Kit Carson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Christopher Houston "Kit" Carson

|

|

|---|---|

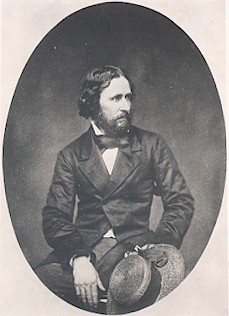

Kit Carson in the 1860s, judging by the uniform

|

|

| Born | December 24, 1809 Tate's Creek, Madison County, Kentucky

|

| Died | May 23, 1868 (aged 58) Fort Lyon, Colorado

|

| Cause of death | Aortic aneurysm |

| Resting place | Kit Carson Cemetery Taos, New Mexico |

| Nationality | American |

| Citizenship | American |

| Occupation | Mountain man Frontiersman Guide Indian agent United States Army officer |

| Known for | Opening the American West to white settlement |

| Spouse(s) | Waanibe Making-Out-Road Josefa Jaramillo |

| Children | With Waanibe: Adaline Daughter, died young With Jaramillo: Charles Carson, died young William Julian Carson Teresina Carson Christobal Charles Carson Charles Christopher Carson Rebecca Carson Estifanita "Stella" Carson Josefita Carson |

| Parent(s) | Lindsay Carson Rebecca Robinson |

| Signature | |

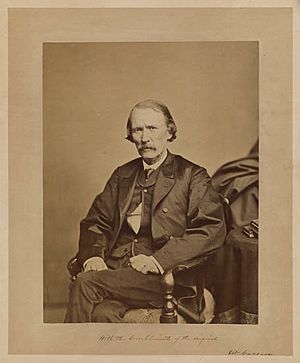

Christopher Houston "Kit" Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was a famous American frontiersman. He worked as a mountain man, a guide, an Indian agent, and an officer in the United States Army. Kit Carson helped open up the American West for new settlers. During his time, he was a well-known celebrity across the United States. Today, many people remember him as a folk hero.

Carson started his adult life in 1829 as a mountain man. For about ten years, he trapped beaver for the fur trade. During these years, Carson often had to fight Native Americans to protect himself from danger. When the fur trade slowed down in the 1840s, Carson looked for new work.

In 1842, an Army officer named John C. Frémont hired Carson. Carson guided Frémont on three important expeditions into the West. These trips helped map and describe new areas of the West. Frémont's reports made Carson a hero and were read by many Americans. Carson became a celebrity across the country. His adventures were even turned into popular stories called dime novels.

In 1853, Carson became an Indian agent in northern New Mexico. His job was to help keep peace between the Utes and Apaches. He made sure they were treated fairly and received the food and clothing they needed. In 1861, the American Civil War began. Carson left his job and joined the Union Army. He led the New Mexico Volunteer Infantry. His forces fought Confederates at Valverde, New Mexico. Carson was later promoted to colonel and then to brigadier general.

Carson was married three times. His first two wives were Native Americans, and his third wife was Mexican. He had ten children. He died in 1868 at Fort Lyon, Colorado. He is buried in Taos, New Mexico, next to his third wife, Josefa Jaramillo.

Contents

- Carson's Learning Journey

- Kit Carson's Early Life

- Becoming a Mountain Man

- Exploring with John Charles Frémont

- The Bear Flag Revolt

- The Mexican-American War

- Books and Stories About Kit Carson

- Kit Carson as an Indian Agent

- Carson's Military Life

- Campaign Against the Navajos

- The Battles of Adobe Walls

- Death and What He Left Behind

- Images for kids

- See also

Carson's Learning Journey

Kit Carson could not read or write for most of his life. This is called being illiterate. He felt a bit embarrassed about it and tried to keep it a secret. However, he admired people who could read and write. In 1856, he told his life story to an Army officer who wrote it down for him. Carson explained that he left school when he was very young.

Carson loved having others read to him. He enjoyed the poetry of Lord Byron. He also liked a book about William the Conqueror. William the Conqueror's favorite saying was "By the splendor of God." Carson liked this saying so much that he used it as his own. He was known for never using stronger words.

Later in life, Carson learned to write "C. Carson." It was very hard for him. On official papers, he would make his mark, and a clerk would witness it. Carson could easily speak English, Spanish, and French.

He also knew many Native American languages, including Navajo, Apache, and Comanche. He even knew the sign language used by mountain men. Very late in his life, he learned to read a little and could recognize his name when it was printed.

Kit Carson's Early Life

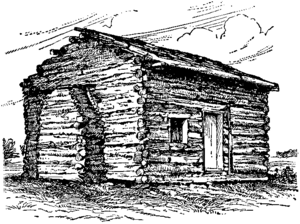

Kit Carson was born in a log cabin in Tate's Creek, Madison County, Kentucky. This was on Christmas Eve in 1809. His parents were Lindsay Carson and Rebecca Robinson. Kit was their sixth child.

His family moved to Missouri when he was a baby. In Missouri, families often faced danger from Native American attacks. They had to learn ways to protect themselves. After his father died in 1818, Kit's mother remarried. Kit became a wild teenager. His stepfather made him work in a saddle-making shop in Franklin, Missouri. The Carson family knew the Daniel Boone family.

The Carson family in Missouri was always ready for Native American attacks. Their cabins were "forted," meaning they had tall fences called stockades built around them. These stockades kept the people inside safe. During the day, men worked in the fields near the cabins. Some men carried weapons to protect the workers.

Becoming a Mountain Man

Franklin, Missouri, was the start of the Santa Fe Trail. This was a path for many settlers heading west. Kit heard exciting stories about the West from mountain men returning home. Kit did not like making saddles. In August 1826, he ran away from home. He went west with the mountain men, traveling the Santa Fe Trail to Santa Fe, New Mexico. They arrived in November 1826. Kit spent that winter in Taos, New Mexico. Taos would later become Carson's home.

Between 1827 and 1829, Carson worked as a cook, translator, and wagon driver in the southwest. He also worked at a copper mine near the Gila River in southwestern New Mexico.

In August 1829, nineteen-year-old Carson joined trapper Ewing Young and his mountain men. They went on a fur-hunting expedition to Arizona and California. This was Carson's first professional job as a mountain man. He gained a lot of experience as a trapper on this trip. Young helped shape Carson's early life in the mountains.

Carson returned to Taos in 1829. He joined another expedition in 1831, led by Thomas Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick and his trappers went north to the central Rocky Mountains. Carson would hunt and trap in the West for about ten years. He became known as a dependable man and a skilled fighter.

Carson traveled through many parts of the American West, collecting furs. At this time, men wore hats made of beaver fur. Carson trapped beaver for the fur trade. He sometimes worked with famous mountain men like Jim Bridger.

Mountain men faced many dangers. These included biting insects, bad weather, and various diseases. There were no doctors where mountain men worked. They had to fix their own broken bones, treat their wounds, and take care of themselves. Native Americans were also a constant danger. Even a friendly Native American could quickly become an enemy.

The mountain man's main food was buffalo. They wore clothes made from deer skins that had become stiff after being left outdoors. These stiff deer skin suits offered some protection against enemy weapons.

Around 1840, the fur trade began to decline. Well-dressed men in London, Paris, and New York City started wanting silk hats instead of beaver hats. Also, the mountain men had trapped almost all the beavers in North America. Trappers were no longer needed as much. Carson knew it was time to find other work.

In 1841, he was hired at Bent's Fort in Colorado. This fort was a very important place in the West. Hundreds of people worked or lived there. Carson hunted buffalo, antelope, deer, and other animals. He was paid one dollar a day. He returned to Bent's Fort several times to provide meat for the people living there. In April 1842, Carson went back to his childhood home in Missouri. He made this trip to leave his daughter Adaline with relatives.

Exploring with John Charles Frémont

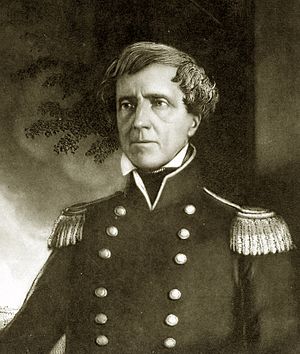

In 1842, Carson was returning from Missouri when he met John C. Frémont on a steamboat on the Missouri River. Frémont was an officer in the United States Army. Carson had little money at the time. Frémont hired Carson as a guide for $100 a month.

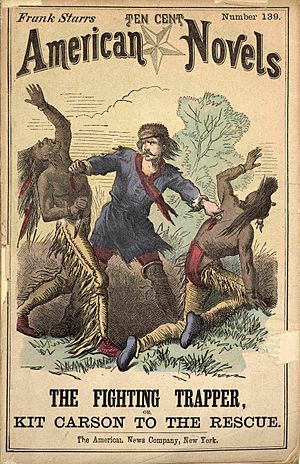

In 1842, Carson guided Frémont across the Oregon Trail to Wyoming. This was their first trip into the West. The goal was to map and describe the Oregon Trail. A guidebook and maps would be printed for settlers. Frémont praised Carson in his government reports. Because of this, Carson became well known across the United States. He became the hero of many popular, cheap books called dime novels.

In 1843, Frémont asked Carson to join his second expedition. Carson agreed. He guided Frémont across part of the Oregon Trail to the Columbia River in Oregon. The trip's purpose was to map and describe the Oregon Trail further. They also traveled to Great Salt Lake in Utah. The men then headed to California. They faced bad weather in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Carson's good judgment and guiding skills saved the men.

The expedition then went into California. This was against the law and dangerous because California was Mexican territory. The Mexican government ordered Frémont to leave. Frémont eventually went back to Washington, D.C. The government liked his reports, but ignored his illegal trip into Mexico. Frémont was made a captain. Newspapers called him "The Pathfinder."

In 1845, Carson guided Frémont on their third and last expedition. They went to California and Oregon. Frémont had scientific plans, but the trip seemed to have a political purpose. Frémont might have been working under secret government orders. President Polk wanted the area of Alta California for the United States. Once in California, Frémont started to stir up American settlers. The Mexican government ordered him to leave. Frémont went north to Oregon and camped near Klamath Lake. Messages from Washington, D.C., made it clear that President Polk wanted California.

The Bear Flag Revolt

In June 1846, Frémont and Carson took part in a California uprising against Mexico. This was called the Bear Flag Revolt. Mexico ordered all Americans to leave California. The Americans did not want to go. They declared California an independent republic.

American settlers in California wanted to be free from the Mexican government. They felt brave enough to oppose Mexico because Frémont and his troops were there to help.

Frémont wrote an oath of allegiance. He and his men were able to offer some protection to the Americans.

Frémont worked hard to help the United States gain California. He became its military governor. In 1847 and 1848, Carson made two quick trips to Washington, D.C., carrying messages and reports. In 1848, he brought news of the California Gold Strike to the nation's capital.

The Mexican-American War

The Mexican–American War was a conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. America won this war. Under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexico had to sell the territories of Alta California and New Mexico to the United States.

While Carson was not a regular soldier, one of his most famous adventures happened during this war. In December 1846, General Stephen W. Kearny ordered Carson to guide him and his troops. They traveled from Socorro, New Mexico to San Diego, California. Mexican soldiers attacked Kearny and his men near the village of San Pasqual, California.

There were too many Mexican soldiers. Kearny knew he could not win. He ordered his men to take cover on a small hill. Kearny then sent Carson, a naval lieutenant named Beale, and a Native American scout to get help. The three left on the night of December 8 for San Diego, which was about 25 miles (40 km) away.

By December 10, Kearny thought help would not arrive. He planned to break through the Mexican lines the next morning. That night, 200 American soldiers on horseback arrived in San Pasqual. They cleared the area and drove the Mexicans away. Kearny was in San Diego by December 12. After the Mexican–American War, Carson went back to Taos to start a ranch.

Books and Stories About Kit Carson

Carson's fame grew across the United States through government reports, dime novels, newspaper stories, and word of mouth. The dime novels celebrated Carson's adventures, but they often made things sound more exciting than they really were.

In 1847, the first story about Carson's adventures was printed. It was called An Adventure of Kit Carson: A Tale of the Sacramento. It appeared in Holden's Dollar Magazine. Other stories were also printed, such as Kit Carson: The Prince of the Goldhunters and The Prairie Flower.

In 1856, Carson told his life story to someone who wrote it down. This book is called Memoirs. Some say Carson forgot dates or got them wrong. The handwritten story was lost when it was taken East to find a professional writer. It was found in a trunk in Paris in 1905 and later printed.

Kit Carson as an Indian Agent

In 1853, Carson became the United States Indian agent for the Utes. These people lived across northern New Mexico. The Jacarilla Apaches and the Puebloans at the Rio Grande also came under Carson's care. Carson's job was to keep peace between the southwestern tribes. He also had to find and punish anyone who committed crimes. Carson was known for being honest and fair as an Indian agent.

Carson wanted the government to set aside large areas of land far from white settlements. These lands would be called reservations. They were meant only for Native Americans. He thought Native Americans should be taught agriculture. However, it was very hard to teach nomadic hunters to settle in one place and farm. He believed his plans would help these people avoid becoming extinct.

Carson left his job as Indian agent when the American Civil War started in April 1861. He joined the Union Army to lead the 1st New Mexico Volunteer Infantry.

Carson's Military Life

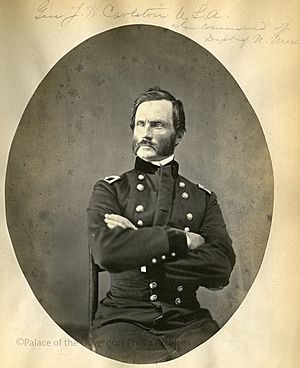

In April 1861, the American Civil War began. Carson left his job as an Indian agent and joined the Union Army. He was made a lieutenant. He led the 1st New Mexico Volunteer Infantry and trained new soldiers. In October 1861, he was made a colonel. The Volunteers fought the Confederate forces at Valverde, New Mexico, in February 1862. The Confederates won this battle, but they were later defeated.

Once the Confederates were driven from New Mexico, Carson's commander, Major James Henry Carleton, focused on the Native Americans. Carleton led his forces deep into Mescalero Apache territory. The Mescaleros were tired of fighting and asked for Carson's protection.

Carleton placed these Apaches on a remote reservation east of the Pecos River. Carson resigned from the Army in February 1863. However, Carleton refused to accept his resignation. He wanted Carson to lead a campaign against the Navajo.

Carleton had chosen a harsh place on the Pecos River for his reservation. This reservation was called Bosque Redondo (Round Grove). He chose this site for the Apaches and Navajos because it was far from white settlements. He also thought its remoteness would stop white settlers from moving there.

The Mescalero Apaches walked 130 miles to the reservation. By March 1863, four hundred Apaches had settled near Fort Sumner. Others had fled west to join other Apache groups. By mid-summer, many of these people were planting crops and farming.

On July 7, Carson, though not eager for the task, began the campaign against the Navajo tribe. His orders were similar to those for the Apache roundup: he was to shoot all males on sight and take women and children captive. No peace treaties were to be made until all Navajo were on the reservation.

Carson searched far and wide for the Navajo. He found their homes, fields, animals, and orchards. But the Navajo were very good at disappearing quickly and hiding in their vast lands. The roundup was very frustrating for Carson. He was in his 50s, tired, and unwell.

By autumn 1863, Carson started burning Navajo homes and fields and taking their animals. The Navajo would starve if this destruction continued. One hundred eighty-eight Navajo surrendered. They were sent to Bosque Redondo. Life at Bosque was difficult. The Apaches and Navajos fought, and the water in the Pecos River caused cramps and stomach aches. Residents had to walk about twelve miles to find firewood.

Carson wanted a break from the campaign for the winter. Major Carleton refused. Kit was ordered to invade the Canyon de Chelly. Many Navajos had taken refuge there.

The Canyon de Chelly was a sacred place for the Navajo. They believed it would be their safest hiding place. Three hundred Navajo hid on the canyon rim at a spot called Fortress Rock. They resisted Carson's invasion by building rope ladders, bridges, and lowering water pots into a stream. They also stayed out of sight.

In January 1864, Carson swept through the 35-mile Canyon with his forces. He cut down thousands of peach trees in the Canyon. Few Navajo were killed or captured. However, Carson's invasion showed the Navajo that white men could invade their country anytime. Many Navajo surrendered at Fort Canby.

By March 1864, there were 3,000 refugees at Fort Canby. Another 5,000 arrived in the camp. They were suffering from intense cold and hunger. Carson asked for supplies to feed and clothe them. The thousands of Navajo were then led to Bosque Redondo.

In Navajo history, this terrible journey is known as The Long Walk. By 1866, reports showed that Bosque Redondo was a complete failure. Major Carleton was fired. Congress started investigations. In 1868, a treaty was signed, and the Navajo were allowed to return to their homeland. Bosque Redondo was closed.

The Battles of Adobe Walls

On November 25, 1864, Carson led his forces against southwestern tribes at the First Battle of Adobe Walls in the Texas panhandle. Adobe Walls was an abandoned trading post. Its inhabitants had blown it up to prevent hostile Native Americans from taking it over. The First Battle involved the United States Army and many Kiowas, Comanches, and Plains Apaches. It was one of the largest battles fought on the Great Plains.

The battle was a major defeat for the Native Americans. It also led the U.S. military to take final actions to defeat the Native Americans. Within a year, the long war between whites and Native Americans in Texas ended.

The battle happened because General Carleton believed Native Americans were responsible for ongoing attacks on white settlers along the Santa Fe Trail. He wanted to punish these attackers and brought in Carson to do the job. Most of the Army was busy elsewhere during the American Civil War. So, the protection settlers needed was almost nonexistent. They were begging for help. Carson led 260 cavalry, 75 infantry, and 72 Ute and Jicarilla Apache Army scouts. He also had two mountain howitzer cannons.

On the morning of November 25, Carson found and attacked a Kiowa village with 176 lodges. After destroying it, he moved toward Adobe Walls. Carson found other Comanche villages nearby. He realized he would face a very large force of Native Americans. The battle lasted four to five hours. When Carson ran low on ammunition, he ordered his men to retreat to a nearby Kiowa village. There, they burned the village and many fine buffalo robes.

Some consider this battle to be Carson's finest moment. It is thought to be one reason why the Kiowas and Comanches sought peace in 1865. The First Battle at Adobe Walls was the last time the Comanche and Kiowa forced American troops to retreat from battle. Adobe Walls marked the beginning of the end for the plains tribes and their way of life.

A decade later, the Second Battle of Adobe Walls was fought on June 27, 1874. It was between 250 to 700 Comanche and a group of 28 hunters defending Adobe Walls. After a four-day siege, the hundreds of Native Americans left. The Second Battle led to the Red River War of 1874-1875. This war resulted in the final relocation of the Southern Plains Indians to reservations in Oklahoma.

Death and What He Left Behind

Carson left the Army on November 22, 1867. He moved his family to a small settlement in Colorado called Boggsville. He had no money. He sold his house in Taos. He wanted to build a ranch. In January 1868, he became the superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Colorado Territory. He was called to Washington, D.C., in February 1868 with Ute chiefs to make a treaty.

Carson was very ill and doubted he could make the trip. But he felt responsible to the chiefs and went anyway. He asked doctors on the East Coast about his health. They gave him little hope of getting better. He toured New York City, Philadelphia, and Boston. His last photograph was taken in Boston.

He returned home in April 1868. Josefa had given birth to their last child, Josefita. It was a difficult birth. Josefa died within two weeks. Carson missed her very much. His health got worse. He needed chloroform to ease the pain. Carson made his will on May 15, 1868, at Fort Lyon. He named Thomas Boggs as the person to manage his estate. Any money from his estate would be used to support his children.

Carson had been diagnosed with an aortic aneurysm. He died on May 23, 1868, at Fort Lyon, Colorado. He was 58 years old. An officer's wife offered her wedding dress to line Carson's coffin. The women of the fort used cloth flowers from their hats to decorate his coffin. Carson and Josefa were first buried in Boggsville. They were later moved in 1869 and buried in Taos, New Mexico.

Carson's home in Taos is now a museum run by the Kit Carson Foundation. A monument was put up in the plaza at Santa Fe by the New Mexico Grand Army. In Denver, a statue of Kit Carson on horseback can be found on the Mac Monnies Pioneer Monument. Another statue of him on horseback is in Trinidad. A national forest in New Mexico was named after Carson, as well as a county in Colorado. A river in Nevada is named for Carson, as well as the state's capital, Carson City. Fort Carson, an army training post near Colorado Springs, was named for him during World War II by a vote of the men training there.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Kit Carson para niños

In Spanish: Kit Carson para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |