Louisiana Creole people facts for kids

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Indeterminable | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, Alabama, California | |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Spanish and Louisiana Creole (Kouri-Vini) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Cajuns, Creoles of color, Isleños, Québécois, Haitians, Saint Dominicans, Alabama Creoles

Peoples in Louisiana Métis Acadians French Americans French-Canadian Americans Cajuns Native Americans Caribbean Americans Spanish Americans Portuguese Americans Afro Latino Cuban Americans Dominican Americans Stateside Puerto Ricans Canarian Americans Mexican Americans Italian Americans German Americans Irish Americans |

Louisiana Creoles are people whose families have lived in Louisiana since it was a French or Spanish colony. They are an ethnic group with roots mainly from French, West African, Spanish, and Native American people. Louisiana Creoles share a special culture. This includes speaking French, Spanish, and Louisiana Creole languages. Most of them also practice Catholicism.

The word Créole was first used by French settlers. It helped them tell apart people born in Louisiana from those born somewhere else. It meant people born in the "New World" (America) were different from those born in Europe or Africa. The word Créole is not about race. People of any background can be Louisiana Creoles.

The term "Creole" became important in Louisiana from the 1700s. After the Louisiana Purchase, it gained a stronger meaning. It especially identified people with a Latin culture. These French-speaking Catholics, whether white or black, had a culture different from the new American settlers.

Many white Creoles in Louisiana have French ancestors. This includes people with roots from Quebec or Acadia. While Cajuns are often seen as different, this was not always true. Many people with Cajun ancestors were once called Creoles. Today, some people identify as only Cajun or only Creole. Others embrace both identities.

Later immigrants in the 1800s also joined the Creole group. These included Irish, Germans, and Italians. Most of these new settlers were Catholic.

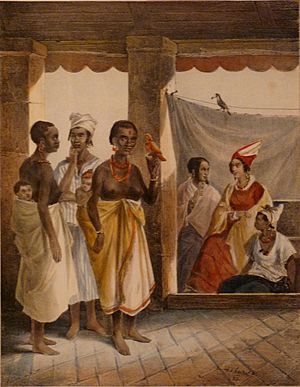

New Orleans has a large group called Creoles of color. These were mostly free people with mixed European, African, and Native American backgrounds. Under Spanish rule, many Creoles of color had more rights and better education. Some of America's first writers and activists of color were Louisiana Creoles. Today, many Creoles of color are part of African-American culture. Others remain a distinct part of the African-American ethnic group.

In the 1900s, the term Creole became more linked to people of color. This happened partly because Anglo-Americans struggled with a culture not based on race. This time is sometimes called the "Americanization of Creoles." It meant accepting the American idea of only "white" or "black" races. At the same time, fewer white people identified as Creole. Many instead started using the Cajun label.

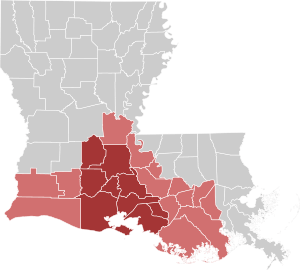

New Orleans' Creole society is well-known. But the Cane River area in northwest Louisiana also has a strong Creole culture. This area was mostly settled by Creoles of color.

Today, most Creoles live near New Orleans or in Acadiana. Louisiana is proudly known as the Creole State.

Contents

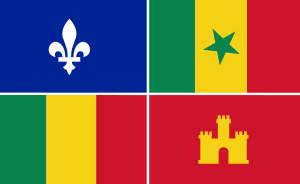

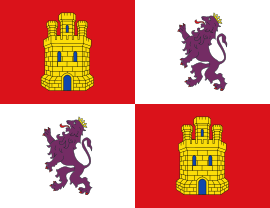

Louisiana Creole Flag

The Louisiana Creole flag uses symbols from four different regions. The top left shows a fleur-de-lis, which stands for France. The top right represents Senegal. The bottom right shows Castile, a region in Spain. The bottom left square represents Mali.

Pete Bergeron created this flag in 1987. He was part of a group called C.R.E.O.L.E. INC. The flag celebrates the many cultures that make up Creole heritage today.

History of Louisiana Creoles

Early French Period

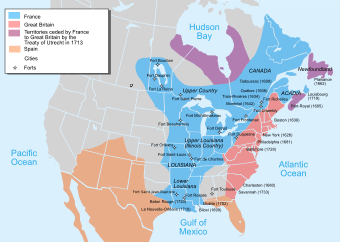

During French and Spanish rule in the 1700s, "Creole" meant people born in the New World. This was different from those born in Europe. Parisian French was the main language in early New Orleans.

Over time, the French language in Louisiana changed. It added local words and slang. This became known as Colonial French. Because Louisiana was far from France, the language grew differently. Both French and Spanish settlers, and their Creole children, spoke it.

Today, a Louisiana Creole is generally someone whose family lived in Louisiana before 1803. That's when the United States bought Louisiana. About 7,000 Europeans moved to Louisiana in the 1700s. This was much fewer than the number of colonists in the Thirteen Colonies.

Life was hard for these early colonists. They faced a new, often dangerous environment. The climate was difficult, and tropical diseases were common. Many died during the long ocean journey or soon after arriving.

Hurricanes, unknown in France, often hit the coast. They destroyed whole villages. The Mississippi Delta had many yellow fever outbreaks. Europeans also brought diseases like malaria and cholera. These spread easily due to mosquitoes and poor sanitation. These problems slowed down settlement. Also, French villages and forts did not always protect against enemies. Attacks by Native Americans were a real danger to isolated settlers.

The Natchez killed 250 colonists in Lower Louisiana. This was in response to French settlers taking their land. Natchez warriors surprised Fort Rosalie, killing many. For the next two years, the French fought back. They forced the Natchez to flee or sent them as slaves to Saint-Domingue (now Haiti).

In the colonial period, men often married later in life. French settlers often married Native American women. As enslaved people arrived, settlers also married African women. These marriages between different groups created a large multiracial Creole population.

Early Settlers and Women

Besides government officials and soldiers, most colonists were young men. They were recruited from French ports or Paris. Some worked as engagés (indentured servants). They had to work in Louisiana for a set time to pay for their travel and living costs. Engagés in Louisiana usually worked for seven years. Their masters provided housing, food, and clothing. They often lived in barns and did hard labor.

To increase the population, the government also sent young Frenchwomen. They were called filles à la cassette (casket girls). They came to the colony to marry soldiers. The king paid for each girl's dowry. This was similar to what happened in Quebec in the 1600s. About 800 filles du roi (daughters of the king) were sent to New France.

French authorities also sent some female criminals to the colony. For example, in 1721, a ship brought nearly 90 women from a Paris prison to Louisiana. Most of these women quickly married men in the colony.

Historian Joan Martin says there is little proof that casket girls were sent to Louisiana. The Ursuline nuns, who supposedly watched over the girls, also deny this story. Martin thinks it's a myth.

French and Native Americans

New France wanted Native Americans to become subjects of the king and Christians. But the distance and few French settlers made this hard. Native Americans were officially seen as subjects of the French king. In reality, they were mostly independent because they were so many. French leaders often had to make deals with them. Native American tribes were vital to the French in Louisiana. They helped colonists survive and traded furs. They also guided expeditions. Their help was key in wars against other tribes and European colonies.

Both peoples influenced each other. French settlers learned Native languages, like Mobilian Jargon. This was a Choctaw-based Creole language used for trade. Native Americans bought European goods like fabric and firearms. They learned French and sometimes adopted Christianity.

French traders and soldiers used canoes and moccasins. Many ate native foods like wild rice and various meats. Colonists often relied on Native Americans for food. Creole cuisine shows these influences. For example, sagamité is a mix of corn, bear fat, and bacon. Today, jambalaya, a word of Seminole origin, is a spicy dish with meat and rice. Sometimes, shamans helped colonists with traditional remedies. They used fir tree gum for wounds and Royal Fern for rattlesnake bites.

Many French colonists admired and feared Native American military power. But others looked down on their culture. Jesuit priests were often shocked by Native American customs. In 1735, mixed-race marriages without official approval were banned in Louisiana. Still, Native Americans did marry French settlers. This created a métis (mixed French Indian) population.

Despite some problems and fights, relations with Native Americans were generally good. French rule involved some wars and enslavement of Native Americans. But most of the time, it was based on talking and making agreements.

Africans in Louisiana

Finding enough workers was a big problem in Louisiana. In 1717, John Law, a French official, decided to bring enslaved Africans to Louisiana. He wanted to grow the plantation economy in Lower Louisiana. The Royal Indies Company controlled the slave trade there. Colonists relied on sub-Saharan African slaves to make their plantations profitable. In the late 1710s, the Atlantic slave trade brought enslaved people to the colony.

Between 1723 and 1769, most enslaved people came from modern-day Senegal, Mali, and Congo. Many were from the Wolof and Bambara groups.

During Spanish control of Louisiana (1770-1803), most enslaved people still came from Congo and Senegambia. But more also came from modern-day Benin. Many were from the Nago people, a Yoruba subgroup.

Africans helped shape Louisiana's Creole society. They brought okra from Africa, which is used in gumbo. The Code Noir (Black Code) said enslaved people should get Christian education. But many practiced animism and mixed it with Christianity. The Code Noir also gave affranchis (freed slaves) full citizenship. It gave them equal rights with other French subjects.

Louisiana's enslaved society created its own Afro-Creole culture. This was seen in religious beliefs and the Louisiana Creole language. Enslaved people brought their cultures, languages, and beliefs. These included spirit and ancestor worship and Roman Catholic Christianity. All these were key parts of Louisiana Voodoo. In the early 1800s, many Saint Dominicans also came to Louisiana. They were both free people of color and enslaved people. They came after the Haitian Revolution in Saint-Domingue. This added to the Voodoo traditions in Louisiana.

Spanish Period

France secretly gave the French colony to Spain in 1762. This happened during the Seven Years' War. Spain was slow to take full control, not doing so until 1769. That year, Spain ended Native American slavery. Also, Spain's policies made it easier for enslaved people to gain freedom. This helped the population of Creoles of color grow, especially in New Orleans. Most of the old buildings in the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) are from the Spanish period. French architects designed them, as there were no Spanish architects in Louisiana. These buildings have a Mediterranean style, also seen in southern France.

Louisiana's multiracial Creole people were greatly influenced by French Catholic culture. This included affranchis (freed slaves), free-born black people, and mixed-race people. They were known as Creoles of color. By the late 1700s, many Creoles of color were educated. They worked as skilled craftspeople and owned businesses and property. Many were born free. Their children often had the same rights as white people under Spanish rule. This included owning property, getting formal education, and serving in the military. Creoles of color had been in the militia for decades. For example, about 80 Creoles of color fought in the Battle of Baton Rouge (1779) in 1779.

During Spanish rule, most Creoles still spoke French. They stayed strongly connected to French culture. However, large Spanish Creole communities in Saint Bernard Parish and Galveztown spoke Spanish. The Malagueños in New Iberia also spoke Spanish. Today, fewer Spanish-speaking Creoles remain. But the Isleños of St. Bernard Parish still keep their traditions from the Canary Islands.

Acadians and Isleños

In 1765, during Spanish rule, thousands of Acadians came to Louisiana. They were from the French colony of Acadia (now in Canada). The British government had expelled them after the French and Indian War. They settled mostly in southwest Louisiana, in the area now called Acadiana. Governor Luis de Unzaga y Amézaga welcomed the Acadians. They became the ancestors of Louisiana's Cajuns.

Spanish Canary Islanders, called Isleños, also moved to Louisiana. They came from the Canary Islands between 1778 and 1783. In 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte of France secretly got Louisiana back from Spain. This deal was kept secret for two years.

Louisiana Purchase and New Arrivals

Spain gave Louisiana back to France in 1800. But it stayed under Spanish control until 1803. Weeks after taking full control, Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States. This happened after his forces were defeated in Saint-Domingue. Napoleon had been trying to regain control there after the Haitian Revolution.

In the early 1800s, many refugees from Saint-Domingue came to New Orleans. This nearly tripled the city's population. More than half of the refugees settled in Louisiana. Thousands of Saint Dominican refugees, both white and Creole of color, arrived. They sometimes brought enslaved people with them. Governor William C.C. Claiborne wanted to keep out more free black men. But Louisiana Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking Creole population. More refugees were allowed in, including those who had first gone to Cuba. Cuban officials deported many Saint Dominican refugees because of French plans in Spain. After the Purchase, many Americans also moved to Louisiana. Later European immigrants included Irish, Germans, and Italians.

Almost 90 percent of immigrants in the early 1800s settled in New Orleans. The 1809 arrival of Saint Dominicans from Cuba brought 2,731 white people, 3,102 Creoles of color, and 3,226 enslaved people. This doubled the city's population. The city became 63 percent black, a higher percentage than Charleston, South Carolina.

The rich families from Saint-Domingue were mostly not found in Louisiana. Most Saint Dominican refugees who influenced Louisiana Creole culture came from the lower classes. This included families like Louis Moreau Gottschalk's and Rodolphe Desdunes'.

The arrival of Saint Dominican Creoles boosted Louisiana's culture and industry. This helped Louisiana become a state quickly. One Louisiana Creole noted how fast his homeland developed: "Nobody knows better than you just how little education the Louisianians of my generation have received and how little opportunity one had twenty years ago to procure teachers... Louisiana today offers almost as many resources as any other state in the American Union for the education of its youth. The misfortunes of the French Revolution have cast upon this country so many talented men. This factor has also produced a considerable increase in the population and wealth. The evacuation of Saint-Domingue and lately that of the island of Cuba, coupled with the immigration of the people from the East Coast, have tripled in eight years the population of this rich colony, which has been elevated to the status of statehood by virtue of a governmental decree."

When the United States took over Louisiana, American settlers arrived. This led to a cultural clash. Some Americans were surprised by Louisiana's culture. They saw the French language, Roman Catholicism, the free class of Creoles of color, and strong African traditions. They pressured Governor William C. C. Claiborne to change things.

Before the Civil War, major crops were sugar and cotton. These were grown on large plantations along the Mississippi River. Enslaved people did the work. Plantations were set up in the French style. They had narrow riverfronts for access and long plots going inland.

In the American South, slavery became tied to race. Children born to enslaved mothers were also enslaved. This created many mixed-race enslaved people over time. White Americans often divided society into only "white" and "black."

There was a growing population of free black people. But they generally did not have the same rights as Creoles of color in Louisiana. Under French and Spanish rule, Creoles of color held public office and served in the militia. For example, about 80 free Creoles of color fought in the Battle of Baton Rouge (1779) in 1779. And 353 free Creoles of color fought in the Battle of New Orleans in 1812. Some of their descendants later fought in the American Civil War.

When Governor Claiborne made English the official language, French Creoles in New Orleans were very upset. They protested in the streets. They did not want to change overnight. Upper-class French Creoles also thought many Americans were rude. This included the rough Kentucky boatmen who visited the city.

Realizing he needed local support, Claiborne made French an official language again. French continued to be used in government, public places, and the Catholic Church. Most importantly, Louisiana French and Louisiana Creole remained the languages of most people in the state. English and Spanish were minority languages.

Creole Culture Before the Civil War

Louisiana grew quickly after becoming a U.S. state.

By 1850, one-third of all Creoles of color owned property worth over $100,000. Creoles of color were wealthy business owners, doctors, and other respected professionals. They owned estates and properties in French Louisiana.

Almost all boys from wealthy Creole families were sent to France. There, they received an excellent classical education.

Louisiana, as a French and Spanish colony, had a three-tiered society. This was similar to other Latin American and Caribbean countries. It had an aristocracy (large landowners), a bourgeoisie (prosperous, educated city dwellers), and peasantry (indentured servants, enslaved Africans, and Creole farmers). This mix of cultures and races created a unique society in America.

Creole Identity and Race

During the Age of Discovery, people born in the colonies were called Creoles. This was to tell them apart from new arrivals from France, Spain, and Africa. Some Native Americans, like the Choctaw people, also married Creoles.

Like "Cajun," "Creole" is a popular name for cultures in southern Louisiana. "Creole" generally means "native to a region." But its exact meaning changes depending on where it's used. Creoles felt they needed to be different from the many American and European immigrants. These new people came after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. "Creole" still describes the heritage and customs of the various people who settled Louisiana early on. Besides French Canadians, Creole culture includes influences from Native tribes like the Chitimacha and Houma people. It also includes West Africans, Spanish-speaking Isleños, and French-speaking Gens de couleur from the Caribbean.

Mixed-race Creoles quickly gained education, skills, businesses, and property. Many in New Orleans were skilled craftspeople. They were mostly Catholic and spoke Colonial French. They kept French social customs, mixed with their other backgrounds and Louisiana culture. Creoles of color often married within their group. This helped them keep their social class and culture.

Under French and Spanish rule, Louisiana had a three-tiered society. This was like Saint-Domingue (Haiti) and other Latin colonies. It had elite landowners, a wealthy urban group, and a larger class of enslaved people and farmers.

Creoles of color carefully protected their status. The American Union treated Creoles as unique people. This was due to the Louisiana Purchase Treaty of 1803. By law, Creoles of Color had most of the same rights as white Creoles. They could challenge laws in court and often won cases against white people. They owned property and created schools for their children.

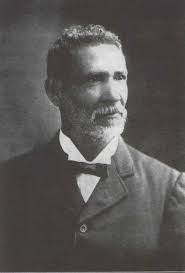

Race was not as central as in Anglo-American culture. Often, family standing and wealth were more important in New Orleans. The Creole civil rights activist Rodolphe Desdunes explained the difference between Creoles and Anglo-Americans: "The groups (Latin and Anglo New Orleanians) had 'two different schools of politics [and differed] radically ... in aspiration and method. One hopes [Latins], and the other doubts [Anglos]. Thus we often perceive that one makes every effort to acquire merits, the other to gain advantages. One aspires to equality, the other to identity. One will forget that he is a Negro to think that he is a man; the other will forget that he is a man to think that he is a Negro."

After the U.S. bought Louisiana, mixed-race Creoles of color resisted American ideas about race. In the American South, slavery meant anyone with African ancestry was seen as lower than whites. This ignored Louisiana's long-standing three-part system of whites, blacks, and Creoles of color.

There was also a large German Creole group. They lived in parishes like St. Charles and St. John the Baptist. This area was called the "German Coast." Over time, many of these groups joined the French-speaking Creole culture. They often adopted the French language and customs.

The American Civil War promised rights for enslaved people. But many Creoles of color who were already free worried about losing their identity. Americans did not legally recognize a three-tiered society. Still, some Creoles of color, like Thomy Lafon and Victor Séjour, supported ending slavery. One Creole of color, Francis E. Dumas, freed his enslaved people. He then organized them into a company in the Federal Louisiana Native Guards. Alexander Dimitry was one of the few people of color to lead in the Confederate Government. His son, John Dimitry, fought with the Confederate Louisiana Native Guards.

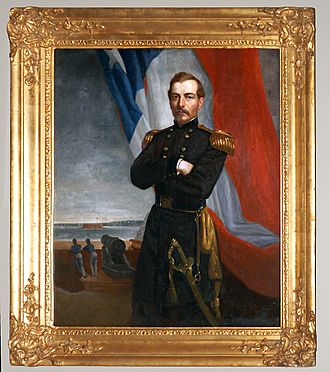

After the Civil War, more Anglo-Americans arrived. They slowly changed Louisiana's three-tiered society. They classified everyone as "black" or "white." During Reconstruction, Democrats regained power in Louisiana. They used groups like the White League to stop black people from voting. Democrats enforced white supremacy by passing Jim Crow laws. These laws and a new constitution at the turn of the 20th century stopped most black people and Creoles of color from voting. Some white Creoles, like General P. G. T. Beauregard, spoke out against racism. They supported civil rights and voting rights for black people. They helped create the Louisiana Unification Movement. This movement called for equal rights and opposed segregation.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) supported the "separate but equal" policy. This led to segregation in the South. Some white Creoles, influenced by white American society, started saying "Creole" only applied to white people.

Sybil Kein suggests that white Creoles fought to redefine themselves. They were especially against writer George Washington Cable's stories. Cable wrote about the mixed-race Creole society. Kein believes Cable's novel The Grandissimes showed white Creoles trying to hide their family ties to Creoles of color. Kein writes: "There was a veritable explosion of defenses of Creole ancestry. The more novelist George Washington Cable engaged his characters in family feuds over inheritance, embroiled them in ... with blacks and mulattoes and made them seem particularly defensive about their presumably pure Caucasian ancestry, the more vociferously the white Creoles responded, insisting on purity of white ancestry as a requirement for identification as Creole."

In the 1930s, Governor Huey Long joked about these Creole claims. He said you could feed all the "pure white" people in New Orleans with a small amount of food. This showed how few people truly had no mixed ancestry. But efforts to force American racial categories on Creoles continued. In 1938, a court ruled that any African ancestry meant a person was "colored."

From 1949 to 1965, Naomi Drake worked for New Orleans' Bureau of Vital Statistics. She tried to enforce these strict racial rules. She changed records to classify mixed-race people as black if she found any African ancestry. She did not tell people about these changes. Drake's workers even checked obituaries. They looked for clues that a white person might be "really" black. This included black relatives or services at black funeral homes. She would then change their death certificates to "black." Not everyone accepted Drake's actions. Thousands of cases were filed against her office. People protested her withholding legal documents. This caused much trouble, and she was fired in 1965.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the "Cajun Renaissance" brought attention to Cajun identity. Creole identity received less attention. However, in the late 2010s, there has been a small but important return of Creole identity. This includes white people whose parents or grandparents identified as Cajun or simply French.

Today, French-language media in Louisiana often use Créole in its original, broad sense. This means it does not refer to race. Some English-language groups also question the racial divide between Cajun and Creole. Documentaries explore how Creole culture impacts what is called Cajun.

Creole Culture

Creole Cuisine

Louisiana Creole cuisine is a special cooking style from New Orleans. It started in the early 1700s. It uses what is called the Holy trinity: onions, celery, and green peppers. This cooking style grew from European, African, and Native American influences. A different style of Creole or Cajun cooking is found in Acadiana.

Gumbo is a traditional Creole dish from New Orleans. It has French, Spanish, Native American, African, German, Italian, and Caribbean influences. It is a thick stew or soup, often made with a mix of seafood (like shrimp, crabs, or crawfish) or meats (like sausage, chicken, or alligator). Gumbo is often seasoned with filé, which is ground sassafras leaves. Both meat and seafood versions include the "Holy Trinity." It is served like a stew over rice. It came from French colonists trying to make bouillabaisse with New World ingredients. The French used onions and celery, like in a traditional mirepoix. But they used green bell peppers instead of carrots. Africans brought okra, a plant common in Africa. Gombo is the Louisiana French word for okra. "Gumbo" is the English version of this word. In Louisiana French, "gombo" still means both the stew and the vegetable. The Choctaw people added filé. The Spanish added peppers and tomatoes. New spices came from Caribbean dishes. The French later used a roux to thicken it. In the 1800s, Italians added garlic. German immigrants introduced eating gumbo with buttered French bread and German-style potato salad.

Jambalaya is another famous Louisiana Creole dish.

Today, jambalaya is often made with seafood (like shrimp) or chicken. Or it can be a mix of both. Most versions use smoked sausage, instead of ham. However, a jambalaya with ham and shrimp might be closer to the original Creole dish.

Jambalaya is made in two ways: "red" and "brown." The "red" version uses tomatoes and is from New Orleans. It is also found in parts of Iberia and St. Martin parishes. It usually uses shrimp or chicken broth. The red-style Creole jambalaya is the original. The "brown" version is linked to Cajun cooking and does not use tomatoes.

Red beans and rice is a dish with Louisiana and Caribbean influences. It started in New Orleans. It has red beans, the "holy trinity" (onion, celery, bell pepper), and often smoked sausage or ham hocks. The beans are served over white rice. It is a famous Louisiana dish. It is linked to "washday Monday." It could cook all day while women did laundry.

Creole Music

Zydeco music started in black Creole communities in southwest Louisiana in the 1920s. It is often called the Creole music of Louisiana. Zydeco is a type of Cajun music. It comes from older Louisiana music styles. Since Louisiana French and Louisiana Creole were common languages, zydeco was first sung only in these languages. Later, Creole musicians like the Chénier brothers and Rosie Lédet added a bluesy sound. They also added English to zydeco music. Today, zydeco musicians sing in English, Louisiana Creole, or Colonial Louisiana French.

Today's Zydeco often mixes swamp pop, blues, and jazz. It also includes "Cajun Music." An instrument unique to zydeco is the frottoir or scrub board. This is a vest made of corrugated aluminum. Musicians play it by rubbing bottle openers or spoons up and down. Another instrument used in both Zydeco and Cajun music is the accordion. Zydeco uses the piano or button accordion. Cajun music uses the diatonic accordion, often called a "squeeze box." Cajun musicians also use the fiddle and steel guitar more often than zydeco players.

Zydeco can be traced back to the music of enslaved African people in the 1800s. It is found in Slave Songs of the United States, published in 1867. The last seven songs in that book have melodies and text in Louisiana Creole. These songs were sung by enslaved people on plantations. They also sang them when they gathered on Sundays at Congo Square in New Orleans.

Spanish Creole people have their own traditional music. This includes Canarian Décimas, romances, ballads, and old Spanish songs. This music came from their ancestors in the Canary Islands in the 1700s. They also adapted their music to other styles, like Mexican Corridos.

Creole Language

Louisiana Creole (Kréyol La Lwizyàn) is a French Creole language. Louisiana Creole people speak it, and sometimes Cajuns and other residents do too. The language has parts of French, Spanish, African, and Native American languages.

Louisiana French (LF) is the French language spoken in Louisiana. People who identify as Creole, Cajun, or French speak it. Some people of Spanish, African-American, white, Irish, or other backgrounds also speak it. People in Louisiana constantly add new words and features to the French language.

Tulane University's French and Italian department states, "In Louisiana, French is not a foreign language." U.S. census numbers show that about 250,000 Louisianans said they spoke French at home.

Among Louisiana's 18 governors between 1803 and 1865, six were French Creoles and spoke French. These included Jacques Villeré and Alexandre Mouton.

According to historian Paul Lachance, white immigrants helped French-speakers stay a majority in New Orleans until about 1830. If many Creoles of color and enslaved people had not also spoken French, the French-speaking community would have become a minority earlier. In the 1850s, white French-speakers were still a strong community. They kept French instruction in two of the city's school districts. In 1862, Union general Ben Butler stopped French instruction in New Orleans schools. State laws in 1864 and 1868 further ended this policy. By the late 1800s, French use in the city had greatly decreased. However, as late as 1902, one-fourth of the city's population spoke French daily. Another two-fourths could understand it perfectly. As late as 1945, some elderly Creole women still spoke no English. The last major French-language newspaper in New Orleans stopped publishing in 1923.

Today, Louisiana French or Louisiana Creole are mostly spoken in rural areas. In the 1940s and 1950s, many Creoles moved to Texas for work. The language and music are still widely spoken there. Houston's 5th ward was called Frenchtown for this reason. Zydeco clubs also started in Houston.

On the other hand, Spanish use has greatly decreased among Spanish Creoles. In the early 1900s, most people in Saint Bernard and Galveztown spoke Canarian Spanish dialect. Their ancestors were from the Canary Islands. But the Louisiana government made English mandatory, especially in schools. Teachers would fine children for speaking Spanish. Now, only a few people over 80 can speak Spanish in these communities. Most young people in Saint Bernard only speak English.

New Orleans Mardi Gras

Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday) in New Orleans, Louisiana, is a world-famous Carnival celebration. It has French colonial roots.

The New Orleans Carnival season starts after Twelfth Night (January 6). This is a time of parades, balls (some are masquerade balls), and king cake parties. It has always been part of the winter social season. Young women's "coming out" parties were once held during this time.

Celebrations are most intense for about two weeks before Fat Tuesday. Fat Tuesday is the day before Ash Wednesday. Usually, there is one big parade each day, if the weather is good. Many days have several large parades. The biggest parades happen in the last five days of the season. In the final week, many events happen throughout New Orleans.

Carnival krewes organize the parades in New Orleans. Krewe float riders throw "throws" to the crowds. Common throws are colorful plastic beads, doubloons (coins with a krewe logo), decorated plastic cups, and small toys. Major krewes follow the same parade schedule and route every year.

Many tourists focus their Mardi Gras activities on Bourbon Street and the French Quarter. But no major Mardi Gras parades have entered the Quarter since 1972. This is because of its narrow streets and overhead obstacles. Instead, major parades start in the Uptown and Mid-City areas. They follow a route along St. Charles Avenue and Canal Street, on the upriver side of the French Quarter.

To New Orleanians, "Mardi Gras" specifically means the Tuesday before Lent. This is the highlight of the season. The term can also mean the whole Carnival season. "Fat Tuesday" or "Mardi Gras Day" always refer only to that specific day.

Creole Places

Cane River Creoles

New Orleans' Creole society gets a lot of attention. But the Cane River area also has a strong Creole culture. Creole people from New Orleans and other groups settled here. These included Africans, Spanish, French, and Native Americans. They mixed together in the 1700s and early 1800s. This community is around Isle Brevelle in lower Natchitoches Parish. Many Creole communities are in Natchitoches Parish, including Natchitoches and Cloutierville. Many of their old plantations still exist. Some are National Historic Landmarks. They are part of the Cane River National Heritage Area and the Cane River Creole National Historical Park. Some plantations are also on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail.

Isle Brevelle is a large area of land. About 16,000 acres are still owned by descendants of the original Creole families. Many Cane River Creole family names are French or Spanish.

Pointe Coupee Creoles

Another historic Creole area is Pointe Coupee. This area is northwest of Baton Rouge. It is known for the False River. The main town is New Roads. A large part of the nearly 22,000 residents can trace Creole ancestry. This area was known for its many plantations and cultural life. This was true during the French, Spanish, and American colonial times.

The people here became bilingual or even trilingual. They spoke French, Louisiana Creole, and English. This was because of the plantation business. The Louisiana Creole language is strongly linked to this parish. Local French and Creole plantation owners and their enslaved Africans created it. It became the main language for many Pointe Coupee residents well into the 1900s. White and black people, and those of mixed ethnicity, spoke the language. Italian immigrants in the 1800s often adopted it too.

Avoyelles Parish Creoles

Avoyelles Parish has a rich history of Creole ancestry. Marksville has many French Creoles. The languages spoken are Louisiana French and English. This parish was created in 1750. The Creole community in Avoyelles parish is active. It has a unique mix of family, food, and Creole culture. A French Creole Heritage day has been held annually in Avoyelles Parish on Bastille Day since 2012.

Evangeline Parish Creoles

Evangeline Parish was formed in 1910 from part of St. Landry Parish. Most of its population came from the North American Creole and Métis influx of 1763. This was after the French and Indian War. Many French Creoles and Métis people left their old homes. They chose to move to the "Territory of Orleans," which is now Louisiana.

These Creole and Métis families generally did not stay in New Orleans. They settled in the higher "Creole parishes" to the northwest. This area includes Pointe Coupee, St. Landry, Avoyelles, and Evangeline Parish. Along with these families came enslaved people from the West Indies.

Later, Saint-Domingue/Haitian Creoles, Napoleonic soldiers, and French families also settled here. One of Napoleon Bonaparte's officers is considered the founder of Ville Platte. This is the main town of Evangeline Parish. General Antoine Paul Joseph Louis Garrigues de Flaugeac and his fellow soldiers settled in St. Landry Parish. They became important public figures.

Many old French, Swiss German, Austrian, and Spanish Creole family names are still found in Evangeline Parish. Some later Irish and Italian names also appear.

In 2013, the Louisiana Legislature recognized Evangeline Parish as one of the Creole Parishes. Other recognized parishes include Avoyelles, St. Landry, and Pointe Coupee. Natchitoches Parish is also recognized as "Creole."

Evangeline Parish's French-speaking Senator, Eric LaFleur, sponsored the bill. The parish's name "Evangeline" comes from Henry Wadsworth's famous poem. It does not mean the parish is Acadian. The adoption of "Cajun" by residents reflects popular culture. This northwestern region was never part of the Acadian settlement area.

The community now hosts an annual "Creole Families Bastille Day (weekend) Heritage & Honorarium Festival." This celebrates Louisiana's multi-ethnic French Creoles. It includes Catholic mass, Champagne toasts, Creole food, and cultural events. There are scholarly lectures and historical information. It is a fun festival for families with free admission and vendor booths.

St. Landry Parish Creoles

St. Landry Parish has many Creoles. This is especially true in Opelousas and nearby areas. Creole traditions and heritage are strong in Opelousas, Port Barre, and other towns. The Roman Catholic Church and French/Creole language are key parts of this culture. Zydeco musicians host festivals all year.

Notable people

See also

In Spanish: Criollos de Luisiana para niños

In Spanish: Criollos de Luisiana para niños

- Creoles of color

- Cane River Creole National Historical Park

- Criollo

- Melrose Plantation

- French Quarter

- Faubourg Marigny

- Tremé

- Little New Orleans

- Frenchtown, Houston

- Magnolia Springs, Alabama

- Institute Catholique

- 7th Ward of New Orleans

- Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

- Native Americans in the United States

- Isleños

- Spanish Americans

- French Americans

- Canarian Americans

- Mexicans

- Saint Dominicans

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |