Gadsden Purchase facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Gadsden Purchase of 1854

Venta de La Mesilla

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expansion of United States | |||||||||

| 1853–1854 | |||||||||

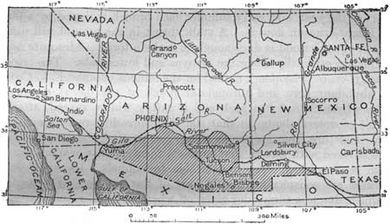

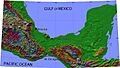

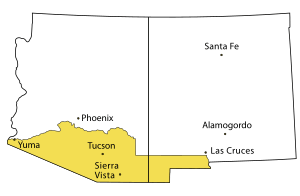

The Gadsden Purchase and main cities |

|||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

|

• 1854

|

76,845 km2 (29,670 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Federal republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• March 4, 1853 – March 4, 1857

|

Franklin Pierce | ||||||||

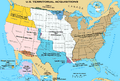

| Historical era | Westward expansion and Manifest Destiny | ||||||||

| 1846–1848 | |||||||||

|

• Treaty drafted

|

30 December 1853 | ||||||||

|

• Treaty approved by U.S. Senate

|

April 25, 1854 | ||||||||

|

• Treaty in effect

|

30 June 1854 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | United States | ||||||||

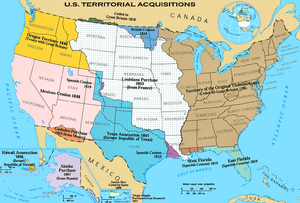

The Gadsden Purchase (also known as la Venta de La Mesilla in Mexico) was a deal where the United States bought a large piece of land from Mexico. This land, about 29,670-square-mile (76,800 km2) (that's like 19 million acres!), is now part of southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. The agreement was made official on June 8, 1854, through a document called the Treaty of Mesilla.

The main reason the U.S. wanted this land was to build a transcontinental railroad. This railroad would connect the eastern and western parts of the country. A southern route was preferred because it had flatter land. The Southern Pacific Railroad later built this route in the 1880s. The purchase also helped solve some other disagreements about the border between the two countries.

The first version of the treaty was signed on December 30, 1853. James Gadsden, the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, and Antonio López de Santa Anna, who was Mexico's president, signed it. The U.S. Senate approved it on April 25, 1854, and President Franklin Pierce then sent it to Mexico. Mexico's government approved it on June 8, 1854, making the treaty official. This purchase was the last major land deal that shaped the contiguous United States. Cities like Tucson and Yuma are on land bought in the Gadsden Purchase.

Mexico's government, led by Santa Anna, needed money. So, they agreed to sell the land for $10 million. This was a lot of money back then! Some historians believe Santa Anna thought it was better to sell the land and get paid than to risk the U.S. just taking it without payment, especially after the Mexican–American War (1846–1848).

Contents

- Why the U.S. Wanted the Land: Building a Southern Railroad

- Solving Border Problems: The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

- Final Negotiations and Approval of the Treaty

- Life in the Region After 1854

- Population in the Gadsden Purchase Area

- Was the Gadsden Purchase a Good Deal?

- The Gadsden Purchase in Pop Culture

- See also

- Images for kids

Why the U.S. Wanted the Land: Building a Southern Railroad

As railroads became more important, business leaders in the southern U.S. saw a chance to boost trade. They wanted a railroad that would connect the South to the Pacific Coast. However, the existing border with Mexico had many mountains. These mountains made it hard to build a direct railroad route.

Southern leaders realized that to avoid the mountains, a railroad might need to go south into Mexican territory. This would allow for a flatter path to the Pacific. President Pierce and his Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, saw this as a good opportunity. They wanted to get land for the railroad and possibly more territory from northern Mexico.

At the time, there was a big debate in the U.S. about slavery. When new land was acquired, people argued whether it would be slave or free territory. This debate slowed down the building of the southern transcontinental railroad until the 1880s. However, the land was eventually used for the railroad as planned.

Early Ideas for a Southern Railroad Route

In 1845, a man named Asa Whitney proposed building a transcontinental railroad. Later that year, a meeting in Memphis discussed the idea. Many important people attended, and James Gadsden was very influential. He pushed for a southern route for the railroad. This route would start in Texas and end in San Diego or Mazatlán, Mexico. Southerners hoped this would bring wealth to their region and help expand their influence in the West.

After the Mexican–American War ended in 1848, interest in southern railroads grew. Surveys showed that a railroad from El Paso or western Arkansas to San Diego was possible. People like J. D. B. DeBow and James Gadsden promoted the benefits of this railroad in the South.

Gadsden was the president of the South Carolina Canal and Railroad Company. He wanted to connect all southern railroads into one big network. He worried that new railroads in the North were shifting trade away from the South. He also saw his hometown, Charleston, losing its importance as a seaport. Many southern businesses also feared that a northern railroad route would prevent the South from trading with Asia.

In 1849, southern leaders held another meeting in Memphis to discuss railroads. They strongly supported a route starting in Memphis and connecting to a line from El Paso to San Diego. The only disagreement was about how to pay for it. Some preferred private funding, while others thought the government should provide land grants to railroad builders.

Stephen Douglas and Land Grants

The Compromise of 1850 helped create the Utah Territory and the New Mexico Territory. This made it easier to plan a southern railroad route to the West Coast. Now, all the land for the railroad was organized, which allowed for federal land grants to help pay for it. President Millard Fillmore set a precedent by signing a bill that allowed a railroad from Mobile to Chicago to be funded by federal land grants. These grants would first go to the state or territory, then to private companies.

However, by 1850, most of the South was not very interested in building a transcontinental railroad. The southern economy relied on cotton exports, and existing transportation worked for their plantation system. There wasn't much local trade within the South. Many believed it was better to invest money in more slaves and land than in railroads or canals.

Solving Border Problems: The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Mexican–American War ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. But this treaty left some important issues unresolved between the U.S. and Mexico. These included who owned the Mesilla Valley, how to protect Mexico from Native American raids, and transit rights across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

The Mesilla Valley Dispute

The treaty called for a joint commission to decide the final border. The treaty used an old map, but surveys showed that El Paso was in a different location than the map showed. This led to a dispute over a few thousand square miles of land, including the Mesilla Valley. This valley was very important because it was flat and perfect for building a southern transcontinental railroad.

The U.S. negotiator, John Russell Bartlett, initially agreed to let Mexico keep the Mesilla Valley. In return, the border would shift to include the Santa Rita Mountains, which were thought to have valuable copper, silver, and gold. However, southern U.S. leaders opposed this because it affected the railroad route. They stopped funding for surveying the disputed land. Mexico insisted that the original agreement was valid and prepared to send troops.

Native American Raids and Border Protection

Article XI of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo stated that the U.S. would protect Mexicans from raids by Comanche and Apache tribes crossing the border. At the time, U.S. Secretary of State James Buchanan believed the U.S. could keep this promise. However, it was very difficult. Native American warriors had been fighting intruders for centuries. Even with many U.S. soldiers along the border, they couldn't stop the quick attacks.

Mexico became frustrated because the U.S. couldn't stop the raids. They demanded money for the damage caused to Mexican citizens. The U.S. argued that the treaty didn't require them to pay compensation. Mexico claimed $40 million in damages but offered to let the U.S. pay $25 million to remove this part of the treaty. President Fillmore offered $10 million less.

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec Transit Rights

During the treaty negotiations, the U.S. failed to get transit rights across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in southern Mexico. This narrow strip of land, about 125-mile-wide (201 km), was a good place to build a railroad connecting the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean.

In 1842, Mexican President Santa Anna had sold the rights to build a railroad or canal there. An American businessman, Peter A. Hargous, later bought these rights. He wanted support from both the Mexican and American governments. The U.S. wanted to protect Hargous's rights and ensure easy transit.

The U.S. and the United Kingdom signed the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty in 1850, which said any such canal would be neutral. Mexican negotiators refused to accept this treaty because it would limit Mexico's power. Hargous continued to try to build the railroad, even after Mexico canceled his contract. He asked the U.S. government to help, but President Fillmore refused.

Final Negotiations and Approval of the Treaty

The new U.S. President, Franklin Pierce, took office in March 1853. He and his team were very interested in expanding the U.S. territory. Pierce appointed James Gadsden as ambassador to Mexico. Gadsden's main job was to negotiate with Mexico to buy more land. He was specifically told to get the Mesilla Valley for the railroad. He also had to convince Mexico that the U.S. was doing its best about the Native American raids and get Mexico's help for a canal or railroad across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

Gadsden and Santa Anna Meet

Mexico was facing political and money problems. Santa Anna had just returned to power and needed money to rebuild the Mexican Army. He was willing to deal with the U.S. because of this. He initially didn't want to sell more land and insisted on payment for the Native American raids. However, he agreed to let an international group decide on the raid payments. Gadsden realized Santa Anna needed money and told his superiors.

President Pierce and his Secretary of State, William L. Marcy, gave Gadsden new instructions. Gadsden was allowed to buy one of six different land parcels, each with a set price. The price would also cover all Native American raid damages, freeing the U.S. from future obligations. For example, $15 million would buy about 38,000 square miles (98,000 km2) of desert land needed for the railroad.

Gadsden's way of dealing with Santa Anna was not always friendly. He suggested that northern Mexican states would soon break away from Mexico anyway, so Santa Anna might as well sell them now. Mexico didn't want to sell a huge amount of land. Santa Anna was also worried about an American named William Walker who tried to take over Baja California. Santa Anna needed to get as much money as possible for the smallest amount of land. When the United Kingdom refused to help Mexico in the talks, Santa Anna agreed to the $15 million deal for the smaller land area.

Santa Anna and James Gadsden signed the treaty on December 30, 1853. Then, it went to the U.S. Senate for approval.

The Treaty's Approval

President Pierce and his team discussed the treaty in January 1854. Even though Pierce was a bit disappointed with the amount of land, he signed it and sent it to the Senate on February 10. Gadsden thought that northern Senators might block the treaty to prevent the South from getting its railroad.

The treaty needed a two-thirds vote to pass in the U.S. Senate. It faced strong opposition. Senators who were against slavery didn't want the U.S. to get more land where slavery might expand. Some senators also didn't want to give Santa Anna money.

On April 17, the Senate voted 27 to 18 for the treaty, but this was three votes short of the two-thirds needed. After this, Secretary Davis and southern Senators pushed Pierce to add more parts to the treaty. These changes included:

- Protecting the Sloo grant (a previous land deal for a canal).

- Requiring Mexico to fully protect the building of the canal.

- Allowing the U.S. to step in with its military if needed.

- Reducing the land to be bought by 9,000 square miles (23,000 km2) to its final size of 29,670-square-mile (76,800 km2).

- Lowering the price from $15 million to $10 million.

This new version of the treaty passed the U.S. Senate on April 25, 1854, with a vote of 33 to 12. The smaller land area was a compromise to satisfy northern senators who opposed adding more slave territory. Gadsden took the updated treaty back to Santa Anna, who accepted the changes. The treaty officially started on June 30, 1854.

Even though the land was now available for a southern railroad, the issue became too tied to the debate over slavery. This meant it didn't get federal funding for a long time. Railroad building sped up in the North but slowed down in the South.

Life in the Region After 1854

Army Control and Early Settlements

After the Gadsden Purchase, people living in the area became full U.S. citizens. They slowly became part of American life over the next 50 years. The biggest danger to settlers was raids by Apache Native Americans. The U.S. Army took control of the land in 1854, but it wasn't until 1856 that troops were stationed there. In 1857, Fort Buchanan was built to protect the area.

This new stability brought miners and ranchers to the region. By the late 1850s, mining camps and military posts changed the Arizona countryside. They also created new trade routes with Sonora, Mexico.

The Civil War and Arizona's Territory

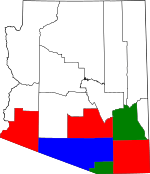

During the American Civil War in 1861, the Confederate States of America created the Confederate Territory of Arizona. This new territory mainly included the areas from the Gadsden Purchase. In 1863, the Union created its own Arizona Territory from the western part of the New Mexico Territory. This new American Arizona Territory also included most of the Gadsden Purchase lands. Arizona became a U.S. state on February 14, 1912. It was the last area of the Lower 48 States to become a state.

Social and Economic Changes

After the Gadsden Purchase, many of the important families in southern Arizona were Mexican American. This changed when the railroad arrived in the 1880s. When silver mines opened, they hired educated Americans to manage them. The workforce became a mix of Europeans, Americans, Mexicans, and Native Americans.

From the late 1840s to the 1870s, Texas cattle ranchers moved their herds through southern Arizona. They were impressed by the good grazing land in the Gadsden Purchase area. Later in the century, they moved their herds there and started the cattle ranching industry. They brought their ranching methods, but also problems like cattle rustling and diseases. These issues led to new laws and groups to solve them.

In the 1860s, fighting between the Apaches and Americans was at its peak. Almost constant warfare happened near the Mexican border until 1886. The area also saw growing towns, smuggling, and cattle theft. Bandits often used the U.S.-Mexico border to raid one side and hide on the other.

There was also tension between the rural residents (often Democrats from the South) and town residents and business owners (often Republicans from the Northeast). This tension led to conflicts like the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona.

The Gadsden Purchase also divided the Tohono Oʼodham Nation and their traditional lands with the new border. This made it hard for them to travel and move goods, which affected their culture and economy.

Railroad Development in the Region

In 1846, James Gadsden suggested building a transcontinental railroad from Charleston, South Carolina, to San Diego, California. Surveys showed this southern route was possible. However, disagreements over slavery and the Civil War delayed construction.

The Southern Pacific Railroad reached Yuma, Arizona, in 1877. It arrived in Tucson, Arizona in 1880, Deming, New Mexico in December 1880, and El Paso in May 1881. This was the first railroad across the Gadsden Purchase.

At the same time, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad was building across New Mexico. It met the Southern Pacific in Deming, New Mexico, on March 7, 1881. This completed the second transcontinental railroad in the U.S. (The first was completed in Utah in 1869). The Santa Fe then built a line southwest into Mexico. The Southern Pacific continued building east from El Paso, completing its own southern transcontinental route, the Sunset Route, in 1883.

These railroads led to a mining boom in the 1880s in places like Tombstone, Arizona, Bisbee, Arizona, and Santa Rita, New Mexico. These areas became major copper producers. Another railroad, the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad, was built across the Gadsden Purchase to El Paso by 1905. It later connected to another line, forming the Golden State Route.

Today, the Southern Pacific (now part of Union Pacific Railroad) and the Santa Fe (now part of BNSF) are among the busiest rail lines in the United States. The rugged land north of the Gila River confirmed that buying the Gadsden Purchase was a smart move for building a southern transcontinental railroad.

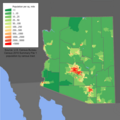

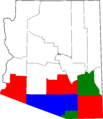

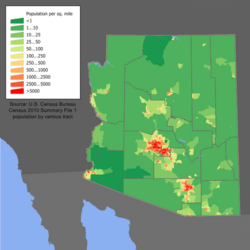

Population in the Gadsden Purchase Area

Arizona Counties in the Purchase

Most of the population in the Gadsden Purchase area of Arizona lives in six counties. While some parts of these counties extend north of the purchase line, those areas are not as populated. Tucson is the largest city in the Gadsden Purchase.

| County | Seat | Pop. | Area (mi2) | Area (km2) |  |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cochise | Bisbee | 131,346 | 6,219 | 16,110 | ||

| Graham | Safford | 37,220 | 4,641 | 12,020 | ||

| Pima | Tucson | 980,263 | 9,189 | 23,800 | ||

| Pinal | Florence | 375,770 | 5,374 | 13,920 | ||

| Santa Cruz | Nogales | 47,420 | 1,238 | 3,210 | ||

| Yuma | Yuma | 195,751 | 5,519 | 14,290 | ||

| Total | 1,767,770 | 32,180 | 83,350 |

The northernmost point of the Gadsden Purchase is near Goodyear, Arizona, about 30 miles (48 km) southwest of Phoenix, Arizona.

New Mexico Communities in the Purchase

Sunland Park, a suburb of El Paso, Texas, is the largest community in New Mexico that is part of the Gadsden Purchase. Lordsburg, New Mexico was in the disputed area before the purchase. The Gadsden Purchase helped resolve these border disagreements and transferred this land to the U.S.

Was the Gadsden Purchase a Good Deal?

In 1969, geologist Harold L. James said that even with all the confusion, the Gadsden Purchase was "extremely valuable." He believed it paid for itself with its mineral and agricultural resources.

However, economist David R. Barker in 2009 suggested it might not have been profitable for the U.S. government. He noted that the region doesn't bring in much tax money. Also, the U.S. spent a lot of money in the 1800s defending the territory from Native American tribes, which wouldn't have been necessary without the purchase.

The Gadsden Purchase in Pop Culture

- The film Conquest of Cochise (1953) uses the Gadsden Purchase as a background for its story about Mexicans and Native Americans in the region.

- The United States Post Office Department released a postage stamp on December 30, 1953, to celebrate 100 years since the Gadsden Purchase.

- In 2012, the Gadsden Purchase was featured on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon.

- A character in the 2021 novel Billy Summers by Stephen King is named "Gadsden Drake" after the Gadsden Purchase.

See also

In Spanish: Venta de La Mesilla para niños

In Spanish: Venta de La Mesilla para niños

Images for kids

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |