Jicarilla Apache facts for kids

Young Jicarilla Apache boy, 2009

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,755 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Jicarilla | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, traditional tribal religion, Native American Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Southern Athabaskan peoples (Chiricahua Apache, Kiowa Apache, Lipan Apache, Mescalero Apache, Navajo, Tonto Apache, Western Apache) |

The Jicarilla Apache people are part of the larger Apache group. They call themselves Jicarilla Dindéi in their own language. The word Jicarilla comes from Spanish and means "little basket." This name refers to the small, sealed baskets they used for drinking. Other Apache groups knew them as Kinya-Inde, meaning "People who live in fixed houses."

The Jicarilla also called themselves Haisndayin, which means "people who came from below." They believed they were the only ones to come from the underworld, where their first ancestors lived. They believed Hascin, their main god, created the first people, animals, and the sun and moon.

For many years, the Jicarilla Apache lived a peaceful, semi-nomadic life. They moved between the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and the plains of southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. They traveled with the seasons to hunt, gather food, and farm along rivers. They learned farming and pottery from the Puebloan peoples. They also learned how to survive on the plains from other Plains Indians. This gave them a rich and varied diet. Their farming grew so much that they became more settled. They fought less often than other Eastern Apache groups.

Starting in the 1700s, things changed. Pressure from Spanish settlers, other Native American tribes like the Comanche, and later the United States caused them to lose land. They were forced to move from their sacred lands to places not good for living.

The mid-1800s to mid-1900s were very hard. Tribal groups were moved, treaties were broken, and many people died from diseases like tuberculosis. In 1887, they finally got their own reservation. It was made bigger in 1907 to include land better for ranching and farming. Later, they found rich natural resources like oil and gas under their land.

Today, the Jicarilla people no longer live a semi-nomadic life. They are supported by their oil and gas, casino gaming, forestry, ranching, and tourism businesses on the reservation. The Jicarilla are still known for their beautiful pottery, basketry, and beadwork.

Contents

History of the Jicarilla Apache

Early Life and Migrations

The Jicarilla Apaches are part of the Athabaskan language family. They moved from Canada by 1525 CE, or even earlier. They lived in what they saw as their homeland. This land was bordered by four sacred rivers in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. These rivers were the Rio Grande, Pecos River, Arkansas River, and Canadian River. Their land also had sacred mountains. Many Jicarilla also lived along the Cimarron River. By the 1600s, they were found in the Chama Valley, New Mexico, and areas to the east. Before the Spanish arrived, the Jicarilla lived a mostly peaceful life.

Culturally, the Jicarilla were shaped by two groups. The Plains Indians to their east taught them about hunting and warfare. The Puebloan peoples to their west taught them about farming. So, their culture was a mix of moving around to hunt and settling down to farm. After the Spanish came, raiding and warfare became more common. This was partly because they started using horses.

In the 1600s, the Jicarilla were semi-nomadic. They practiced seasonal agriculture which they learned from the Pueblo people and the Spanish. They farmed along the rivers in their territory.

The Apache people are connected to the Dismal River culture of the western Plains. Jicarilla Apache pottery has been found at some of these sites. Some people from the Dismal River culture joined the Kiowa Apache in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Later, due to pressure from the Comanche and Pawnee and French, the Kiowa and other Dismal River people moved south. They then joined the Lipan Apache and Jicarilla Apache nations.

By the 1800s, they were planting many crops along the rivers. This included the upper Arkansas River. They sometimes used irrigation to grow squash, beans, pumpkins, melons, peas, wheat, and corn. They found farming in the mountains safer than on the open plains. They hunted buffalo until the 17th century. After that, they hunted antelope, deer, mountain sheep, elk, and buffalo. Women gathered wild berries, agave, honey, onions, potatoes, nuts, and seeds.

Sacred Land and Beliefs

The Jicarilla have a special creation story. They believe the Creator gave them the land bordered by four sacred rivers. This land had special places to talk with the Creator and spirits. It also had sacred rivers and mountains to respect. There were specific spots to get items for ceremonial rituals. For example, white clay was found near Taos, New Mexico. Red ochre was found north of Taos, and yellow ochre on a mountain near Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico. They believe the "heart of the world" is near Taos.

Traditional Jicarilla stories tell about White Shell Woman, Killer of the Enemies, and Child of the Water. These stories feature places important to them. These include the Rio Grande Gorge, Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico, and the spring near El Prado, New Mexico. Hopewell Lake and especially the Taos Pueblo and the four sacred rivers are also important. The Jicarilla built shrines in places with spiritual meaning. They shared some Taos area sites with the Taos Pueblo.

In 1865, a New Mexican priest named Father Antonio José Martínez noted the Jicarilla's long history. They lived between the mountains and villages. Making pottery was a key way they earned money. The clay for their pottery came from the Taos and Picuris Pueblo areas.

Challenges to Jicarilla Land

As more people moved into the area, and with the idea of Manifest Destiny (the belief that the U.S. should expand across the continent), the Jicarilla's way of life became very difficult. Many people died from hunger, wars, and diseases they had never seen before. They had no natural protection against these new illnesses.

In the early 1700s, the Jicarilla often raided Plains tribes to their east. They used what they gained from these raids to trade with the Pueblo Indians and the Spanish.

When the Comanche people got guns from the French, they teamed up with the Ute. They started pushing other Eastern Apache groups, including the Jicarilla, off the southern plains. As the Jicarilla were pushed out, they moved to the mountains. They also moved closer to the pueblos and Spanish missions. They sought help from the Puebloan peoples and Spanish settlers. For example, in 1724, many Apache groups were destroyed by the Comanches. The Jicarilla had to find safety in the eastern Sangre de Cristo Mountains north of the Taos Pueblo. Some moved to the Pecos Pueblo or joined other Apache groups in Texas. In 1779, a combined force of Jicarilla, Ute, Pueblo, and Spanish soldiers defeated the Comanche. After more fighting, the Comanche finally agreed to peace. This allowed the Jicarilla to return to their old lands in southern Colorado.

Ollero and Llanero Bands

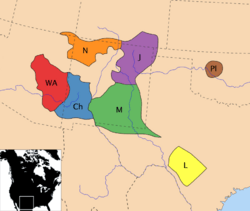

The Jicarilla tribal land has two main types of environments. This helped create two main groups within the tribe: the Llaneros (plains people) and the Olleros (mountain valley people). Every September, these two groups have ceremonial races during Gojiiya. After being pushed off the plains by 1750, the Jicarilla became close friends with the Southern Ute Tribe, who used to be their enemies.

- The Olleros were the mountain people. They were known for making pottery. They lived west of the Rio Grande in New Mexico and Colorado. They settled down as farmers and potters. They sometimes lived in Pueblo-like villages. They earned money by selling pottery made from micaceous clay and basketry. They learned farming from their Pueblo neighbors. "Ollero" is Spanish for "potters." They called themselves Saidindê, meaning "Sand People" or "Mountain Dwellers." The Spanish called them Hoyeros, meaning "mountain-valley people." The Capote Band of Utes became allies with the Olleros. They fought against Southern Plains Tribes like the Comanche and Kiowa. They also traded with Puebloan peoples.

- The Llaneros were the plains people. They lived as nomads in tipis, which they called kozhan. They followed and hunted buffalo on the plains east of the Rio Grande. In winter, they lived in the mountains between the Canadian River and the Rio Grande. They camped and traded near Picuris Pueblo, New Mexico, Pecos, New Mexico, and Taos, New Mexico. They called themselves Gulgahén, meaning "Plains People." The Spanish called them Llaneros, meaning "Plains Dwellers." Their close friends were the Muache Band of Utes. The Jicarilla-Muache fought against the Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Arapaho, and Southern Cheyenne on the Southern Plains.

Battle of Cieneguilla

The Battle of Cieneguilla (pronounced sienna-GEE-ya) was a fight between Jicarilla Apaches, their Ute allies, and the American 1st Cavalry Regiment. It happened on March 30, 1854, near what is now Pilar, New Mexico.

Why the Battle Happened

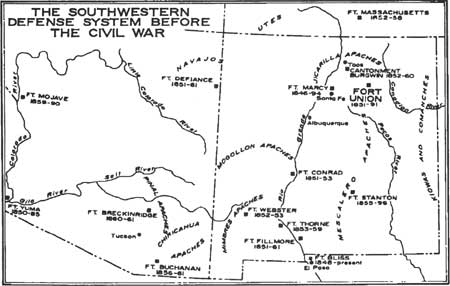

By the mid-1800s, there was a lot of tension. The Spanish, many Native American groups, and American settlers were all claiming land in the southwest. Diseases that Native Americans had no protection against caused many deaths. This made it easier for their lands to be taken. As Native Americans became more upset, they fought harder to protect their lands. By 1850, the Jicarillas were a big threat to travelers on the Santa Fe Trail. The U.S. military built forts to protect travelers. Fort Union was built partly to protect against the Jicarillas. Different cultures not understanding each other also led to fighting.

Leo E. Oliva, who wrote about Fort Union, said that the three groups had different ideas about family, values, religion, land ownership, and warfare.

Fort Union was set up by Colonel Edwin Vose Sumner in 1851. Its job was to protect travelers between Missouri and New Mexico. New Mexico's Governor William Carr Lane tried to make treaties with the Jicarilla. These treaties would move them to reservations where they would farm. They would also get payments for losing their hunting and sacred lands. But the U.S. government stopped the money for this agreement, breaking its promise. To make things worse, all the crops planted by the tribes failed. So, the people kept raiding to survive.

The Battle and What Happened Next

On March 30, 1854, about 250 Apaches and Utes fought 60 U.S. soldiers, called dragoons. The battle was led by Lieutenant John Wynn Davidson. It happened near Pilar, New Mexico. The Jicarilla fought with flintlock rifles and arrows. They killed 22 soldiers and wounded 36. The soldiers had to retreat, losing 22 horses and most of their supplies.

Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke quickly gathered soldiers to chase the Jicarilla. He had help from Pueblo Indian and Mexican scouts, with Kit Carson as a guide. After chasing them through the mountains in winter, Cooke found the Jicarilla. Their leader, Flechas Rayadas, offered peace if they could keep the horses and guns they took. But this offer was not accepted. On April 8, Cooke fought the Jicarilla at their camp. The Jicarilla split into small groups to escape. Many died from the harsh cold weather.

Jicarilla Reservation Established

After the United States expanded westward, the Jicarilla Apache faced many challenges. They became more hostile as people tried to move them. Relations with the Spanish also became bad when Spanish settlers captured and sold Apache people into slavery. After years of war, broken treaties, and being moved, the Jicarilla were the only southwestern tribe without a reservation. In 1873, the two Jicarilla groups, the Llanero and Ollero, united. They sent people to Washington, D.C. to ask for a reservation. Finally, U.S. President Grover Cleveland created the Jicarilla Apache Reservation on February 11, 1887.

Even though they got their reservation, it was sad for the Jicarilla. They knew they would no longer roam their traditional holy lands. Once settled, the Olleros and Llaneros lived in different parts of the reservation. This caused some disagreements that lasted into the 1900s. The Olleros were often seen as "progressives" and the Llaneros as "conservatives."

The land on the reservation was not good for agriculture, except for parts owned by non-tribal members. To survive, they sold timber from the reservation. In 1907, more land was added, making the reservation 742,315 acres. This new land was good for sheep ranching, which became profitable in the 1920s. Before then, many people suffered from malnutrition. In 1914, up to 90% of the tribe had tuberculosis. By the 1920s, it seemed the Jicarilla Apache nation might disappear due to diseases. After some hard times with ranching, many sheep herders moved to the main tribal town of Dulce, New Mexico. For decades, the Jicarilla had few ways to earn money.

After World War II, oil and gas were found on the reservation. This brought in up to $1 million each year. Some of this money was used for a tribal scholarship fund and to build the Stone Lake Lodge. In 1982, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the tribe could charge severance taxes (a tax on natural resources taken from the land) to oil companies drilling on their land.

In 1971, the Jicarilla received $9.15 million as payment for lost tribal lands. This happened after the Indian Claims Commission was created.

Jicarilla Apache Reservation

The Jicarilla Apache Indian Reservation is located in northern New Mexico. It spans two counties: Rio Arriba County and Sandoval County. It stretches from the Colorado border south to Cuba, New Mexico. The reservation is along U.S. Route 64 and N.M. 537.

The reservation covers about 1,364 square miles. In 2000, it had a population of 2,755 people. Most of the people live in the main tribal town of Dulce, New Mexico, which is in the northern part of the reservation.

The southern half of the reservation has open plains. The northern part is in the treed Rocky Mountains. Many mammals and birds cross the reservation during different seasons. These include mountain lions, black bears, elk, Canadian Geese, and turkeys. Rainbow, brown, and cutthroat trout are put into seven lakes on the reservation. However, dry conditions can cause high pH levels in the water. From 1995 to 2000, lake levels were very low due to drought. This caused most of the fish to die during those years. The reservation sits on the San Juan Basin, which has a lot of fossil fuels. This basin is the biggest producer of oil in the Rocky Mountains and the second largest producer of natural gas in the United States.

Jicarilla Apache Culture

The Jicarilla traditionally follow a matrilocal system. This means that when a couple marries, they live near the wife's family. They are organized into matrilineal clans, where family lines are traced through the mother. They have adopted some customs from their Pueblo neighbors. They are famous for their beautiful baskets with unique diamond, cross, or zig-zag patterns. These patterns sometimes show deer, horses, or other animals. They are also known for their beadwork and for keeping Apache fiddle-making alive.

In the 1970s, about 70% of Jicarilla people still followed their traditional religious beliefs.

As of 2000, about 70% of the tribe practices an organized religion, with many being Christians. About half of the tribal members speak Jicarilla, mostly older men and women.

Important ceremonies include:

- The Puberty feast, called "keesta" in Jicarilla. This is a special ceremony for girls or young women.

Annual events include:

- The Little Beaver Celebration in mid-July. This includes a pow-wow, rodeo, draft horse pull, and a five-mile race.

- The Stone Lake Fiesta on September 14 and 15. This event features ceremonial dances, a rodeo, and footraces.

Jicarilla Apache Economy

The Jicarilla Apache Nation's economy is based on several industries:

- Mining: They own and operate oil and gas wells. A 50 MW solar farm is also being built on their land.

- Forestry: They manage timber resources.

- Ranching: They raise cattle and sheep.

- Gaming: They own the Apache Nugget Casino and the Best Western Jicarilla Inn and Casino in Dulce.

- Tourism: They offer tourism activities.

- Retail: They have local businesses.

- Agriculture: They continue some farming.

- Government Jobs: About 50% of tribal members work for the reservation government.

- Traditional Arts: They sell traditional arts like basketry and pottery.

- Media: The tribe also owns and operates radio station KCIE (90.5 FM) in Dulce, NM.

Even with these opportunities, many tribal members face high unemployment and a low standard of living. In 2005, the unemployment rate was 14.2%.

The Jicarilla people live in houses and have a lifestyle similar to other Americans. Food prices at local stores are higher than in bigger U.S. cities. They have access to all modern conveniences and use them based on their wishes and money. High unemployment and low incomes have led to higher crime rates.

Education for Jicarilla Apache Youth

Children on the reservation attend a public school. Before the 1960s, few children finished high school. Since the 1960s, programs from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and scholarships from oil and gas money have helped students. These programs provide chances for higher education. In the 1970s, some tribal members earned graduate degrees. In the 1980s, Apache tribes created offices to help students with their education.

Notable Jicarilla Apache People

- Francisco Chacon, a chief in the 1800s, who led the Jicarilla uprising in 1854.

- Flechas Rayadas, a chief in the 1800s, also involved in the 1854 uprising.

- Lobo Blanco, a chief in the 1800s, who was killed in 1854.

- Viola Cordova (born 1937), a philosopher.

- Tammie Allen (born 1964), a potter.

|

See also

In Spanish: Jicarilla para niños

In Spanish: Jicarilla para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |