Chiricahua facts for kids

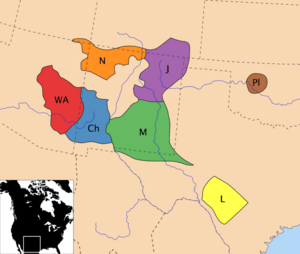

Location of Apache tribes in the late 18th century (Ch – Chiricahua, WA – Western Apache, M – Mescalero, J – Jicarilla, L – Lipan, Pl – Plains Apache, N – Navajo, a separate people speaking a related language)

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 650 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

( |

|

| Fort Sill | 712 |

| New Mexico | 149 |

| Languages | |

| English, Chiricahua Apache language | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Native American Church, traditional tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Plains Apache, Jicarilla Apache, Lipan Apache, Mescalero Apache, Western Apache, Navajo | |

The Chiricahua (pronounced CHIRR-i-KAH-wuh) are a group of Apache Native Americans. They lived in the Southern Plains and Southwestern United States.

The Chiricahua are related to other Apache groups like the Ndendahe, Tchihende, Sehende (Mescalero), Lipan, Salinero, Plains, and Western Apache. Historically, they shared a common area, language, and customs. They also had family ties with other Apaches. When Europeans first arrived, the Chiricahua lived on a huge territory of about 15 million acres. This land was in what is now Southwestern New Mexico, Southeastern Arizona in the United States, and Northern Sonora and Chihuahua in Mexico.

Today, Chiricahua people are part of three federally recognized tribes in the United States. These are the Fort Sill Apache Tribe near Apache, Oklahoma, the Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Reservation near Ruidoso, New Mexico, and the San Carlos Apache Tribe in southeastern Arizona.

Contents

What Does "Chiricahua" Mean?

The name Chiricahua was given to this Apache group by the Spanish. It was also spelled in different ways like Chiricagui or Chiricagua. Other Apache groups had their own names for the Chiricahua. For example, the White Mountain Coyotero Apache called them Ha'i’ą́há. The San Carlos Apache called them Hák'ą́yé, which means "Eastern Sunrise" or "People in the East."

The Chiricahua people called themselves Nde, Ne, Néndé, Héndé, Hen-de, or õne. All these words mean "The People" or "Men." They never called themselves "Apaches." They used different words for outsiders like Americans or Mexicans. For example, they called Americans Daadatlijende, meaning "Blue/green eye people." Or they used Indaaɫigáí, meaning "White skinned people."

Chiricahua Culture and Groups

The Chiricahua were not one single group but several smaller bands that were connected. These included the Chokonen, Chihenne, Nednai, and Bedonkohe. Today, they are all called Chiricahua. However, they were more accurately known as "Central Apaches."

These Apachean groups and the Navajo came from Asia, crossing the Bering Strait from Siberia. As they moved south, different groups formed with their own languages and cultures. Some experts believe that the Lipan Apache and the Navajo were pushed south by other Great Plains tribes like the Comanche and Kiowa. The different Apache groups and the Navajo became culturally distinct, even though they spoke similar languages.

A Look at Chiricahua History

Many famous chiefs led the Chiricahua and related Apache groups. The Tsokanende (Chiricahua) were led by chiefs like Cochise. After Cochise, his sons Tahzay and Naiche led the group. Other important chiefs included Chihuahua, Ulzana, and Pionsenay.

The Tchihende (Mimbreño) people had leaders like Mangas Coloradas, Cuchillo Negro, Nana, and Victorio. The Ndendahe (Mogollón and Carrizaleño) Apache people were led by chiefs like Juh and Goyaałé (known as Geronimo). After Victorio's death, Nana, Geronimo, Mangus (Mangas Coloradas' son), and Naiche were the last leaders of the Central Apaches. They were the last to fight against the U.S. government in the American Southwest.

Early Relations with Europeans

From the start, there was conflict between Europeans and Apaches. They fought over land and resources. Spanish and Mexican settlers had already been on Apache lands for over 100 years. When United States settlers arrived, they also competed for land. After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the U.S. promised to stop Apache raids into Mexico.

At first, the Apache were unsure about the U.S. colonists. Sometimes, they even joined with them against the Mexicans. In 1852, the U.S. and some Chiricahua signed a treaty, but it didn't last long. In the 1850s, American miners and settlers moved into Chiricahua territory. This caused problems and forced the Apache to change their nomadic way of life.

The U.S. Army defeated the Apache and forced them onto reservations. These lands were often not good for farming, which the U.S. wanted them to do. Today, the Chiricahua work to preserve their culture. They are a living and important part of American culture, while still keeping their unique history.

Growing Conflicts and Wars

Before 1860, the Chiricahua lived mostly peacefully with Americans in the New Mexico Territory. However, several events led to more conflict.

In 1837, the chief of the Warm Springs Mimbreños, Soldado Fiero, was killed by Mexican soldiers. His son, Cuchillo Negro, then fought against Chihuahua for revenge. In the same year, an American named John Johnson invited the Coppermine Mimbreños to trade. When they gathered, Johnson and his men opened fire, killing about 20 Apache, including Chief Juan José Compá. Mangas Coloradas saw this attack. This made him and other Apache warriors want revenge for many years.

After the U.S./Mexican War (1848) and the Gadsden Purchase (1853), more Americans came into the territory. This led to more problems. At first, the Apache, including Mangas Coloradas and Cuchillo Negro, were not hostile to Americans. They saw them as enemies of their Mexican enemies.

In 1857, U.S. Army campaigns killed Cuchillo Negro and other Apaches. In December 1860, miners caused trouble in the Pinos Altos area. Mangas Coloradas went to talk to them, asking them to leave. But the miners treated him badly. His followers and other Chiricahua bands were very angry about how their respected chief was treated.

In 1861, the U.S. Army captured and killed some of Cochise's family near Apache Pass. This event became known as the Bascom Affair. In 1863, General James H. Carleton invited Mangas Coloradas to talk about peace. But the chief was arrested and killed by American soldiers. His people were furious. From then on, the Chiricahuas fought almost constantly against U.S. settlers and the Army for the next 23 years. Chiefs like Cochise, Chihuahua, Ulzana, Victorio, Nana, and Juh led these fights.

In 1872, General Oliver O. Howard made peace with Cochise. The U.S. created a Chiricahua Apache Reservation near Fort Bowie, Arizona. It stayed open for about four years until Cochise died. In 1876, the U.S. moved the Chiricahua to the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation. This was because of public anger after some killings. The Apache hated the desert environment of San Carlos. Many left the reservation and sometimes raided nearby settlers.

The last Apache warriors, including Geronimo and Naiche (Cochise's son), surrendered to General Nelson Miles in 1886. They had made a stronghold in the Chiricahua Mountains. General George Crook and General Miles pursued them with the help of Apache scouts. Mexico and the U.S. had an agreement allowing troops to cross the border. This made it impossible for the Chiricahua to escape. Tired and without rest, they finally surrendered.

The last 34 hold-outs, including Geronimo and Naiche, surrendered in September 1886. They were sent by train to Fort Marion, Florida, along with most other Chiricahua. Some, like Massai, escaped and walked 1,200 miles back to Arizona.

After many Chiricahua died at Fort Marion, the survivors were moved to Alabama and then to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Geronimo's surrender marked the end of the Indian Wars in the United States. However, some Chiricahua, known as the "Nameless Ones," were never captured. They escaped to the remote Sierra Madre mountains in Mexico. There, they built hidden camps and continued to live freely.

In August 1912, the U.S. Congress released the surviving Chiricahua prisoners from their prisoner-of-war status. They were offered land at Fort Sill, but faced resistance from local people. They could choose to stay at Fort Sill or move to the Mescalero reservation in New Mexico. Two-thirds chose New Mexico, while 78 stayed in Oklahoma. Their descendants live in these places today. They were not allowed to return to Arizona because of the long history of wars.

Chiricahua Bands and Their Lands

In Chiricahua culture, the "band" was more important than the idea of a "tribe." The Chiricahua did not have one name for themselves as a whole people. The name Chiricahua likely comes from a Spanish word for "mountain of the wild turkey." This refers to the Chiricahua Mountains.

The Chiricahua tribal territory covered parts of southeastern Arizona, southwestern New Mexico, northeastern Sonora, and northwestern Chihuahua. Their land stretched from the Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico to the San Pedro River Valley in Arizona.

According to Morris E. Opler (1941), the Chiricahuas had three main bands:

- Chíhéne or Chííhénee’ ('Red Paint People'): Also known as Eastern Chiricahua or Warm Springs Apache.

- Ch'úk'ánéń or Ch'uuk'anén (‘Ridge of the Mountainside People’): Also known as Central Chiricahua or Cochise Apache.

- Ndé'indaaí or Nédnaa'í ('Enemy People'): Also known as Southern Chiricahua or Bronco Apache.

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe in Oklahoma says they have four bands:

- Chíhéne (Warm Springs and Coppermine Mimbreño bands)

- Chukunen (Chiricahua band)

- Bidánku (Bronco)

- Ndéndai (Nednhi)

Today, they use the word Chidikáágu (from the Spanish word Chiricahua) for the Chiricahua in general. They use Indé for Apache people in general.

Famous Chiricahua Apache People

- Geronimo (1829–1909): A brave warrior and medicine man of the Bedonkohe Ndendahe band.

- Mildred Cleghorn: The first tribal chairperson of the Fort Sill Apache Tribe, elected in 1976.

- Chato (1854–1934)

- Chihuahua (about 1825–1901)

- Cochise: A chief of the Chihuicahui local group of the Tsokanende people.

- Baishan, also known as Cuchillo Negro (about 1796–1857): A war chief of the Warm Springs Tchihende people.

- [[Dahteste|Dahteste (Tahdeste)]: A woman warrior and friend of the famous woman warrior Lozen.

- Delgadito (about 1810–1864): A chief of the Copper Mine Tchihende people.

- Gouyen (about 1857–1903): A woman from the Warm Springs Tchihende group.

- Juh (about 1825–1883): A medicine man and chief of the Janero Nednhi band.

- Lozen (about 1840–1890): A woman warrior and prophet of the Tchihende people.

- Mangas Coloradas (about 1793–1863): A war chief of the Copper Mines Tchihende people.

- Massai (about 1847–1906/1911): A warrior of the Mimbres Tchihende band.

- Naiche (about 1857–1919): Cochise's second son and the last hereditary chief of the Chihuicahui Tsokanende group.

- Nana (about 1805/1810?–1896): A war chief of the Warm Springs Tchihende people.

- Taza (about 1843–1876): Cochise's son and his successor as chief.

- Tso-ay (nicknamed "Peaches"): A scout for General Crook.

- Ulzana (about 1821–1909): A war chief of the Chokonen Tsokanende group.

- Victorio (about 1825–1880): A chief of the Warm Springs Tchihende (Mimbreño) people.

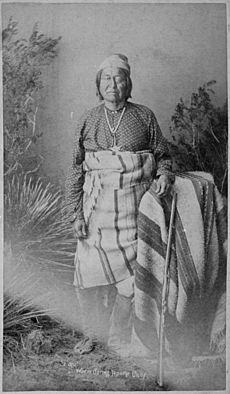

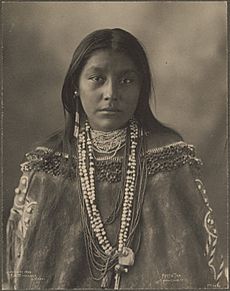

Images for kids

-

Chiricahua National Monument entrance roadway

See also

In Spanish: Chiricahua para niños

In Spanish: Chiricahua para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |