Purépecha language facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Purépecha |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tarascan P'urhépecha |

||||

| Pronunciation | [pʰuˈɽepet͡ʃa] | |||

| Native to | Mexico | |||

| Region | Michoacán | |||

| Ethnicity | Purépecha | |||

| Native speakers | 140,000 (2020 census) | |||

| Language family |

Language isolate or an independent language family

|

|||

Distribution of Purépecha in Mexico, green indicates historical language homeland and red is modern-day speakers.

|

||||

|

||||

Purépecha (also called P'urhépecha) is a special language spoken by about 140,000 people in the highlands of Michoacán, Mexico. It is sometimes called Tarascan, but this name was given by Spanish colonizers and is not preferred by the Purépecha people themselves.

Purépecha is known as a language isolate. This means it is not clearly related to any other language family in the world. Imagine it like a unique tree that doesn't belong to any known forest!

This language was very important in the Tarascan State before the Spanish arrived. It was widely spoken in the region during its most powerful time, in the late post-Classic period (a historical time in Mesoamerica). The small town of Purepero even got its name from the people who lived there.

Even though Purépecha is spoken in Mesoamerica (a historical and cultural region in North and Central America), it doesn't share many features with other languages from that area. This suggests it might be a very old language that existed before other languages spread in the region, or perhaps it arrived there more recently.

Contents

What is Purépecha?

Purépecha has long been seen as a language isolate. This means it's not connected to any other known language. Think of it as one of a kind!

Some experts, like Lyle Campbell, agree with this idea. Another researcher, Joseph Greenberg, tried to link it to the Chibchan languages, but most language specialists don't agree with his idea.

There are different ways Purépecha is spoken, like different accents or versions. These are called dialects. Some groups, like SIL International, divide Purépecha into two separate languages. However, Campbell (1997) believes it's all one single language with different ways of speaking.

Where is Purépecha Spoken?

Most Purépecha speakers live in small towns and villages in the highlands of Michoacán. The area around Lake Pátzcuaro was once the center of the Tarascan State. It is still a very important place for the Purépecha community today.

According to Ethnologue, Purépecha is counted as two languages. One is spoken by about 40,000 people (in 2005) near Pátzcuaro. The other is spoken by 135,000 people (in 2005) in the western highlands, around cities like Zamora, Los Reyes de Salgado, Paracho de Verduzco, and Pamatácuaro. These places are all close to the volcano Parícutin.

Some Purépecha speakers have moved to bigger cities like Guadalajara, Tijuana, and Mexico City. They have also formed communities in the United States. The total number of people who speak Purépecha has been growing over the years. For example, it went from 58,000 in 1960 to 120,000 in 2000.

However, the percentage of Purépecha speakers compared to non-speakers is getting smaller. Also, more and more speakers are becoming bilingual, meaning they speak both Purépecha and Spanish. This makes Purépecha an endangered language. Today, fewer than 10% of speakers only speak Purépecha.

History of the Purépecha Language

The Purépecha people have stories that say they moved to their current home from another place, possibly from the Pacific Ocean. Historical records show they were living in Michoacán as early as the 13th century.

According to a historical document called the Relación de Michoacán, the communities around Lake Pátzcuaro were united into a strong Purépecha State. This was done by a leader named Tariácuri from the Uacúsecha group of Purépecha speakers. Around 1300, he began conquering other areas. He put his sons, Hiripan and Tangáxoan, in charge of Ihuatzio and Tzintzuntzan, while he ruled from Pátzcuaro City. By the time Tariácuri died around 1350, his family controlled all the main areas around Lake Pátzcuaro.

His son Hiripan continued to expand the state around Lake Cuitzeo. By 1460, the Purépecha State reached the Pacific Coast at Zacatula. It also moved into the Toluca Valley and reached into the present-day state of Guanajuato in the north.

In the 15th century, the Purépecha state was often at war with the Aztecs. Many Nahua people who lived near Purépecha speakers were moved outside the Purépecha borders. Also, Otomi speakers, who were running away from the expanding Aztec Empire, settled on the border between the two states. This created a strong area where mostly Purépecha was spoken, especially around Lake Pátzcuaro.

When the Spanish arrived during the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Purépecha State at first joined the new Spanish rule peacefully. This new Spanish territory was called New Spain. However, when the Purépecha leader, Cazonci Tangaxuán II, was killed by Nuño de Guzmán, the Spanish took control by force.

There were some exceptions, like the hospital communities created by Vasco de Quiroga, such as Santa Fé de la Laguna. In these places, Purépecha people could live with some protection from Spanish rule. Spanish friars taught the Purépecha people to write using the Latin alphabet. Because of this, Purépecha became a language that was written down in the early colonial period.

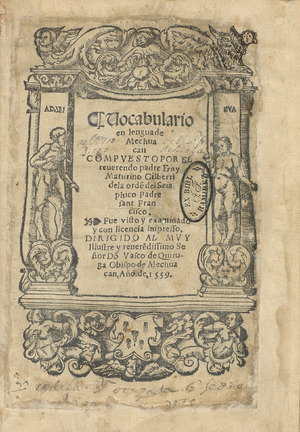

Many written works exist from this time, including dictionaries, religious texts, and land records. Important works include a grammar book (1558) and a dictionary (1559) by Fray Maturino Gilberti.

Around 1700, the status of Purépecha began to change. Throughout the 20th century, the Mexican government tried to encourage people to speak Spanish. They wanted people to stop using their native languages.

However, things changed. In 2003, Mexico's Congress of the Union passed the General Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Peoples. This law gave Purépecha and other native languages in Mexico official status as "national languages." This means they are now recognized and protected, like Spanish, in the areas where they are spoken.

How Purépecha is Written

The official alphabet for Purépecha is called PʼURHEPECHA JIMBO KARARAKUECHA (which means "Purépecha Alphabet"). It uses these letters:

- a b ch chʼ d e g i ï j k kʼ m n nh o p pʼ r rh s t tʼ ts tsʼ u x.

You will only see the letters b, d, g in spelling when they come after m or n. For example, you'll see mb, nd, ng. This shows how the sounds p, t, k are pronounced after nasal sounds.

Sounds of Purépecha

In all Purépecha dialects, the stress accent is important for meaning. This means where you put the stress on a word can change its meaning. Just like in Spanish, a stressed syllable is shown with an acute accent mark.

Here are some examples where stress changes the meaning:

- karáni means 'write'

- kárani means 'fly'

- p'amáni means 'wrap it'

- p'ámani means 'touch a liquid'

Usually, the second part of a word (the second syllable) is stressed. But sometimes, it's the first syllable.

Grammar Basics

Purépecha is an agglutinative language. This means words are formed by adding many small parts (suffixes) to a base word. Think of it like building with LEGOs, where each small piece adds a new meaning. Sometimes, it's even called a polysynthetic language because its words can become very long and complex.

Unlike some other complex languages, Purépecha doesn't combine nouns to make new words, and it doesn't put whole words inside other words. It only adds suffixes to the end of words. It has many suffixes, possibly as many as 160!

The language also uses clitics, which are like small words that attach to other words. Verbs in Purépecha can show 13 different aspects (how an action happens, like if it's ongoing or finished) and 6 different moods (like if it's a command or a possibility).

Purépecha is a double-marking language. This means it marks grammatical relationships on both the main part of a phrase and the words that depend on it.

The language uses grammatical cases and postpositions. Cases are like labels on nouns that show their role in a sentence (like who is doing the action or who the action is happening to). Purépecha has cases like nominative (for the subject), accusative (for the object), genitive (for possession), comitative (for 'with'), instrumental (for 'by means of'), and locative (for 'at' or 'in').

The order of words in a sentence can be flexible. The basic word order is usually described as either SVO (like "Pedro bought the pot") or SOV (like "Pedro the pot bought"). However, speakers often change the word order to emphasize certain parts of the sentence.

Nouns in Purépecha

Nouns in Purépecha change their form to show if they are plural and what their role (case) is in the sentence.

The language tells the difference between plural (more than one) and unspecified numbers. There isn't a special form for just one item (singular).

To make nouns plural, you usually add the suffix -echa/-icha or -cha.

- kúmi-wátsï means 'fox' – kúmi-wátsïcha means 'foxes'

- iréta means 'town' – irétaacha means 'towns'

- warhíticha tepharicha maru means 'some fat women' (literally: women-PL fat-PL some).

The nominative case, which is for the subject of a sentence, doesn't have a special ending. The accusative case, used for direct objects, is marked by the suffix -ni.

Pedrú

Pedrú

Pedro

pyásti

pyá-s-ti

buy-PFV-3P

tsúntsuni

tsúntsu-ni

pot-ACC

'Pedro bought the pot'

The genitive case, which shows possession (like 'whose'), is marked by -ri or -eri.

imá

imá

that

wárhitiri

wárhiti-ri

woman-GEN

wíchu

wíchu

dog

'that woman's dog'

The locative case, which shows location ('at' or 'in'), is marked by -rhu or -o.

kúntaati

ku-nta-a-ti

meet-ITER-FUT-3IND

Maríao

María-o

Maria-LOC

'He'll meet him at María's place' Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

The instrumental case, which means 'with' or 'by means of', is marked by the particle jimpó or the suffix -mpu.

jiríkurhniniksï

jiríkurhi-ni=ksï

hide-INF-3PL

tsakápu

tsakápu

rock

k'éri

k'éri

big

má

má

one

jimpó

jimpó

INS

'They hid behind some big rocks'

ampémpori

ampé-mpu=ri

what-INS

ánchikuarhiwa

anchikuarhi-wa-∅

work-FUT-3SG

'What will he/she work with?'

The comitative case, meaning 'with someone', is marked by the particle jinkóni or the suffix -nkuni.

apóntini

apónti-ni

sleep-INF

warhíti

wárhiti

woman

má

má

one

jinkóni

jinkóni

COM

'to sleep with a woman'

xi

xi

I

niwákani

ni-wa-ka-=ni

go-FUT-1st/2nd-1P

imánkuni

imá-nkuni

DEM-COM

'I'll go with him/her'

To put special emphasis on a noun or noun phrase, the clitic -sï is used.

Ampésï

ampé-sï

what-FOC

arhá

arh-∅-∅-á

eat-PFV-INTERR

Pedrú?

Pedrú

Pedro

'What did Pedro eat?'

kurúchasï

Kurúcha-sï

fish-FOC

atí.

a-∅-tí

eat-PFV-3P

'he ate fish' (meaning: 'fish is what he ate')

Verbs in Purépecha

Verbs in Purépecha change their form to show different aspects (like if an action is finished or ongoing) and moods (like if it's a command or a wish). They also change based on the person and number of the subject (who is doing the action) and the object (who or what the action is done to).

There are also many suffixes that can be added to verbs. These suffixes can describe the shape or position of something, or even body parts that are involved in the action.

The language can change whether a verb needs an object or not. Suffixes can make verbs transitive (meaning they need an object, like "eat an apple"). They can also make them intransitive (meaning they don't need an object, like "sleep").

Purépecha in Media

You can listen to Purépecha-language programs on the radio station XEPUR-AM. This station is located in Cherán, Michoacán. It is part of a project by the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples to support native languages.

Place Names in Purépecha

Many places in Mexico have names that come from the Purépecha language. Here are a few examples:

- Acuitzio – "Place of the snakes"

- Cuerámaro – "Coat of the swamps"

- Cóporo – "Over the big road"

- Cupareo – "Crossroads"

- Tzintzuntzan – "Place of hummingbirds"

- Zurumuato – "Place in straw hill"

Images for kids

-

Distribution of Purépecha in Mexico, green indicates historical language homeland and red is modern-day speakers.

See also

In Spanish: Idioma purépecha para niños

In Spanish: Idioma purépecha para niños