Agustín de Iturbide facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Agustín I |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Posthumous portrait as Emperor of Mexico by Primitivo Miranda, 1865.

|

|||||

| Emperor of Mexico | |||||

| Reign | 19 May 1822 – 19 March 1823 | ||||

| Coronation | 21 July 1822 | ||||

| Predecessor | Monarchy established | ||||

| Successor | Provisional Government (Chronologically) Maximilian I (as Emperor) |

||||

| Prime Ministers |

List

José Manuel de Herrera

|

||||

| President of the Regency of Mexico | |||||

| In office | 28 September 1821 – 18 May 1822 | ||||

| Predecessor | Monarchy established | ||||

| Successor | Juan Nepomuceno Almonte (Second Mexican Empire) | ||||

| Born | Agustín Cosme Damián de Iturbide y Arámburu 27 September 1783 Valladolid, Viceroyalty of New Spain (now Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico) |

||||

| Died | 19 July 1824 (aged 40) Padilla, Tamaulipas, Mexico |

||||

| Burial | 26 October 1838 Mexico City Cathedral |

||||

| Spouse | Ana María Josefa Ramona de Huarte y Muñiz | ||||

| Issue | Agustín Jerónimo, Prince Imperial of Mexico Princess Sabina Princess Juana de Dios Princess Josefa Prince Ángel Princess María de Jesús Princess María de los Dolores Prince Salvador María Prince Felipe Prince Agustín Cosme |

||||

|

|||||

| House | Iturbide | ||||

| Father | José Joaquín de Iturbide y Arreguí | ||||

| Mother | María Josefa de Arámburu y Carrillo de Figueroa | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature |  |

||||

Agustín de Iturbide (born September 27, 1783 – died July 19, 1824) was a key figure in Mexico's fight for independence from Spain. He started as an officer in the Spanish army, fighting against those who wanted Mexico to be free. But in 1820, he changed his mind and joined the independence movement.

Iturbide led a group of former Spanish soldiers and rebels to achieve Mexico's independence in September 1821. After this success, he became the president of a temporary government. A year later, he was declared the first Emperor of Mexico, ruling as Agustín I from May 1822 to March 1823. He then gave up his throne and went to Europe. When he returned to Mexico in July 1824, he was arrested and executed.

Contents

Agustín de Iturbide's Early Life

Agustín Cosme Damián de Iturbide y Arámburu was born in Valladolid, which is now called Morelia, Mexico. This happened on September 27, 1783. He was the fifth child of his parents, but he was the only boy who survived to adulthood. This meant he would eventually lead his family.

Iturbide's parents were wealthy landowners. They owned large farms called haciendas. His father, Joaquín de Iturbide, came from a noble family in Spain. His mother was born in Mexico to Spanish parents, making her a criolla. In those days, your family background was very important for your social standing and career.

Agustín went to a Catholic school called Colegio de San Nicolás. He wasn't a top student, but he learned to be a good horseman while working on his family's farm. In 1805, he joined the royal Spanish army as a second lieutenant. He was promoted to full lieutenant in 1806.

His Marriage and Family Life

In 1805, when he was 22, Iturbide married Ana María Josefa Ramona de Huarte y Muñiz. She came from a wealthy family in Valladolid. Her family owned businesses and land. Her dowry (money or property brought by a bride to her husband) was very large, about 100,000 pesos. With this money, the couple bought a hacienda near land owned by Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, who would later become a leader of the independence movement.

Iturbide's Military Career

In the early 1800s, there was a lot of political unrest in New Spain (Mexico). Iturbide's first military job was helping to stop a rebellion. He quickly became popular among the royalist soldiers, who fought for Spain. He was known as a brave soldier and a great horseman. He earned the nickname "El Dragón de Hierro," meaning "The Iron Dragon."

Iturbide was accused by some people of using his power for personal gain. These accusations were not proven, but they caused him to lose his military position. He refused to take it back because he felt his honor was damaged.

Fighting for the Spanish Crown (1810–1816)

When the War of Independence began in 1810, the rebel leader, Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, offered Iturbide a high rank in his army. But Iturbide refused. He stayed loyal to the Spanish army. He won many battles against the rebels, even when they had more soldiers. He was also known for being very strict with his opponents.

One of Iturbide's first big battles was in 1810 near Toluca. Even though his side lost, Iturbide showed great bravery. He later said it was the only battle he felt he truly lost.

His next important fight was against another rebel leader, Morelos, in his hometown of Valladolid. Iturbide used his skills to break Morelos's attack on the town, forcing the rebels to retreat. For this, he was promoted to captain. He continued to chase rebel forces and was promoted again. In 1813, he became a colonel. From 1813 to 1815, he was Morelos's main military opponent.

In January 1814, Iturbide's forces soundly defeated Morelos's army in Michoacán. This was a turning point in the war, and Morelos's forces never fully recovered. Iturbide and other Spanish commanders continued to pursue Morelos, eventually capturing and executing him in late 1815.

Temporary Removal from Command

After his victories, Iturbide faced accusations of corruption and harsh treatment of civilians. While these claims were not proven, they damaged his reputation. He had gained a lot of personal wealth, and some believed he did so through unfair dealings, like creating monopolies in areas he controlled. In 1816, the viceroy (the Spanish ruler in Mexico) removed Iturbide from his command. However, a year later, with support from powerful people, the charges were dropped, and he was reinstated. Iturbide never forgot the humiliation of being dismissed.

Facing Guerrero's Rebels

In November 1820, Iturbide was fully back in military command. He was tasked with defeating the last remaining rebel group, led by Vicente Guerrero, southwest of Mexico City. For a long time, historians thought Iturbide tried to defeat Guerrero first and then decided to make an alliance. However, new evidence shows that Iturbide and Guerrero were already talking about Mexico's independence before Iturbide even started his mission.

Iturbide Changes Sides

Why the Criollos Rebelled

From 1810 to 1820, Iturbide had fought to keep the Spanish monarchy in power in Mexico. He was a criollo, meaning he was of Spanish descent but born in Mexico. However, things changed in Spain. In 1820, a new constitution was put in place that limited the king's power. Many wealthy Mexicans worried that Spain's government was becoming too weak. They thought that if Mexico became independent, they could protect their way of life and even invite the Spanish king to rule Mexico instead.

Forming an Alliance with Guerrero

Iturbide became convinced that Mexico needed to be independent to protect itself. He decided to lead the independence movement. To succeed, he needed to unite different groups: the liberal rebels, the wealthy landowners, and the Catholic Church.

He wrote a plan called the Plan of Iguala. This plan had three main promises:

- Freedom: Mexico would be independent from Spain.

- Religion: Catholicism would be the only accepted religion.

- Union: All people in Mexico would be treated equally, no matter their background.

This plan aimed to get support from everyone: the rebels, the clergy, and the Spanish-born people living in Mexico. It also suggested a monarchy, which pleased the royalists. Iturbide met with Guerrero, and they agreed to work together. This meeting is known as the "Embrace of Acatempan." On February 24, 1821, the plan was made public. On March 1, 1821, Iturbide was named the head of the Army of the Three Guarantees, with Guerrero's full support.

The Plan of Iguala Explained

The Plan of Iguala was a flexible document. It suggested that the Spanish king, Ferdinand VII, could come to Mexico City to rule. If he didn't, another member of the Spanish royal family would be chosen. If no European ruler came, then Mexico would choose its own leader.

The three guarantees were key:

- Independence from Spain.

- Roman Catholicism as the official religion.

- Equality for all people in the new nation, ending the old caste system and slavery.

The promise of independence brought the rebels on board. The promise of a strong Catholic Church pleased the clergy, who were worried about anti-church ideas from Spain. The promise of equality between Mexicans and Spanish-born people living in Mexico made sure that the wealthy Spanish landowners and their property would be safe. This was important because if they left, it would hurt Mexico's economy.

The plan gained wide support because it offered independence without threatening the powerful classes. Iturbide managed to unite former enemies—rebels and royalists—to fight for Mexican independence. However, their reasons for joining were different, which would cause problems later.

Both the Spanish king and the viceroy in Mexico rejected the Plan of Iguala. But by then, Mexico was very close to independence, and it couldn't be stopped.

Independence and the New Government

Iturbide met with the new Spanish representative, Juan O'Donojú, to discuss the terms. They quickly agreed to the Treaty of Córdoba. This treaty was similar to the Plan of Iguala. It aimed for an independent monarchy for Mexico under the Spanish royal family. If the Spanish king or his brother refused the throne, then the Mexican congress could choose any suitable monarch. This last part was important because it allowed for a non-European ruler if needed.

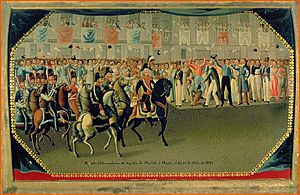

To show the strength of their alliance, Iturbide marched into Mexico City on September 27, 1821, his birthday, with the Army of the Three Guarantees. The people celebrated wildly, decorating the city with the army's colors: red, white, and green. The next day, Mexico was officially declared an independent empire.

Iturbide was named President of the Provisional Governing Junta, a temporary government. This group chose a five-person regency to rule Mexico. Iturbide had a lot of control over this new government. However, former rebel leaders were not included, which caused some tension.

Iturbide moved into a grand palace in Mexico City. He began to live very lavishly. He also demanded special treatment for his army and chose his own ministers. Meanwhile, the Spanish king refused the Mexican throne, and Spain rejected the Treaty of Córdoba, meaning they didn't recognize Mexico's independence.

Emperor Agustín I

Because Spain rejected the treaty and the king refused the throne, no European noble would accept the Mexican crown. In Mexico, there was no local noble family that people would accept as royalty.

The temporary government, led by Iturbide, formed a congress to create the new government. This congress wanted to limit Iturbide's power. It even considered cutting military pay and reducing the army's size. These actions threatened Iturbide's influence.

This led to political instability. To solve this, Iturbide was elected Emperor of Mexico. It's debated whether he truly wanted the crown or if it was forced upon him by popular demand. Some say he orchestrated the public support, while others believe the people genuinely wanted him as their leader because he had freed Mexico. Accounts suggest he initially refused, hoping Ferdinand VII would change his mind, but then accepted.

The U.S. government sent an envoy, Joel Roberts Poinsett, to Mexico. He thought Iturbide's rule wouldn't last long, but the U.S. still recognized Mexico as independent. Poinsett also tried to discuss the U.S. buying Mexico's northern lands, but Iturbide's government refused.

Many historians believe Iturbide already had a lot of power before becoming emperor, so it's unlikely he plotted to crown himself. He wrote in his memoirs that he allowed himself to be placed on a throne he had created for others.

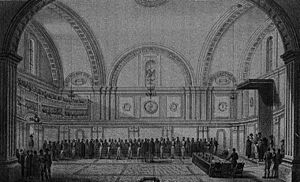

On May 19, 1822, crowds gathered outside Iturbide's palace, shouting for him to take the throne. Iturbide reportedly asked for a night to think about it. The next day, the Congress confirmed him as Agustín I, Constitutional Emperor of Mexico, by a large majority. After his rule, some members claimed they voted for him out of fear, but the Congress later held a private session to confirm his title as lifelong and hereditary.

Iturbide's coronation was a grand ceremony held at the Mexico City Cathedral on July 21, 1822. His wife, Ana María, was crowned empress. As emperor, Iturbide ruled over a vast territory, from what is now Panama in the south to parts of what is now the United States in the north. However, Central American countries only briefly remained part of his empire, declaring their own independence in 1823.

Downfall of the Empire

Problems with Congress

Not everyone was happy with Iturbide as emperor. While the Catholic Church supported him, many republicans (who wanted a government led by elected officials, not a monarch) were disappointed. Some royalists also wanted a European ruler, not Iturbide. Many of these groups turned against him.

The strongest opposition came from the Congress. Many members supported republican ideas and met in secret groups. Iturbide's government also had poor relations with the U.S. because the U.S. was a republic. The Congress believed it had more power than the Emperor. It refused to create a new constitution that included a role for the Emperor. When Iturbide learned of a plot to kidnap him and his family, he dismissed the Congress on October 31, 1822. He then created a new temporary group, the National Institutional Junta, to make laws.

This new group was supposed to create laws, set up a temporary legal system, and call for a new Congress. Iturbide arrested some former members of Congress, but this didn't bring peace. Many important politicians and military leaders, who had supported Iturbide, now turned against him. They felt he had disrespected the idea of national representation. Among them were rebel leaders like Vicente Guerrero and Guadalupe Victoria.

Meanwhile, Mexico faced economic problems. Spain's king wanted to reconquer Mexico, so no European country would recognize Mexico's independence or trade with it. Iturbide's own spending was also a problem. He abolished some old taxes to gain popularity but kept a large, expensive army and lived lavishly. When he imposed a 40% property tax, the wealthy turned against him.

Iturbide soon couldn't pay his army, which made his soldiers unhappy. When people criticized the government, Iturbide censored the press, which only made things worse. Opposition groups began to unite against him. Leaders like Antonio López de Santa Anna started to believe that a republic was needed instead of an empire.

The Plan of Casa Mata

In December 1822, Santa Anna publicly opposed Iturbide with the Plan of Veracruz. This plan called for the old Congress to be brought back to decide the form of government. It didn't specifically demand Iturbide's removal. Iturbide's former ally, Vicente Guerrero, also joined the rebels.

Iturbide sent his trusted general, Echávarri, to fight the rebels. However, Echávarri and several other imperial officers turned against the empire. Santa Anna, joined by Guerrero, and other generals, announced the Plan of Casa Mata. This plan called for a new Congress and declared Iturbide's election as emperor invalid. It also gave provinces the right to govern themselves temporarily. Most provinces accepted the plan. Central American countries, which had been part of Mexico, declared their independence in 1823.

Santa Anna's army marched toward Mexico City. Many military leaders appointed by Iturbide switched sides. Iturbide realized that most of the country supported the Plan of Casa Mata. In March 1823, he reopened the Congress he had closed and offered to give up his throne. He said he chose this to avoid a bloody civil war. However, Congress refused to accept his abdication, saying that accepting it would mean his rule was legitimate. Instead, they declared his election as emperor invalid.

The country was then led by a group of three generals: Guadalupe Victoria, Nicolás Bravo, and Pedro Celestino Negrete.

Iturbide's Exile and Return

On May 11, 1823, Iturbide and his family left Mexico on a British ship, heading for Italy. He began writing his memoirs there. Despite claims that he was wealthy, Iturbide and his family struggled financially in exile. Spain pressured Italy to expel him, so the family moved to England.

In England, he published his autobiography. While in exile, the Mexican Congress declared him a traitor and said he would be killed if he returned to Mexico. Iturbide was unaware of this decree.

Iturbide heard rumors that Spain might try to retake Mexico. He wrote to the Mexican Congress in February 1824, offering his help if Spain attacked. Congress never replied. However, some conservative groups in Mexico convinced Iturbide to return.

Execution and Burial

Iturbide returned to Mexico on July 14, 1824, with his family. He landed in Soto la Marina. He was initially welcomed, but then arrested by General Felipe de la Garza, a man Iturbide had previously pardoned. De la Garza took Iturbide to the nearby village of Padilla.

The local government held a trial and sentenced Iturbide to death. Before his execution by firing squad on July 19, 1824, Iturbide said to the people, "Mexicans! In the very act of my death, I recommend to you the love to the fatherland, and the observance to our religion, for it shall lead you to glory. I die having come here to help you, and I die merrily, for I die amongst you. I die with honor, not as a traitor; I do not leave this stain on my children and my legacy. I am not a traitor, no."

His body was buried in Padilla until 1833. Then, President Antonio López de Santa Anna ordered his remains to be moved to the capital with honors. In 1838, his ashes were finally placed in the Chapel of San Felipe de Jesús in the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral. An inscription there honors him as "Agustín de Iturbide. Author of the independence of Mexico."

Iturbide's Place in History

Iturbide's time as emperor lasted less than a year. However, as the leader who brought about Mexico's independence and its first ruler, he remains a very important figure. For some, a monarchy with a constitution seemed like a good way to create a new state, blending old traditions with new ideas. Historians note that Iturbide showed moments of great political skill, but also made some poor decisions.

Iturbide's approach of creating a plan and using military force to back it became a common pattern in Mexican politics. He can be seen as Mexico's first "caudillo" (a charismatic military leader), using popularity and the threat of force to rule. This was followed by other generals like Antonio López de Santa Anna and Porfirio Díaz.

After Iturbide, Mexico became the First Mexican Republic. General Guadalupe Victoria was elected the first president. The 19th century in Mexico was marked by struggles between different political ideas, often leading to conflict.

Iturbide's Legacy

In early Mexican history, the date of independence celebrations depended on political views. Conservatives celebrated September 27, when Iturbide entered Mexico City. Liberals preferred September 16, to honor Hidalgo's call for rebellion. Today, September 16 is the main independence day. Much of the writing about Iturbide is often critical, seeing him as a hero who later sought personal power.

Iturbide gave Mexico its name, "Mexico," which is commonly used today, even though the official name is "United Mexican States." Another important legacy is the modern Mexican flag. The three colors—red, white, and green—originally represented the three guarantees of the Plan of Iguala: Freedom, Religion, and Union. He also added the image of an eagle on a cactus with a snake, linking the new empire to the ancient Aztec symbol. Iturbide is even mentioned in the Himno Nacional Mexicano, Mexico's national anthem.

Images for kids

-

President Álvaro Obregón, who staged elaborate centennial commemorations of Iturbide in 1921.

See also

In Spanish: Agustín de Iturbide para niños

In Spanish: Agustín de Iturbide para niños

- Declaration to the world

- History of democracy in Mexico

- List of heads of state of Mexico

- Embrace of Acatempan

- Army of the Three Guarantees

- Palace of Iturbide