San Juan Basin facts for kids

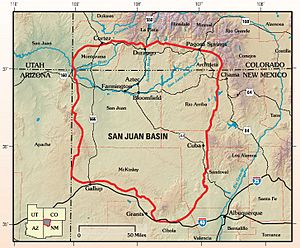

The San Juan Basin is a large bowl-shaped area of rock layers found near the Four Corners region in the Southwestern United States. This basin covers about 7,500 square miles (19,400 km2). It is located in northwestern New Mexico, southwestern Colorado, and parts of Utah and Arizona.

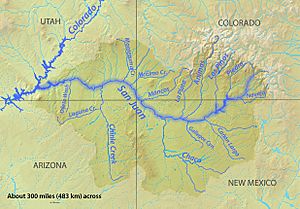

The San Juan Basin is like a giant, uneven dip in the Colorado Plateau. Its height changes a lot, with some parts nearly 3,000 feet (914 m) higher than others. Famous spots like Chaco Canyon are found here. The basin is west of the Continental Divide. Its main river is the San Juan River, which flows southwest and west to join the Colorado River in Utah. The climate here is very dry or semi-dry, getting about 15 inches (38 cm) of rain each year. The average temperature is around 50°F (10°C).

The San Juan Basin has been a big source of oil and natural gas since the early 1900s. Today, it has more than 300 oil fields and over 40,000 wells. By 2009, it had produced a huge amount of gas (42.6 trillion cubic feet) and oil (381 million barrels). This area is especially known for gas found in its coal-bed methane layers. The San Juan Basin has the largest coal-bed methane field in the world. It also ranks second globally for its total gas reserves.

Contents

How the Basin Formed

Ancient Mountain Building

Long, long ago, during the middle Paleozoic Era, the San Juan Basin area was part of a huge landmass called Laurentia. This was a supercontinent that included most of what is now North America. Another supercontinent, Gondwana, held most of the southern continents like South America and Africa.

Around 320 million years ago, Laurentia and Gondwana crashed into each other. This giant collision formed the supercontinent Pangea. This crash also caused several major mountain-building events. One of these was the Ouachita Orogeny. This event, caused by South America colliding with the Gulf region, created the Ancestral Rockies. These ancient mountains stretched through Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado. The Uncompahgre Mountain Range, which borders the San Juan Basin to the northeast, is part of these Ancestral Rockies.

Ocean Waters Arrive

Later, during the late Jurassic Period, the Farallon Plate slid under the North American Plate. This process, called subduction, caused the land in the middle of the continent to sink. This sinking created a large inland sea called the Inner Cretaceous Seaway (also known as the Western Interior Seaway). Water from the Arctic and Gulf regions flowed into the center of the continent. This changed the area from dry land to a shallow ocean basin.

Modern Mountain Building

From the late Cretaceous to the early Tertiary periods, the Farallon Plate continued to push against North America. This pressure caused the modern Rocky Mountains to rise up during the Laramide Orogeny.

Later, the pushing forces changed to pulling forces, which started forming the Rio Grande Rift. During this time, volcanoes were very active in the area. This volcanic activity shaped the land. Finally, more uplift in the northwest and continued layering of sediments brought the basin to how it looks today.

Parts of the Basin

The San Juan Basin is shaped like an uneven valley. It has three main parts: the Central Basin Platform, the Four Corners Platform, and the Chaco Slope. The basin is surrounded by other geological features. These include the Hogback Monocline to the northwest, the Archuleta Anticlinorium to the northeast, the Nacimiento Uplift to the east, and the Zuni Uplift to the south.

How Rock Layers Formed

Ancient Layers (Paleozoic)

Before the continents collided, layers of rock from the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian periods were laid down in different ocean environments. As the supercontinents crashed, the Paradox Basin sank, and the Uncompahgre highlands rose. This caused huge amounts of sediment to wash off the highlands through rivers during the Permian period.

The Rico Formation shows the change from ocean deposits to land deposits of the Cutler Formation. The Permian period continued to be a time of land deposits, including sand dunes formed by wind.

Middle Layers (Mesozoic)

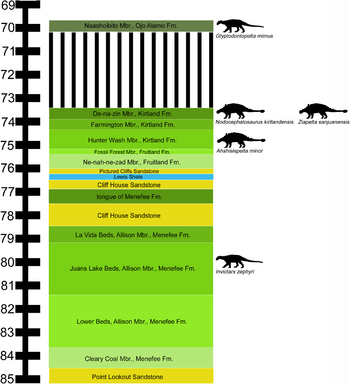

The Cretaceous period saw three big cycles of sea level rising and falling. The San Juan Basin was perfectly located to record these changes in its rock layers. The farthest west the sea reached was recorded by the Lewis Shale. As the shoreline finally moved back, it formed the Pictured Cliffs and the Fruitland Formation.

Newer Layers (Cenozoic)

When the Western Interior Seaway pulled back, it left behind many swamps, lakes, and flood plains. This created the coal-rich layers from the late Mesozoic and early Cenozoic (like the Fruitland Formation and the Kirtland Shale).

Volcanic activity during the Eocene and Oligocene periods created huge areas covered by volcanic ash and rocks. These volcanic fields were the source for Cenozoic layers like the Ojo Alamo (from the west) and the Animas and Nacimiento formations (from the northeast). Uplift in the northwest, along with more sediment being laid down (like the San Jose Formation), shaped the basin into its current form.

Rock Layers (Stratigraphy)

Very Old Layers (Precambrian)

We don't know much about the very oldest rocks from the Precambrian time. This is because they are hard to see at the surface and very few wells have drilled deep enough to reach them. These rocks are made of quartzite, schist, and granite. Younger Paleozoic rocks lie on top of them.

Ancient Layers (Paleozoic)

Not much is known about the rock layers from the Paleozoic Era. Out of more than 40,000 wells drilled in the San Juan Basin, only about 12 have gone deep enough to touch Paleozoic rocks. Also, these layers are hard to study because they don't show up well at the surface, and they change a lot from one place to another.

Devonian Period

- The Ignacio Formation has layers of quartzite, sandstone, and shale. It formed in the Late Devonian period when a sea spread eastward, covering the older Precambrian rocks.

- The Aneth Formation is made of dark limestone, clay-rich dolomite, and black shale or siltstone. This Late Devonian layer is found only deep underground.

- The Elbert Formation has two parts:

- The McCracken Sandstone Member has poorly sorted sandstones.

- The unnamed upper member has green shales, white sandstones, and thin limestone or dolomite layers.

- The Ouray Formation has fossil-rich (like brachiopods and crinoids) limestone or dolomite layers. These fossils show it was a marine environment in the Late Devonian.

Mississippian Period

- The Leadville Limestone formed in shallow and open ocean environments. This rock layer has produced over 50 million barrels of oil in Colorado and Utah.

- The Molas Formation has three parts, including red to brown siltstones and conglomerates from ancient soil and stream deposits.

- The Log Springs Formation is similar to parts of the Molas Formation.

Pennsylvanian Period

- The Pinkerton Trail (north) and the Sandia (south) formations have grey limestone and shale layers. They formed as a sea spread southwest.

- The Paradox Formation has complex layers of salt and non-salt rocks. These layers are great at trapping hydrocarbons (oil and gas).

- The Honaker Trail Formation has limestone and dolomite at the bottom, topped by sandstones from the northern Uncompahgre highlands.

- The Madera Group is the southern version of the Paradox and Honaker Formations. It includes the Gray Mesa Formation and the Atrasado Formation.

- The Rico Formation shows the change from ocean layers to land layers. It has conglomerates and sandstones mixed with ocean shales and fossil-rich limestones.

Permian Period

- The Cutler Group formed from sediments washed down from highlands to the north and northeast. It includes sandstones, conglomerates, and some siltstones and mudstones. It has several formations:

- The Halgaito Formation has alternating ocean-edge and river sediments.

- The Cedar Mesa Sandstone varies, with layers from evaporite, river, tidal-flat, and sabkha environments.

- The Organ Rock Formation has siltstones and sandstones from coastal plains and rivers.

- The De Chelly Sandstone is made of sandstones from ancient sand dunes.

- The Yeso Formation has two parts:

- The Meseta Blanca Sandstone Member has classic sand dune deposits.

- The San Ysidro Member has sandy layers mixed with gypsum, showing complex changes between sand dunes, coasts, and shallow seas.

- The Glorieta Sandstone has buff to white sandstones, also from sand dunes.

- The San Andres Limestone (also called Bernal Formation) has thick limestone and dolomite layers mixed with sandstone or shale.

Middle Layers (Mesozoic)

Triassic Period

- The Moenkopi Formation and the upper Chinle Formation sit on top of Permian rocks. They are made of sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone from land environments.

Jurassic Period

- Rocks from this time, like the Morrison Formation, include continental sandstone and siltstone, and marine limestone and anhydrite deposits.

Cretaceous Period

The Cretaceous-aged rocks are the best understood and most productive for oil and gas in the San Juan Basin. The western edge of the Inner Cretaceous Seaway was along the San Juan Basin. The three major times the sea rose and fell during this period are recorded in the middle to upper Cretaceous layers.

- The Dakota Sandstone Formation is an early Cretaceous layer of river sandstones. These layers gradually change into the Mancos Shale above them.

- The Mancos Shale represents deeper ocean deposits as the Inner Cretaceous Seaway made its first big advance. It has three main parts:

- The Graneros Shale contains sandstone, bentonite, and limestone layers.

- The Greenhorn Limestone has alternating layers of limestone and shale, formed when the sea was at its highest level.

- The Juana Lopez Member has fossil-rich shale layers.

- The Mesaverde Group formed as the Inner Cretaceous Seaway moved northeast, depositing the Point Lookout Sandstone. Then it moved southwest again, depositing the Cliff House Sandstone.

- The Lewis Shale has grey shales mixed with sandstone and limestone. These are deeper ocean deposits as the seaway continued to move southwest. This layer shows the farthest west the Inner Cretaceous Seaway reached.

- The Pictured Cliffs Sandstone has two layers: a lower one with mixed shales and sandstones as the sea began to retreat, and an upper one with massive sandstone layers as the sea made its final retreat.

- The Fruitland Formation is made of shale, siltstone, and, very importantly, coal. These formed from swamps, rivers, lakes, and flood plains.

- The Kirtland Formation has two layers: a lower shale layer similar to the upper Fruitland but without coal (so it's separate), and upper shale to sandstone layers from rivers.

Newer Layers (Cenozoic)

- The Ojo Alamo Formation has conglomerates and sandstones, likely from the west.

- The Animas Formation in the north gradually changes into the Nacimiento Formation in the south. These layers are from volcanoes, specifically the San Juan Volcanic Field.

- The Eocene-aged San Jose Formation has sandstones and shales.

Oil and Gas in the Basin

The San Juan Basin has lots of energy resources, including oil, gas, coal, and uranium. It has produced from over 300 oil fields and nearly 40,000 wells. Most of these get their oil and gas from rocks formed during the Cretaceous period. About 90% of the wells are in New Mexico. By 2009, the basin had produced 42.6 trillion cubic feet of gas and 381 million barrels of oil.

A Brief History

The first oil well in the San Juan Basin was drilled in 1911. It was only 100 meters deep and produced 12 barrels of oil per day. Ten years later, in 1921, the first gas well was drilled. It was 300 meters deep and led to a gas pipeline being built to carry gas to nearby cities. Many more oil and gas discoveries followed, making people very interested in the San Juan's resources.

In the 1930s, the first pipeline was built to send gas outside the basin. The 1980s brought the discovery of coal-bed methane resources, which led to a big increase in drilling during the 1980s and 1990s. Production has now leveled off, but the basin is still actively producing today.

Paleozoic Oil and Gas

While most of the oil and gas comes from Cretaceous rocks, the older Paleozoic rocks in the Four Corners Platform have also produced from over two dozen fields. These fields get oil and gas from Devonian, Mississippian, and Pennsylvanian-aged layers. The Paleozoic layers get deeper towards the northeast. Because of this, Paleozoic fields produce gas in the northeast and oil in the southwest. Future efforts in Paleozoic layers will focus on natural gas.

Mesozoic Oil and Gas

Cretaceous-aged rocks are the main source of gas and oil in the San Juan Basin. Nearly 250 of the more than 300 fields get their resources from Upper Cretaceous layers. Major oil targets include the Dakota Sandstone, Gallup Sandstone, Tocito Sandstone, and El Vado Sandstone Member. The oil in these layers came from the dark, organic-rich marine shale of the Mancos Formation below them. Most of these oil fields are now running low on oil.

Major gas targets in the San Juan Basin include the Dakota Sandstone, Point Lookout Sandstone, and Pictured Cliffs Sandstone. Gas is often trapped in specific rock layers, mostly in the Central Basin Platform.

Oil Fields

- The Dakota Sandstone has nearly 40 oil fields. Each has produced millions of barrels of oil.

- The Gallup Sandstone has about four oil fields. These have produced from tens of thousands to millions of barrels of oil.

- The Tocito Sandstone Lentil of the Mancos Shale has about 30 fields. These are the best Cretaceous oil reservoirs, having produced over 150 million barrels of oil.

- The El Vado Sandstone Member of the Mancos Shale has produced from nearly 40 fields, mostly in the Central Basin Platform. This member alone has produced over 40 million barrels of oil.

Gas Fields

- The Dakota Sandstone holds gas in offshore marine sandstones, trapped by marine shales. Special fracturing is needed to get the gas out.

- The Pictured Cliffs Sandstone formed from retreating seas. Gas is stored in porous sandstones and trapped by mud or siltstones. Production depends on natural cracks in the rock.

- The Point Lookout Sandstone is similar to the Pictured Cliffs Sandstone in how it holds gas.

Coal-bed Methane

- The Fruitland Formation holds the San Juan Basin's large supply of methane-rich coal beds. Methane is found in thousands of coal beds throughout this formation. Like Paleozoic gas fields, the amount of gas increases towards the northeast. By 2009, it had produced 15.7 trillion cubic feet of gas, making it the largest coal-bed methane field in the world.

Methane Cloud

In 2014, NASA scientists reported finding a methane cloud over the Basin. This cloud covered about 2,500 square miles (6,475 km2). They found this by looking at data from a European Space Agency instrument collected between 2002 and 2012.

The report concluded that the methane likely came from existing gas, coal, and coalbed methane mining and processing in the area. Between 2002 and 2012, the region released 590,000 metric tons of methane each year. This amount was almost 3.5 times higher than what was generally estimated by the European Union’s Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research.

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |