Wampanoag facts for kids

| Wôpanâak | |

|---|---|

Cheryl Andrews-Maltais (right), Chairperson of the Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah

|

|

| Total population | |

| 2,756 (2010 census), 3,841 (2023) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Massachusetts, formerly Rhode Island | |

| Languages | |

| English, historically Wôpanâak | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Massachusett, Agawam, Nauset Naumkeag, and other Algonquian peoples |

The Wampanoag (pronounced WAHM-pah-nawg), also known as Wôpanâak, are a Native American people from the Northeastern Woodlands. Today, most Wampanoag live in southeastern Massachusetts. Long ago, their lands also included parts of eastern Rhode Island and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket.

Before Europeans arrived in the 1600s, about 40,000 Wampanoag people lived in 67 villages. They had lived on this land for over 12,000 years. A serious illness, likely spread by rats from European ships between 1615 and 1619, greatly reduced their population. This made it easier for European colonists to settle in the area.

Later, in 1675, Wampanoag Chief Metacom (also known as King Philip) led an important war against the colonists. Many Wampanoag lost their lives in this conflict, and some were forced into difficult labor far from their homes.

Today, the Wampanoag people continue to live in their ancestral lands. They keep their culture alive through oral traditions, ceremonies, songs, dances, and social gatherings. Hunting and fishing are still important parts of their traditional way of life. Two Wampanoag tribes are officially recognized by the United States government: the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah).

Contents

- The Name Wampanoag

- Wampanoag Communities and Lands

- Wampanoag Culture and Daily Life

- Wampanoag Language and Its Revival

- A Look at Wampanoag History

- Sachems of the Wampanoag

- Current Status of Wampanoag Tribes

- Cultural Heritage Groups

- Wampanoag Population Over Time

- Notable Historical Wampanoag People

- Wampanoag in Media

- See also

The Name Wampanoag

The name Wampanoag likely comes from Wapanoos. This word first appeared on a map in 1614. The Wampanoag people translate this word to "People of the First Light."

In early colonial records, one Wampanoag group was called the Pokanoket. Their leaders, like Massasoit and later Metacomet, guided the Wampanoag people when English settlers first arrived in New England. The Pokanoket lived near what is now Warren, Rhode Island and Bristol, Rhode Island.

Wampanoag Communities and Lands

The Wampanoag people lived in many different communities across their traditional lands. Here are some of the main groups and where they lived:

List of Wampanoag Groups

| Group | Area inhabited |

|---|---|

| Assawompsett Nemasket | Lakeville, Middleborough and Taunton, Massachusetts |

| Assonet | Assonet Neck, Assonet-Freetown, Greater New Bedford |

| Gay Head or Aquinnah | Western point of Martha's Vineyard |

| Chappaquiddick | Chappaquiddick Island |

| Nantucket | Nantucket Island |

| Nauset | Cape Cod |

| Mashpee | Cape Cod |

| Patuxet | Eastern Massachusetts, on Plymouth Bay |

| Pokanoket (after Metacomet's rebellion known as "Annawon's People" or the Seaconke Wampanoags) | East Bay of Rhode Island including Warren, Rhode Island, and parts of Seekonk, Massachusetts |

| Pocasset | Fall River, Massachusetts, Tiverton, Rhode Island |

| Herring Pond | Plymouth & Cape Cod |

Wampanoag Culture and Daily Life

The Wampanoag people moved with the seasons. They traveled between different places in southern New England to find food and resources. Men often went on long fishing trips along the coast, sometimes for weeks or months.

Wampanoag women were skilled farmers. They grew important crops like corn, climbing beans, and squash, often called the "three sisters." These crops were a main part of their diet. Men hunted and fished to add to the food supply. Each community had its own territory for hunting, fishing, and farming.

The Wampanoag had a unique family system. Family lines and important roles were passed down through the mother's side. Women owned property, and when a young couple married, they often lived with the wife's family. Women elders had a say in choosing chiefs, called sachems. Men usually handled political matters with other groups and led in times of conflict.

Women were very important in providing food. They were responsible for most of the farming and gathering of wild fruits, nuts, berries, and shellfish. Men focused on hunting and fishing. Women's roles in food production gave them significant influence in their communities.

The Wampanoag were organized into a group of communities led by a head sachem. This leader was chosen by women elders. Sachems had to listen to their own tribal council and other local leaders. They also managed trade and protected their allies. Both men and women could be sachems.

Wampanoag Language and Its Revival

The Wampanoag people originally spoke Wôpanâak. This language is a dialect of the Massachusett language and belongs to the Algonquian languages family.

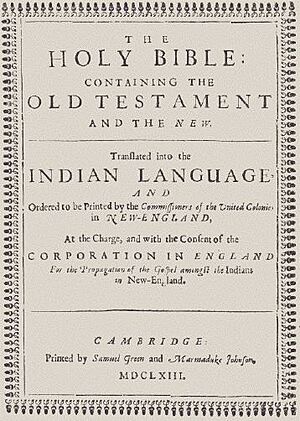

In 1663, the first Bible published in America was translated into the Wampanoag language by a missionary named John Eliot. He created a writing system for the language, and many Wampanoag learned to read and write in Wôpanâak. They used it for letters, important documents, and historical records.

After the American Revolution, fewer and fewer Wampanoag people spoke the language. Many Wampanoag women married people from other language groups, which made it harder to keep the language alive.

In 1993, Jessie Little Doe Baird, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, started the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project. This project has successfully taught some children, making them the first Wôpanâak speakers in over a hundred years! The project is training new teachers and creating school lessons. Jessie Little Doe Baird also created a 10,000-word Wôpanâak-English dictionary. In 2018, Mashpee High School even started offering a course to teach the language.

A Look at Wampanoag History

Early Encounters with Europeans

Wampanoag people first met Europeans in the 1500s. European ships came to the New England coast for trade and fishing. In 1524, Giovanni de Verrazano met Wampanoag and Narragansett tribes in what is now Rhode Island.

Sadly, some Wampanoag were captured and taken far from their homes. For example, in 1614, Captain Thomas Hunt captured several Wampanoag and sold them in Spain. One of these was a Patuxet man named Tisquantum (also known as Squanto). He eventually made his way back home in 1619, only to find that his entire Patuxet tribe had been lost to a terrible illness.

Between 1616 and 1619, a widespread illness, likely leptospirosis spread by rats from European ships, severely affected the Wampanoag and other tribes. This tragic event greatly reduced their population.

The Pilgrims and Early Settlements

In 1620, the Pilgrims arrived in Plymouth. Tisquantum and other Wampanoag people shared their knowledge with the newcomers. They taught the Pilgrims how to grow corn, squash, and beans (the Three Sisters) that thrived in New England. They also showed them how to catch and prepare fish and seafood. This help was crucial for the Pilgrims to survive their first harsh winters. Tisquantum lived with the Pilgrims and helped them communicate with Massasoit, the Wampanoag sachem.

The Wampanoag are often shown in stories about the First Thanksgiving. However, many Native Americans and historians say that the popular story is not entirely accurate. Historical accounts confirm that Native Americans were at the 1621 celebration, but the event was likely different from the romanticized versions often told.

In 1623, Massasoit became very ill, but the colonists helped him recover. Later, in 1632, the Narragansetts attacked Massasoit's village. The colonists helped the Wampanoag push them back.

After 1632, the number of European settlers grew rapidly. The Plymouth Colony expanded, and other settlements like the Puritan ones around Boston became very large. In 1638, the colonists defeated the powerful Pequot Confederation. By 1643, the Mohegans, with colonial support, became the strongest tribe in southern New England.

Adopting Christianity

After 1650, missionaries like John Eliot tried to teach local tribes about Christianity. Those who chose to convert often moved to special settlements called "Praying towns." Missionaries hoped that Native Americans would adopt new ways of life, including farming and new laws. After many difficult times, some Wampanoag chose to adopt Christianity.

In some places, like on Martha's Vineyard, Wampanoag people who converted often blended their traditional ways with Christian practices. They might keep their traditional clothing and hairstyles, and continue their cultural ceremonies.

Metacomet, also known as King Philip

Massasoit, a Wampanoag leader, adopted some colonial customs. Near the end of his life, he asked the Plymouth leaders to give his two sons English names. His older son, Wamsutta, was named Alexander, and his younger son, Metacom, was named Philip.

After Massasoit passed away, Alexander became the Wampanoag sachem. He became ill after a meeting with the colonists and died shortly after. Many Wampanoag believed he had been poisoned. The next year, his brother Philip (Metacom) became the new sachem.

Under Philip's leadership, the relationship between the Wampanoag and the colonists changed. Philip worried that the growing number of colonists would take over all their land and change their way of life. He decided to stop the expansion of colonial settlements. At this time, the colonial population in southern New England was much larger than the Native American population. Philip began to visit other tribes to form alliances against the colonists.

In 1671, Philip was asked to meet in Taunton, Massachusetts. He signed an agreement that required the Wampanoag to give up their firearms. However, his men never delivered their weapons.

Philip slowly gained allies, including the Nipmuck, Pocomtuc, and Narragansett tribes. They planned an uprising for the spring of 1676. But in March 1675, John Sassamon was killed. Sassamon was a Christian Native American who had worked as an interpreter and advisor to Philip. A week before his death, Sassamon had told the Plymouth governor that Philip was planning a war.

Sassamon was found dead a week later. Three Wampanoag men were accused of the murder and later executed by the colonists in June 1675. This event, along with rumors that the colonists wanted to capture Philip, sparked the war. Philip called a council, and most Wampanoag decided to follow him.

King Philip's War

On June 20, 1675, some Wampanoag attacked colonists in Swansea, Massachusetts, and surrounded the town. Five days later, they destroyed it. This marked the beginning of King Philip's War. The allied tribes in southern New England attacked many colonial settlements.

At first, many Native Americans offered to help the colonists fight against King Philip. However, the colonists' mistrust led them to stop accepting this help. The Massachusetts government moved many Christian Native Americans to Deer Island in Boston Harbor. This was to protect them from angry settlers and also to prevent any rebellion.

The war spread across New England. The Narragansetts of Rhode Island joined the fight after colonists attacked one of their villages. This battle, known as the "Great Swamp Massacre," resulted in many Narragansett lives lost.

The war began to turn against Philip in the spring of 1676. Colonial troops captured Canonchet, a Narragansett leader, and he was executed.

During the summer, Philip tried to escape his pursuers. Colonial forces attacked his hideout in August, and many Wampanoag were captured or lost their lives. Philip's wife and young son were captured and sent far away to work in difficult conditions. On August 12, 1676, colonial forces found Philip's camp, and he was killed.

After the War

After the death of Metacomet and many other leaders, the Wampanoag population was greatly reduced. Only about 400 Wampanoag survived the war. Many Narragansetts and Nipmucks also suffered heavy losses. Many Wampanoag were forced into difficult labor. Men were often sent to places like the West Indies or Bermuda. Women and children were sometimes used as servants in New England. The remaining Wampanoag were resettled in a few of the original Praying towns. Overall, the war caused immense loss of life for both Native Americans and colonists.

The 1700s to 1900s

Mashpee Community

The Wampanoag groups on the coastal islands were an exception, as they had remained neutral during the war. Mainland Wampanoag were often forced to resettle with other groups in Praying towns in Barnstable County. Mashpee became the largest Indian reservation in Massachusetts, located on Cape Cod. In 1660, colonists set aside about 50 square miles (130 km²) for Native Americans there. By 1665, they had some self-government, using an English-style court system. Leaders declared that this land could not be sold to non-Mashpee people without everyone's agreement.

After the American Revolutionary War, in 1788, the state removed the Wampanoag's ability to self-govern. A committee of five European-American members was appointed to oversee them. In 1834, the state gave back some self-government, but the Mashpee people were still not fully independent. To encourage them to adopt colonial ways, the state divided some of their communal land into smaller plots for individual households in 1842. Over time, much of their land was lost to others.

Wampanoag on Martha's Vineyard

On Martha's Vineyard in the 1700s and 1800s, there were three reservations: Chappaquiddick, Christiantown, and Gay Head. The Chappaquiddick Reservation was on a small island. After some land sales, the remaining land was divided among the Native American residents in 1810. Many residents later moved to nearby Edgartown to find work and gain more rights.

Christiantown was originally a Praying town on the northwest side of Martha's Vineyard. By 1849, most of its land had been divided among residents. The land was not very fertile, so many tribal members left to find jobs in cities. Wampanoag oral history says that Christiantown was devastated by a smallpox epidemic in 1888.

The third reservation on Martha's Vineyard was created in 1711 for the Gay Head (now Aquinnah) Native Americans. This land was on a peninsula, which helped the Wampanoag maintain their isolation. By 1849, they had 2,400 acres (9.7 km²), with some distributed and some kept as communal property. Unlike other groups, they managed their own affairs and did not allow non-Native Americans to settle on their land. They had strict rules about who could be a tribal member, which helped them keep their tribal identity strong.

The Wampanoag on Nantucket Island were almost completely lost to an unknown illness in 1763. The last Nantucket Wampanoag person passed away in 1855.

Sachems of the Wampanoag

| Indigene Name | Name of Colonizators | Time of Reign | Affinity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wasamegin | Massasoit | before 1621–1662 | Brother 'Quadequina' as Co-Sachem | |

| Wamsutta | Alexander Pokanoket | 1662 | Son of the Predecessor | |

| Metacomet | Philip Pokanoket | 1662–1676 | Brother of the Predecessor |

Current Status of Wampanoag Tribes

Today, there are two federally recognized Wampanoag tribes and one state-recognized Wampanoag tribe. The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe has about 3,200 enrolled citizens in 2023. The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) had 1,364 enrolled tribal citizens in 2019. The state-recognized Herring Pond Tribe has not publicly posted their citizen records.

A project called "Massachusetts Native Peoples and the Social Contract: A Reassessment for Our Times" began in 2015. It aims to provide an updated report on the culture, language, and economy of Wampanoag peoples, including those from both federally and non-federally recognized tribes.

Federally Recognized Wampanoag Tribes

Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe has over 1,400 enrolled members. To be a member, individuals must meet specific requirements, including family lineage and community involvement. Since 1924, they have held an annual powwow in early July in Mashpee.

The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Council was formed in 1972. In 1974, the Council asked the Bureau of Indian Affairs for official recognition. After many years, the Mashpee Wampanoag received provisional recognition in April 2006 and official federal recognition in February 2007.

The Mashpee Wampanoag tribal offices are located in Mashpee on Cape Cod. The tribe is working on plans for a casino, but there are rules and challenges they need to overcome.

A December 2021 ruling from the United States Department of the Interior gave the Mashpee Wampanoag "substantial control" over 320 acres (1.3 km²) on Cape Cod. This decision helped secure their land for the future.

Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)

The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) is based in Aquinnah, Massachusetts. The name Aquinnah means "land under the hill." They are the only Wampanoag tribe with a formal land-in-trust reservation, located on Martha's Vineyard. Their reservation covers 485 acres (1.96 km²) on the southwestern part of the island.

In 1972, Aquinnah Wampanoag descendants created the Wampanoag Tribal Council of Gay Head, Inc., to work towards self-determination and federal recognition. The Bureau of Indian Affairs officially recognized the tribe in 1987. The tribe has 1,121 enrolled citizens.

Gladys Widdiss, an Aquinnah Wampanoag tribal historian, served as the President of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head from 1978 to 1987. During her time as president, the Aquinnah Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head gained federal recognition. They also acquired important lands like Herring Creek, the Gay Head Cliffs, and the cranberry bogs around Aquinnah.

The Aquinnah Wampanoag are currently led by tribal council chair Cheryl Andrews-Maltais, who was elected in November 2007.

State-Recognized Tribe

The Herring Pond Wampanoag Tribe is a state-recognized tribe based in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey granted them state-recognition on November 19, 2024, through Executive Order 637.

Cultural Heritage Groups

Many groups identify as Wampanoag and work to preserve their cultural heritage. The Massachusetts' Commission on Indian Affairs works with some of these organizations.

Some groups have expressed interest in seeking federal recognition, but none have actively petitioned for it yet. These groups include:

- Assawompsett-Nemasket Band of Wampanoags

- Assonet Band of Wampanoags

- Chappaquiddick Wampanoag Tribe, South Yarmouth, MA

- Massachuset-Ponkapoag Tribal Council, Holliston, MA

- Nova Scotia Wampanoag Council, Clark's Harbour, NS

- Pocasset Wampanoag Indian Tribe, Great Falls, MA

- Seaconke Wampanoag Tribe, Warwick, RI

Wampanoag Population Over Time

| Year | Number | Note | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1610 | 6,600 | mainland 3,600; islands 3,000 | James Mooney |

| 1620 | 5,000 | mainland 2,000 (after the epidemics); islands 3,000 | unknown |

| 1677 | 400 | mainland (after King Philip's War) | general estimate |

| 2000 | 2,336 | Wampanoag | US Census |

| 2010 | 2,756 | Wampanoag | US Census |

Notable Historical Wampanoag People

- Askamaboo, a female sachem from Nantucket in the 1600s

- Crispus Attucks, the first person killed in the Boston Massacre

- Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, the first American Indian to graduate from Harvard College

- Corbitant, a 17th-century sachem of the Pocasset

- Massasoit, the sachem who became friends with the Mayflower Pilgrims

- Metacom or Metacomet, Massasoit's second son, also called Philip, who led King Philip's War (1675–1676)

- John Sassamon, an early translator

- Wamsutta, Massasoit's oldest son, also known as Alexander

- Weetamoo of the Pocasset, a woman who supported Metacom

Wampanoag in Media

- Tashtego was a fictional Wampanoag harpooneer from Gay Head in Herman Melville's novel Moby Dick.

- Wampanoag history from 1621 to King Philip's War is shown in the first part of We Shall Remain, a 2009 documentary.

See also

In Spanish: Wampanoag para niños

In Spanish: Wampanoag para niños

- The City of Columbus was an 1884 shipwreck where a group of Wampanoag risked their lives to save passengers

- Briggs Report (1849)

- Cuttyhunk

- Earle Report

- Federally recognized tribes

- List of early settlers of Rhode Island

- Native American tribes in Massachusetts

- Old Indian Meeting House, 1684 church

- State recognized tribes in the United States

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |