New Spain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Viceroyalty of New Spain

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1521–1821 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Old coat of arms of Mexico, Viceregal capital

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Motto: Plus Ultra

"Further Beyond" |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Left: Flag of Spain (18): first national flag, naval and fortress flag, the last flag to float in continental America, in the Fortress of San Juan de Ulúa; Right: Military flag of the Viceroyalty of New Spain with Cross of Burgundy and Royal or Duchy Crown (military flag)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

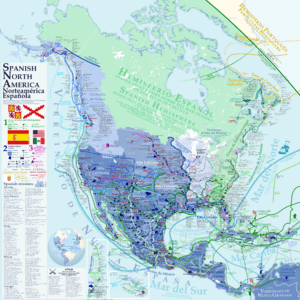

Anachronistic map showing all territories that were ever part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain (dark green). The areas in light green were territories claimed but not controlled by New Spain.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Governorate of the Columbian Viceroyalty (1521–1535) Viceroyalty of the Spanish Empire (1535–1821) |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | México | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish Nahuatl |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Regional languages |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (official) |

||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1521–1556

|

Charles I (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1813–1821

|

Ferdinand VII (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Viceroy | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1535–1550

|

Antonio de Mendoza (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1821

|

Juan O'Donojú (as Political chief superior) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Council of the Indies | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Colonial era | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1519–1521 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 August 1521 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Venezuela annexed to Viceroyalty of New Granada

|

27 May 1717 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Panama annexed to New Kingdom of Granada

|

1739 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1762 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 October 1800 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 February 1819 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Trienio Liberal abolished the Kingdom of New Spain

|

31 May 1820 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 September 1821 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1519

|

10 million | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1810

|

8 million | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish colonial real | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

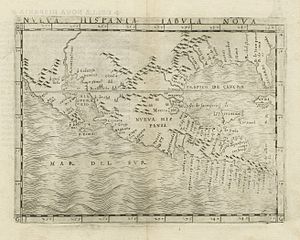

New Spain, officially called the Viceroyalty of New Spain, was a huge territory ruled by the Spanish Empire. It was one of the first areas Spain took over in the Americas. Its capital was Mexico City, built on the ruins of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan. New Spain covered a large part of what is now Mexico and the Southwestern United States. It also included California, Florida, Louisiana, Central America, the Caribbean, and even islands in the Pacific Ocean like the Philippines and Guam.

After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521, Hernán Cortés named the land New Spain. He made Mexico City the new capital. This area became the starting point for more Spanish explorations and conquests. To control this important new land, the Spanish king created the position of a "viceroy" in 1535. The first viceroy was Antonio de Mendoza. New Spain was the first of two main viceroyalties Spain created in the Americas. The other was Peru. Both had many native people and rich silver mines.

New Spain had different regions based on climate, mountains, and how far they were from the capital. Central and southern Mexico had many native people. The northern part was dry and mountainous. In the 1540s, silver was found in Zacatecas. This brought many Spanish miners and officials. Silver mining became very important for New Spain and made Spain rich. New Spain's port of Acapulco was a key stop for trade with the Philippines. This made New Spain a vital link between Spain's empires in the Americas and Asia.

In the early 1800s, New Spain faced problems. Spain was invaded by Napoleon in 1808. This led to a political crisis in New Spain. People born in the Americas wanted more power. This led to the Mexican War of Independence from 1810 to 1821. After the war, the viceroyalty ended. The First Mexican Empire was formed, and Agustín de Iturbide became emperor.

The Crown and New Spain's Government

The Kingdom of New Spain was set up on August 18, 1521. This happened after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. It was a new kingdom in the Americas ruled by the Spanish king. Even though it was far away, New Spain was seen as a kingdom, not just a colony. It was directly under the king's power.

The king had huge power over these lands. He owned the land and controlled the government. He also had great power over the Catholic Church in these territories. This was thanks to a special agreement called the Patronato real. The Viceroyalty of New Spain was officially created on October 12, 1535. A viceroy was appointed as the king's "deputy" or stand-in. This was the first viceroyalty in the Americas.

How Big Was the Spanish Empire?

At its largest, the Spanish king claimed a huge part of North America. This included most of modern Mexico and Central America (except Panama). It also covered much of the United States west of the Mississippi River, plus Florida. The Spanish West Indies, like Cuba and Puerto Rico, were also part of New Spain.

New Spain also claimed islands in Asia and Oceania. These included the Philippine Islands, the Mariana Islands, and parts of Taiwan. Even though Spain claimed these vast lands, it didn't always control all of them. Other European countries, like England and France, set up their own colonies there.

Many areas in the northern part of New Spain were called the "Spanish borderlands." Few Spanish settlers moved there. These areas had fewer native people and didn't seem to have much silver. But later, huge amounts of gold were found in California. This happened after it became part of the U.S. in the mid-1800s.

To protect its claims, Spain sent explorers to the Pacific Northwest. They explored and claimed the coasts of British Columbia and Alaska. To strengthen their control, the Spanish built religious missions and forts called presidios.

Some of the administrative areas in New Spain included:

- Las Californias (Baja California and Alta California)

- Louisiana (from the 1760s)

- Nueva Extremadura (modern Coahuila and Texas)

- Santa Fe de Nuevo México (parts of Texas and New Mexico)

How New Spain Was Governed

The Viceroy's Role

The Viceroyalty was run by a viceroy who lived in Mexico City. The Spanish king appointed the viceroy. The viceroy oversaw all regions, but local groups handled most daily matters. The most important of these were the audiencias. These were like high courts, but they also helped with administration and making laws. They reported to the Viceroy and directly to the Council of the Indies in Spain.

Regional Commands

The next level of government was the Captaincies General. These were somewhat independent from the viceroyalty. The viceroy was also the captain-general for the provinces directly under his control. Examples included the Captaincy General of the Philippines and Guatemala. Two other areas, Spanish Florida and Spanish Louisiana, were called governorates.

High Courts

High courts, or audiencias, were set up in important Spanish settlements. In New Spain, the first high court was created in 1527. This was even before the viceroyalty was officially formed. These courts were in places like Santo Domingo, Mexico City, Guatemala, and Manila.

Audiencia districts also included smaller areas called gobernaciones (provinces). These were first set up by explorer-governors. Provinces facing military threats were grouped into captaincies general. The viceroy was the captain-general for provinces under his direct command.

Local Government

At the local level, there were over 200 districts. These were in both native and Spanish areas. They were led by a corregidor or an cabildo (town council). Both had powers to judge and manage. In the late 1700s, new officials called intendants were introduced. They had broad financial powers. This reduced the power of viceroys and local councils. These new divisions later became the basis for nations in Central America and the first Mexican states.

Intendancies of the 1780s

As part of the Bourbon Reforms in the 1700s, Spain created new administrative units called intendancies. These were meant to give the king more control over the viceroyalty. They aimed to reduce the power of local leaders and improve the economy. Reforms included:

- More public involvement in community matters.

- Giving undeveloped land to native people and Spaniards.

- Stopping corrupt practices by local officials.

- Encouraging trade and mining.

- Setting up a new system of dividing territory.

These changes were not always popular. Viceroys and church leaders often opposed them. Many of the intendancy borders later became the borders of Mexican states after independence.

History of New Spain

The history of New Spain lasted for 300 years. It began with the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–1521). It ended with the Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821).

After the Spanish conquest in 1521, Spanish rule began. Groups like the Council of the Indies and the Audiencia were created to keep control. Native people were often forced to become Christians. Spanish and native cultures also started to mix.

During the 1500s and 1600s, Spanish settlers built important cities. These included Mexico City, Puebla, and Guadalajara. New Spain became a key part of the Spanish Empire. The discovery of silver in Zacatecas and Guanajuato greatly boosted the economy. This also led to conflicts like the Chichimeca War. Missions and forts were built in the northern areas. This helped Spain expand and control lands that are now part of the southwestern United States.

The 1700s saw the Bourbon Reforms. These changes aimed to modernize and strengthen the government and economy. They included creating intendancies, increasing military presence, and centralizing royal power. The Jesuits were expelled, and economic groups were formed. All these efforts aimed to make the empire more efficient and bring in more money for the king.

New Spain's decline ended in the early 1800s with the Mexican War of Independence. It started in 1810 with Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla's Cry of Dolores. The war against Spanish rule lasted eleven years. Finally, a former Spanish military officer, Agustín de Iturbide, joined forces with rebel leader Vicente Guerrero. This led to independence. In 1821, New Spain officially became the independent nation of Mexico. This ended three centuries of Spanish rule.

Economy

After the conquest, Spanish leaders gave their men grants of native labor and tribute. These were called encomiendas. This system was based on how the Aztecs had collected tribute from native communities. It often led to the mistreatment of native people. Some leaders, like Bishop Bartolomé de las Casas, suggested bringing African slaves to replace them. But he later regretted this when he saw how badly African slaves were treated.

In colonial Mexico, "encomenderos de negros" were Portuguese slave traders. They were allowed to operate in Mexico to bring in slaves.

In Peru, another forced labor system called the mit'a was used for silver mines. But in New Spain, labor for mines was different. Most of Mexico's mining areas were outside where many native people lived. So, mines in northern Mexico used African slave labor and paid native workers. Native people who came to the mining areas were from different places. They quickly adopted Spanish culture. Mining was hard and dangerous, but the wages were good.

The Viceroyalty of New Spain was Spain's main source of income in the 1700s. This was thanks to a boost in mining under the Bourbon Reforms. Important mining centers like Zacatecas and Guanajuato had been set up in the 1500s. Silver mining in Mexico brought in more money for the king than any other Spanish territory.

The red dye cochineal was also an important export. It was produced mostly by native farmers in central Mexico and Oaxaca. Cacao and indigo were also important exports. But these were often traded within the viceroyalties due to piracy.

New Spain had two main ports: Veracruz on the Atlantic and Acapulco on the Pacific. Manila in the Philippines was the main port in Asia. These ports were vital for trade routes. Goods from Asia came to Acapulco via the Manila Galleon. Then they were moved overland to Veracruz. From Veracruz, they were shipped to Cádiz in Spain. These ships carried goods from Asia, plus silver and other resources from Mexico and Central America. In the 1500s, Spain received a huge amount of gold and silver from New Spain.

However, this wealth didn't always help Spain grow. Much of it was spent on wars in Europe. Also, British and Dutch pirates often attacked Spanish ships. This led to a "transfer of wealth" from the Americas to northern Europe.

Regions of Mainland New Spain

During the colonial period, different regions of New Spain developed in their own ways. Spanish settlements and institutions grew in the Mesoamerican heartland, where the Aztec Empire once was. This was in Central Mexico.

The South (like Oaxaca and Yucatán) had many native people. But it didn't have many resources that interested Europeans. So, fewer Europeans settled there, and native cultures remained strong.

The North was mostly dry land with nomadic native groups. When silver was found there, the Spanish tried to control these groups to work the mines. But much of northern New Spain had few people. The Spanish king and later Mexico didn't fully control this region. This made it open to expansion by the United States later on.

Mexico City was the main center of power. But other regions, called "provinces," were also important. They grew by producing goods and trading them. Many regional economies focused on supporting the export of goods.

Central Region

Mexico City: The Capital

Mexico City was the heart of the Central region and all of New Spain. Its growth was key to the whole viceroyalty. It was the seat of the Viceroyalty, the main Catholic Church office, and the merchants' guild. It was also home to the wealthiest families. Mexico City was the largest city in the Americas for many years. It had many people of mixed races.

From Veracruz to Mexico City

Important regional growth happened along the main road from the capital to the port of Veracruz. This area included the valleys of Puebla, Mexico, and Toluca. These valleys were connected by main roads. These roads helped move important goods and people to key areas.

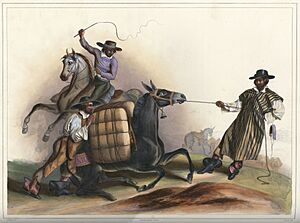

Even in this rich region, moving goods and people was hard. There were no major rivers, and the land was uneven. This was a big challenge for New Spain's economy. It remained a problem until railroads were built in the late 1800s. In colonial times, mule trains were the main way to transport goods. Mules were used because unpaved roads and mountains made carts difficult.

In the late 1700s, the king tried to improve the roads. The Camino Real (royal road) between Veracruz and the capital had some paved parts and bridges. This was done even with protests from some native villages. The king decided road improvements were good for the military and for trade. But the lack of government investment in roads had long-lasting effects.

Veracruz: Port City and Province

Veracruz was the first Spanish settlement in New Spain. It remained the only major port on the Gulf Coast. The land around the port made local development difficult. The journey from the port to the central plateau was a tough climb of 2,000 meters in just over 100 kilometers. The narrow, slippery road was dangerous for mule trains. Many mules and their cargo fell to their deaths.

Because transport was so hard, only valuable, small goods were shipped across the Atlantic. This encouraged local production of food, simple clothes, and other goods for the local market. New Spain grew a lot of sugar and wheat, but it was all used within the colony.

Veracruz was a small port city. Its hot, unhealthy climate didn't attract many permanent settlers. Its population never reached 10,000. Many Spanish merchants preferred to live in the cooler highland town of Jalapa. For a while (1722–1776), Jalapa became more important than Veracruz. It was allowed to host the royal trade fair for New Spain. It became a hub for goods from Asia (via the Manila Galleon to Acapulco) and Europe.

Some Spaniards also settled in the mild area of Orizaba. This area had varied elevations but was mostly temperate. Some lived in semitropical Córdoba. It was founded in 1618 as a Spanish base against runaway slaves (cimarrón) who attacked mule trains. Some runaway slave settlements gained independence. One, led by Gaspar Yanga, became the town of San Lorenzo de los Negros de Cerralvo.

European diseases quickly affected the native populations in Veracruz. So, Spaniards brought in African slaves. They were either an alternative to native labor or replaced it entirely. A few Spaniards took over good farmland left empty by the decline in native population. Parts of the province could grow sugar. By the 1530s, sugar production had begun. New Spain's first viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza, set up a sugar estate in Orizaba.

Native people didn't want to grow sugarcane. They preferred their own food crops. So, African slave labor became vital for sugar estates. From 1580 to 1640, many African slaves were brought to New Spain. Many stayed in the Veracruz region. Even after this period, black slaves remained important to Córdoba's labor force. They made up 20% of the population there, much higher than in other areas of New Spain.

In 1765, the king created a monopoly on tobacco. This affected farming and manufacturing in Veracruz. Tobacco was a valuable product. The king wanted to get steady tax money from it. So, he limited where tobacco could be grown. He also set up factories for finished products and licensed stores. Crown income from tobacco increased.

In 1787, Veracruz became an intendancy as part of the new administrative changes.

Valley of Puebla

Puebla de los Angeles was founded in 1531 as a Spanish settlement. It quickly became Mexico's second most important city. It was located on the main road between the capital and Veracruz. It had fertile land and many native people. This made Puebla a good place for new Spanish settlers. If Puebla had had rich silver, it might have been even more important. In 1786, it became the capital of an intendancy.

Puebla became the seat of the richest church area in New Spain. Its income from farming was twice that of Mexico City's church area. In its first 100 years, Puebla was rich from wheat farming and other agriculture. It also manufactured woolen cloth for the local market. Merchants and artisans were important to the city's economy.

Puebla was a social experiment to settle Spanish immigrants without encomiendas. It was a Spanish city, not built on an existing native city. But it had many native residents. It was located in a fertile area on a plateau. It was also at the center of the trade route between Veracruz, Mexico City, and Oaxaca.

Puebla was far enough from Mexico City (about 160 km) to have some independence. Its Spanish town council had a lot of freedom. This structure helped the king control the power of other groups.

From 1531 to the early 1600s, Puebla's farming grew. Small Spanish farmers planted wheat. Puebla became New Spain's "breadbasket." It also became a center for manufacturing and trade. The city was exempt from sales tax and import/export duties for its first century. This helped trade grow.

Puebla had many workshops (obrajes) that produced textiles. These supplied New Spain and even markets in Guatemala and Peru. Immigrants from a Spanish town called Brihuega brought textile skills and money to Puebla. This helped Puebla's economy grow. Many workshops in Puebla employed up to 100 workers. They had wool, water for mills, and labor (free native people, jailed native people, African slaves). Puebla made rough cloth and also high-quality dyed cloth using cochineal from Oaxaca and indigo from Guatemala. But by the 1700s, Querétaro became the main producer of woolen textiles.

In 1787, Puebla became an intendancy as part of the new administrative changes.

Valley of Mexico

Mexico City was the main city in the Valley of Mexico. But the valley also had many native people. More and more Spanish settlers moved in. The Valley of Mexico had many former native city-states that became native towns. These towns were still ruled by native leaders under the Spanish king. The native towns near the capital were desired by encomenderos and friars.

Native towns supplied the capital with food and labor. The gradual drying of the lake system created more dry land for farming. But the decline in native population in the 1500s allowed Spaniards to get more land. One area that kept strong native land ownership was the southern freshwater area. It supplied fresh produce to the capital. This area had chinampas, which were human-made farming areas in the lake. These chinampa towns kept their strong native character. Native people continued to own most of the land, even though it was close to the Spanish capital. Xochimilco is a key example.

Texcoco was a major cultural center before the conquest. But it declined in the colonial period. Spaniards with ambition moved to Mexico City, so few Spaniards settled in Texcoco.

Tlaxcala, a key ally against the Aztecs, also became less important. But like Puebla, it was not controlled by Spanish encomenderos. No elite Spaniards settled there. Like other native towns, it had small merchants, artisans, farmers, and textile workshops.

North

Parts of northern New Spain became part of the United States. This area is known as the "Spanish Borderlands." The main driver of the Spanish colonial economy was getting silver. In New Spain, there were two major silver mining sites: Zacatecas and Guanajuato.

The region further north of the main mining areas attracted few Spanish settlers. Where there were settled native populations, like in New Mexico and parts of California, native culture remained strong.

Bajío: Mexico's Breadbasket

The Bajío was a rich, fertile lowland north of central Mexico. It was a frontier area between the populated central valleys and the northern desert. In the early 1500s, it had no settled native people. So, it didn't attract Spaniards who wanted to exploit labor. The Bajío developed as a region for commercial farming.

The discovery of silver in Zacatecas and Guanajuato in the mid-1500s boosted the Bajío. It supplied food and livestock to the mines. A network of Spanish towns grew in this farming region. Querétaro also became a center for textile production. Native people moved to the Bajío to work on large farms (haciendas and ranchos) or rent land. They came from different cultures and quickly adopted Spanish ways. They often remained at the bottom of the economic ladder.

Because there were few native workers, Spanish landowners offered incentives to attract them. They lent workers money, which could lead to long-term debt. But it also made jobs more appealing. Workers received textiles, hats, shoes, food, and a guaranteed amount of corn. However, where there were more workers, wages were lower. The northern Bajío, with fewer people, tended to pay higher wages.

In the late colonial period, renting land became common for non-native people in the Bajío. These renters produced for the market. While they could do well in good times, droughts made it risky. Many renters kept ties to the estates to have other ways to earn money. After droughts in the early 1800s, the Mexican War of Independence gained more support in the Bajío. Landowners were evicting tenants for renters who could pay more.

Spanish Borderlands

Areas of northern Mexico became part of the United States in the mid-1800s. These are known as the "Spanish Borderlands." During Spanish rule, this area had very few people, even native ones.

The Spanish king used three main ways to expand and control these territories:

Missions and the Northern Frontier

The town of Albuquerque (modern Albuquerque, New Mexico) was founded in 1706. Other Mexican towns included Paso del Norte (modern Ciudad Juárez), founded in 1667. From 1687, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino founded over twenty missions in the Sonoran Desert.

From 1697, Jesuits built eighteen missions in the Baja California Peninsula. In 1691, explorers visited Texas and named a river and settlement San Antonio.

New Mexico

In 1591, the king ended the long Chichimeca War by making peace with the native tribes in northern Mexico. This allowed expansion into the 'Province of New Mexico'. In 1595, Juan de Oñate received permission to explore and conquer New Mexico. He became the general of New Mexico.

Oñate created 'The Royal Road of the Interior Land' (El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro). This road connected Mexico City to the Tewa village of Ohkay Owingeh. He also founded the Spanish settlement of San Gabriel de Yungue-Ouinge. Oñate later learned that New Mexico had few resources worth large-scale colonization. He resigned as governor in 1607.

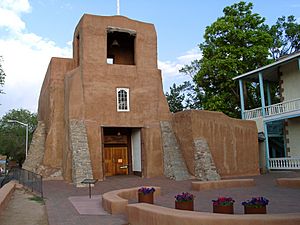

In 1610, Pedro de Peralta, a later governor, established Santa Fe. Missions were built to convert native people and manage farming. The native people resented being forced to convert and work. This led to the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, which drove out the Spanish.

After the Spanish returned in 1692, they reduced efforts to change native culture. They gave large land grants to each Pueblo and appointed a public defender for their rights. In 1776, New Mexico came under the new Provincias Internas (Internal Provinces) rule. In the late 1700s, Spanish land grants encouraged individuals to settle large land areas outside missions and pueblos. Many of these became large ranches.

California

In 1602, Sebastián Vizcaíno explored the 'New California' region. He sailed as far north as present-day Oregon. He named many California coastal features.

California wasn't very interesting to the Spanish king until the 1700s. It had no known rich minerals or organized native groups for labor. The discovery of huge amounts of gold in the Sierra Nevada mountains didn't happen until after the U.S. took California in the mid-1800s.

By the mid-1700s, Jesuits had built missions on the Baja California peninsula. In 1767, King Charles III ordered all Jesuits expelled from Spanish lands. José de Gálvez replaced them with Dominicans in Baja California. Franciscans were chosen to build new missions in Alta California.

In 1768, Gálvez was ordered to "Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey." The Spanish colonies there had fewer natural resources than Mexico or Peru. So, they combined defending the territory with converting native people to Christianity.

The Spanish used a system of:

- Missions (21 built between 1769 and 1833) to convert native Californians.

- Forts (four total) to protect missionaries.

- Municipalities (three total) for civilians.

Because California was so far from supplies in Mexico, the system had to be self-sufficient. So, the colonial population remained small and scattered near the coast.

In 1776, the northwestern frontier areas came under a new administration. This was the 'Commandancy General of the Internal Provinces of the North'. In 1804, the king created two new provincial governments from Las Californias. The southern peninsula became Baja California. The northern mainland became Alta California.

Once missions and forts were set up, large land grants encouraged settlement and the creation of California ranchos. The Spanish land grant system wasn't very successful at first. This was because the grants were just royal permissions, not actual land ownership. Under later Mexican rule, land grants gave full ownership, which helped settlement more.

Rancho activities focused on raising cattle. Many landowners copied the wealthy Dons of Spain. Cattle, horses, and sheep were the source of wealth. Native Americans usually did the work. Native-born descendants of Spanish landowners, soldiers, and others became the Californios. Many men married native women.

After the Mexican War of Independence (1821), Mexican land grants increased the rancho system. These land grants and ranchos created land ownership patterns that are still seen in California and New Mexico today.

South

Yucatán

The Yucatán peninsula was somewhat isolated but also connected to Caribbean trade. The main Spanish settlements were Mérida, where officials lived, and Campeche, the port. Trade grew a lot in the 1600s.

Yucatán had many native Maya people. The encomienda system, which used native labor, lasted longer here than in central Mexico. Fewer Spaniards moved to Yucatán. Even though it was a less important area (no rich mines or major exports), it had a mix of Spanish settlers and people of mixed races. Blacks were also an important part of Yucatecan society. The largest group was the native Maya, who lived in their own communities.

In Yucatán, Spanish rule was mostly indirect. This allowed Maya communities to keep much of their culture and political freedom. The Maya community, called the cah, helped keep native culture strong. In terms of economy, the Maya didn't have a big market network before the Spanish arrived. They mostly grew basic crops. Maya women made cotton textiles to help pay their tribute.

The cah kept a lot of land under the control of religious groups called cofradías. These groups helped Maya communities avoid control by colonial officials. Cofradías were usually religious and burial groups. But in Yucatán, they became important landowners. Their income was used for religious purposes and helped the community.

A problem for Yucatán's economy was the poor quality of the limestone soil. It could only support crops for two to three years. Water was also limited, with water-filled sinkholes (cenotes) but few rivers. People had rights to land as long as they farmed it. Native people generally lived in spread-out settlements. The Spanish tried to force them into larger towns. Collective labor farmed the cofradías' lands, growing maize, beans, and cotton. Later, cofradías also raised cattle, mules, and horses.

In the 1600s, patterns shifted in Yucatán and Tabasco. The English took land that Spain claimed but didn't control. This included what became Belize. In 1716–1717, the viceroy of New Spain sent ships to expel the foreigners. Spain then built a fort. But the British kept their territory in the eastern part of the peninsula. In the 1800s, this area supplied guns to the rebellious Maya in the Caste War of Yucatan.

Valley of Oaxaca

Oaxaca had no mineral deposits but many settled native people. So, it developed without many Europeans or large Spanish farms. Native communities kept their land, languages, and identities. Antequera (Oaxaca City) was a Spanish settlement founded in 1529. But the rest of Oaxaca was made up of native towns. Despite being far from Mexico City, Oaxaca was one of Mexico's most prosperous provinces.

The most important product for Oaxaca was cochineal red dye. This dye was made from insects harvested from nopal cacti. Cochineal was a valuable product that was small in volume. It became the second most valuable Mexican export after silver. Oaxaca was its main production region. For native people in Oaxaca, cochineal was important for paying debts. It was also not very difficult work and could be done by older people, women, and children. It didn't require them to move or change their crops.

The repartimiento system involved local officials and Spanish merchants. They loaned cash to native people or communities. In return, they received a fixed amount of a good, like cochineal. Native leaders were often part of this system. They received large amounts of credit and helped collect debts.

Tehuantepec

The Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Oaxaca was important for its short route between the Gulf Coast and the Pacific. This helped both land and sea trade. The province of Tehuantepec was on the Pacific side. Hernán Cortés owned land here, including Huatulco, which was once the main Pacific port.

Gold mining attracted Spaniards early on, but it ended by the mid-1500s. Over time, ranching and trade became the most important activities. The town of Tehuantepec became the center. The region's history can be divided into three periods:

- Early Spanish rule (to 1563): A working relationship with the Zapotec rulers and Cortés's businesses.

- Decline of native power (1563–1660): Growth of the colonial economy and Spanish rule.

- Maturation of structures (1660–1750).

The Villa of Tehuantepec was a major native trade and religious center before the Spanish arrived. It became a center for Spanish and mixed-race settlers, government, and trade.

Cortés's ranches in Tehuantepec were key to the province's economy. They were linked to his other businesses in Mexico. Ranching became the main rural business in Tehuantepec from 1580 to 1640. Since the native population declined in the 1500s, ranching helped Spaniards succeed. It didn't need many native workers.

The ranches produced animals like horses, mules, and oxen. They also raised sheep and goats for meat and wool. Cattle ranching was important for meat, tallow (for candles), and leather. These products were sold far beyond Tehuantepec.

Native communities remained important in Tehuantepec. There were three main groups: the Zapotec, the Zoque, and the Huave. The Zapotecs allied with the Spanish and grew stronger. They continued farming, even with irrigation. Zapotec leaders often protected their communities from Spanish interference.

The Zoque generally declined during the ranching boom. Their corn crops were eaten by animals. Some Zoque became cowboys themselves. The Huave were the most isolated. They used the Pacific coast lagoons for food. They traded dried shrimp, fish, and purple dye to Oaxaca.

The number of African slaves and their descendants is not well known. They worked as artisans in cities and did hard labor in rural areas. Coastal populations were mainly African. Inland, native communities were more common. On Cortés's ranches, black and mixed-race workers were vital for profits.

Tehuantepec was not a site of major historical events, but there was a significant rebellion in 1660–1661 due to increased Spanish demands.

Central America

As the Spanish population grew, the king created the Captaincy General of Guatemala. This governed what became Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. The region was diverse. Provinces far from the capital, Antigua Guatemala, felt neglected. There was a high court (Audiencia) in Guatemala. Because it was far from Spain and Mexico City, local leaders often had a lot of power.

The native population was very large compared to the Spanish. There were few Africans. Spaniards continued to use forced labor and collect tribute from native people. Compared to the mining areas of New Spain, this region had few mineral resources. It had little potential for export products, except for cacao and the blue dye indigo.

Cacao was grown before the Spanish arrived. Cacao trees take years to grow and produce fruit. Cacao boomed in the late 1500s. Then, indigo replaced it as the most important export. Indigo, like cacao, was native to the region. Native people gathered wild indigo for dyeing cloth and trade. After the Spanish arrived, they grew indigo on plantations in Yucatan, El Salvador, and Guatemala. The indigo industry thrived because there was high demand in Europe for a good blue dye. Native workers did the cultivation and processing. The plantation owners were Spanish.

Indigo work was dangerous due to toxins in the plants. It was profitable, especially after the Bourbon Reforms allowed more trade. In the late 1700s, indigo growers formed a trade organization. Some regions were not under Spanish rule, like the Petén and the Mosquito Coast. The English took advantage of weak Spanish control to set up trade posts on the Gulf Coast. They later took Belize. Spanish-born elites (criollos) gained land and wealth from wheat, sugar, and cattle. These products were consumed within the region.

Demographics

The Impact of Epidemics

Spanish settlers brought diseases like smallpox, measles, and typhoid fever to the Americas. Most Spaniards were immune to these diseases. But native peoples had no immunity because these diseases were new to them. At least three major epidemics greatly reduced the population:

- Smallpox (1520–1521)

- Measles (1545–1548)

- Typhus (1576–1581)

During the 1500s, Mexico's native population fell from an estimated 8 to 20 million to less than two million. By the early 1600s, New Spain was a depopulated region. Many cities and farms were abandoned. These diseases did not affect the Philippines in the same way. This was because diseases were already present there due to earlier contact with other foreign groups.

Population in the Early 1800s

Different regions of New Spain conducted censuses to learn about their people. But the first national census was published in 1793. This was known as the "Revillagigedo census." Most of the original data has been lost. What we know comes from studies by academics who saw the data.

Estimates for the total population vary from 3.8 million to 6.1 million. More recent data suggests 5 to 5.5 million people in 1810. The ethnic makeup was fairly consistent:

- Europeans: 18% to 23%

- Mestizos (mixed race): 21% to 25%

- Amerindians (native people): 51% to 61%

- Africans: 6,000 to 10,000

Over nearly 300 years, the number of Europeans and Mestizos grew steadily. The percentage of native people decreased by 13%–17% per century. This was likely due to higher death rates among native people. They often lived in remote areas or were at war with the Spanish. This also made it harder to count them accurately.

| Intendancy/territory | European population (%) | Indigenous population (%) | Mestizo population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| México (only State of Mexico and capital) | 16.9% | 66.1% | 16.7% |

| Puebla | 10.1% | 74.3% | 15.3% |

| Oaxaca | 06.3% | 88.2% | 05.2% |

| Guanajuato | 25.8% | 44.0% | 29.9% |

| San Luis Potosí | 13.0% | 51.2% | 35.7% |

| Zacatecas | 15.8% | 29.0% | 55.1% |

| Durango | 20.2% | 36.0% | 43.5% |

| Sonora | 28.5% | 44.9% | 26.4% |

| Yucatán | 14.8% | 72.6% | 12.3% |

| Guadalajara | 31.7% | 33.3% | 34.7% |

| Veracruz | 10.4% | 74.0% | 15.2% |

| Valladolid | 27.6% | 42.5% | 29.6% |

| Nuevo México | ~ | 30.8% | 69.0% |

| Vieja California | ~ | 51.7% | 47.9% |

| Nueva California | ~ | 89.9% | 09.8% |

| Coahuila | 30.9% | 28.9% | 40.0% |

| Nuevo León | 62.6% | 05.5% | 31.6% |

| Nuevo Santander | 25.8% | 23.3% | 50.8% |

| Texas | 39.7% | 27.3% | 32.4% |

| Tlaxcala | 13.6% | 72.4% | 13.8% |

~Europeans are included within the Mestizo category.

It's important that New Spain's government tried to count native people. Other colonial countries often didn't count native people as citizens. For example, the United States didn't count native people living among the general population until 1860.

After New Spain became independent, the old caste system was abolished. Mentions of a person's caste were removed from official documents. This made it hard to track ethnic groups in later censuses. Mexico didn't conduct another census with race listed until 1921. But even that one is considered inaccurate by modern researchers. Today, Mexico's government has started doing ethno-racial surveys again. Results suggest that population trends for each major ethnic group haven't changed much since the 1793 census.

Culture, Art, and Architecture

Mexico City, the capital of New Spain, was a major center for European culture in the Americas. Some of the most important early buildings were churches and other religious structures. Government buildings included the viceregal palace (now the National Palace) and the Mexico City town council.

The first printing press in the Americas was brought to Mexico in 1539. The first book printed was "La escala espiritual de San Juan Clímaco". In 1568, Bernal Díaz del Castillo finished his book, La Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España. Important writers included Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, and Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora. In 1693, Sigüenza y Góngora published El Mercurio Volante, New Spain's first newspaper.

Architects like Pedro Martínez Vázquez created a very ornate style called Mexican Churrigueresque. This style can be seen in buildings in the capital, Ocotlan, Puebla, and silver-mining towns. Composers such as Manuel de Zumaya and Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla were active from the early 1500s through the Baroque period.

See also

In Spanish: Virreinato de Nueva España para niños

In Spanish: Virreinato de Nueva España para niños

- Criollo people

- Economic history of Mexico

- Filipino immigration to Mexico

- Governor-General of the Philippines

- Historiography of Colonial Spanish America

- History of democracy in Mexico

- History of Honduras

- Index of Mexico-related articles

- List of governors in the Viceroyalty of New Spain

- List of viceroys of New Spain

- Mexican settlement in the Philippines

- Spanish American Enlightenment

- History of Mexico

- History of Guatemala

- History of El Salvador

- List of viceroys of New Spain

- Louisiana (New Spain)

- Supply of Franciscan missions in New Mexico

- Mexican War of Independence

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |