Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Birth name | Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla Gallaga Mandarte y Villaseñor |

| Born | 8 May 1753 Pénjamo, Nueva Galicia, Viceroyalty of New Spain |

| Died | 30 July 1811 (aged 58) Chihuahua, Nueva Vizcaya, Viceroyalty of New Spain |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Mexico |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1810–1811 |

| Commands held | Generalissimo |

| Battles/wars | Mexican War of Independence |

| Signature |  |

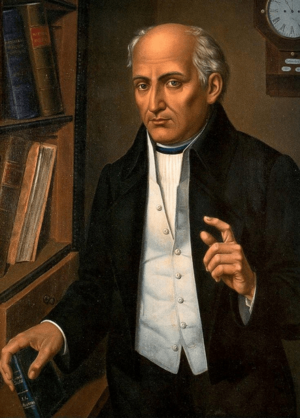

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla (born May 8, 1753 – died July 30, 1811) was a Catholic priest. He became a very important leader in the Mexican War of Independence. Many people call him the "Father of the Nation" because of his role in starting Mexico's fight for freedom.

Hidalgo was a teacher at a school in Valladolid. He learned about new ideas from the Enlightenment, which were popular in Europe. These ideas helped shape his views. He worked as a priest in different towns, including Dolores. In Dolores, he saw that the land was very rich. He tried to help poor people grow olives and grapes. However, the Spanish rulers in New Spain (which is now Mexico) did not want people to grow these crops. They wanted to sell their own crops from Spain.

On September 16, 1810, Hidalgo gave a famous speech called the Cry of Dolores. He asked people to rise up against the Spanish rulers. He wanted them to protect their king, Ferdinand VII, who was held captive in Europe. He marched across Mexico and gathered a large army of about 90,000 farmers and ordinary people. This army attacked the Spanish elite. Hidalgo's troops were not well-trained or well-armed. They fought a well-trained Spanish army at the Battle of Calderón Bridge and were defeated. After this, Hidalgo tried to escape north but was captured and executed.

Contents

Miguel Hidalgo: Mexico's Independence Hero

Early Life and Education

Miguel Hidalgo was born in Pénjamo, New Spain. He was the second child of Cristóbal Hidalgo y Costilla and Ana María Gallaga Mandarte Villaseñor. Both of his parents were criollos, meaning they were of Spanish descent but born in the Americas. His family was well-respected. Miguel's father managed a large farm near Valladolid, where Miguel spent most of his life. He was baptized into the Catholic faith soon after he was born. Miguel had three younger brothers. His mother passed away when he was nine years old.

In 1759, a new king, Charles III of Spain, came to power in Spain. He wanted to make changes to the government in the colonies. Miguel's father wanted Miguel and his brother Joaquín to become priests. He made sure his sons received the best education available.

Becoming a Priest and Teacher

When he was fifteen, Hidalgo went to study at a school in Valladolid. He later joined the Colegio de San Nicolás to prepare for the priesthood. He finished his basic studies in 1770. Then, he went to the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico in Mexico City. He earned degrees in philosophy and theology in 1773.

Hidalgo's education for the priesthood was traditional. He studied Latin, rhetoric, and logic. Like many priests in Mexico, he also learned local languages such as Nahuatl, Otomi, and Purépecha. He also learned Italian and French, which were not common at the time. He was known as "El Zorro" (The Fox) because he was very clever in school. Learning French allowed him to read books about the Enlightenment. These books had new ideas that were forbidden by the Catholic Church in Mexico.

Hidalgo became a priest in 1778 when he was 25. From 1779 to 1792, he taught at the Colegio de San Nicolás Obispo. This was a very important school in New Spain. He taught Latin, arts, and theology. He became the dean of the school in 1790. As dean, Hidalgo continued to study new ideas from Europe. He was removed from his position in 1792 because he changed traditional teaching methods. The Church then sent him to work in other parishes. Finally, he became the parish priest in Dolores, Guanajuato, in 1802.

Hidalgo was a very open-minded priest. He welcomed native people and mestizos (people of mixed heritage) into his home, as well as criollos.

Life in Dolores and Economic Efforts

In 1803, Hidalgo arrived in Dolores. He gave most of his church duties to another priest. He spent his time on business, learning, and helping people. He studied literature, science, how to grow grapes, and how to raise silkworms. He used this knowledge to help the poor people in his area. He started factories to make bricks and pottery. He taught native people how to make leather goods. He also encouraged beekeeping.

Hidalgo wanted to help the local people become more independent. However, these activities went against the Spanish rules. Spain had rules to protect its own businesses and farms. Hidalgo was ordered to stop these activities. These rules, along with the unfair treatment of mixed-race people, made Hidalgo dislike the Spanish-born rulers in Mexico.

A drought in 1807–1808 caused a famine in the Dolores area. Spanish merchants held onto their grain instead of selling it. They hoped prices would go up. Hidalgo tried to stop this, but he was not successful.

The Call for Freedom

The Querétaro Conspiracy

At the same time, a secret group was planning a rebellion in Querétaro City. The mayor, Miguel Domínguez, and his wife, Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez, were part of this group. Military officers like Ignacio Allende and Juan Aldama were also involved. Allende convinced Hidalgo to join them. Hidalgo had many influential friends in the Bajío region and across New Spain.

Trouble in Spain

The situation in Spain also played a big role. In 1807, Spain and France invaded Portugal. French troops then moved into Spain. This made the Spanish people very angry. After some revolts, Napoleon forced the Spanish King and Prince to give up their power. Napoleon then made his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, the King of Spain. This led to more revolts across Spain. The war and instability in Spain affected Mexico and other Spanish colonies.

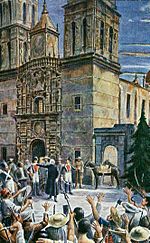

The Cry of Dolores

Hidalgo feared he would be arrested. On the night of September 15, 1810, he ordered his brother and other armed men to free prisoners in Dolores. Eighty people were set free. On the morning of September 16, 1810, Hidalgo held a Mass. About 300 people attended. There, he gave his famous speech, the Grito de Dolores (Cry of Dolores). He called on the people to leave their homes and join him in a rebellion. He said they were fighting against the "bad government" and for their King, Ferdinand VII.

Hidalgo's speech did not directly attack the idea of a king. It also did not criticize the social order in detail. But it clearly showed his opposition to the Spanish government in Mexico. The Grito also stressed loyalty to the Catholic religion. This was something both Criollos and Peninsulares could agree on.

Leading the Fight

Building an Army

Many people supported Hidalgo. Scholars, priests, and many poor people joined him with great excitement. So many native people and mestizos joined that the original goals of the Querétaro group changed. Ignacio Allende, who was a military man, wanted to keep the rebellion focused on Criollo goals. But Hidalgo's actions meant he would lead the movement.

Hidalgo's army started with about 800 men. Many of them were on horseback. They marched through the Bajío area, capturing towns like San Miguel el Grande and Celaya. On September 21, 1810, Hidalgo was named general and supreme commander in Celaya. By this time, his army had grown to about 5,000 people.

Hidalgo's leadership gave the movement a special, almost religious, feeling. Many villagers believed that King Ferdinand VII himself wanted them to follow Hidalgo. This made the rebellion seem very important and right.

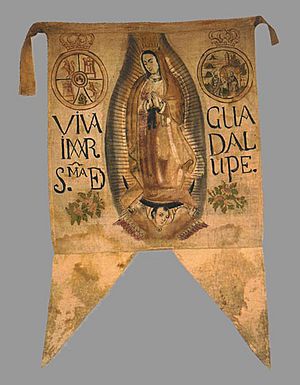

One of their first stops was at the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in Atotonilco. Hidalgo took an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe and put it on a spear to use as his banner. His troops' flags had slogans like: "Long live religion! Long live our most Holy Mother of Guadalupe! Long live America and death to bad government!" The Virgin of Guadalupe was a powerful symbol for the rebels.

Early Victories and Challenges

The size and strength of Hidalgo's movement surprised the Spanish rulers. San Miguel and Celaya were captured easily. However, because the army lacked discipline, the rebels soon started robbing and looting towns. They also executed prisoners. This caused problems between Allende and Hidalgo. Allende tried to stop the violence, but Hidalgo understood why the angry people were acting that way.

On September 28, 1810, Hidalgo arrived at Guanajuato. His rebels were mostly armed with sticks, stones, and machetes. The Spanish and Criollo people in the town hid in a strong building called the Alhóndiga de Granaditas. The rebels attacked for two days and killed many people. Allende strongly protested this violence. While Hidalgo agreed it was terrible, he also said he understood why it happened. These attacks made many Criollos and Peninsulares join forces against the rebels. Hidalgo lost support from some liberal Criollos.

From Guanajuato, Hidalgo went to Valladolid (Morelia) on October 10, 1810, with 15,000 men. In Acámbaro, he was promoted to "generalissimo." He was given a special blue uniform with silver and gold embroidery. It also had a large image of the Virgin of Guadalupe on his chest.

Hidalgo and his forces took Valladolid easily on October 17, 1810. There, Hidalgo spoke out against the Spanish-born rulers. He accused them of being arrogant and unfair. He said they had enslaved people in the Americas for almost 300 years. Hidalgo said the war's goal was to send the Spanish gachupines (a term for Spanish-born people) back to Spain. He said their greed had harmed Mexicans. Hidalgo also made the Bishop-elect of Michoacan, Manuel Abad y Queipo, take back an order that had removed Hidalgo from the Church.

The rebels stayed in Valladolid to prepare to march to Mexico City. Hidalgo was angry when the cathedral was locked to him. He jailed some Spanish people, changed city officials, and took money from the city treasury. On October 19, he left Valladolid for Mexico City.

Hidalgo and his troops marched through several towns. They came very close to Mexico City, reaching the forested mountains of Monte de las Cruces. Here, they fought the royalist forces. Hidalgo's troops made the royalists retreat, but the rebels also suffered many losses.

Retreat and Capture

After the Battle of Monte de las Cruces on October 30, 1810, Hidalgo had about 100,000 rebels. He was in a good position to attack Mexico City. His forces were much larger than the royalist army. The government in Mexico City prepared its defenses. They spread messages about the rebels' violence to scare people. Hidalgo's movement also faced opposition from some native groups and castes in the Valley of Mexico.

Hidalgo's forces came very close to Mexico City. Allende wanted to attack the capital, but Hidalgo decided not to. Historians still debate why he made this choice. One reason might be that his forces were not well-trained and had suffered many losses against trained soldiers. Mexico City was guarded by the best soldiers in New Spain. So, Hidalgo decided to turn away from Mexico City and move north towards Guadalajara.

After turning back, many rebels left the army. By the time he reached Aculco, his army had shrunk to 40,000 men. A Spanish general, Felix Calleja, attacked Hidalgo's forces and defeated them on November 7, 1810. Allende then took his troops to Guanajuato. Hidalgo arrived in Guadalajara on November 26 with over 7,000 poorly armed troops. He was welcomed by the lower classes because he promised to end slavery and taxes on alcohol and tobacco.

Hidalgo set up a new government in Guadalajara. He appointed two ministers. On December 6, 1810, Hidalgo issued a decree that abolished slavery. He threatened death to anyone who did not follow this rule. He also ended the tribute payments that native peoples had to pay. He started a newspaper called Despertador Americano (American Wake Up Call). He sent a representative to the United States to ask for support, but the representative was captured and executed.

During this time, violence by the rebels increased in Guadalajara. People loyal to the Spanish government were captured and executed. The rebels targeted the properties of Criollos and Spaniards. Meanwhile, the royalist army had retaken Guanajuato, forcing Allende to flee to Guadalajara. Allende again argued with Hidalgo about the violence. However, Hidalgo knew the royalist army was coming and wanted to keep his own army happy.

After royalist forces retook Guanajuato, Bishop Manuel Abad y Queipo again removed Hidalgo from the Church on December 24, 1810. Abad y Queipo had been Hidalgo's friend, but he strongly disagreed with Hidalgo's methods and the resulting chaos.

Royalist forces marched to Guadalajara, arriving in January 1811 with about 6,000 men. Allende wanted to defend the city and plan an escape, but Hidalgo decided to fight at the Calderón Bridge just outside the city. Hidalgo had between 80,000 and 100,000 men and 95 cannons. However, the better-trained royalists decisively defeated the rebel army. Hidalgo was forced to flee towards Aguascalientes. On January 25, 1811, Allende and other rebel leaders took military command away from Hidalgo. They blamed him for their defeats. Hidalgo remained the political leader, but Allende took charge of the army.

The rebel army moved north towards Zacatecas and Saltillo. They hoped to get support from the United States. Hidalgo reached Saltillo, where he publicly gave up his military post. He refused a pardon offered by the Spanish general in exchange for his surrender. A short time later, they were betrayed and captured by royalist Ignacio Elizondo at the Wells of Baján on March 21, 1811. They were taken to Chihuahua.

Execution

Hidalgo was handed over to the authorities in Durango. Bishop Francisco Gabriel de Olivares officially removed him from the priesthood on July 27, 1811. A military court then found him guilty of treason. He was executed. Hidalgo's body was buried in the Church of St Francis in Chihuahua. His remains were later moved to Mexico City in 1824.

Hidalgo's death left a gap in the rebel leadership until 1812. The royalist commander, General Félix Calleja, continued to fight the rebel troops. The fighting turned into guerrilla warfare. Eventually, another important rebel leader, José María Morelos Pérez y Pavón, took over. Morelos had also led rebel movements with Hidalgo. He led the rebels until he was captured and executed in 1815.

Legacy

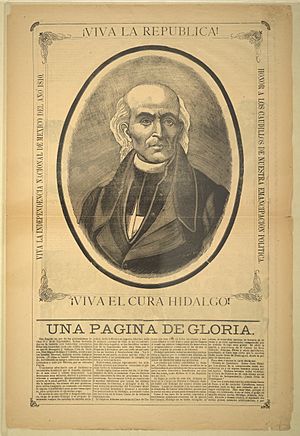

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla is known as the "Father of the Nation" in Mexico. Even though Agustín de Iturbide became the first leader of Mexico in 1821, Hidalgo is celebrated for starting the fight for independence. After Mexico gained independence, people debated which day to celebrate it. Some wanted September 16, the day of Hidalgo's Grito de Dolores. Others wanted September 27, when Iturbide's forces captured Mexico City.

Later, political movements favored Hidalgo. September 16, 1810, officially became Mexico's Independence Day. This is because Hidalgo is seen as the one who started the movement for independence. Many famous Mexican artists have painted Hidalgo. Diego Rivera painted his image in several murals. José Clemente Orozco showed him with a flaming torch of liberty.

The town where Hidalgo was a priest was renamed Dolores Hidalgo in his honor. The state of Hidalgo was created in 1869. Every year on the night of September 15–16, the president of Mexico repeats the Grito from the balcony of the National Palace. This tradition is also followed by leaders in cities and towns across Mexico. Hidalgo County, Texas, is also named after him.

Hidalgo's remains are in the column of the Angel of Independence in Mexico City. A lamp is lit next to them to remember those who gave their lives for Mexican Independence. His birthday is a public holiday in Mexico.

-

Hidalgo was laid to rest at the base of the Angel of Independence, Mexico City

-

Painting of Hidalgo, by José Clemente Orozco, Jalisco Governmental Palace, Guadalajara

-

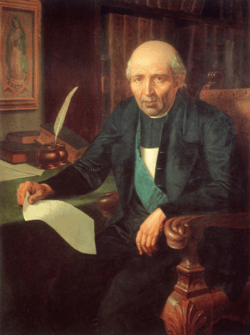

Romantic portrait, by Claudio Linati (1828)

See also

In Spanish: Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla para niños

In Spanish: Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla para niños