Casta facts for kids

Casta is a Spanish word that means "lineage" or "family background." In the history of the Spanish Empire in the Americas, this word was used to describe people's race and social standing. Later, in the 1900s, some historians used the term to suggest that colonial society had a strict "caste system" based on race.

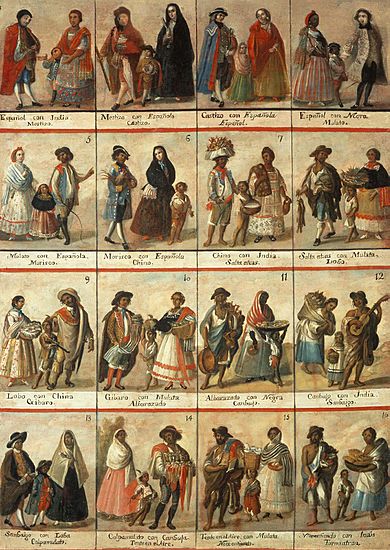

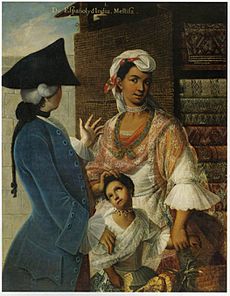

From the very beginning, Spanish America saw a lot of mixing between different groups: Spaniards (españoles), Native Americans (indios), and Africans (negros). The main mixed-race groups officially recognized were mestizo (children of a Spaniard and a Native American) and mulatto (children of a Spaniard and an African). Many other terms were used in 18th-century "casta paintings" for people with mixed Spanish, Native American, and African backgrounds, but these terms were not widely used in official records.

Contents

What "Casta" Means

The word Casta comes from Spanish and Portuguese and has been around since the Middle Ages. It means "lineage" or "family line." The Portuguese word casta is where the English word caste comes from.

How "Casta" Was Used

Historians have long discussed how race, social rank, and status worked in Spanish America. While terms like sistema de castas (system of castes) are used today to describe a race-based social ladder, old records show it wasn't a strict system. People could sometimes move between categories or be called different things depending on the situation.

In the 1700s, "casta paintings" showed a fixed racial hierarchy. However, these paintings might have been an attempt to make sense of a more flexible system. Some historians believe these paintings were a way for the rich and powerful to try and keep strict racial divisions, even as those divisions were fading in real life.

Studies of old records in colonial Mexico also challenge some ideas. For example, not all Spanish immigrants were men, and not all "pure Spanish" people were part of a small, powerful group. Spaniards were often the largest ethnic group in colonial cities, and many Spanish people were poor or did manual labor.

During the Mexican War of Independence, race was a big issue. José María Morelos, a leader who was recorded as Spanish, wanted to get rid of formal racial differences. He said everyone should be called "Americans."

Was There a "Colonial Caste System"?

Since the 1940s, experts have debated how much racial labels affected people's lives. Some scholars, like Ángel Rosenblat and Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán, believed that racial status was the main way Spanish colonial society was organized. This idea became very popular in English-speaking countries.

However, more recent studies in Latin America disagree. They see the "caste system" idea as a flawed way of looking at the colonial period. Many historians now think it might be a modern idea that came about in the 1940s, misinterpreting old colonial terms. They argue that the word "castes" was wrongly used to suggest a strict system like the Caste system in India.

For example, Pilar Gonzalbo's 2013 study, La trampa de las castas (The Trap of the Castes), argues that there was no "caste system" in New Spain (colonial Mexico) that was strictly based on race and forced by power. She also says that the negative messages in some casta paintings were not widespread. They mostly appeared in certain rich families after the Bourbon Reforms, influenced by new ideas of scientific racism.

These paintings often showed few Spanish women in mixed-race families, which doesn't match marriage records showing many Spanish women married men of other backgrounds. This suggests that the paintings were not always accurate. The people who ordered these paintings were likely a small group of wealthy Spanish-Americans who wanted to show their high status and looked down on common people. Therefore, these paintings might not be reliable sources for understanding racism among the general population.

Other historians, like Joanne Rappaport and Berta Ares, also question the idea of a strict "caste system." Ares's 2015 study on the Viceroyalty of Peru found that colonial authorities rarely used the term "casta." When it was used, it was often vague and included poor Spaniards and Native Americans, not just mixed-race people.

Ben Vinson's 2018 study of Mexican archives also supported these findings. He concluded that there was no fixed system for classifying people. Instead, society was quite flexible. Individuals might be identified differently at different times or even identify themselves in ways that benefited them. For example, both mestizos and Spaniards didn't have to pay a special tax (tribute), but they were both subject to the Spanish Inquisition. Native Americans (Indios) paid tribute but were free from the Inquisition. So, a mestizo might pretend to be a Native American to avoid the Inquisition, and a Native American might pretend to be a Mestizo to avoid tribute.

Casta paintings from the 1700s in Mexico have greatly shaped how we understand race in Spanish America today. These paintings tried to show a fixed "system" of racial hierarchy, but modern experts disagree with this idea. These paintings were made by rich artists in New Spain for wealthy viewers, both in the colonies and in Spain. They showed mixtures of Spaniards with other groups, and some of these portrayals were meant to be negative or shocking. So, these paintings are useful for understanding the views of the rich about others, and they also show details of daily life in the late colonial period.

The mixing of different ancestries is now called mestizaje. In Spanish colonial law, mixed-race castas were considered part of the república de españoles (Spanish group), not the república de indios (Native American group). This meant Native Americans had different duties and rights than Spaniards and Mestizos.

Critics argue that the "caste system" idea wrongly compares Spanish America to India's caste system. They say that in Spanish America, there wasn't a closed system where birth determined everything. Instead, the idea of Limpieza de sangre (purity of blood) was more about religion than race. Native Americans and Mestizos, as new Christians, had some limits on certain jobs until they fully converted to Catholicism. However, this didn't stop them from moving up in society. They even had protections that "old Christians" (Spaniards) didn't have, like being free from most taxes (except for Native American tribute) or being exempt from the Holy Inquisition.

Therefore, the ideas of a "caste society" or "caste system" for colonial times are seen as inaccurate by some. They believe these ideas might be part of the "Spanish Black Legend," a negative view of Spanish history. Before the 1940s, historians like Alexander von Humboldt didn't describe the Spanish Empire as a society based on racial segregation.

These critics conclude that colonial societies were more about social class, status, and trade groups than strict race-based divisions. While there was a link between class and race, race was not the main cause of social standing. The purpose of castas was to record family identities for the Spanish or Native American groups, along with their rights and duties. This didn't stop people from moving up in society or joining the nobility. Old church records didn't classify people into as many mixed categories as seen in the casta paintings, suggesting those paintings were more of an artistic trend of the Enlightenment era.

Examples of people of African or Native American descent who achieved high social standing, such as Juan Latino (a Black scholar) or Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (a noble Mestizo writer), are used to show that social mobility was possible. A 1559 law by Philip II of Spain also allowed Mestizos to study in Spain and return without special permission, showing that mixed-race people could move freely within the Spanish monarchy.

"Purity of Blood" and Race

Some historians connect the castas in Latin America to an older Spanish idea called limpieza de sangre (purity of blood). This idea came from Spain's history with Moorish rule and was used to identify people without recent Jewish or Muslim ancestors, or those not convicted by the Spanish Inquisition for heresy.

This concept was linked to religion, family honor, and legitimacy. It's debated how much it was a precursor to modern ideas of race. The Inquisition only allowed Spaniards who could prove they didn't have Jewish or Moorish blood to move to Latin America, though this rule was often ignored. Some Spanish conquerors were Jewish converts, and others, like Juan Valiente, were Black Africans or had Moorish ancestors.

In both Spain and the Americas, Jewish converts who secretly practiced Judaism were punished. Many people executed by the Spanish Inquisition in Mexico were accused of being "Judaizers."

In Spanish America, the idea of "purity of blood" also applied to Black Africans and Native Americans. Since they hadn't been Christian for many generations, they were sometimes suspected of heresy. In all Spanish territories, not having "pure blood" could prevent people from holding public office, becoming priests, or moving to overseas territories. Proving one's ancestry led to a business of creating fake family trees, which was already common in Spain.

However, this didn't stop marriages between Spaniards and Native Americans, just as it hadn't stopped marriages between different religious or racial groups in Spain. Many mixed-race children were considered Spaniards, and some even returned to Spain and joined the nobility, like Juan Cano Moctezuma.

But by the late 1500s, some investigations started to see any connection to Black African ancestry as a "stain." Sometimes, mixtures with Native Americans that produced Mestizos were also seen negatively. While some old pictures show people of African descent dressed richly, the idea that any Black ancestry was a "stain" grew stronger by the end of the colonial period, when biological racism began to appear in the Western world. This trend was shown in the 18th-century casta paintings, which later led to the 20th-century theories about a "Caste System" in Spanish America.

In New Spain, the idea that Native American blood was an "impurity" might have come about as early hopes of training Native American priests faded. Also, the importance of Native American nobility, recognized by the Spanish, decreased, and there were fewer formal marriages between Spaniards and Native American women than in earlier colonial times. By the 1600s, in New Spain, "purity of blood" became linked to "Spanishness and whiteness," but it also connected to social and economic status. So, having an ancestor who did manual labor could also "taint" a family line.

Native Americans in Central Mexico were also affected by "purity of blood" ideas. Spanish laws on "purity of blood" were even supported by Native American communities, which prevented Native Americans with any non-Native American ancestors (Spaniards or Black people) from holding office. Native American nobles had to prove their "pure bloodlines" to keep their rights and privileges. This supported the república de indios, a legal division that separated Native Americans from non-Native Americans (república de españoles).

Casta Classifications and Rules

In Spanish America, people's racial categories were recorded in church baptism records, as required by the Spanish Crown. At first, there were three main groups: "Indians" (indios) for Native Americans, españoles for people from Spain, and negros (blacks) for Africans brought as slaves. Even though mixing was common from the start, mestizos were only slowly recognized as a separate group about 150 years after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Before that, they were often simply identified as Spaniards.

Although many Spanish women came to New Spain, there were fewer of them than men, and fewer Black women than men. So, many mixed-race children of Spaniards and Black people were born from unions with Native American women. This process of race mixing is now called mestizaje.

In the 1500s, as the number of mixed-race individuals grew, especially in cities, the term casta came to be used as a general category for them. However, for the first 150 years of colonial rule, children of mixed marriages were often registered as Spaniards, and only Africans were registered as "Castas." It was only in the last century of colonial rule that "Mestizos" were widely registered as "Castas" instead of "Spaniards."

The Spanish Crown divided its population into two main groups: Native Americans and non-Native Americans. Native Americans were in the República de Indios, while Spaniards, Black people, and mixed-race castas were grouped into the República de Españoles (the Hispanic group). Official counts and church records noted each person's racial category, which helps historians understand their social status, where they lived, and other important information.

Each racial group had its own set of rights and limitations, both by law and tradition. For example, only Spaniards and Native Americans, who were seen as the original societies, had recognized noble families. For everyone else, social privileges and even their accepted racial classification were mostly determined by their social and economic standing.

Church records (for baptisms, marriages, and burials) used three basic categories: español (Spaniards), indio, and color quebrado ("broken color," meaning a mixed-race person). In some parts of colonial Mexico, Native Americans were recorded with other non-Spaniards in the color quebrado register. Spaniards and mestizos could become priests and didn't have to pay tribute to the crown. Free Black people, Native Americans, and mixed-race castas had to pay tribute and were not allowed to become priests. Being called an español or mestizo brought social and financial benefits.

In 1688, a bishop tried to stop Black people and mulattoes from entering the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico. In 1776, the crown issued a law that gave parents control over their children's marriages. The first known Christian marriage in what is now the continental United States was between Luisa de Abrego, a free Black servant, and Miguel Rodríguez, a white Spanish conqueror, in 1565 in St. Augustine, Florida.

The long lists of different terms found in casta paintings were not used in official documents. Censuses only recorded counts of Spaniards, mestizos, Black people, mulattoes, and Native Americans (indios).

Casta Paintings of the 1700s

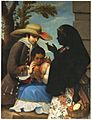

Artworks made mostly in 18th-century Mexico tried to show race mixing as a hierarchy. These paintings have greatly influenced how experts understand racial differences in the colonial era, but they shouldn't be seen as a perfect description of reality. For about a century, casta paintings were made by skilled artists for wealthy viewers. They stopped being produced after Mexico gained independence in 1821, when casta labels were removed. Most casta paintings were made in Mexico, though one group of paintings is clearly from 18th-century Peru.

In colonial times, artists mainly created religious art and portraits. But in the 1700s, casta paintings became a new type of art that was not religious. One exception is a painting by Luis de Mena, which features the Virgin of Guadalupe along with casta groups. Most sets of casta paintings have 16 separate canvases. However, a few, like Mena's and Ignacio María Barreda's, are often shown as examples because they present a single, neat image of racial classification (from the viewpoint of the rich).

It's not fully clear why casta paintings became popular, who ordered them, or who collected them. One expert suggests they might have been a way for Spanish-Americans to show pride in their local identity, as they started to feel more connected to their birthplace than to Spain. Single-canvas casta artworks might have been souvenirs for Spaniards to take back home. Two popular casta paintings by Mena and Barreda are now in museums in Madrid. Only one set of casta paintings is definitely from Peru, ordered by Viceroy Manuel Amat y Junyent in 1770 and sent to Spain.

The Age of Enlightenment in Europe, which focused on organizing knowledge and scientific description, might have led to many series of these paintings. They documented the racial combinations in Spanish territories in the Americas. Many sets still exist (about 100 complete sets in museums and private collections), showing 16 different racial combinations. It's important to remember that these paintings showed the views of the wealthy Spanish-American society and officials. Not all wealthy Spanish-Americans liked casta paintings; one said they showed "what harms us, not what benefits us." Many paintings are in major museums in Spain, but many are still in private collections in Mexico, perhaps kept as a source of pride and a way to show what late colonial Mexico was like.

Some of the best sets were made by famous Mexican artists like José de Alcíbar, Miguel Cabrera, and Juan Rodríguez Juárez. One set by José Joaquín Magón even described the "character and moral standing" of the people shown. These artists worked together in painting guilds in New Spain. At least one Spaniard, Francisco Clapera, also made casta paintings. Most casta paintings are unsigned, and little is known about many of the artists who did sign their work.

Some experts believe the main message of these paintings was the "supremacy of the Spaniards." Many casta paintings visually suggested that mixtures of Spaniards and Spanish-Native American offspring could eventually become "Spaniards" again through marriage with Spaniards over generations. This was seen as "restoring racial purity." A visitor to Mexico in 1774, Don Pedro Alonso O'Crouley, also wrote about this. He said that if a mixed-blood person was the child of a Spaniard and a Native American, the "stigma" of mixed race disappeared after three generations. This was because a Spaniard and a Native American produced a mestizo; a mestizo and a Spaniard produced a castizo; and a castizo and a Spaniard produced a Spaniard. He noted that Native American blood shouldn't be seen as a flaw, as laws gave Native Americans many rights, and Philip II allowed mestizos to become priests.

However, O'Crouley said that this "restoration of racial purity" did not happen for European-African offspring marrying white people. He wrote that from a Spaniard and a Black person, the mixed-blood person kept the "stigma" for generations. Casta paintings showed increasing "whitening" over generations with mixtures of Spaniards and Africans. The sequence often shown was: Spaniard + Negra = Mulatto; Spaniard + Mulatta = Morisco; Spaniard + Morisca = Albino (a racial category meaning "white"); Spaniard + Albina = Torna atrás (meaning "throw back" or "return backwards" to Black ancestry). While Negro, Mulatto, and Morisco were used in colonial documents, Albino and Torna atrás were mostly found in casta paintings.

In contrast, mixtures involving Black people (with both Native Americans and Spaniards) led to many confusing combinations with "fanciful terms." Instead of leading to a new, stable racial type, these mixtures seemed to create disorder. Terms like tente en el aire ("floating in mid air") and no te entiendo ("I don't understand you") were used, as well as terms based on animals like coyote and lobo (wolf).

Castas defined themselves in different ways, and how they were recorded in official documents was often a negotiation between the person and the record-keeper. In real life, many casta individuals were given different racial categories in different documents, showing that racial identity in colonial Spanish America was not fixed.

Some paintings showed the supposed "innate" character of people based on their birth and ethnic origin. For example, one painting by José Joaquín Magón said a mestizo (mixed Native American + Spanish) was "generally humble, tranquil, and straightforward." Another painting claimed "from Lobo and Indian woman is born the Cambujo, one usually slow, lazy, and cumbersome." Ultimately, casta paintings remind us of the biases from the colonial era that linked a person's social status and character to their ancestry, skin color, and birth.

Casta paintings often featured goods from Latin America. The Indias (Native American women) in these paintings were shown as partners to Spaniards, Black people, and castas, meaning they were part of Hispanic society. However, in some casta paintings, they were also shown apart from "civilized society," such as Miguel Cabrera's Indios Gentiles, or indios bárbaros or Chichimecas, who were barely clothed Native Americans in a wild setting. In José María Barreda's single-canvas casta painting, there are 16 standard casta groups, and then in a separate section below are "Mecos." Although the "barbarian Indians" (indios bárbaros) were fierce warriors, Native Americans in casta paintings are not shown as warlike, but as weak, a common idea that developed during the colonial era.

Examples of Casta Painting Lists

Here are lists of casta terms from three different sets of paintings. Notice that they only agree on the first five combinations, which are mainly the Native American-White mixtures. There is no agreement on the Black mixtures. Also, no single list should be seen as the "official" one. These terms would have changed from region to region and over time. The lists likely show the names the artist knew or preferred, or what the person who ordered the painting requested.

| Miguel Cabrera, 1763 | Andrés de Islas, 1774 | Anonymous (Museo del Virreinato) | |

|

|

|

Casta Paintings

-

De español, Alvina, Torna atrás. Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz (1701-1770)

-

De español y mulata, morisca. Miguel Cabrera, 1763, oil on canvas, 136x105 cm, private collection.

-

Canbujo con Yndia sale Albaracado / Notentiendo con Yndia sale China, oil on canvas, 222 x 109 cm, Madrid, Museo de América

See also

In Spanish: Sistema de castas colonial para niños

In Spanish: Sistema de castas colonial para niños

- Caste system

- Castizo

- Dominant minority

- Filipino Mestizos

- Mestizo

- Mexican art

- Ordenanzas del Baratillo de México

- Race and ethnicity in Latin America

- La Raza

- Zambo

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |