Dakota Formation facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dakota Formation / GroupStratigraphic range: Cenomanian |

|

|---|---|

Road cut into the lower Dakota Group at crest of Dinosaur Ridge, near Golden, Colorado

|

|

| Type | Geologic formation or group |

| Sub-units | Formation (type: Nebraska, Kansas): D/Johnson Clay Member J/Terra Cotta Clay Member Formation (Iowa): Romeroville Sandstone Pajarito Formation Mesa Rica Sandstone |

| Underlies | Graneros Shale (Great Plains) Mancos Shale (Southwest) |

| Overlies | Precambian (Sioux Quartzite), Permian, Early Cretaceous, (Lytle), and Jurassic (Morrison Formation) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | varying proportions of terrestrial sandstone, mudstone, and clay |

| Other | marine shale, lignite, coal |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 42°18′25″N 96°27′14″W / 42.307°N 96.454°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 38°54′N 66°24′W / 38.9°N 66.4°W |

| Region | Great Plains, Rocky Mountains, Colorado Plateau, Rio Grande rift valley |

| Country | |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Dakota City, Nebraska |

| Named by | Meek and Hayden |

| Year defined | 1862 |

The Dakota is a famous set of rock layers made of sandstones, mudstones, clays, and shales. These rocks were laid down during the Mid-Cretaceous period, when a huge inland sea, called the Western Interior Seaway, was forming across North America.

You can find the Dakota rocks in many places. They stretch from British Columbia and Alberta in Canada, all the way through states like Montana, Wisconsin, Colorado, Kansas, Utah, and Arizona in the United States. These rocks are well-known for forming colorful landscapes in the Rocky Mountains and the Great Plains. They are also special because they hold amazing fossils, like dinosaur footprints and ancient leaves from early deciduous trees.

The Dakota rocks sit on top of much older rocks. This is because a lot of the older rocks wore away during the Jurassic and Triassic periods. The Dakota is usually the oldest Cretaceous rock layer you can see in the northern Great Plains and the Desert Southwest. It often contains sandy layers from shallow seas or beaches, along with muddy layers from ancient mudflats and rivers.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Dakota was first used in 1862 by scientists F.B. Meek and F.V. Hayden. They named it after the distinct red sandstone layers they saw near Dakota City, Nebraska. When they first used the name, "group" meant what "formation" means today.

Dakota Formation

The main name for these rocks in the Great Plains is the Dakota Formation. A "formation" is a specific rock layer that geologists can map. In some western areas, like northeast Utah, the Dakota is also called a formation because it gets thinner there and doesn't include marine shales. In the San Juan Basin and other areas in the Southwest, it's often called the Dakota Sandstone. This is a common informal name for the sandy parts of the unit.

Dakota Group

Sometimes, the Dakota is called the Dakota Group. A "group" means it includes several different rock formations that are related. This name is used in places like the Dakota Hogback in Colorado and Wyoming, the Colorado Plateau, and the Denver Basin. In these areas, the Dakota Group can include older rocks than elsewhere. For example, the Lytle Formation is part of the Dakota Group in Colorado, and it's older than most other Cretaceous rocks in the area.

Dakota Aquifers

When the Dakota sandstone layers are close to the surface, they can hold a lot of water. These areas are called Dakota Aquifers. They are very important sources of water in parts of the Great Plains and the Southwest. They are even bigger than the famous Ogallala Aquifer. These aquifers are known for their artesian properties, meaning water can flow out of them under its own pressure.

Oil and Gas

When the Dakota sands are buried deep underground, like in the Denver Basin, they can contain valuable oil and natural gas. These are called hydrocarbon reserves. Drillers look for these sands to find energy resources.

How the Dakota Rocks Formed

The rocks of the Dakota Formation started to form during the early Late Cretaceous period, about 100 million years ago. This was a big change because for over 100 million years before, rocks in this area had been wearing away.

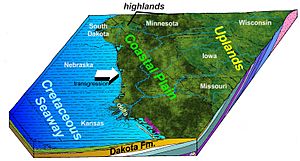

This change happened because the Western Interior Seaway began to form. As the sea level rose, the mouths of rivers also rose. This made the rivers flow slower, so they dropped their sediment (like sand and mud) further inland.

Scientists can tell that ancient rivers flowed west and southwest from areas near today's Great Lakes. As the sea level kept rising, the rivers deposited sediment further and further east. This is why the sandstones in Kansas have bits of older rocks, but the sandstones in Iowa have bits of even older, crystalline rocks. This means the rivers had worn away all the younger rocks by the time they reached Iowa.

The very top layers of the Dakota Formation were laid down right along the coast. This is shown by some marine invertebrate fossils found there. Fossils of plants, coal, and kaolinite clay show that the climate was warm and wet when the Dakota rocks were forming. Some ancient soils even show that there were huge forests on floodplains.

What the Dakota Rocks Are Made Of

The Dakota rocks are mostly known for their huge layers of sandstone. These sandstones can be red, gray, yellow, or white. The sand was carried by rivers or piled up on beaches and dunes. Later, minerals like red iron oxide or white calcite glued the sand grains together, making the rock hard. Some sandstone is soft and crumbly, while other parts are very hard.

The amount of sandstone can vary a lot, from just 5% to 80% of the rock unit. The rest of the Dakota is usually layers of mudstone and clay. These were deposited in floodplains, swamps, and river mouths. Like the sand, the mud was changed by groundwater, which added iron oxide or calcite. These mudstones can be dark red, light red, gray, yellow, or white.

Because the Dakota environment was often low-lying, wet, and lush, lignite (a type of soft coal) and harder coal formed in some areas.

Shale from the ancient sea is also part of the Dakota layers. It's less common in the eastern parts, but more common where the sea was deeper. These different types of rock layers, from land-formed sandbanks and mudflats to marine shales, can be found for thousands of miles.

Two Sides of the Ancient Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway started to spread south from what is now the Arctic Ocean in the Early Cretaceous period. It eventually connected with a shorter arm coming north from the Gulf of Mexico. By about 100 million years ago, this huge sea had completely divided North America in half!

On the eastern side of this seaway, the sediments that became the Dakota Formation were laid down as coastal sands and silts. As the sea got deeper and wider, this eastern shoreline moved further east.

Meanwhile, on the western side of the seaway, rivers carried sediments east and northeast from mountains near what is now the Nevada-Utah border. These western sediments also formed coastal sands and silts. They are similar to the Dakota Formation on the eastern side, but they came from different rivers flowing in opposite directions. So, while they are "equivalent" in time, they are not exactly the same rock layers.

For example, in Wyoming, some rocks that used to be called Dakota are now part of the Cloverly Formation. In Colorado, the lower, land-based parts of the Dakota Group are sometimes called the Lytle Formation, and the near-shore marine parts are called the South Platte Formation.

Useful Resources from the Dakota

The Dakota rocks have provided several important resources over time.

Energy Resources

The shales and mudstones in the Dakota Group can be a source of oil and gas. The sandstone layers can trap these resources, making them valuable for energy. This is why the Dakota Group is an important source of oil and gas in the Denver Basin.

Water Resources

When the Dakota sandstones are close to the surface, they act as important water sources. The Dakota Aquifers provide crucial water supplies in many parts of the Plains, especially in areas not covered by the Ogallala Aquifer.

Building Materials and Minerals

Since the Dakota Formation formed on land (unlike many other sea-formed rocks in the Plains), it has unique resources.

- Coal: Lignite coal formed in the Dakota rocks. Early American settlers briefly mined it for fuel in the 1800s.

- Iron: The ancient swampy environments of the Dakota period led to the formation of iron-rich rocks like hematite and limonite. These "ironstone" rocks were sometimes used as building materials. Historic buildings from the 1860s, like Fort Harker (Kansas) and Fort Larned, were built with this strong, colorful stone.

- Clay: The Dakota clays are dug up and used to make tiles and bricks.

- Uranium: Uranium is also found in the Dakota sandstone. It was deposited there by water flowing through the aquifers.

Ancient Environment and Fossils

The sands and muds of the Dakota show us what the ancient world was like. It was a wet lowland with rivers, floodplains, and beaches. The shoreline was wavy, with river deltas and salty bays. Groundwater quickly deposited iron oxide and calcite, which hardened the material and helped preserve evidence of the ancient plants and animals.

For example, sandstone with dinosaur tracks found near Denver shows that the sea sometimes moved away from the area, creating temporary land bridges.

- Dakota Fossils of Land Environments

-

Iron-cemented leaf imprint (Ellis County, Kansas); evidence of boggy sand near deciduous trees

-

Marine mollusk shell (Ellis County, Kansas); evidence of sandy wave-washed beach

-

Dinosaur beach tracks (Dinosaur Ridge); temporary, wide land bridge across the seaway

Dinosaur Fossils

Dinosaur fossils are quite rare in the Dakota Formation, but some have been found, mostly in Kansas and Colorado. The most famous place to see Cretaceous dinosaur fossils in Colorado is Dinosaur Ridge.

One of the best dinosaur fossils found is a partial skeleton of a nodosaurid ankylosaur called Silvisaurus condrayi. Other ankylosaur bones might also belong to Silvisaurus. Scientists have also found fossil dinosaur tracks, including those from meat-eating theropods and ankylosaurs. A large leg bone from a plant-eating ornithopod dinosaur was found in Nebraska, along with more dinosaur tracks in Colorado.

- cf. Troodon sp.

- cf. Paronychodon (? troodontid indet)

- cf. Richardoestesia sp. (theropod indet)

- ? Barosaurus lentus

- Silvisaurus condrayi – "Partial skeleton with skull, sacrum."

Pterosaurs

| Pterosaurs of the Dakota Formation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxon | Presence | Description | Images | |

Suborder:

|

Known from both early and late Cretaceous rock layers in the Dakota Group. Found at the John Martin Reservoir in Colorado. | Specimens are kept at the Dinosaur Tracks Museum, at the University of Colorado at Denver. | ||

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |