Wars, and Western Settlement

- Day Schools for Assimilation

- Carlisle Indian Industrial School

- Federally Supported Boarding Schools

- Laws and Policies

- Disease and Death

- Impact of Assimilation

- Schools in the Mid-20th Century and Later Changes

- 21st Century

- Books about Native American Boarding Schools

- Movies and Documentaries about Native American Boarding Schools

- See Also

- Images for kids

History of Native American Education

In the late 1700s, leaders like President George Washington and Henry Knox wanted to "civilize" Native Americans. They believed this would help Native people survive as more European-American settlers moved west. The Civilization Fund Act of 1819 helped this idea. It gave money to groups, mostly religious missionaries, to educate Native American children. These schools were often in or near Native communities.

President Thomas Jefferson also encouraged Native Americans to adopt farming. He believed it would help them support their families better than hunting. He offered help to tribes like the Choctaw Nation to learn these new ways.

Early Mission Schools

In 1634, a Jesuit priest named Fr. Andrew White started a mission in Maryland. He wanted to teach Native Americans about European ways and Christianity. By 1640, Native American children were sent to St. Mary's for education. This included the daughter of the Pascatoe chief.

In 1677, a school for "humanities" opened in Maryland. It was run by two priests. Native youth studied hard and made good progress. Some even went to study in Europe. This showed that Native students were just as smart as European students.

In the mid-1600s, Harvard College in Massachusetts had an "Indian College." It was supported by a church group. In 1665, Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, a Wampanoag man, became the first Native American to graduate from Harvard.

Other early Indian schools were set up in New England. For example, a school in Hanover, New Hampshire, started in 1769. This school later became Dartmouth College, which still supports Native American programs. Missionaries from different churches started these first schools. They believed they could spread education and Christianity to Native Americans.

In the early 1800s, the Foreign Mission School opened in Connecticut in 1816. It was for male students from many non-Christian groups. This included Native American students from tribes like the Cherokee and Choctaw. The school aimed to train young people to help their communities.

Nationhood, Indian Wars, and Western Settlement

Throughout the 1800s, European Americans continued to move onto Native lands. From the 1830s, tribes were forced to move west of the Mississippi River to Indian Territory. As part of land agreements, the U.S. government was supposed to provide education to tribes on their new reservations. Some religious groups set up missions in Kansas and Oklahoma. Some tribes, like the Choctaw, even started their own schools.

After the Civil War and many Indian Wars in the West, more tribes were forced onto reservations. The government increased its efforts to educate Native Americans. They believed assimilation was necessary for tribal people to survive in a changing American society.

Missionaries opened more boarding schools in the West. Because of the large distances, some children had to go to schools far from their homes. At first, President Ulysses S. Grant allowed only one religious group per reservation. But different churches soon pushed to open their own missions.

Day Schools for Assimilation

Day schools were also created to follow federal rules. They were cheaper than boarding schools. Parents also often preferred them because their children could stay closer to home.

For example, the Fallon Indian Day School opened in 1908 on the Stillwater Indian Reservation. Even when boarding schools started closing, many day schools stayed open.

Carlisle Indian Industrial School

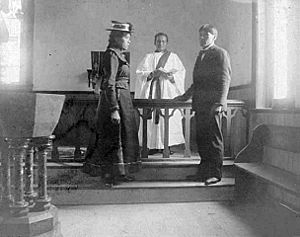

After the Indian Wars, Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt was put in charge of Native prisoners of war in Florida. He started to educate them in European-American culture. He made them cut their hair and wear uniforms. But he also gave them some freedom to govern themselves. Pratt believed in the idea, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." This meant he wanted to erase Native culture to "save" the person by making them American.

Some of the younger men from the prison went to Hampton Institute. This was a college for freed slaves. In 1875, Hampton started a program for Native American students.

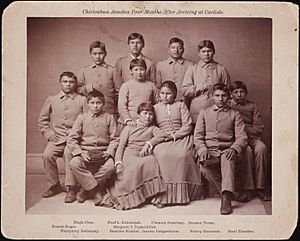

Pratt continued his assimilation ideas at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. He thought Native children could become part of Euro-American culture in one generation. He convinced the government to fund a school far from Native homes. The Carlisle Indian School opened in 1879. It was the first off-reservation school and became a model for over 300 similar schools across the U.S.

Carlisle's lessons focused on rural American life. Boys learned job skills, and girls learned home skills. Students did chores to help the school run itself. They also sold goods at the market. Carlisle had a newspaper, a choir, an orchestra, and sports teams. In the summer, students often lived with local families. This helped them fit into American society and provided cheap labor for the families.

Federally Supported Boarding Schools

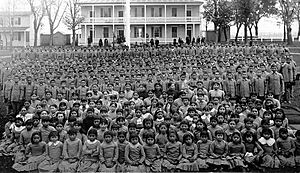

Carlisle's lessons became the model for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. By 1902, the BIA funded 25 off-reservation schools. These schools had over 6,000 students. Federal laws said Native American children had to be educated in American ways. Parents had to agree to send their children. If they refused, officials sometimes used force to get enough students.

Boarding schools were also set up on reservations. These were often run by religious groups. Because of the distances, Native American children were often separated from their families and tribes. At its peak, the BIA supported 350 boarding schools.

When students arrived at these schools, their lives changed a lot. Their hair was cut short, which was a source of shame for many boys. They had to wear uniforms and take English names. They were not allowed to speak their own languages, even to each other. They had to go to church and were often baptized as Christians. Discipline was very strict. Punishments included extra chores, being alone, and physical beatings.

Anna Moore, a former student, remembered the Phoenix Indian School: "If we were not finished [scrubbing the dining room floors] when the 8 a.m. whistle sounded, the dining room matron would go around strapping us while we were still on our hands and knees."

Laws and Policies

In 1776, the government started allowing ministers to teach Native Americans. This grew after the War of 1812. In 1819, Congress gave $10,000 to hire teachers and run schools. This money mostly went to missionary schools, as the government had no other way to educate Native people.

In 1887, Congress passed the Compulsory Indian Education Act. This law provided money for more boarding schools. In 1891, a law allowed federal officers to forcibly take Native American children from their homes. The government believed they were "saving" these children from poverty and teaching them "life skills."

Tabatha Toney Booth wrote that many parents had no choice. Congress allowed officials to stop giving food and clothes to families who refused to send their children. Some agents even used police to kidnap children. But Native police sometimes quit in disgust. Parents also taught their kids to hide. In 1895, nineteen Hopi men were sent to Alcatraz prison because they refused to send their children to school.

Between 1778 and 1871, the U.S. government signed 389 treaties with Native American tribes. Most of these treaties promised education and other services in exchange for land. For example, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 said that education was needed to "civilize" Indians. It pledged to make children aged six to sixteen attend school.

In 1867, a report said that different languages were a big problem. It pushed for Native languages to be replaced with English. This caused arguments because missionaries had been teaching in both languages. In 1870, President Grant started a new policy to get rid of Native languages.

In 1871, the U.S. government stopped signing treaties with Native nations. It also passed a law requiring day schools on reservations. However, in 1873, a report said day schools were not good enough. It argued that children spent too much time at home speaking their native language. This led to more support for boarding schools.

The boarding school movement grew after the Civil War. Reformers believed that education would help Native people become like other citizens. The Carlisle Indian School, founded in 1879, was a key example. Its leader, General Pratt, also used the "outing system." This placed Native students in non-Native homes during summers and after high school. They learned non-Native culture and worked for families. Pratt believed this helped them become Americans.

By the late 1800s, the government wanted to completely assimilate Native Americans into American society. In 1918, the Carlisle boarding school closed. Its methods were seen as old-fashioned. That same year, a new law said that children who were less than 1/4 Native American and had citizen parents should not get separate education if public schools were available.

Meriam Report of 1928

In 1926, the Department of the Interior asked for a study of Native American conditions. The Meriam Report, published in 1928, suggested changes for Native American education:

- Stop teaching only European-American values.

- Educate younger children in community schools near home. Older children could go to non-reservation schools for higher grades.

- The Indian Service (now BIA) should teach Native Americans skills for both their own communities and U.S. society.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 was a big change. It ended the period of dividing up Native lands. It also supported Native self-government. This law encouraged Native Americans to attend vocational schools and colleges. It also promoted community day schools and public school attendance for Native children. The Johnson-O'Malley Act (JOM) in the same year helped states pay for Native students in public schools. This aimed to reduce the number of children in boarding schools.

The Termination Period

In 1953, Congress started a new policy called "termination." Senator Arthur Watkins said the goal was to end Native Americans' status as "wards of the government." This policy aimed to move Native people to cities and end tribes as separate groups. Sixty-one tribes were "terminated" during this time.

1968 Onward

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson ended the termination policy. He also told the Secretary of the Interior to create Indian School boards. These boards would be made up of community members.

Major laws to improve Indian education came in the 1970s. The Indian Education Act of 1972 recognized the special needs of Native American students. The most important law was the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This law gave tribes the power to manage their own education programs. It also allowed them to create community schools on their reservations.

In 1978, Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act. This law gave Native American parents the legal right to refuse their child's placement in a boarding school. This act was passed after hearing about the abuses in Indian boarding schools.

Because of these changes, many large Indian boarding schools closed in the 1980s and early 1990s. Some on reservations were taken over by tribes. By 2007, about 9,500 Native American children were in boarding schools. This included those in 45 on-reservation schools, seven off-reservation schools, and 14 dorms. It's thought that hundreds of thousands of Native Americans attended these schools over the years.

Today, about two dozen off-reservation boarding schools still operate. However, their funding has decreased.

Disease and Death

In the early 1900s, boarding schools often had poor sanitation and crowded conditions. Students were at high risk for diseases like tuberculosis, measles, and trachoma. There were no antibiotics or vaccines then, so epidemics spread quickly.

Overcrowding made diseases spread fast. Staff were often underpaid and medical care was not regular. School officials sometimes failed to separate sick children from healthy ones. Tuberculosis was especially deadly. Many children died while at these schools. Often, students could not talk to their families. Parents were not told when their children got sick or died. Many Native American deaths during the 1918–19 influenza pandemic happened in boarding schools.

The 1928 Meriam Report said that diseases were common because of poor food, overcrowding, bad sanitation, and students being overworked. The report stated that death rates for Native American students were much higher than for other groups. A report about the Phoenix Indian School said that in 1899, a measles outbreak led to 325 cases of measles, 60 cases of pneumonia, and 9 deaths in just 10 days.

Impact of Assimilation

From 1810 to 1917, the U.S. government helped pay for mission and boarding schools. By 1885, 106 Indian Schools had been set up. Many were on old military bases. These schools were seen as a way to make Native Americans part of mainstream American culture. This meant taking children from their families, making them Christian, stopping them from practicing their culture, and making them live in a strict, military-like way.

When students arrived, the routine was usually the same. First, they had to give up their tribal clothes and get their hair cut. Second, the school day was organized like a military camp. Every part of student life followed a strict schedule.

One student remembered a mealtime routine in the 1890s: A small bell rang, and students pulled out chairs. The student sat down, but everyone else stayed standing. A second bell rang, and everyone sat. A man spoke at one end of the hall, but everyone looked at their plates. A third bell rang, and everyone started eating. The student was so scared they cried instead.

Besides mealtime, students were taught to farm using European methods. Schools often had farms to grow their own food and raise animals.

From the moment students arrived, they were not allowed to "be Indian." School leaders banned tribal singing, dancing, traditional clothes, native religions, and speaking tribal languages. They also tried to change traditional gender roles. They told girls that their grandmothers' ways were old-fashioned.

Moving Native Americans to reservations and the Dawes Act of 1887 took away nearly 50 million acres of Native land. On-reservation schools were either taken over by non-Native leaders or destroyed. Native-controlled schools almost disappeared.

Schools used verbal correction and physical punishment. Students had their mouths washed out with lye soap for speaking their native languages. They could be locked up with only bread and water. They faced beatings and other harsh discipline daily.

Girls were especially targeted. The government wanted to train them to be "good housewives." They hoped these women would help their future families fit into American culture.

Historian Brenda Child says that boarding schools helped Native people from different tribes connect. Students from different languages and cultures lived and worked together. They formed strong friendships and shared their cultures. Many graduates married classmates, worked for the Indian Service, or returned to their reservations and became tribal leaders. These schools created new friendships and political alliances.

Jacqueline Emery says that writings from boarding school students show their strength. Even though school leaders censored their writings, they show how students resisted the school rules. Some students, like Gertrude Bonnin and Francis La Flesche, became educated and were early Native activists.

After leaving boarding schools, students were expected to return to their tribes and encourage assimilation. But many felt lost. They faced language and cultural barriers. They also suffered from trauma from the abuse they experienced. They struggled to respect elders and faced resistance when trying to bring American changes to their families.

Despite the hardships, Native students built a foundation of resistance. They used what they learned to speak up and become activists. They were smart and resourceful. Many parents resisted their children being taken. They hid their kids or encouraged them to run away. This was a form of resistance.

The Ojibwe people in Minnesota showed armed resistance in 1900. They stood as armed guards around construction workers building a government school. This showed the workers they were not welcome. This type of armed resistance was common in many Native communities.

A common resistance tactic was speaking their native language. Schools tried to stop this, but speaking their language kept their culture alive. It often led to physical abuse, but students continued to do it to show their roots were strong. Another form of resistance was misbehaving. Students would break rules, act out, or start fires or fights. They hoped to be kicked out and sent home. These acts of courage helped slow down the forced Americanization.

The effects of these schools still impact Native communities today. Mary Annette Pember, whose mother attended a boarding school, recalled her mother's stories of "beatings, shaming, and the withholding of food." The trauma from these schools continues for generations.

When school staff visited former students, they judged their success. They looked for "orderly households," "Christian weddings," and children in school. General Richard Henry Pratt believed that to keep Native Americans "civilized," they needed to stay in American society.

Schools in the Mid-20th Century and Later Changes

Attendance in Indian boarding schools grew until the 1960s. In 1969, the BIA ran 226 schools in 17 states. This included 77 boarding schools with over 34,000 children. Many more attended BIA day schools or public schools with BIA support.

Enrollment was highest in the 1970s, with an estimated 60,000 Native American children in boarding schools in 1973.

Growing Native American activism and studies like the Kennedy Report of 1969 led to the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This law allowed tribes to manage their own education programs. It also let them create community schools on their reservations.

In 1978, the Indian Child Welfare Act was passed. This law gave Native American parents the legal right to refuse their child's placement in a school. This was a direct result of the evidence of abuse in boarding schools.

Because of these changes, many large Indian boarding schools closed in the 1980s and early 1990s. Some on reservations were taken over by tribes. By 2007, the number of Native American children in boarding school dorms dropped to 9,500. This includes those in 45 on-reservation schools, seven off-reservation schools, and 14 dorms.

21st Century

Around 2020, the Bureau of Indian Education runs about 183 schools. Most are not boarding schools and are on reservations. These schools have 46,000 students. Today, people focus on the quality of education and meeting federal standards. In 2020, the BIA created new rules to help prepare students for college and careers.

Books about Native American Boarding Schools

- Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928, by David Wallace Adams (1995)

- Indian Horse, by Richard Wagamese (Ojibwe) (2012)

Movies and Documentaries about Native American Boarding Schools

- Our Spirits Don't Speak English: Indian Boarding School, Documentary (2008)

- The Only Good Indian, 2009 film

- Our Fires Still Burn, Documentary (2013)

- Unspoken: America's Native American Boarding Schools, Documentary (2016)

- Indian Horse, based on the book by Richard Wagamese, film (2017)

See Also

- List of Native American boarding schools

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |