Porfiriato facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

United Mexican States

Estados Unidos Mexicanos

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1876–1911 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Government | Federal presidential republic under a personalist dictatorship | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1876

|

Porfirio Díaz | ||||||||

|

• 1876–1877

|

Juan Méndez | ||||||||

|

• 1877–1880

|

Porfirio Díaz | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

10 January 1876 | ||||||||

|

• Mexican Revolution begins

|

20 November 1910 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

25 May 1911 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

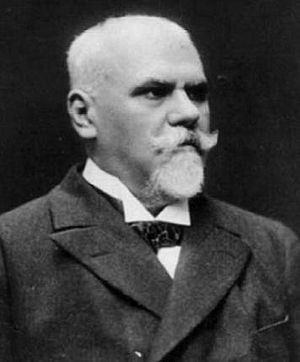

The Porfiriato was a time in Mexican history when General Porfirio Díaz ruled as president. This period lasted from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. Díaz first took power in 1876 through a military takeover. He aimed for "order and progress" in Mexico. This meant inviting foreign businesses to invest and keeping peace, sometimes by force.

During the Porfiriato, Mexico saw big changes in its economy, technology, society, and culture. Díaz was elected president many times, ruling almost continuously from 1884. As he neared his 80th birthday in 1910, he had no clear plan for who would take over. The elections in 1910 were seen as unfair. This led to violence, forcing Díaz to step down and leave the country. Mexico then faced a long civil war known as the Mexican Revolution.

Contents

- Understanding the Porfiriato Era

- How Political Order Was Maintained

- Economic Growth and Industry

- Labor and Social Changes

- Social Classes and Roles

- Education and Public Health

- Culture and Modernity

- Religion and the Church

- Historical Memory and Centennial Celebrations

- The End of the Porfiriato

- See also

- Images for kids

Understanding the Porfiriato Era

Historians study the Porfiriato as a special time in Mexico's past. It was a period of big political changes. This era is often seen as different from the Mexican Revolution that followed. Yet, many believe the Porfiriato set the stage for modern Mexico.

Under Díaz, Mexico became more stable and organized. The government gained more power. It also welcomed foreign investments, which changed the economy. This led to quick growth in technology and culture. Cities grew, and the way rich people lived changed. However, the benefits of this growth were not shared equally. Many poor people, especially farmers, faced hardship.

Porfirio Díaz's Rise to Power

Díaz was a liberal general who fought bravely in earlier wars. He wanted to be president of Mexico. He achieved this by leading a rebellion against President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada. This rebellion was called the Plan of Tuxtepec. Díaz first ruled from 1876 to 1880. During this time, he made his power strong and got the U.S. government to recognize his rule.

The Plan of Tuxtepec said that a president could not be re-elected. So, after his first term, Díaz's friend, General Manuel González, became president for one term. But in 1884, Díaz ignored this rule and returned to power. He stayed president until 1911. In 1910, Francisco I. Madero challenged Díaz. Madero's slogan was "Effective suffrage, no reelection."

How Political Order Was Maintained

After 1884, Díaz's rule became very strong, like a dictatorship. No one who opposed him was elected to Congress. Díaz stayed in office through elections that were not truly democratic. Congress simply approved his laws. This period of peace was sometimes called the Pax Porfiriana. It was possible because the Mexican government grew stronger. It also had more money from a growing economy.

Díaz replaced local leaders with people loyal to him. He also calmed unhappy people by giving them jobs working with foreign investors. This allowed these people to become rich. To make the government even stronger, Díaz appointed jefes políticos (political bosses). These bosses answered directly to the central government and controlled local forces.

Díaz used a policy of "bread or bludgeon" (pan o palo). This meant he would offer rewards or use force to keep order. This allowed him to appoint state governors who could do what they wanted locally. As long as they did not interfere with Díaz's plans. This system caused problems for native communities. Their lands were often taken for large estates, called haciendas. These estates were often owned by foreign investors. Peasants who could not read or write found it hard to fight back.

Border Issues and U.S. Relations

When Díaz became president in 1876, the border with the U.S. was a problem area. Native groups and cattle thieves caused trouble. The Apache people did not see the U.S. or Mexico as rulers of their land. They used the border to their advantage, raiding on one side and hiding on the other. Thieves also used the border to escape.

The U.S. used these border issues to avoid recognizing Díaz's government. This led to small conflicts. The problem was solved when Díaz gave good deals to U.S. investors in Mexico. These investors then pushed U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes to recognize Díaz in 1878. Díaz clearly showed that keeping order was his top priority.

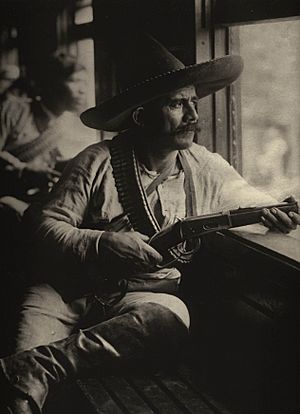

The Rurales and Railways

After years of war, Mexico had a problem with banditry. To fight this, President Benito Juárez created a small police force called the Rurales. When Díaz became president, he made the Rurales much bigger. They were directly under his control, unlike the regular army.

The slogan of the Porfiriato was "order and progress." This meant that without political order, the economy could not grow. Investors would not risk their money if the country was unstable.

Building railways helped the government control more parts of Mexico. Before, many regions were hard to reach. Railway lines also had telegraph lines next to them. This meant orders from Mexico City could reach officials far away instantly. The government could quickly send armed Rurales on trains to stop any unrest. By the late 1800s, violence had almost disappeared.

Economic Growth and Industry

At the start of the Porfiriato, Mexico was mostly a farming nation. Large landowners controlled most of the crops. Many Mexicans were small farmers or landless peasants. Land ownership was changing. Earlier laws had tried to break up large church and native community lands. This did not create many small farmers. Instead, it weakened native communities. Their lands were often taken and given to Díaz's allies.

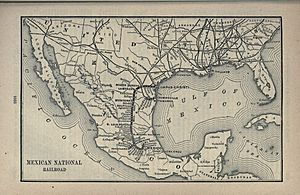

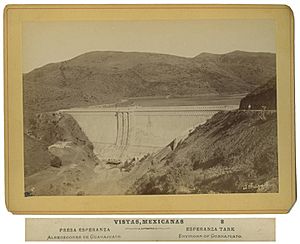

Railways and Communication

Building railways was a huge step for Mexico's economy. Mexico did not have many rivers for cheap transport. Roads were often bad. Railways solved this problem. The first line went from Veracruz to Mexico City. Then, many more lines were built in central Mexico and up to the U.S. border. This made transport cheaper and opened new areas for farming.

Foreign companies provided the money, tracks, and trains for these railways. This showed that foreign investors trusted Mexico's stability. Railways also helped reduce banditry. The Rurales could be sent quickly to troubled areas.

Telegraph lines were built alongside the railway tracks. This allowed instant messages between the capital and distant cities. It gave the central government more power over far-off regions.

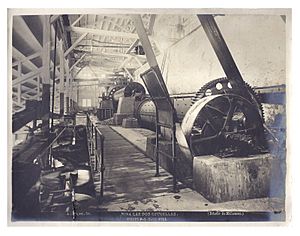

Mining and Manufacturing

Mining grew a lot during this time. In earlier times, Mexico mined silver. But this industry declined after independence. During the Porfiriato, mining of industrial minerals became important. The price of silver dropped, but developed countries needed minerals for their factories.

The government's stability helped the mining sector grow. The new railway network made it cheap to transport ore. The telegraph network allowed quick communication for investors. Foreign investors, especially from the U.S., put their money into Mexican mines. Mines for copper, lead, iron, and coal grew in northern Mexico. Cities like Monterrey and Aguascalientes became important mining centers.

Industrial manufacturing also grew, mainly for textiles. Factories were built in cities like Orizaba and Guanajuato. These factories gave workers jobs and wages. Many were owned by French people. They used steam power, which was modern technology.

Labor and Social Changes

Before Díaz, workers had groups to help each other. These groups, like the Gran Círculo de Obreros de México, wanted benefits for sick or injured workers. In 1875, the Congreso Obrero pushed for adult education and required schooling for children. The labor movement was not always united.

As Mexico's economy grew after 1900, industrial labor unions also grew. Workers sometimes resisted new machines in factories. Strikes happened in textile mills, with the Río Blanco strike being well-known. Railway workers were the most organized, with about half of them in unions. However, U.S. workers often held the higher-skilled jobs and were paid more than Mexicans for the same work.

Mine workers also formed unions. The Cananea Strike in 1906 is famous. It happened at a U.S.-owned mine, and armed men from Arizona came to stop the strike. Many workers wanted reforms, not a revolution. But when Díaz's government did not respond, many workers wanted a change in leadership.

Women in the Workforce

Urban women found new jobs in government and private companies. While staying home was a sign of middle-class status, more women started working outside the home. In the mid-1800s, women began working as public school teachers and in charity.

The Díaz government opened jobs for women as office workers in the 1890s. As government paperwork increased, educated women were hired. They used new office tools like typewriters, telephones, and telegraphs. Women also worked in factories making paper, textiles, chocolate, shoes, and hats.

Social Classes and Roles

The wealth from farming and industry mostly helped rich people in cities and foreigners. The gap between the rich and the poor grew wider. Most Mexicans lived in rural areas and were native people. Cities, especially the capital, had the most wealthy elites.

Peasant men worked land owned by others. Peasant women raised children, cooked, and cleaned. In cities, poor women worked as servants or in factories. Poor men did many kinds of manual labor. In central and southern Mexico, native communities lost land and political power.

The government wanted to create citizens who followed civic values. This was done through better public health, military training for men, and public education. The state tried to replace old values based on religion with new ones shared by all citizens.

Middle Class and Women's Rights

The Porfiriato saw the growth of the urban middle class. More women became teachers and office workers. These new roles added to family income. They also helped shape the identity of middle-class homes. Some women became active in fighting for women's rights.

Middle-class Mexican women began to speak out against unfairness. Feminism in Mexico started during this time. Women formed groups, started magazines, and attended international meetings on women's rights. While some pushed for women to vote, this did not happen until 1953.

Education and Public Health

Liberals created a public education system to reduce the influence of the Catholic Church. Public schools grew during the Porfiriato. Schools taught reading, writing, and math. They also aimed to teach students good work habits like being on time and saving money. They also taught against drinking and gambling.

Despite these efforts, many people could not read. In 1910, only about 33% of men and 27% of women could read. However, the government's focus on education was important. Especially in higher education, with the creation of the National University of Mexico. Teaching was one of the few respected jobs open to women. Educated women teachers were leaders in the feminist movement in Mexico.

Improving Public Health

Public health became important for the Mexican government. They believed a healthy population was key for economic growth. The government invested in big projects to modernize public health. In Mexico City, they worked to drain the central lake system to stop floods. Canals in the city were used for sewage and trash.

Access to clean water was also a problem. People often got water from public fountains. Workers would carry it to homes. Some families were too poor to pay for this service. Planners saw these problems as solvable with science. They also worked on improving cleanliness in meatpacking. Teaching good hygiene was also a goal in schools.

Culture and Modernity

During the Porfiriato, rich Mexicans in cities became more interested in foreign styles. They bought imported clothes and goods, seeing it as a sign of Mexico's progress. France was especially admired for its sophistication. After the French invasion of Mexico ended in 1870, relations improved. Mexico eagerly adopted French styles. Department stores like the Palacio de Hierro were built like those in Paris and London. French influence was seen in fashion, art, and buildings in major Mexican cities.

Sports and Entertainment

Horse racing became popular among the rich. New race tracks were built, like the Hippodrome of Peralvillo. The Jockey Club was founded in 1881, like clubs in Europe. It was a place for elite social gatherings. Even President Díaz and his advisors were members. The club had rooms for smoking, dining, and games. Gambling houses were also popular and regulated by the government. For common people, traditional sports like cockfighting and bullfighting were popular.

Bicycles came to Mexico City from Paris and Boston in 1869. A French company started a bike rental business. The sport grew when bikes improved in the 1890s. Bicycle clubs and races started. Organized sports with rules became a sign of modernity. Women also rode bikes, which challenged old ideas about how women should behave and dress. Riding a bike required different clothes, and many women wore Bloomers. Cycling was seen as promoting exercise and good health. It was linked to modern technology and speed.

Religion and the Church

The mid-1800s saw conflict between the Catholic Church and the liberal government. The Mexican Constitution of 1857 separated church and state. It had strong rules against the Church. Díaz was a practical leader and did not want to restart this conflict. His marriage to Carmen Romero Rubio, a strong Catholic, helped heal the divide.

Díaz never removed the anti-Church rules from the constitution. But he did not strictly enforce them. This allowed the Catholic Church to regain some power and wealth during the Porfiriato. U.S. Protestant missionaries also came to Mexico, especially in the north. However, they did not greatly challenge the power of Catholicism.

The Pope Leo XIII issued a letter called Rerum Novarum. It asked the Church to get involved in social problems. In Mexico, some Catholics supported ending debt peonage. This was a system where peasants were tied to working on estates because they owed money. The Church itself had lost land earlier, so it could support the peasants.

Historical Memory and Centennial Celebrations

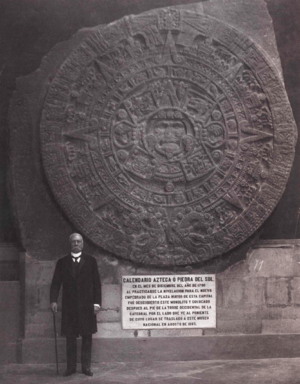

During Díaz's rule, the government began to control Mexico's historical treasures. The National Museum of Anthropology was expanded. It became the main place for artifacts from Mexico's ancient sites. The government also took control of the sites themselves. The Law of Monuments (1897) gave the federal government power over archaeological sites. This led to farmers being moved from sites like Teotihuacan.

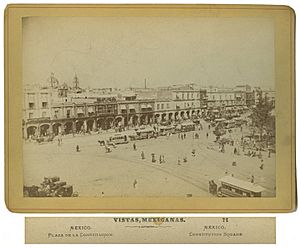

A wide, tree-lined street called Paseo de la Reforma was built. It was decorated with statues honoring important figures and events in Mexican history.

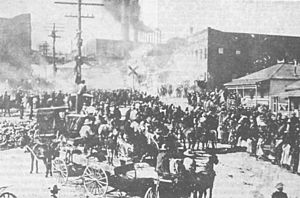

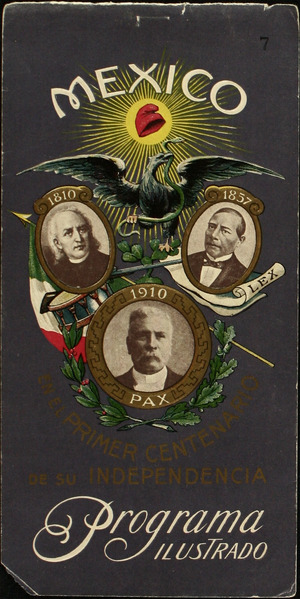

Mexico's 1910 Centennial

The official celebrations for Mexico's 100th year of independence happened in September 1910. Mexico City was decorated with lights and flowers. A book was published detailing the events. These included opening new buildings and statues, parties for important guests, military parades, and historical processions.

The main celebrations were on September 15, Díaz's 80th birthday, and September 16. September 16 was the 100th anniversary of Hidalgo's Grito de Dolores. This event started Mexico's fight for independence in 1810. On September 15, there was a huge parade showing Mexican history. It focused on the conquest, independence, and liberal reforms. Díaz stood on the balcony of the National Palace at 11 p.m. He rang the bell from Father Hidalgo's church and shouted "Viva Mexico!" On September 16, Díaz opened the Monument to Independence. About 10,000 Mexican troops and foreign soldiers marched there.

Díaz also opened the monument to Benito Juárez on September 18. Juárez was a political rival, but Díaz honored his contributions. The French ambassador returned the keys to Mexico City that were taken during the French Intervention. Many nations took part in the celebrations, including Japan. Díaz also opened a new building for the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA).

The Spanish monarchy sent a special ambassador. Díaz held a huge party for him. Díaz also laid the first stone for a monument to Isabel the Catholic. He opened an exhibition of Spanish colonial art. The Spanish ambassador returned historical items to Mexico. These included Father Morelos's uniform and other independence relics. The King of Spain gave Díaz the highest honor, the Order of Charles III.

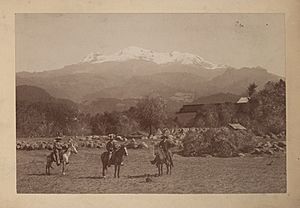

The International Congress of Americanists met in Mexico City. Díaz was made its honorary president. Famous scholars from many countries attended. Díaz and his education minister, Justo Sierra, visited the ancient site of Teotihuacan with the attendees.

On September 8, there was a tribute to the Niños Héroes. These were young cadets who died defending Chapultepec Castle during the Mexican–American War. Díaz also laid the first stone for a monument to George Washington in Mexico City. Many U.S. journalists attended the celebrations. Statues honoring France's Louis Pasteur and Germany's Alexander von Humboldt were also opened.

The End of the Porfiriato

The 1910 centennial celebrations were the last big moments for Díaz's rule. Francisco I. Madero, who challenged Díaz for president, was jailed during the 1910 elections. But he escaped to Texas in the U.S. From there, he issued the Plan of San Luis Potosí in October 1910. This plan said the election was unfair and called for a rebellion against Díaz.

Fighting broke out in Morelos and near the U.S. border in Ciudad Juárez. The Mexican army could not stop these uprisings. More people opposed Díaz because his government could not restore order. Díaz had also failed to plan for who would take over after him. His political rivals, General Bernardo Reyes and Finance Minister José Yves Limantour, were not chosen. Díaz picked Ramón Corral as his vice president. Reyes went into exile in Europe. Limantour was also in Europe, dealing with Mexico's debt. This left Díaz feeling more alone politically.

Díaz tried to negotiate with Madero's uncle, promising changes if peace returned. He also talked with rebels in early 1911. But Díaz refused to resign. This made the rebellion stronger, especially in Chihuahua, led by Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa. Facing this, Díaz agreed to the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez. This treaty said Díaz and Vice President Corral had to resign. It created a temporary government under Francisco León de la Barra until new elections. The rebel forces were supposed to disarm.

Díaz and most of his family sailed to France, where he lived in exile. He died in Paris in 1915. As he left Mexico, he reportedly said, "Madero has released a tiger, let us see if he can control it."

See also

In Spanish: Porfiriato para niños

In Spanish: Porfiriato para niños

- El hijo del Ahuizote

- Cananea strike

- Río Blanco strike

- John Kenneth Turner

- Plan of Tuxtepec

- Porfirio Díaz

- Científicos

- Economic history of Mexico

- History of democracy in Mexico

Images for kids

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |