Mexican War of Independence facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mexican War of Independence |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish American wars of independence | |||||||||

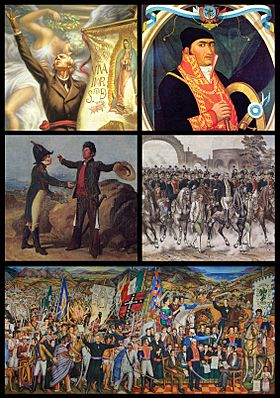

Clockwise from top left: Miguel Hidalgo, José María Morelos, Trigarante Army in Mexico City, Mural of independence by O'Gorman, Embrace of Acatempan between Iturbide and Guerrero |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

Mina |

|||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 600,000 killed | |||||||||

The Mexican War of Independence was a major conflict that led to Mexico becoming a free country, independent from the Spanish Empire. This war lasted from September 16, 1810, to September 27, 1821. It involved many local and regional struggles. The war ended when Mexico officially declared its independence in Mexico City on September 28, 1821. This happened after the Spanish government lost control and the independence fighters won.

Events in Spain directly caused the fight for independence to start in 1810. In 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Spain and put his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, on the Spanish throne. This made many people question who the real ruler was. In Spain and its colonies, people formed local councils. These councils claimed to rule in the name of the Spanish royal family. Representatives from Spain and its colonies met in Cádiz and wrote the Spanish Constitution of 1812. This new constitution aimed to create a new way of governing. It also tried to give more power to Spaniards born in America, called criollos. They wanted to be treated equally with Spaniards born in Spain, known as peninsulares. These political changes greatly affected Mexico. Differences in culture, religion, and race in Mexico also played a big role in how the independence movement grew.

The war happened in different stages. The first big uprising began on September 16, 1810. It was led by a priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, who gave a famous speech called the Cry of Dolores. Spanish forces captured Hidalgo and executed him in July 1811. The next part of the fight was led by another priest, José María Morelos. He was also captured and executed in 1815. After that, the fight turned into guerrilla warfare, with Vicente Guerrero becoming an important leader.

Neither side could win completely until 1821. That year, a former Spanish commander, Agustín de Iturbide, joined forces with Guerrero. They created an agreement called the Plan of Iguala. Together, they formed a strong army, the Army of the Three Guarantees. This army quickly led to the end of Spanish rule and the start of independent Mexico. The new unified army marched into Mexico City in September 1821. The Spanish viceroy, Juan O'Donojú, signed the Treaty of Córdoba, officially ending Spanish rule.

Indigenous people and Afro-Mexicans, like Vicente Guerrero and José María Morelos, played crucial roles in Mexico's fight for freedom. After independence, Mexico was first called the First Mexican Empire, led by Agustín de Iturbide. This monarchy didn't last long. In 1823, it was replaced by a federal republic. Spain finally recognized Mexico's independence in 1836.

Contents

The Spark of Independence

Miguel Hidalgo's Call to Action

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla is known as the father of Mexican independence. His uprising on September 16, 1810, started the war. He inspired thousands of ordinary men to follow him. Hidalgo was a learned priest. He was part of a secret group in Querétaro that planned an uprising. This group included Ignacio Allende, a captain in the Spanish army.

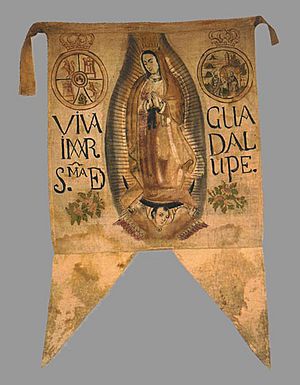

When Spanish officials discovered the plan, Hidalgo was warned. On September 16, 1810, Hidalgo gave his famous speech, the Grito de Dolores. He called for people to fight against bad government. Many people joined his revolt, using farm tools as weapons. The number of followers grew quickly. The movement's religious character was clear. Hidalgo used a banner with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Hidalgo's forces marched through towns, gaining more followers. On September 28, they reached Guanajuato. Spanish forces were barricaded inside a public granary. The rebels attacked, and many people were killed.

Hidalgo's army won the Battle of Monte de las Cruces and surrounded Mexico City. However, Hidalgo decided to retreat. This is seen as a big mistake. He might have wanted to spare the city from destruction. Hidalgo moved to Guadalajara. There was a period of intense violence against Spanish civilians. Spanish forces, led by Félix María Calleja del Rey, defeated Hidalgo's army. The rebels fled north but were captured in Coahuila.

Hidalgo was removed from his priesthood and executed on July 30, 1811. The heads of Hidalgo and other leaders were displayed as a warning in Guanajuato. This ended the first phase of the uprising.

Morelos Continues the Fight

José María Morelos Organizes the Movement

After Hidalgo's execution, the fight continued in southern regions. New leaders emerged, including priests José María Morelos and Mariano Matamoros, as well as Vicente Guerrero. These leaders organized their forces better and used guerrilla tactics. They also created documents explaining their goals.

Morelos was different from Hidalgo. He was of mixed-race background and understood racial discrimination. Morelos built an organized and disciplined army. He achieved military successes, capturing the port of Acapulco and other towns. Spanish forces then besieged Morelos at Cuautla for 72 days. Morelos's troops bravely held out and broke through the siege.

Morelos became the supreme military commander. In 1813, he called the Congress of Chilpancingo. This congress brought together representatives of the independence movement. Morelos presented his "Sentiments of the Nation" to the congress. In this document, he clearly stated that "America is free and independent of Spain."

On November 6, the Congress signed the first official declaration of independence. It called for Catholicism to be the only religion. It also demanded the end of slavery and racial distinctions, stating that "all shall be equal." This was very important for people of mixed race. Morelos also wanted equality before the law for everyone.

Morelos was captured on November 5, 1815. He was tried and executed. With his death, large-scale battles ended, and guerrilla warfare continued.

The Final Push for Freedom

Guerrero and Iturbide Form an Alliance

After Morelos's execution, Vicente Guerrero became the most important leader. From 1815 to 1821, most of the fighting was done by small guerrilla groups in southern Mexico.

The war was a stalemate. Neither side could deliver a final blow. Rebels often used guerrilla tactics. Spanish forces became discouraged. Spain sent few reinforcements.

In December 1820, Viceroy Juan Ruiz de Apodaca sent a Spanish Colonel, Agustín de Iturbide, to defeat Guerrero's army. Iturbide was known for his strong actions against earlier rebels. However, he was also unhappy with his lack of promotion.

Iturbide's mission happened at the same time as a military coup in Spain. The coup leaders forced King Ferdinand VII to bring back the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812. When this news reached Mexico, Iturbide saw it as a chance for powerful Mexicans to take control.

Guerrero realized that powerful Mexicans might declare independence without including the rebels. So, he decided to work with the Spanish army. Iturbide contacted Guerrero in January 1821. Guerrero was open to Iturbide's ideas. Equality for all races was very important to Guerrero. Iturbide accepted this change.

The two leaders negotiated how their forces would combine. Iturbide wrote the Plan of Iguala, proclaimed on February 24, 1821. This plan outlined three main goals for Mexico's independence:

- Mexico would be an independent monarchy.

- Spaniards born in America would have equal rights to Spaniards born in Spain.

- The Roman Catholic Church in Mexico would keep its special position.

The plan stated, "All inhabitants of New Spain, without distinction to their being Europeans, Africans, or Indians, are citizens of this Monarchy." Iturbide convinced Guerrero to join his movement. They formed the Army of the Three Guarantees to enforce the plan.

To symbolize the three guarantees (unity, religion, independence), Iturbide created a green, white, and red flag. These are still the colors of the modern Mexican flag.

Mexico's First Empire and Beyond

Independence Achieved

Iturbide convinced many Spanish officers to join the independence cause. Many soldiers left the Spanish army and joined Iturbide's forces. The Spanish military leaders in Mexico City removed the viceroy in July 1821.

By the time Juan O'Donojú became the new viceroy, most of the country supported the Plan of Iguala. The Spanish cause was lost. On August 24, 1821, Viceroy O'Donojú and Iturbide signed the Treaty of Córdoba. This treaty recognized Mexican independence under the Plan of Iguala.

Iturbide and the Army of Three Guarantees marched into Mexico City in triumph on September 27, 1821. The next day, Mexico's independence was officially declared. The Plan of Iguala and the Treaty of Córdoba quickly brought together rebels and former Spanish loyalists. This led to independence with little further fighting.

On September 27, 1821, the Army of the Three Guarantees entered Mexico City. The next day, Iturbide declared the independence of the First Mexican Empire. The Spanish government did not approve the Treaty of Córdoba. Iturbide included a special clause in the treaty. It allowed a Mexican congress to choose a Mexican monarch if no European prince accepted the crown.

On May 18, 1822, a large group of people demanded that Iturbide become emperor. The next day, the Congress declared Iturbide Emperor of Mexico. However, his rule was short-lived. On October 31, 1822, Iturbide dissolved Congress.

Spain's Attempts to Regain Control

Spain still controlled San Juan de Ulúa, a fortress near the port of Veracruz, until November 23, 1825. Spain tried to take Mexico back, especially in 1829 during the Battle of Tampico. A Spanish invasion force was surrounded and forced to surrender.

Finally, on December 28, 1836, Spain officially recognized Mexico's independence. This happened with the signing of the Santa María–Calatrava Treaty in Madrid. Mexico was the first former Spanish colony whose independence Spain recognized.

Celebrating Independence

In 1910, Mexico celebrated 100 years since Hidalgo's revolt. President Porfirio Díaz opened the Angel of Independence monument in Mexico City. This monument helps remember Mexico's freedom from Spain.

Even though Mexico became independent in September 1821, celebrating this event took time. The date was tricky because Agustín de Iturbide, who achieved independence, quickly became Emperor. His rule was short (1821-1823) and ended when the military forced him to step down.

After Iturbide was removed, people wanted to celebrate independence. A committee organized celebrations for both September 16th (Hidalgo's call to arms) and September 27th (actual political independence).

During the Díaz era (1876-1911), President Díaz's birthday was close to the September 15/16 celebration. The biggest celebrations happened in Mexico City's main square, the zócalo. In 1896, the bell that Hidalgo rang in 1810 was brought to the capital. It was renamed the "Bell of Independence" and is now rung every year as part of the Independence Day festivities.

In 2021, Mexico celebrated the 200th anniversary of the "Consummation of Independence."

Timeline

This timeline focuses on the exciting and challenging early years of the war, from 1810 to 1812, showing how the fight began and the first big steps toward freedom.

1799: The Conspiracy of the Machetes

- November 10: A group of 13 young men in Mexico City, led by Pedro de la Portilla, were arrested. They had a secret plan to try and take over the government palace. They didn't have many fancy weapons – just two guns and about 100 machetes (a type of large knife) and sabers. That's why it was called the "Conspiracy of the Machetes"!

Why it mattered: This event showed that even humble people were unhappy with Spanish rule and wanted change. It was an early sign of the desire for independence.

1808: Trouble in Spain and Mexico

- June 6: Far away in Europe, a powerful French leader named Napoleon Bonaparte took over Spain and made his brother, Joseph, the new king. This caused a big war in Spain! With Spain in chaos, people in its colonies, like Mexico, started to wonder: "If Spain's king isn't really in charge, who should we listen to?"

- August 25: A smart priest named Melchor de Talamantes wrote a paper saying that a colony could become independent if its home country was taken over by another power (like Spain was by France) and if the people wanted freedom.

- September 16: The Viceroy (Spain's top official in Mexico), José de Iturrigaray, was removed from his job by the Peninsulares. They thought he was too friendly with the Criollos, showing how much tension there was between the two groups.

1809: The Valladolid Conspiracy

- December 21: Mexican authorities discovered another secret plan, this time in a city called Valladolid (today it's Morelia). A group of military officers, led by José Mariano Michelena, wanted to set up a new government in Mexico City. They said they would rule in the name of the old Spanish king, Ferdinand VII, but they really wanted to stop France from having any influence in Mexico.

Why it mattered: This was another Criollo movement that showed they wanted more control, even if they weren't yet openly calling for full independence from Spain.

1810

- September 9: The government heard whispers of a new secret plan, the "Queretaro Conspiracy." This group wanted to overthrow the rule of the Peninsulares and replace them with Criollos. They were worried the Peninsulares might hand Mexico over to the French.

Key Leaders: This conspiracy included important people like military officers Ignacio Allende and Juan Aldama, a Roman Catholic priest named Miguel Hidalgo, and the Mayor of Queretaro, Miguel Dominguez, and his brave wife, Josefa Ortiz de Dominguez (known as "la Corregidora").

Hidalgo Takes Charge: Miguel Hidalgo was chosen as the leader because he was good at inspiring people, especially the Mestizos and Indigenous people in the region. They planned to start their uprising on October 2.

- September 15: A Warning! La Corregidora found out the government was arresting conspirators! She quickly sent messengers to warn Hidalgo and Allende in the town of Dolores.

- September 16: At 2 a.m., Hidalgo and Allende learned the plan was discovered. They decided they couldn't wait!

Early that morning, Hidalgo rang the church bells, gathered his followers, and gave a powerful speech, known as the "Grito de Dolores" (Cry of Dolores). This speech officially started the Mexican War of Independence! Hidalgo and his followers, about 500 to 800 men, took over Dolores and began marching south. They carried a banner with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, who became a powerful symbol for their cause.

- September 28: The Battle of Guanajuato: Hidalgo's army grew to 25,000 men, pri'marily Indigenous people and Mestizos. They captured Guanajuato City, storming a fortified granary. During the attack, many people lost their lives and the city was looted.

- October 25: Morelos Joins the Fight: Another important priest, José María Morelos, a Mestizo, started his own military campaign in the state of Guerrero. He began with only 25 men but quickly grew his army. Unlike Hidalgo, Morelos focused on training his soldiers and keeping strict discipline.

- October 30: Marching on Mexico City: Hidalgo's army, now 60,000 to 80,000 strong, marched towards Mexico City. They won a battle at Monte de las Cruces. But then, Hidalgo made a surprising decision and ordered a retreat, even though they were close to the capital.

- November 7: Hidalgo's army, now smaller, was defeated by a royalist army at Aculco.

- November 26: Guadalajara Captured: Hidalgo and 7,000 followers entered Guadalajara, Mexico's second-largest city, in triumph. In Guadalajara, Hidalgo openly declared that the goal was complete independence for Mexico, no longer pretending to support the old Spanish king.

- December 12: Hidalgo ordered the execution of at least 350 Spanish-born Peninsulares in Guadalajara, suspecting a plot against him. This was a very difficult time, and even Allende considered stopping Hidalgo.

1811

- January 17: Battle of Calderon Bridge: A large royalist army, well-trained and equipped, defeated Hidalgo's huge but disorganized army of up to 100,000 men. This was a major setback for the insurgents.

- January 24-25: Hidalgo Loses Command: After the defeat, the insurgent leaders met. Hidalgo was secretly removed from his command, and Allende took over, though Hidalgo remained a figurehead.

- March 21: Leaders Captured: While trying to retreat north towards the United States for support, Allende, Hidalgo, and other leaders were tricked and captured at the Wells of Baján by a royalist who pretended to be on their side.

- June 26 & July 30: Executions: Ignacio Allende, Jose Mariano Jimenez, Juan Aldama, and Miguel Hidalgo were all executed in Chihuahua City. The heads of Hidalgo and other insurgent leaders were taken to Guanajuato and displayed as a warning.

- August 15: Morelos's Success: Meanwhile, José María Morelos had been very successful in his "First Campaign," capturing several cities and controlling much of Mexico's southern Pacific coast.

- August 19: A New Government: Ignacio López Rayón, who had been left behind, became the new leader of the independence movement. He formed a revolutionary government called the "Junta of Zitacuaro" in a safe town. Morelos was part of this new government.

- November 15: Morelos's Second Campaign: Morelos began a new campaign to help the Junta and threaten important cities like Mexico City.

The Fight Continues: 1812

- January 2-5: Zitacuaro Attacked: Royalist troops attacked Zitacuaro, Rayón's stronghold. The city was conquered and burned to the ground. Rayón managed to escape.

- February 19: The Siege of Cuautla: Morelos and his 4,000 soldiers bravely defended the town of Cuautla against a much larger royalist army.

- April 30: A Constitution for Mexico: Rayón sent Morelos a draft of a new constitution. It still mentioned the Spanish king but called for full independence, the end of slavery, the end of the unfair caste system, and freedom of the press! These were very important ideas for a new, free Mexico.

- May 2: Escape from Cuautla: After a long siege, Morelos and his army bravely fought their way out of Cuautla. Many people were lost, but Morelos and part of his army escaped to continue the fight.

This timeline shows just the beginning of Mexico's long and brave fight for independence. Even with many challenges and losses, the dream of a free Mexico continued to burn brightly, carried forward by new heroes like José María Morelos!

Images for kids

-

This painting by Cristóbal de Villalpando from 1695 shows the damage to the viceroy's palace after the 1692 riot.

See also

In Spanish: Independencia de México para niños

In Spanish: Independencia de México para niños

- Afro-Mexicans in the Mexican War of Independence

- List of wars involving Mexico

- Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico

- Timeline of Mexican War of Independence

- Mexico

- First Mexican Empire

- Spanish American wars of independence

- New Spain

- Cry of Dolores

- Our Lady of Sorrows

- History of Spain (1808–1874)

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |