Mississippi River Delta facts for kids

The Mississippi River Delta is where the mighty Mississippi River meets the Gulf of Mexico in Louisiana, in the southeastern United States. This amazing area of land, called a river delta, covers about 3 million acres (12,000 square kilometers). It stretches along Louisiana's coast, from Vermilion Bay in the west to the Chandeleur Islands in the east.

The Mississippi River Delta is a huge part of the Gulf of Mexico and Louisiana's coastal plain. It is one of the largest wetland areas in the United States. In fact, it's the seventh-largest river delta on Earth! This important region has over 2.7 million acres (11,000 square kilometers) of coastal wetlands. It also holds 37% of the estuarine marsh in the connected U.S. The delta is the nation's biggest drainage basin. It sends about 41% of the water from the contiguous United States into the Gulf of Mexico. This happens at an average rate of 470,000 cubic feet (13,300 cubic meters) per second.

Contents

How the Mississippi Delta Formed and Grew

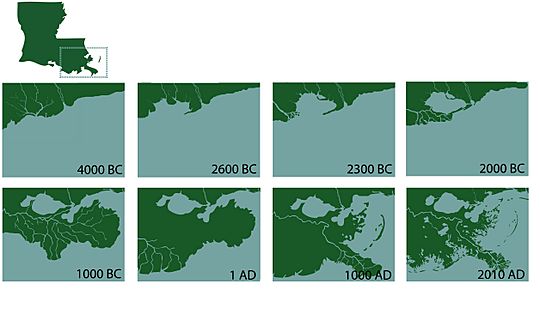

The Mississippi River Delta we see today began to form about 4,500 years ago. The Mississippi River carried sand, clay, and silt. It dropped these materials along its banks and in nearby areas. This created new land over time. The delta's unique "birdfoot" shape shows how much the river controls its environment.

Before the 1930s, when many levees were built, the river often changed its path. About every 1,000 to 1,500 years, the river would find a shorter way to the Gulf of Mexico. This natural process is called avulsion, or delta-switching. These changes in the river's course helped create the Louisiana coastline. They also formed over 4 million acres (16,000 square kilometers) of coastal wetlands.

When the river changed course, the flow of freshwater and sediment also changed. This led to periods where new land was built in some areas. At the same time, other areas experienced land loss. This natural cycle of change created the many different landscapes of the Mississippi River Delta.

The Atchafalaya River is the largest branch of the Mississippi River. It also plays a big role in building new land within the delta. This river branch formed about 500 years ago. The Atchafalaya and Wax Lake deltas started to appear in the mid-1900s.

People have lived in the delta region for a long time. They have always faced the river's natural floods and changes. As more people moved in and built homes, they wanted to protect themselves from the river. Starting in the 20th century, new technology allowed people to change the river a lot. These changes helped protect many people and boosted the economy. However, they also had big negative effects on the delta downstream.

The Delta's Ancient History

|

|

Salé-Cypremort | 4,600 years ago |

|

|

Cocodrie | 4,600–3,500 years ago |

|

|

Teche | 3,500–2,800 years ago |

|

|

St. Bernard | 2,800–1,000 years ago |

|

|

Lafourche | 1,000–300 years ago |

|

|

Plaquemine | 750–500 years ago |

|

|

Balize | 550 years ago |

The Mississippi River Delta started forming a very long time ago. This was during the late Cretaceous Period, about 100 million years ago. At that time, a large dip in the land, called the Mississippi embayment, began to collect sediment. This process helped build the land for the future delta.

During the Holocene Epoch, about 7,500 to 8,000 years ago, the modern delta plain really began to grow. This happened because sea levels stopped rising so quickly. Also, the river naturally shifted its course every 1,000 to 1,500 years.

This natural process is called the "delta cycle." The river drops sediment at its mouth, building new land. Then, it eventually finds a shorter path to the sea and leaves its old course. After the river changes direction, the old delta area can lose land. This happens due to the land sinking, erosion of the marsh shoreline, and sand moving around. The delta cycle includes both land loss and land gain. This process created the bays, bayous, coastal wetlands, and barrier islands that make up Louisiana's coastline.

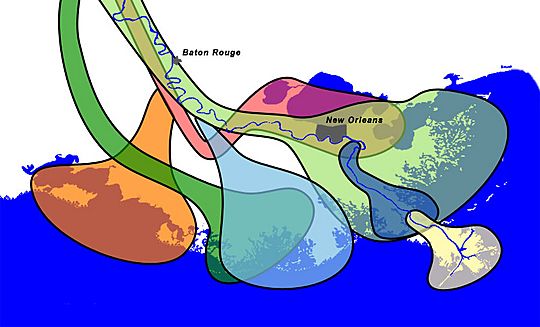

The main delta cycle of the Mississippi River began over 7,000 years ago. It formed six large delta areas. These areas are made up of smaller parts called delta lobes. These lobes include the basins and other natural landscapes of the coast.

Here are the six main delta areas:

- The Maringouin delta formed 7,500 to 5,500 years ago.

- The Teche delta formed 5,500 to 3,500 years ago.

- The St. Bernard delta formed 4,000 to 2,000 years ago. The river moved east of present-day New Orleans.

- The Lafourche delta formed 2,500 to 500 years ago. The river moved west of present-day New Orleans.

- The Plaquemines-Balize delta, also known as the Bird's Foot Delta, formed over the past 1,500 years. It is between the St. Bernard and Lafourche deltas.

- The Atchafalaya and Wax Lake Outlet deltas began forming 500 years ago. They became more noticeable in the mid-20th century. The Wax Lake Outlet channel was created in 1942 to help reduce water levels at Morgan City.

People, Economy, and Culture of the Delta

Delta History and Early Settlements

The history and culture of the Mississippi River Delta are very special. Spanish explorer Alvarez de Pineda found the mouth of the Mississippi River in 1519. Later, Robert Cavelier de La Salle claimed the area for France in 1682. The region became important for trade and safety due to its location.

In 1699, the French built a simple fort at La Balize. This was to control passage on the Mississippi River. By 1721, they had built a lighthouse-like structure. The French word for 'seamark' is la balise, which gave the settlement its name. The village was built in marshy areas, so it was often damaged by hurricanes. Ships also had to deal with changing tides, currents, and mudflats. From 1700 to 1888, the main shipping channel changed four times because of shifting sandbars and storms.

In 1803, the United States bought Louisiana from France in the Louisiana Purchase. New Orleans and the river's mouth became even more important for trade and farming. The rich soil from the Mississippi River made the delta perfect for growing sugar cane, cotton, and indigo. These crops were important before the Civil War. Many of these resources are still important to the delta today.

After the Civil War, trade on the Mississippi River grew even more. In the 1870s, former delta swamplands were turned into rich farmland using levees. Timber companies harvested valuable forests. Farmers followed, using the new agricultural land. More railroads were built, replacing steamboats for transporting goods.

When the Panama Canal opened in 1914, the Mississippi River Delta became an even more vital transportation route. Fishing also grew. The discovery of large oil and gas deposits brought more economic and environmental changes. Despite these changes, the delta still has strong cultural traditions today.

Diverse People of the Delta

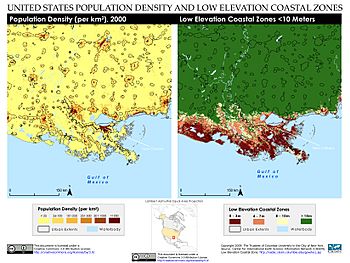

More than two million people call the Mississippi River Delta home. Its location at the mouth of the Mississippi River made it a gateway to the United States. This led to many different nationalities settling there over time. This mix created the region's diverse population.

In the 18th century, Louisiana's first colonists were French. Soon, Spanish and Acadian settlers joined them. Later, in the 19th century, other European groups arrived, including Germans, Sicilians, and Irish. There were also Africans, West Indians, and Native Americans. This blend of groups created the special culture found in the Mississippi River Delta, which includes the Acadiana cultural region.

Two unique groups are the Creoles and the Cajuns. Generally, Creole refers to a person born in Louisiana with French and/or Spanish parents. Over time, Creoles also included people of African, European, and Native American backgrounds. During colonial times, many Creoles of diverse backgrounds were free. They often received an education and owned businesses and property.

The Cajuns are another ethnic group in southern Louisiana. They are mainly descendants of Acadian settlers. These Acadians were forced to leave Nova Scotia by the British after the French and Indian War. The Cajuns have married people from many backgrounds. They have greatly influenced Louisiana's culture. Both Creole and Cajun cultures are strong influences in the Mississippi River Delta. They shape food, music, and art. They also keep the unique identities alive in the southernmost parts of the region. Both cultures speak a form of French, but they are distinct dialects.

Delta Culture and Traditions

From 1910 to 1920, New Orleans became the birthplace of jazz music. It has continued to be a home for new musicians and musical styles. Music is deeply connected to the region's unique culture and diverse heritage. Jazz and blues music started here because the delta's location brought many cultural influences. These included blues and bluegrass from upriver, and African and Latin folk music from the Caribbean islands. Today, the delta is still known for jazz, funk, and zydeco sounds. It remains an important cultural center, drawing thousands of visitors each year.

The region is also famous for its unique food. Cajun food uses ingredients found in the delta. Spices, shellfish, and grains from the delta's rich environment make these dishes flavorful. Cajun cooking attracts many tourists each year. Its recipes have also become popular around the world.

The Delta Today: Economy and Ecology

The Mississippi River Delta offers many natural habitats and resources. These benefit Louisiana, the coastal region, and the entire nation. The coastal wetlands have diverse landscapes. They connect many different habitats to both land and water.

Louisiana's wetlands are some of the nation's most important natural assets. They include natural levees, barrier islands, forests, swamps, and marshes (fresh, brackish, and salty). This region is home to complex ecosystems. These are vital for its unique and vibrant nature. Besides environmental benefits, the delta also provides many economic resources. These vital resources are always at risk due to ongoing land loss.

Delta Economy and Industries

The Mississippi River Delta has a strong economy. It relies heavily on tourism and activities like fishing, hunting, and wildlife watching. Commercial fishing, oil, gas, and shipping industries are also very important. Here are some major industries:

- Oil and gas: About one-sixth of Louisiana's workers are in the oil and gas industry. Louisiana is a key gateway for the nation's oil and gas supply. In 2013, it was second only to Texas in refinery capacity. Port Fourchon services 90% of the offshore oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico. It provides 16-18% of the country's oil supply. Natural gas is also a strong industry. Louisiana produces over one-tenth of US natural gas supplies. It has almost 50,000 miles (80,000 km) of pipelines. Gas is delivered to the entire nation from the Gulf of Mexico.

- Shipping and ports: The delta's ports are some of the busiest in the nation. Being at the mouth of the Mississippi River makes Louisiana's ports major entry points to the rest of the United States. Five of the U.S.'s largest ports are in Louisiana, including Baton Rouge and New Orleans. The Port of South Louisiana is the largest port in the U.S. by tonnage. It exports over 52 million tons a year, mostly farm products. Louisiana's river ports provide about 270,000 jobs. They bring over $32.9 billion annually to the state's economy. The Mississippi River moves about 500 million tons of cargo each year. This includes over 60% of the nation's grain exports. Louisiana's ports are vital for U.S. shipping. They connect to countries like China, Japan, and Mexico.

- Fisheries: Both commercial and recreational Fisheries are important for Louisiana's coast. Fishing provides a way of life for many people. Louisiana has the second largest commercial fishery in the United States by weight, after Alaska. The delta has seven of the top 50 seafood landing ports in the U.S. Three of these are in the top six nationwide. The Gulf region provides 33% of the nation's seafood harvest. Commercial fishing is a $2.4 billion industry in the Gulf of Mexico. About 75% of the fish landed come through Louisiana ports.

- Tourism: Louisiana offers many opportunities for tourists to enjoy the delta. These include eco-tourism activities like fishing, hunting, and swamp tours. Traditional tourism includes eating at Gulf Coast restaurants with local seafood. Thousands of tourists also come each year for the region's unique cultural events.

The five Gulf Coast states together generate about $34 billion annually from tourism. Wildlife tourism is a key part of this. It brings in over $19 billion in annual spending by tourists. It also generates over $5 billion in federal, state, and local tax revenue.

Delta Ecology and Wildlife

The Mississippi River Delta has a very diverse ecological landscape. It includes many wildlife habitats and types of plants. The delta's coastal landscape is rich in resources. It contains some of the most unique areas in the United States. Besides providing homes for wildlife, the delta's wetlands, marshes, and barrier islands also protect coastal residents from storm surge and flooding.

- Landscapes – Here are some of the different landscapes in the Mississippi River Delta:

- Fresh, intermediate, brackish, and saline marshlands make up over 3 million acres (12,000 square kilometers) of Louisiana's coastline. This is 13% of the state's total land.

- Barrier islands are home to many birds. They provide the first line of protection for Louisiana residents from hurricane storm surge.

- Swamps are forested wetlands. The biggest swamp in the delta is 1 million acres (4,000 square kilometers) in the Atchafalaya Basin.

- Bottomland hardwood forests and maritime forests.

- Beaches.

- Coastal flatwoods.

- Southwest Louisiana's ecosystem once had 2.5 million acres (10,000 square kilometers) of coastal tallgrass prairie habitat (Western Gulf coastal grasslands). Much of this has been replaced by cattle ranching and farming.

- Wildlife – The delta's varied landscapes provide habitats for hundreds of species of animals, birds, and other wildlife. Many of these species are unique to the Mississippi River Delta. They rely on the mix of wetland, marsh, and forest ecosystems.

Many mammals live in the delta's forests, swamps, and estuaries. These include Louisiana black bears, bottlenose dolphins, minks, beavers, armadillos, foxes, coyotes, and bobcats. The region also has invasive mammals like nutria and feral hogs. These animals can harm native ecosystems and species.

The delta is a vital stopping point along the Mississippi Flyway. This flyway stretches from southern Ontario to the mouth of the Mississippi River. It is one of the longest migration routes in the Western Hemisphere. About 460 bird species have been recorded in Louisiana. 90% (300 species) are found in the coastal wetlands. Many diverse and rare species call Louisiana home, such as indigo buntings, scarlet tanagers, yellow-crowned night herons, and bald eagles. Great egrets, glossy ibises, roseate spoonbills, wintering hummingbirds, birds of prey, and wood storks are also found here.

- Fish – Delta wetlands provide fish habitats. They act as nurseries for many important young fish species. Ninety-seven percent of the Gulf's commercial fish and shellfish species spend part of their lives in coastal wetlands, like those in Louisiana. Examples of fish found in the delta include speckled trout, redfish, flounder, blue crabs, shrimp, catfish, and bass.

- Endangered and threatened species – The Mississippi River Delta is home to several species listed as endangered or threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Delta National Wildlife Refuge. Ongoing land loss and wetland erosion seriously threaten these species and their habitats. These include the:

- Piping plover (Charadrius melodus)

- Kemp's Ridley Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii)

- Louisiana black bear

Threats to the Mississippi River Delta

Throughout its long history, the Mississippi River Delta naturally grew and shrank. This was due to sediment from the river. However, in recent times, land loss has happened much faster than the river can build new land. This is due to several factors. Some causes are natural, like hurricanes and climate change. But the delta also suffers from a lack of sediment. This is caused by dams, levee systems, navigation canals, and other human-made structures in the Mississippi basin.

These structures have harmed the river's natural land-building power. Many of them slow or stop the river's flow into certain areas. This increases salt-water intrusion from the Gulf of Mexico into freshwater wetlands. The saltwater weakens these freshwater ecosystems. This makes them more vulnerable to destruction by hurricanes and unable to withstand heavy storm surge. To understand these problems better, the LSU Center for River Studies built a large physical model of the Lower Mississippi River Delta. It simulates water flow and sediment movement.

Land Sinking (Subsidence)

When the river doesn't bring new sediment, the land in the Mississippi River Delta sinks faster than in other parts of the U.S. This sinking is called subsidence. Some researchers suggest that taking out fluids by the gas and oil industry might make subsidence worse.

Hurricanes and Storms

Coastal wetlands and barrier islands are the first protection for Louisiana communities from hurricanes and storm surge. But as these landscapes weaken, they become more vulnerable to strong winds and flooding. For example, after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, about 200 square miles (520 square kilometers) of wetlands turned into open water. This showed permanent wetland loss.

Rising Sea Levels

A combination of land sinking, hurricanes, storms, and sea level rise leads to more marsh and wetland loss. Climate change also affects the strength of the coastline. As global sea levels rise, areas in the delta that are sinking may permanently flood. They could become open water. Also, the lack of sediment in these flooded areas makes the effects of sea level rise worse.

Levees and Their Impact

Levees were mainly built along the river to prevent floods. They also helped stabilize the shoreline for easier navigation. Many levees were built after the big river flood of 1927. The Flood Control Act of 1928 authorized a large project. This project built a system of levees, floodways, and channel improvements. It aimed to protect residents from river overflows. This system has been very successful in preventing flood damage. It has saved the region billions in potential damage.

However, this success has come at a cost for the delta's natural landscapes. The levees cut off the connection between the river and the surrounding wetlands. The freshwater and sediment carried by the river are needed for land to grow in the delta. But the levees block this process. They stop sediment from being deposited in most areas of the delta.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, oil and gas exploration grew in the Gulf of Mexico and along Louisiana's coast. Companies dug canals to create deeper channels for ships and to lay pipelines. Over time, 10 major navigation canals and more than 9,300 miles (15,000 km) of pipelines were placed throughout coastal Louisiana. These serve about 50,000 oil and gas production facilities.

Digging these canals directly caused wetlands to be lost. According to a government report, these actions caused 30 to 59% of wetland loss in Louisiana from 1956 to 1978. Dredging also causes more serious long-term damage. It disrupts the natural water flow of the region. These canals and pipelines are vital for the nation's resources. However, they have increased erosion and damage to the delta. They create open water areas that allow saltwater to enter freshwater wetlands. This harms water quality and changes the wetlands' water flow. It reduces the nutrients and sediments needed for these areas to survive.

The Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MRGO) is an example of wetland loss caused by a navigation channel. It was built in the 1960s. It connected the Gulf of Mexico to the Port of New Orleans. It led to the destruction of 27,000 acres (110 square kilometers) of wetlands. It also allowed saltwater to enter freshwater ecosystems. It is also believed to have acted like a "funnel" for Hurricane Katrina storm surge. This contributed to a big increase in flooding in St. Bernard and the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans.

Upriver Dams

Dams and reservoirs in the upper part of the river basin have reduced the amount of sediment in the lower Mississippi River. These structures are mainly on the sediment-rich Missouri River. They block and trap the river's land-building sediment. This cuts off the replenishing nutrients and minerals needed for the delta's unique ecosystems to be stable and survive. Since the 1950s, these structures have cut the sediment load by almost half.

Restoring the Mississippi River Delta

The Mississippi River took thousands of years to build its delta. But land loss is happening much faster. Over the past decade, many steps have been taken to make coastal Louisiana stronger. Research has been done to find the best restoration projects. These projects aim to stop further land loss and rebuild the delta. Studies have estimated that without new sediment, 10,000 to 13,000 square kilometers (3,900 to 5,000 sq mi) of the delta could be underwater by 2100. This shows a clear need for focused restoration efforts.

Louisiana Coastal Area (LCA) Projects

These projects are part of the Water Resources Development Act of 2007 (WRDA 2007). This act allows the Army Corps of Engineers to work on flood control, navigation, and environmental projects. Some important LCA Projects include:

- MRGO Ecosystem Restoration Plan: After Hurricane Katrina, the damage linked to the Mississippi River–Gulf Outlet Canal led the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to create a restoration plan. This plan included closing the channel. The plan aimed to rebuild habitats through marsh, swamp, and oyster reef restorations. It also focused on wetland ecosystem restorations using freshwater diversions and other structures to strengthen the coastline.

- River diversions: These projects involve a lot of research. They are carefully designed to send sediment to nearby marshes or increase freshwater flow. Sediment diversions can be built and operated to maximize the sediment sent to wetlands that need it. These diversions can form new land and strengthen existing wetlands. Examples in the delta include the West Bay and Mid-Barataria diversions. River diversions are a way to increase sedimentation.

- Redirecting sediment: The Atchafalaya River Basin is a river swamp with a lot of extra sediment. This basin has the largest area of naturally built new marsh in the state. It has been suggested that sediment from the Atchafalaya River could be used to help the Louisiana coast. Delta growth in this basin happened from 1952 to 1962, and again during the 1973 Mississippi River flood. The growth from 1973 is known as the Wax Lake Outlet. This area has grown each year since 1973 to its current size of 11.3 square miles (29 square kilometers).

2012 Louisiana Coastal Master Plan

The state's Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) brought together scientists and engineers. They created a $50-billion, 50-year plan to save Louisiana's coast. The plan was approved in May 2012. It outlines 109 projects to bring long-term benefits to coastal communities and ecosystems. These projects include restoring water flow, diverting sediment, restoring barrier islands, and creating new marshes. Some projects are already happening, but many still need more approval and funding.

- River Diversions and Community Concerns: Some river diversion projects aim to reconnect the river to the delta. They are designed to copy natural processes of sediment spread and delta growth. An example is the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion. This project is in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. It is seen as a critical restoration project. It aims to address land loss in the Barataria Basin and strengthen wetlands. However, this project has faced concerns from local communities. Residents of Ironton, a historic African American community near the diversion, worry about how the freshwater from the Mississippi River will affect commercial fishing in the area. They are also concerned about increased water levels in the wetlands during storms. People who have lived on the land for generations are also cautious. They point to past projects, like the Bohemia Spillway, where they felt their communities were not treated fairly. This history has led to a lack of trust in some scientific plans.

Bohemia Spillway History

In 1926, the Bohemia Spillway was proposed as an experiment. It aimed to help levees control high water. Eleven miles (18 km) of levee were removed in this area, which was newly purchased land downriver from New Orleans. This second outlet for the Mississippi River helped reduce flooding upstream during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. However, the way this land was acquired has a controversial history. Small Black and immigrant communities living there at the time were forced to move. Newspaper reports claimed residents were fully paid for their land, but later legal cases showed this was not true. It was also revealed that this land had generated $43 million in oil and gas revenues by the 1980s. This made residents believe the true reason for the Bohemia Spillway project was to get oil, not just for science. This history of unfairness has led to distrust in scientists and, by extension, in projects like the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion.

RESTORE Act

The Resources and Ecosystems Sustainability, Tourist Opportunities and Revived Economies of the Gulf Coast States Act (RESTORE Act) became law on July 7, 2012. This law followed the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010. It ensures that 80 percent of the civil Clean Water Act fines paid by BP and other responsible parties go to the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council and five Gulf Coast states. This money is used for environmental and economic restoration.

See also

In Spanish: Delta del río Misisipi para niños

In Spanish: Delta del río Misisipi para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |